Validating Phage Ecogenomic Signals in Metagenomes: A Guide for Robust Detection and Analysis

The accurate identification and validation of bacteriophage sequences within whole-community metagenomes is a critical, yet challenging, step in understanding viral ecology, phage-host dynamics, and their implications for human health and...

Validating Phage Ecogenomic Signals in Metagenomes: A Guide for Robust Detection and Analysis

Abstract

The accurate identification and validation of bacteriophage sequences within whole-community metagenomes is a critical, yet challenging, step in understanding viral ecology, phage-host dynamics, and their implications for human health and biotechnology. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing the entire workflow from foundational concepts to advanced validation. We explore the expanding diversity of phages, including jumbo phages, revealed by metagenomic surveys. The guide critically assesses current computational tools, from homology-based to machine learning approaches, and outlines best practices for benchmarking their performance. Furthermore, we detail strategies for in silico and experimental validation of phage signals, including host assignment and the use of viromes as validation standards. This synthesis aims to empower robust and reproducible phage ecogenomics, facilitating the translation of metagenomic signals into biological insights and therapeutic opportunities.

Unveiling the Viral Dark Matter: Foundations of Phage Diversity and Metagenomic Signals

Bacteriophages, or phages, are the most abundant and diverse biological entities on Earth. They play a pivotal role in shaping microbial communities through predation, horizontal gene transfer, and modulation of host metabolism. Recent advances in metagenomic sequencing have unveiled an unprecedented diversity of phage genomes, revealing expansive viral "dark matter" that had previously eluded characterization. Within this diversity, two groups stand out as particularly significant: jumbo phages with large genomic repertoires that blur the boundaries between viruses and cellular life, and crAss-like phages that dominate the human gut virome. Understanding the genomic landscape of these phages is critical for elucidating their ecological functions and potential applications in medicine and biotechnology. This review synthesizes current knowledge on phage genomic diversity, with a specific focus on validating phage ecogenomic signals within complex whole-community metagenomes—a fundamental challenge in viral ecology.

The Expanding Universe of Phage Genomic Diversity

Global Cataloguing Efforts and Quantitative Diversity

Large-scale metagenomic studies have dramatically expanded our catalog of phage genomes. The construction of unified, high-quality genome resources from diverse habitats has enabled systematic ecological and evolutionary insights previously hampered by fragmented data with significant habitat-specific biases [1]. One such effort analyzed 59,652,008 putative viral sequences from multiple environments to create a curated database of 741,692 phage genomes with ≥50% completeness (PGD50) [1]. This resource revealed that 28.96% (214,814) of these phage genomes clustered into 158,522 species-level viral clusters without any representation in existing databases, highlighting the substantial novelty being uncovered [1].

Table 1: Phage Diversity Across Different Habitats and Host Systems

| Habitat/Host System | Number of vOTUs/vMAGs | Notable Phage Groups | Key Genomic Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gut | 3738 complete genomes (451 genera) | "Flandersviridae", "Quimbyviridae", "Gratiaviridae" | Catalases, iron-sequestering enzymes, DGRs, isoprenoid pathway enzymes | [2] |

| Pig Gut | 12,896 high-confidence vOTUs | crAss-like phages (533 vOTUs) | Anti-CRISPR genes, CAZymes (lysozymes), alternative genetic codes | [3] [4] |

| Mouse Gut | 977 high-confidence vOTUs | Novel clades with high prevalence | Cas-harboring jumbophages | [3] |

| Cynomolgus Macaque Gut | 1,480 high-confidence vOTUs | crAss-like phages | 55.88% have connections to human microbiota | [3] |

| Honey Bee Gut (Individual Bees) | 1,069 vOTUs from 49 bees | Modular phage-bacteria interaction networks | High strain-level diversity correlated with bacterial hosts | [5] |

| Oral Cavity | 189,859 representative sequences | 3,416 huge phages (>200 kbp) | Anti-defense genes, AMGs, virulence factors | [6] |

| Human Breast Milk | 7 primary phage families | Herelleviridae, Myoviridae, Podoviridae | Vertical mother-to-infant transmission | [7] |

The honey bee gut microbiome has emerged as a powerful model system for studying phage-bacteria interactions due to its relative simplicity and well-characterized bacterial community. Research on 49 individual bees revealed 1,069 viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs) with a highly modular phage-bacteria interaction network structure, where viral and bacterial diversity were strongly correlated, particularly at the strain level [5]. This correlation underscores the importance of strain-level resolution when studying phage-bacteria diversity patterns, as phage specificity often occurs at this taxonomic level rather than at the species level [5].

Jumbo Phages: Genomic Giants with Expanded Capabilities

Jumbo phages, typically defined by genomes exceeding 200 kbp, represent a fascinating frontier in phage genomics. These genomic giants encode expanded functional repertoires that may include metabolic genes, defense systems, and transcriptional machinery typically associated with cellular organisms. A comprehensive analysis of oral phages identified 3,416 "huge phages" with genome sizes >200 kbp, demonstrating their presence in diverse body sites [6].

Particularly noteworthy are cas-harboring jumbophages discovered in mammalian guts, which encode CRISPR-Cas systems potentially used in competition with other mobile genetic elements or host defenses [3]. These findings challenge traditional views of phages as simple genetic parasites and suggest more complex evolutionary relationships with their bacterial hosts.

Jumbo phages often manipulate host metabolism in sophisticated ways. Some "Flandersviridae" phages, for instance, encode enzymes of the isoprenoid pathway, a lipid biosynthesis pathway not previously known to be manipulated by phages [2]. Similarly, numerous phages across different families encode catalases and iron-sequestering enzymes that may enhance cellular tolerance to reactive oxygen species, potentially providing protection to their bacterial hosts under oxidative stress [2].

CrAss-like Phages: Ubiquitous Colonizers of the Mammalian Gut

Since its discovery in 2014, the crAss-like phage family has emerged as one of the most abundant and widespread viral groups in the human gut. Recent research has expanded our understanding of their diversity, host interactions, and distribution across mammalian species.

In pig guts, crAss-like phages are distributed across four well-known family-level clusters (Alpha, Beta, Zeta, and Delta) but are notably absent from Gamma and Epsilon clusters [4]. Genomic analysis of 533 pig crAss-like phage vOTUs revealed that 149 utilize alternative genetic codes, while approximately 64.73% of their genes lack functional annotations, highlighting significant gaps in understanding their functional potential [4].

These phages primarily infect bacteria in the Bacteroidetes phylum, particularly Prevotella, Parabacteroides, and UBA4372 [4]. Interestingly, interactions between crAss-like phages and Prevotella copri may influence fat deposition in pigs, suggesting potential applications in agricultural science [4]. Unlike the high prevalence observed in human populations, pig crAss-like vOTUs generally exhibit low prevalence across populations, indicating greater heterogeneity in their compositions [4].

Table 2: Comparative Genomic Features of crAss-like Phages Across Mammals

| Feature | Human Gut | Pig Gut | Cynomolgus Macaque Gut |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Distribution | All known clusters | Alpha, Beta, Zeta, Delta (no Gamma, Epsilon) | Similar to human with animal-specific characteristics |

| Genome Size Range | ~70-100 kbp | >70 kbp | Similar to human |

| Host Range | Primarily Bacteroidetes | Prevotella, Parabacteroides, UBA4372 | Primarily Bacteroidetes |

| Prevalence | High, ubiquitous | Low prevalence, heterogeneous | 55.88% connected to human microbiota |

| Unique Features | Carrier state lifestyle | Alternative genetic codes, anti-CRISPR proteins, CAZymes | Animal-specific clusters |

Methodological Framework: Validating Ecogenomic Signals in Metagenomes

Experimental Workflows for Phage Genome Recovery

The accurate identification and characterization of phage genomes from metagenomic data requires sophisticated computational workflows that integrate multiple complementary approaches. The standard pipeline involves sequential steps of quality control, assembly, viral sequence identification, quality filtering, and host assignment [3] [8].

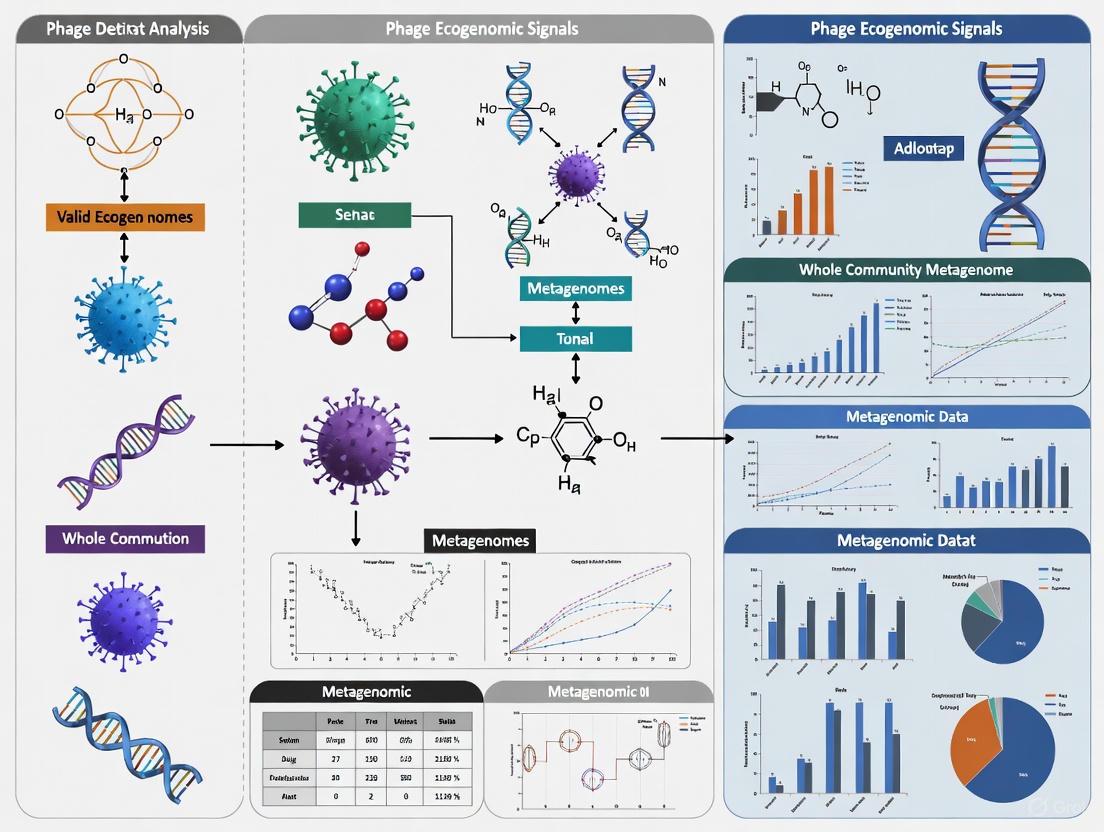

Figure 1: Workflow for phage genome recovery from metagenomic data. Critical steps include quality assessment tools like CheckV for estimating completeness and removing contaminating host sequences, followed by multiple viral identification tools to maximize recovery of diverse phage types.

The recovery of high-quality viral genomes requires stringent quality control measures. As demonstrated in studies of mammalian gut viromes, contigs are typically filtered to retain only those with ≥90% completeness as assessed by CheckV, while removing those with potential contamination or questionable quality warnings [3]. For species-level clustering, 95% average nucleotide identity (ANI) and 85% alignment fraction (AF) across the shorter sequence are widely adopted standards [3] [5].

The Marker-MAGu pipeline represents an innovative approach for simultaneous profiling of phage and bacterial communities from whole-community metagenomes [9]. This method identifies essential phage genes (involved in virion structure, genome packaging, and replication) and integrates them with bacterial marker genes from MetaPhlAn, enabling trans-kingdom taxonomic profiling from the same metagenomic dataset [9]. When applied to 12,262 longitudinal samples from 887 children, this approach demonstrated that phage communities change more quickly than bacterial communities, with most phages persisting for shorter durations [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Phage Metagenomics

| Tool Name | Function | Key Features | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| VirSorter2 | Viral sequence identification | Modular outputs, detects diverse phage types | Metagenomic and single-genome data |

| DeepVirFinder | Viral sequence identification | k-mer based machine learning approach | Metagenomic data, novel phage detection |

| CheckV | Viral genome quality assessment | Estimates completeness, removes host contamination | Quality control for viral genomes |

| PhaMer | Viral sequence identification | Transformer model for metagenomic prediction | Handling fragmented metagenomic data |

| geNomad | Viral taxonomy & identification | Viral taxon markers for ICTV lineages | Taxonomic classification |

| BACPHLIP | Lifestyle prediction | Classifies virulent vs. temperate phages | Ecological inference |

| CRISPR spacer matching | Host prediction | Identifies protospacers matching bacterial CRISPR arrays | Host-phage interaction mapping |

| Marker-MAGu | Trans-kingdom profiling | Simultaneous detection of phages and bacteria | Whole-community metagenomic analysis |

Ecogenomic Signatures: Validating Phage-Habitat Associations

The concept of ecogenomic signatures refers to the habitat-specific genetic patterns that can distinguish microbial ecosystems. Research has demonstrated that individual phages can encode clear habitat-related signals diagnostic of underlying microbiomes [10]. For example, the gut-associated φB124-14 phage encodes an ecogenomic signature that can segregate metagenomes according to environmental origin and distinguish contaminated environmental metagenomes from uncontaminated datasets [10].

This approach was validated through comparative analysis of the relative representation of phage-encoded gene homologs in metagenomic datasets from different habitats. The φB124-14 phage showed significantly greater representation in human gut viromes compared to environmental datasets, while cyanophage SYN5 displayed the opposite pattern—greater representation in marine environments [10]. These distinct ecogenomic signatures persisted even when analyzing whole-community metagenomes, though the effects were less pronounced than in viral fraction metagenomes [10].

The power of ecogenomic signatures extends to clinical applications. In the TEDDY study, the addition of phage taxonomic profiles improved the ability to discriminate samples geographically over bacterial taxonomic profiles alone [9]. Furthermore, temporal dynamics of phage and bacterial communities differed during the second year of life for children later diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, suggesting that phage ecogenomic signatures may serve as early indicators of disease susceptibility [9].

The landscape of phage genomic diversity encompasses extraordinary variation, from the genomic giants represented by jumbo phages to the ubiquitous crAss-like phages that dominate mammalian guts. Methodological advances in metagenomic analysis have enabled the recovery of increasingly complete and accurate phage genomes, revealing novel taxa and unexpected genomic features. The validation of phage ecogenomic signatures in whole-community metagenomes represents a particularly promising frontier for both basic microbial ecology and applied biotechnology. As reference databases continue to expand and analytical methods improve, we anticipate that phage ecogenomic signatures will find increasing applications in source tracking, disease diagnostics, and therapeutic development. The integration of phage data with bacterial community profiles will provide a more complete understanding of microbiome dynamics and their impact on human and animal health.

The vast universe of bacteriophages (phages) represents one of the most significant frontiers in microbial ecology, yet it remains largely unexplored. Metagenomics has emerged as a powerful discovery engine, enabling researchers to probe this universe by identifying phage sequences within complex microbial communities without the need for cultivation [11]. A critical hypothesis driving this research is that individual phages encode discernible, habitat-associated ecogenomic signatures—genetic patterns diagnostic of their underlying microbial ecosystems [10]. For instance, the gut-associated phage ϕB124-14 encodes a specific suite of genes whose homologs are significantly enriched in human gut-derived metagenomes compared to those from other environments [10]. Validating these signals in whole community metagenomes is paramount, as it allows for the direct study of phage-host dynamics and integrated prophages, moving beyond the limitations of purified viromes [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern bioinformatic tools designed to detect these phage sequences, providing a framework for researchers to validate ecogenomic signals and expand the known phage universe.

The development of numerous computational tools for phage identification has created a need for systematic benchmarking. Independent studies have evaluated these tools on standardized datasets to assess their precision, recall, F1 scores, and robustness to various challenges [12] [13]. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of leading tools on a benchmark of artificial contigs derived from RefSeq genomes.

Table 1: Performance of Phage Identification Tools on RefSeq Artificial Contigs

| Tool | Primary Approach | Reported F1 Score | Reported Precision | Reported Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIBRANT | Gene-based / Machine Learning | 0.93 | — | — |

| VirSorter2 | Gene-based / Machine Learning | 0.93 | — | — |

| Kraken2 | k-mer-based / Reference Database | 0.86 (on Mock Community) | 0.96 (on Mock Community) | — |

| DeepVirFinder | k-mer-based / Machine Learning | — | — | — |

| VirFinder | k-mer-based / Machine Learning | — | — | — |

| Seeker | Sequence Composition / Machine Learning | — | — | — |

| PPR-Meta | Sequence Composition / Machine Learning | (High FPs on shuffled sequences) | — | — |

| MetaPhinder | Homology / Reference Database | — | — | — |

| viralVerify | Gene-based / Machine Learning | — | — | — |

The performance of these tools can vary significantly based on the benchmark. For example, Kraken2 achieved a notably high F1 score of 0.86 on a mock community benchmark, largely due to its exceptional precision of 0.96 [12] [11]. In contrast, some tools, most notably PPR-Meta, have been shown to call a high number of false positives on randomly shuffled sequences, indicating a potential lack of specificity [12] [11].

Generally, a trade-off exists between different methodological approaches. Homology-based tools (e.g., VirSorter, VIBRANT, VirSorter2, viralVerify) typically demonstrate low false positive rates and robustness to eukaryotic contamination [13]. Conversely, tools relying on sequence composition (e.g., VirFinder, DeepVirFinder, Seeker) often show higher sensitivity, which allows them to detect phages with less representation in reference databases, but may be more susceptible to certain biases [13]. These differences lead to strikingly dissimilar outputs when applied to real metagenomes; in one evaluation of human gut data, nearly 80% of contigs flagged as phage were identified by only a single tool [13].

Experimental Protocols for Tool Benchmarking

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons, benchmarking studies follow rigorous experimental protocols. The methodologies below outline the creation of key datasets used to evaluate tool performance.

RefSeq Artificial Contigs and Mock Community Benchmark

This protocol tests a tool's ability to correctly identify known phage sequences and reject non-viral sequences in a controlled setting [11].

True-Positive Set Creation:

- Source: All complete phage genomes deposited in RefSeq during a specific timeframe (e.g., Jan 2020 - Aug 2021) are downloaded.

- Quality Control: Genomes are dereplicated against older RefSeq data and the training sets of the tools being benchmarked to prevent overfitting.

- Fragmentation: Quality-controlled genomes are uniformly fragmented into contigs of sizes ranging from 1 kbp to 15 kbp to simulate metagenomic assemblies.

True-Negative Set Creation:

- Source: All complete bacterial and archaeal chromosomes and plasmids from the same RefSeq timeframe are downloaded.

- Viral Content Filtering: Sequences are filtered to remove any with ≥30% of their open reading frames (ORFs) matching viral proteins in the pVOG database, ensuring they are truly non-viral.

Mock Community Analysis:

- A previously sequenced mock community containing a known set of phage species is used as an additional validation dataset [11].

Evaluation:

- Tools are run on the fragmented RefSeq and mock community datasets.

- Precision, Recall, and F1 Score are calculated based on the tools' abilities to correctly classify the true phage and true non-phage sequences.

Simulated Metagenomes and Virome Analysis

This protocol assesses tool performance under more realistic conditions, including sequencing errors, assembly artifacts, and low viral abundance [13].

Dataset Simulation:

- Read Simulation: Tools like InSilicoSeq are used to generate simulated Illumina sequencing reads from a curated set of phage, bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic genomes. This incorporates realistic error models from specific sequencing platforms.

- Metagenome Assembly: The simulated reads are assembled into contigs using standard metagenomic assemblers.

Fragment Length and Contamination Assessment:

- Reference genomes are fragmented into non-overlapping segments of various lengths (e.g., 500 bp, 1,000 bp, 3,000 bp, 5,000 bp).

- Contigs are mixed with fragments from eukaryotic genomes to test robustness against contamination.

Analysis of Real Metagenomes and Viromes:

- Tools are run on real-world datasets, such as human gut whole-community metagenomes and purified viromes.

- The resulting phage communities are compared to understand how tool choice influences ecological conclusions [13].

A Workflow for Validating Phage Ecogenomic Signatures

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for using benchmarked tools to detect and validate phage ecogenomic signatures in whole community metagenomes.

Successful phage discovery in metagenomes relies on a suite of computational tools and biological databases. The following table details key resources for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Phage Metagenomics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Phage Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| VIBRANT | Software Tool | Uses a neural network and HMMs to identify phage sequences and characterize auxiliary metabolic genes [11]. |

| VirSorter2 | Software Tool | Employs multiple random forest classifiers to detect a diverse array of viral sequences from different groups [11]. |

| Kraken2 | Software Tool | A k-mer-based taxonomic classifier that can be applied to phage detection with high precision [12] [11]. |

| DeepVirFinder | Software Tool | Applies a convolutional neural network on k-mer signatures to identify phage sequences, especially on shorter contigs [11]. |

| RefSeq | Database | A curated database of reference sequences used for training, benchmarking, and homology-based searches [11] [13]. |

| pVOG/VDB | Database | Databases of viral protein families and genomes used by tools for HMM profiling and homology detection [11]. |

| MGnify | Database | A specialized repository for microbiome metagenomic data, providing access to community-derived sequences and analyses [14]. |

| IMG/VR | Database | A system for hosting and analyzing viral genomes and metagenomes, useful for comparative analysis [14]. |

The expansion of the known phage universe through metagenomics is intrinsically linked to the computational tools used for discovery. Benchmarking studies reveal that no single tool is universally superior; each has unique strengths and weaknesses [12] [13]. Homology-based tools like VIBRANT and VirSorter2 offer high accuracy and low false positive rates, while sequence composition-based tools like DeepVirFinder can be more sensitive to novel phages absent from databases. The high-precision classifier Kraken2 is excellent for well-characterized sequences.

Therefore, the optimal strategy for validating true phage ecogenomic signals in whole community metagenomes involves a consensus-based approach. Researchers should leverage multiple tools from different methodological categories and prioritize contigs identified by several independent algorithms. This mitigates individual tool biases and provides a more robust validation of the phage ecogenomic signatures that are critical to understanding the role of viruses in microbial ecosystems and human health.

The validation of phage ecogenomic signals within whole-community metagenomes presents a formidable challenge for researchers investigating viral roles in microbial ecosystems. This guide objectively compares the performance of different methodological approaches against three core challenges: database incompleteness, the lack of universal viral markers, and host contamination. The following data, synthesized from current research, provides a framework for selecting appropriate protocols and reagents to advance phage ecogenomics.

Challenge One: Database Incompleteness and Taxonomic Errors

Database incompleteness and misannotation severely limit the accuracy of taxonomic classification in metagenomic studies. These issues are pervasive in default databases mirrored from NCBI, affecting downstream biological interpretations.

Table 1: Impact and Mitigation of Database Issues

| Issue Type | Prevalence & Impact | Performance of Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Misannotation | An estimated 1-3.6% of prokaryotic genomes in RefSeq and GenBank are misannotated [15]. | ANI Clustering: Corrected Dickeya dadantii misannotation to D. paradisiaca after comparison with type material [15]. |

| Database Contamination | 2,161,746 contaminated sequences identified in GenBank; 114,035 in RefSeq [15]. Incomplete Lineage Representation: Missing radiolarians (Retaria) led to 42,736 unannotated proteins and 46,283 misannotations in a marine transect study [16]. | Curation & Validation: FDA-ARGOS uses a restrictive, verified-sequence approach. Database testing across thousands of samples is recommended for critical applications [15]. |

| Unspecific Labeling | Annotations at high taxonomic levels (e.g., "Bacteria") preclude species-level resolution [15]. | Deep Annotation: Annotating to the deepest possible node in the taxonomic tree improves resolution [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Database-Driven Bias

A clear experimental protocol exists for quantifying the impact of database composition on taxonomic profiling [16]:

- Database Manipulation: Create modified versions of a reference database (e.g., MMETSP). For a target genus like Phaeocystis, create subsets containing (a) all references, (b) only colony-forming species, and (c) only free-living species.

- Annotation: Annotate the same set of assembled metagenomic contigs from different environments (e.g., Southern Ocean vs. Mediterranean Sea) against all three database versions using a standard lowest common ancestor (LCA) algorithm.

- Quantification: For each database, calculate the percentage of target sequences (e.g., Phaeocystis) identified. The variation in recovery rates directly demonstrates database bias.

Challenge Two: Lack of Universal Markers and Host Prediction

Unlike prokaryotes with 16S rRNA, phages lack a universal phylogenetic marker. This complicates their identification and the crucial step of host prediction. Method selection significantly influences host prediction success rates.

Table 2: Performance of Phage Identification and Host Prediction Methods

| Method | Principle | Performance Data & Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Extrachromosomal Sequencing | Selective sequencing of circular DNA (plasmidomes) to enrich for phage sequences [17]. | Identified 200 viral sequences from groundwater; 32 of 41 viral clusters represented putative new genera, demonstrating high novelty discovery [17]. |

| Tetranucleotide Frequency | Uses k-mer composition similarity between phage and host genomes [17]. | Most Productive Method: Predicted hosts for 71/200 viral genomes using public NCBI WGS and for 16/20 using local isolate genomes [17]. |

| BLAST Homology (BLAST99) | Identifies near-exact matches (e.g., >99% identity and query coverage) indicating prophage integration [17]. | Highest Confidence: Enabled strain-level host assignments. Four viruses were identified as integrated into genomes of Pseudomonas, Acidovorax, and Castellaniella strains [17]. |

| CRISPR Spacer Analysis | Matches phage sequences to CRISPR spacer arrays in bacterial genomes [17]. | Least Productive: Predicted only 2 hosts for the 200 groundwater viral genomes, highlighting limited sensitivity [17]. |

| Ecogenomic Signatures | Profiles relative abundance of phage gene homologs across diverse metagenomes to infer habitat association [10]. | Gut phage ΦB124-14 showed significantly higher signal in human gut viromes vs. environmental viromes. This signature discriminated "contaminated" environmental metagenomes in simulated faecal pollution studies [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Method Host Prediction

A robust host prediction workflow integrates multiple methods to maximize results [17]:

- Phage Genome Identification: Use a tool like VirSorter to identify viral sequences from metagenomic or plasmidome assemblies [17].

- Host Prediction with Public Databases: Run the viral sequences against a comprehensive database of bacterial WGS (e.g., from NCBI) using:

- Tetranucleotide Frequency Analysis: For broad host-range predictions.

- BLAST Homology: To find highly similar sequences.

- Host Prediction with Local Isolates: For high-confidence, strain-level assignments, repeat Step 2 using WGS from bacterial isolates sourced from the same environment. The BLAST99 approach is particularly powerful here for detecting integrated prophages.

- Validation: Cross-reference predictions from different methods. Predictions confirmed by multiple methods (e.g., both BLAST and tetranucleotide frequency) are considered high-confidence.

Challenge Three: Host Decontamination in Metagenomic Data

Host DNA contamination is a major concern, especially in low-biomass samples, and can lead to false inferences. Statistical decontamination tools are essential for generating accurate microbial community profiles.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Decontamination Tools

| Tool/Method | Underlying Principle | Performance in Experimental Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Decontam (Frequency) | Models inverse correlation between contaminant frequency and sample DNA concentration [18]. | In a human oral dataset, classifications were consistent with prior microscopic observations. Reduced technical variation in a dilution series dataset arising from different sequencing protocols [18]. |

| Decontam (Prevalence) | Identifies sequences with significantly higher prevalence in negative controls than in true samples [18]. | Corroborated the conclusion that little evidence exists for an indigenous placenta microbiome. Identified contaminants that were low-frequency taxa associated with preterm birth [18]. |

| Relative Abundance Threshold | Ad hoc removal of sequences below an abundance cutoff (e.g., 0.1%) [18]. | Poor Performance: Removes rare but true sequences and fails to remove abundant contaminants, which are most likely to interfere with analysis [18]. |

| Negative Control Subtraction | Removal of all sequences found in negative controls [18]. | Limited Specificity: Can remove true sequences that appear in controls due to cross-contamination or index hopping [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: In Silico Decontamination with Decontam

The decontam R package provides a straightforward statistical workflow [18]:

- Input Data Preparation: Create a feature table (ASV or OTU table) and a corresponding sample metadata file.

- Define Method: Choose the decontamination method based on available data:

- Frequency-Based: Requires quantitative DNA concentration measurements for each sample.

- Prevalence-Based: Requires sequenced negative controls processed alongside biological samples.

- Execution: Run the

isContaminant()function in R, specifying the chosen method and threshold. The function returns a logical vector identifying which features are classified as contaminants. - Result Application: Remove the contaminant features from the feature table before proceeding with downstream ecological analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Databases

Table 4: Key Reagents and Databases for Phage Ecogenomics

| Research Material | Function in Workflow | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VirSorter | Identifies viral sequences from metagenomic assemblies [17]. | Critical first step for virome analysis from complex metagenomic data. |

| Decontam (R Package) | Statistically identifies and removes contaminant DNA sequences from marker-gene and metagenomic data [18]. | Integrates easily with existing MGS workflows; uses frequency or prevalence patterns. |

| NCBI RefSeq/GenBank | Primary public repositories for nucleotide sequences used as reference databases [15]. | Known to contain contamination and taxonomic errors; requires curation for critical work [15]. |

| MMETSP Database | Curated database of marine microbial eukaryote transcriptomes [16]. | Used for taxonomic annotation of protists; missing key groups like radiolarians [16]. |

| Bacterial Whole-Genome Sequences (Local Isolates) | High-confidence reference for host prediction of phages from the same environment [17]. | Dramatically improves strain-level host prediction compared to public databases alone [17]. |

| Filamentous Phage (e.g., M13) | Vector for phage display technology; used for epitope mapping and protein interaction studies [19] [20]. | pIII and pVIII are common coat proteins for fusion [19]. |

| Phagemid Vectors | Hybrid vectors containing phage and plasmid origins of replication; used for antibody display [19]. | Requires a helper phage (e.g., M13KO7) for packaging into a viral particle [19]. |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Logical Relationships

Phage Ecogenomic Validation Workflow

Database Issue Impact on Annotation

Bacteriophages, the most abundant biological entities in most ecosystems, encode distinct habitat-associated signals derived from co-evolution and adaptation with their bacterial hosts. The identification and validation of these ecogenomic signatures in whole community metagenomes present both a significant challenge and opportunity for advancing microbial ecology and therapeutic development. These signatures manifest through the relative abundance of phage-associated genes, protein cluster distributions, and contextual genomic features that serve as reliable indicators of phage lifestyle, host interactions, and ecological functions [21]. The precision with which these signals can be interpreted directly impacts diverse applications ranging from microbial source tracking in environmental samples to the development of targeted phage therapies for combating antibiotic-resistant infections [22].

Recent technological advances in sequencing platforms and bioinformatics tools have dramatically expanded our capacity to detect and analyze phage sequences within complex microbial communities. However, the validation of ecogenomic signals requires careful consideration of methodological approaches, as demonstrated by studies showing that individual phage genomes like φB124-14 encode discernible habitat-related signatures that can successfully distinguish human gut viromes from other environmental sources [21]. This evolving capability to interpret phage genomic signals within whole community metagenomes represents a transformative development for both basic research and applied biotechnology.

Computational Tool Performance for Phage Detection

The accurate identification of phage sequences within metagenomic data represents the foundational step in ecogenomic signal interpretation. A comprehensive benchmark evaluation of nine computational phage detection tools revealed striking differences in their performance characteristics and output results [13].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Phage Detection Tools on Benchmark Datasets

| Tool | Approach | Sensitivity on Short Fragments (<3kb) | Robustness to Eukaryotic Contamination | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhaMer | Protein-cluster Transformer | High (contextual embedding) | High | Superior F1-score on real metagenomic data | Computational complexity |

| VirSorter2 | Homology (random forest) | Moderate | High | Low false positive rate | Database dependence |

| DeepVirFinder | Sequence composition (CNN) | High | Moderate | Sensitive to novel phages | Higher false positives |

| VirFinder | Sequence composition (k-mer) | Moderate | Moderate | k-mer frequency analysis | Lower precision |

| MARVEL | Homology | Low | High | Specificity | Limited sensitivity on short fragments |

| MetaPhinder | Alignment-based | Low | Moderate | Handles phage mosaicism | Limited to reference genomes |

Tools generally fall into two methodological categories: homology-based approaches (VirSorter, MARVEL, viralVerify, VIBRANT, and VirSorter2) that utilize reference databases to identify viral hallmark genes, and sequence composition approaches (VirFinder, DeepVirFinder, Seeker) that employ machine learning models trained on sequence features such as k-mer frequencies [13]. The benchmark analysis demonstrated that homology-based tools typically exhibit lower false positive rates and greater robustness to eukaryotic contamination, while composition-based tools show higher sensitivity, particularly for phages with poor representation in reference databases [13].

The practical implications of these methodological differences are substantial, with the same human gut metagenomes yielding dramatically different predicted phage communities depending on the tool employed. In one assessment, nearly 80% of contigs were marked as phage by at least one tool, with a maximum overlap of only 38.8% between any two tools [13]. This discrepancy highlights the critical importance of tool selection based on specific research objectives, whether prioritizing comprehensive discovery (favoring sensitivity-oriented tools) or confident identification of known phage types (favoring specificity-oriented tools).

Emerging Solutions: Transformer-Based Models

The recently developed PhaMer tool represents a significant advancement by applying a state-of-the-art Transformer model to phage identification. This approach constructs a protein-cluster vocabulary and uses contextual embedding to learn both protein composition and organizational patterns within contigs [23]. The self-attention mechanism enables the model to recognize important protein associations indicative of phage sequences, similar to how language models understand word relationships in sentences [23].

On multiple benchmark datasets, including simulated metagenomic data and public IMG/VR datasets, PhaMer outperformed existing state-of-the-art tools, improving the F1-score of phage detection by 27% on mock metagenomic data [23]. This demonstrates the power of leveraging protein-level contextual information rather than relying solely on sequence composition or isolated homology searches.

Experimental Protocols for Signal Validation

Ecogenomic Signature Profiling Protocol

The validation of phage ecogenomic signals requires systematic approaches that bridge computational predictions with experimental verification. A established protocol for detecting habitat-specific signatures involves:

Reference Genome Selection: Curate complete phage genomes with known habitat associations (e.g., φB124-14 for human gut, φSYN5 for marine environments) [21].

Metagenomic Dataset Curation: Assemble diverse metagenomic datasets representing target and control habitats (human gut, other body sites, environmental samples) from public repositories [21].

ORF Homology Analysis: Calculate cumulative relative abundance of sequences with similarity to reference phage ORFs in each metagenome using BLAST or DIAMOND with optimized thresholds (e-value < 1e-5, identity > 30%) [21].

Statistical Validation: Perform comparative analysis of relative abundance profiles across habitats using appropriate non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U for habitat comparisons) with multiple test correction [21].

Discriminatory Power Assessment: Apply machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest) to evaluate the predictive capability of identified signatures for habitat classification, using cross-validation to assess performance [21].

This protocol successfully demonstrated that the φB124-14 ecogenomic signature could distinguish human gut viromes from other environmental data sets and detect simulated human fecal contamination in environmental metagenomes [21].

Marker Gene Integration Protocol

For simultaneous assessment of phage and bacterial dynamics in longitudinal studies, the Marker-MAGu pipeline provides a robust methodological framework:

Phage Genome Catalog Construction: Compile comprehensive phage databases from public resources (Trove of Gut Virus Genomes - TGVG) containing species-level genome bins clustered at 95% average nucleotide identity [9].

Essential Gene Annotation: Identify phage-specific marker genes involved in virion structure, genome packaging, and replication using conserved domain databases (Pfam, TIGRFAM) [9].

Marker Gene Integration: Incorporate viral marker genes into established bacterial profiling databases (MetaPhlAn 4) to create trans-kingdom taxonomic profiling resources [9].

Validation: Assess specificity and sensitivity using simulated read data across coverage levels (0.1-10×), with expected performance showing high specificity at all coverage levels and high sensitivity above 0.5× coverage [9].

This approach enabled the analysis of 12,262 longitudinal samples from 887 children, revealing that phage communities change more rapidly than bacterial communities, with most phages persisting for shorter durations in individual hosts [9].

Figure 1: Workflow for detecting and validating phage ecogenomic signals from metagenomic data, showing the progression from raw data to practical applications.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ecogenomic Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Phage Ecogenomic Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Description | Application in Ecogenomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Phage Database (OPD) | Database | 189,859 representative phage genomes from 5,427 metagenomic samples [6] | Reference for oral phage ecogenomic signatures |

| Chicken Virome Database (CVD) | Database | 17,268 species-level vOTUs from chicken gastrointestinal tract [24] | Agricultural and zoonotic phage studies |

| Trove of Gut Virus Genomes (TGVG) | Database | 110,296 viral species-level genome bins from human gut [9] | Human gut phage marker gene source |

| Marker-MAGu | Bioinformatics Tool | Pipeline for trans-kingdom taxonomic profiling using phage marker genes [9] | Simultaneous phage-bacteria dynamics |

| CheckV | Quality Tool | Genome completeness assessment and contamination estimation [24] | Quality control for phage genomes |

| geNomad | Classification Tool | Taxonomic classification of viral sequences using ICTV database [24] | Standardized taxonomy assignment |

| iPHoP | Host Prediction | Integrated machine learning framework with multiple prediction approaches [24] | Phage-host relationship mapping |

The creation of habitat-specific phage databases has been instrumental in advancing ecogenomic studies. The Oral Phage Database (OPD), for example, was constructed from 5,427 metagenomic samples and 2,178 cultivated bacterial genomes, revealing remarkably distinct phage compositions compared to gut virome catalogs, with 64.8% of viral clusters comprising only a single member, indicating extensive novel diversity [6]. Similarly, the Chicken Virome Database (CVD) demonstrated minimal overlap with existing virome databases, highlighting the necessity for specialized resources tailored to specific ecosystems [24].

These curated resources enable researchers to move beyond generic viral detection to habitat-specific signature identification. For instance, the OPD facilitated the discovery that oral phages carry an array of anti-defense genes, auxiliary metabolic genes, and virulence factors that may influence bacterial metabolism and human health [6]. The compositional analysis enabled by these databases further revealed that oral phage composition varies among different populations, with several phages showing potential as biomarkers for disease [6].

Case Studies in Ecogenomic Signal Validation

Microbial Source Tracking with φB124-14

The application of ecogenomic signatures for microbial source tracking (MST) represents a compelling case study in practical validation. Research demonstrated that the human gut-associated phage φB124-14 encodes a distinct ecogenomic signature that enables discrimination of human fecal contamination in environmental waters [21].

The validation process involved analyzing the representation of φB124-14 open reading frames (ORFs) across diverse viral metagenomes from human, porcine, and bovine guts, alongside various aquatic environments. Results showed a significantly greater mean relative abundance of φB124-14-encoded ORFs in human gut viromes compared with environmental datasets [21]. This pattern was specific to φB124-14, as control phages from other habitats (marine cyanophage φSYN5 and plant rhizosphere-associated φKS10) showed distinctly different distribution patterns [21].

Notably, this signature remained detectable in whole community metagenomes, where φB124-14 ORFs showed significantly greater representation in human-derived data sets compared to other phages [21]. The robustness of this ecogenomic signal enabled the development of a sensitive detection method for human fecal pollution, demonstrating the practical utility of validated phage ecogenomic signatures in environmental monitoring.

Lifestyle Cues from Temperate Phage Induction

The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation provides particularly compelling evidence for ecogenomic signals related to phage lifestyle. A comprehensive study of temperate phages from the human gut demonstrated that only 18% of computationally predicted prophages could be experimentally induced in pure cultures, highlighting the limitations of prediction-only approaches [25].

However, when bacterial isolates were co-cultured with human colonic cells (Caco2), the induction rate increased to 35% of phage species, indicating that human host-associated cellular products act as induction triggers [25]. This finding was further validated by showing that Caco2 cell lysates specifically induced 25 prophages from 32 bacterial isolates, 9 of which had not been detected using standard induction agents [25].

These results establish a crucial link between human gastrointestinal cell lysis and temperate phage induction, providing both a methodological framework for lifestyle validation and insight into the complex ecological relationships between phages, their bacterial hosts, and human cells [25]. The study further identified polylysogeny as a common feature, with coordinated prophage induction influenced by divergent integration sites [25].

Figure 2: Experimental validation workflow for temperate phage induction, showing increased detection through human cell co-culture compared to standard methods and computational prediction alone.

The interpretation of phage ecogenomic signals in whole community metagenomes has evolved from a theoretical possibility to a practical methodology with diverse applications. The successful validation of these signatures requires methodological pluralism - integrating multiple computational approaches with experimental verification to overcome the limitations inherent in any single method.

Key advances include the development of habitat-specific phage databases that capture previously undocumented diversity, the creation of sensitive computational tools that leverage both homology and sequence composition features, and the establishment of standardized experimental protocols for verifying predicted ecological relationships. The demonstrated capability of phage ecogenomic signatures to distinguish microbial habitats and track environmental contaminants confirms their utility as reliable biological indicators.

Future progress will depend on continued refinement of computational methods, expansion of reference databases to encompass greater phage diversity, and development of novel experimental approaches for validating phage-host interactions in complex communities. As these methodologies mature, the systematic interpretation of phage ecogenomic signals will increasingly enable researchers to decipher the ecological dynamics and functional potential of viral communities across diverse ecosystems.

The Phage Miner's Toolkit: Methodologies for Detection and Analysis in Metagenomic Data

The validation of phage ecogenomic signals in whole community metagenomes represents a frontier in microbial ecology, with profound implications for understanding human health, environmental processes, and therapeutic development [21]. This research aims to identify habitat-specific genetic patterns encoded by bacteriophages that can distinguish microbial ecosystems, offering potential for novel diagnostic tools and microbial source tracking [21]. However, a fundamental challenge persists: the accurate computational identification of phage sequences within complex metagenomic datasets, a critical first step before any ecogenomic analysis can be performed.

Unlike prokaryotes, which possess universal marker genes like 16S rRNA, viruses lack such conserved features, making their detection and classification particularly challenging [26] [13]. In response to this challenge, two distinct computational archetypes have emerged: homology-based detectors and sequence composition-based detectors. These approaches leverage fundamentally different principles for phage identification, each with characteristic strengths and limitations that researchers must understand to effectively validate phage ecogenomic signals.

Tool Archetypes: Core Principles and Mechanisms

Homology-Based Detection Approach

Homology-based tools operate on the principle of evolutionary conservation, identifying phage sequences by detecting similarity to known viral elements in reference databases [27] [26]. These tools utilize sequence alignment algorithms—such as BLAST, HMMER, or DIAMOND—to search for homologous genes or protein domains that serve as viral hallmarks [27] [13]. The underlying assumption is that phage genomes encode conserved features, such as specific structural proteins or replication-associated genes, that persist across evolutionary time and can be detected through significant sequence similarity [28].

This approach typically involves searching for enrichment of viral hallmark genes, depletion of cellular genes, and specific genomic architectures such as strand shifts that characterize phage genomes [26] [13]. Tools like VirSorter, VIBRANT, and VirSorter2 exemplify this approach, incorporating probabilistic models or machine learning classifiers that integrate multiple homology-based features to make predictions [13] [11]. The statistical significance of alignments is crucial, with expectation values (e-values) quantifying the likelihood that observed similarity occurred by chance, thus providing a foundation for inferring homology and, by extension, common evolutionary ancestry [28].

Sequence Composition-Based Detection Approach

In contrast, sequence composition-based tools abandon evolutionary relationships in favor of intrinsic sequence properties, utilizing machine learning models trained on patterns distinguishing viral from non-viral DNA [26] [13]. These tools analyze features such as k-mer frequencies (short DNA sequences of length k), oligonucleotide patterns, codon usage bias, and GC content [29] [13].

The fundamental premise is that phage genomes possess distinct compositional signatures that differ from those of their bacterial hosts and other biological elements, patterns that persist even in the absence of detectable sequence similarity [29]. Tools like VirFinder, DeepVirFinder, and Seeker implement this approach using various machine learning architectures, including logistic regression, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to recognize these complex patterns [13] [11]. Because they do not require multiple open reading frames for classification, composition-based methods can effectively identify phage sequences in fragmentary metagenomic data where gene-based approaches struggle [26].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Phage Detection Archetypes

| Feature | Homology-Based Approach | Sequence Composition-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Evolutionary conservation through sequence similarity | Intrinsic genomic signatures and patterns |

| Detection Mechanism | Alignment to reference databases of known phage proteins/genes | Machine learning models trained on k-mer frequencies and compositional biases |

| Key Advantages | High specificity, well-understood false positive rates, robustness to eukaryotic contamination | Detection of novel phages absent from databases, effectiveness on short sequence fragments |

| Primary Limitations | Limited to known phage diversity, database dependence, poor detection of highly divergent phages | Black-box decision process, potential environmental bias in training data, higher false positive rates |

| Representative Tools | VirSorter2, VIBRANT, viralVerify, MARVEL, MetaPhinder | VirFinder, DeepVirFinder, Seeker, PPR-Meta |

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

Independent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the performance of these tool archetypes across multiple dimensions, providing critical empirical data to guide tool selection [26] [13] [11]. These assessments reveal consistent patterns in how each archetype performs under different experimental conditions.

Performance on Reference Genome Fragments

Benchmarks using fragmented reference genomes have demonstrated that sequence composition-based tools generally achieve higher sensitivity for shorter contigs (<3 kbp), while homology-based tools excel with longer sequences where sufficient gene content is available for analysis [26]. This performance gap narrows significantly as contig length increases, with homology-based approaches achieving superior F1 scores (a harmonic mean of precision and recall) on fragments of 5 kbp and longer [11].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Benchmark Studies

| Performance Metric | Homology-Based Tools | Sequence Composition-Based Tools | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Score (RefSeq contigs) | 0.93 (VIBRANT, VirSorter2) [11] | 0.70-0.86 (DeepVirFinder, Kraken2) [11] | Higher indicates better balance of precision and recall |

| False Positive Rate | Low (0.5-3%) [26] [13] | Moderate to High (5-15%) [26] [13] | Measured on shuffled sequences and non-viral genomes |

| Robustness to Eukaryotic Contamination | High [26] | Variable [26] | Resistance to false positives from non-target sequences |

| Sensitivity to Novel Phages | Limited [26] [13] | High [26] [13] | Detection of phages not represented in reference databases |

| Computational Resource Requirements | Moderate to High [26] | Low to Moderate [26] | Varies by tool and database size |

Performance on Real Metagenomic Datasets

When applied to real human gut metagenomes, the differences between tool archetypes become strikingly apparent. Benchmarking reveals that nearly 80% of contigs are marked as phage by at least one tool, with a maximum overlap of only 38.8% between any two tools [26]. This discrepancy highlights the complementary nature of these approaches, with each detecting different segments of the viral community.

The consensus is more substantial in purified viromes, where tools achieve up to 60.65% overlap in predictions, though differences remain significant [26]. This suggests that the choice of tool archetype substantially influences the resulting biological interpretations, particularly in complex whole-community metagenomes where phage sequences represent a minority component amidst abundant host DNA [26] [11].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Genome Fragment Benchmark Construction

To assess tool performance across critical parameters, researchers have developed standardized benchmark datasets and protocols [26] [13]. The genome fragment set is constructed by downloading complete bacterial, archaeal, and viral genomes from RefSeq, followed by fragmentation into non-overlapping adjacent fragments of specified lengths (typically 500, 1,000, 3,000, and 5,000 nucleotides) [26]. To ensure unbiased evaluation, sequences are carefully dereplicated against training sets of the tools being evaluated to prevent overfitting [11]. This dataset enables systematic assessment of fragment length effects, low viral content robustness, taxonomic biases, and resistance to eukaryotic contamination [26].

Simulated Metagenome Workflow

For evaluating performance under realistic sequencing conditions, benchmarkers employ simulated metagenomes using tools like InSilicoSeq, which incorporates realistic error models trained on real sequencing reads from platforms including MiSeq, HiSeq, and NovaSeq [13]. This approach allows controlled assessment of sequencing error impacts, assembly quality effects, and viral abundance variations [13]. The workflow involves: (1) read simulation from phage genomes using empirically-derived error models, (2) metagenomic assembly with tools like MetaSPAdes or MEGAHIT, and (3) comparative tool evaluation on the resulting contigs [26] [13].

Validation on Mock Communities and Real Samples

The most rigorous validation incorporates mock communities with known composition and real metagenomic datasets from specific environments [11]. Mock communities containing precisely defined phage species enable calculation of ground-truth precision and recall metrics [11]. Complementary analysis of real samples—such as human gut metagenomes from healthy and diseased individuals—assesses performance under authentic research conditions and reveals potential biases affecting ecological interpretations [26] [11].

Diagram 1: Phage Detection Tool Benchmark Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Resources for Phage Detection Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function in Phage Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | RefSeq Viral, pVOGs, ViPhOG, custom phage databases | Provide curated sets of known phage proteins and genomes for homology-based detection |

| Sequence Alignment Tools | BLAST, HMMER, DIAMOND | Identify statistically significant similarity between query sequences and reference databases |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Enable development and application of composition-based detection models |

| Metagenomic Assemblers | MetaSPAdes, MEGAHIT, viralFlye | Reconstruct longer contigs from short-read sequencing data to improve detection |

| Benchmarking Datasets | RefSeq fragments, simulated phageomes, mock communities | Standardized datasets for tool performance evaluation and comparison |

| Visualization & Analysis | PhageScope, Pavian, Anvi'o | Interpret and visualize phage detection results in biological context |

Implications for Phage Ecogenomic Signal Validation

The choice between homology-based and composition-based detection approaches carries profound implications for validating phage ecogenomic signatures in whole community metagenomes [21]. Homology-based methods provide high-specificity detection suitable for tracking known phage lineages across environments, essential for establishing reproducible ecogenomic patterns [21] [26]. However, their database dependence may overlook novel phage taxa encoding potentially important habitat-associated signals.

Conversely, composition-based tools can identify these novel elements, potentially revealing previously undetected ecogenomic patterns, but at the cost of higher false discovery rates that may introduce noise into signature validation [26]. For research focused on discovering novel habitat associations, composition-based tools offer clear advantages, while homology-based approaches provide greater confidence when tracking specific phage groups across sample types [21] [26].

The most robust strategy for ecogenomic signal validation employs a consensus approach, leveraging both archetypes to maximize detection breadth while maintaining confidence in predictions [26] [11]. This is particularly important for whole community metagenomes, where phage sequences represent a minute fraction of total DNA and require highly sensitive yet specific tools for accurate characterization [21] [26].

Diagram 2: Complementary Approaches for Ecogenomic Signal Validation

The validation of phage ecogenomic signals in whole community metagenomes demands careful consideration of computational detection approaches. Homology-based and sequence composition-based detectors offer complementary strengths—the former providing specificity and reliability for known phages, the latter enabling discovery of novel elements potentially encoding important habitat signatures [26] [13] [11].

For researchers pursuing ecogenomic signature validation, a tiered strategy is recommended: initial discovery using composition-based tools to maximize sensitivity, followed by confirmation with homology-based methods to ensure specificity, and culminating in consensus approaches that leverage both archetypes [26] [11]. This multifaceted methodology provides the most robust foundation for identifying authentic phage-encoded ecogenomic signatures diagnostic of underlying microbiomes, ultimately advancing applications in microbial source tracking, ecosystem monitoring, and therapeutic development [21].

As phage detection tools continue to evolve, ongoing benchmarking against standardized datasets remains essential for understanding methodological biases and advancing the rigorous validation of ecogenomic signals in complex microbial communities [26] [13] [11].

The exploration of viral diversity, particularly bacteriophages, within complex microbial communities relies heavily on advanced computational tools to identify viral sequences from metagenomic data. The challenge of accurately distinguishing viral signals from host and other non-viral sequences is central to validating phage ecogenomic signals in whole-community metagenomes. This guide objectively compares the performance and methodologies of three prominent tools—VirSorter2, DeepVirFinder, and the integrated pipeline MetaPhage—providing researchers with a framework for selecting and implementing robust viral discovery workflows.

Tool Comparison: Performance and Experimental Data

Independent benchmarking studies provide critical quantitative data for comparing the accuracy and efficiency of viral identification tools. The following metrics are primarily derived from a 2024 benchmark study that evaluated tools on mock metagenomes composed of taxonomically diverse sequences [30].

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Viral Discovery Tools

| Tool (Version) | Algorithmic Approach | Optimal Sequence Length | Reported Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VirSorter2 | Multi-classifier, random forest based on genomic features & hallmark genes [31] | >3 kb [30] | 0.77 (in high-accuracy rulesets) [30] | High accuracy across diverse viral groups; minimizes false positives from plasmids/eukaryotic DNA [31] [30] | Performance depends on database representation of viral groups [31] |

| DeepVirFinder | k-mer based deep learning (Convolutional Neural Network) [30] | < 2,100 kb; >3 kb for optimal accuracy [30] | Included in some high-accuracy rulesets [30] | Machine learning approach; does not rely solely on homology [30] | Can misclassify atypical cellular sequences (e.g., plasmids) [31] |

| VIBRANT | Hybrid machine learning and protein similarity (HMMs) [30] | >3 kb [30] | Included in some high-accuracy rulesets [30] | Classifies viral genomes into quality categories (High, Medium, Low) [30] | Not a primary focus of this benchmark |

| MetaPhage | Integrated pipeline (VirSorter2, DeepVirFinder, VIBRANT, etc.) with graphanalyzer [32] | Application-dependent (uses underlying tools) | Not independently benchmarked in search results | Automated, reproducible workflow from reads to report; includes taxonomic classification [32] | Performance is an aggregate of constituent tools |

The benchmark concluded that the highest accuracy (MCC = 0.77) was achieved by several "rulesets" (combinations of tools), with the most consistent containing VirSorter2 [30]. A key finding was that simply combining more tools does not improve performance and can increase non-viral contamination. The study recommends a ruleset employing VirSorter2 paired with a "tuning removal" rule to filter out false positives [30].

Table 2: Tool Specialization and Supported Viral Groups

| Tool | dsDNA Phages (Caudovirales) | ssDNA Viruses | RNA Viruses | NCLDVs | Archaeal Viruses | Prophage Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VirSorter2 | Yes (Primary focus) [31] | Yes [31] | Yes [31] | Yes [31] | Implied (across diverse groups) | Yes [31] |

| DeepVirFinder | Yes (Primary focus) [30] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Limited (trained mainly on prokaryotes) [30] | Not Specified |

| VIBRANT | Yes [30] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Yes [30] |

| MetaPhage | Yes (via constituent tools) [32] | Yes (via constituent tools) [32] | Yes (via constituent tools) [32] | Yes (via constituent tools) [32] | Yes (via constituent tools) [32] | Yes (via constituent tools) [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking and Validation

The quantitative data in Table 1 stems from a rigorous benchmarking methodology. Understanding this protocol is essential for contextualizing the results and for designing validation experiments within a research project.

Benchmarking Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key steps for creating a standardized testing environment to evaluate viral identification tools, as performed in the cited study [30].

Key Experimental Steps:

- Creation of a Mock Metagenome: A standardized testing set is created by downloading genomic sequences from NCBI RefSeq and other validated sources (like the VirSorter2 database) for various sequence types: viral, bacterial, archaeal, plasmid, protist, and fungal [30].

- Stratified Sampling: Sequences are randomly sampled with replacement to generate a mock metagenome that mimics the composition of a cellular-enriched metagenome, typically containing around 10% viral sequences amongst a majority of bacterial and other non-viral sequences [30].

- Sequence Length Trimming: To ensure fair comparison, all sequences are often trimmed to a maximum length (e.g., 2,100 kb for DeepVirFinder compatibility) and a minimum length (e.g., 3 kb, where tool accuracy is more stable) [30].

- Tool Execution and Analysis: Each tool is run on the identical mock metagenome. Predictions are compared against the ground-truth labels, and performance metrics like the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) are calculated to evaluate accuracy while accounting for class imbalance [30].

Validation in Environmental Metagenomes

Beyond mock data, tools should be validated on real environmental metagenomes. A common strategy involves using virus-enriched metagenomes (e.g., prepared via cesium chloride density gradients) as a benchmark for evaluating tools run on whole-community metagenomes from the same sample. This approach can reveal how the degree of viral enrichment in a sample impacts tool performance, with higher viral fractions (44-46%) yielding more confident identifications compared to complex whole-community metagenomes (7-19% viral sequences) [30].

Implementing an Integrated MetaPhage Workflow

The MetaPhage pipeline exemplifies the trend towards integrated, scalable workflows that combine multiple best-in-class tools to streamline the viral discovery process [32].

MetaPhage Architectural Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow of the MetaPhage pipeline, from raw sequencing reads to a final classified report [32].

Workflow Component Details:

- Read Processing and Assembly: The pipeline begins with standard quality control (QC) and filtering of raw reads, followed by de novo assembly to reconstruct longer contigs from short reads [32].

- Modular Phage Mining: MetaPhage does not rely on a single algorithm. Instead, it streamlines the execution of multiple state-of-the-art phage miners, such as VirSorter2, DeepVirFinder, and VIBRANT, in a single, integrated workflow [32].

- Clustering and Taxonomy: Identified viral contigs are clustered into viral Operational Taxonomic Units (vOTUs) to reduce redundancy. A critical step is taxonomic classification using vConTACT2, which creates a protein-sharing network. MetaPhage enhances this with a novel graphanalyzer script that automatically parses this network to assign taxonomy to each vOTU based on its proximity to reference genomes, approximating ICTV taxonomic levels [32].

- Reproducibility and Reporting: Implemented in Nextflow, the pipeline ensures scalability and reproducibility across different computing environments (local, HPC, cloud). It consolidates all results into a comprehensive HTML report for easy interpretation [32].

Successful implementation of these computational pipelines relies on a foundation of key databases, software, and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Viral Discovery | Relevance to Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pfam / Custom HMM DB | Protein Family Database | Provides profile HMMs for identifying viral hallmark genes (e.g., capsid proteins, terminase) [31] | Used by VirSorter2 & VIBRANT for feature annotation [31] [30] |

| RefSeq Virus Database | Curated Genome Database | Source of reference viral genomes for training and validation [30] | Used for benchmarking and as a reference in tools like Kaiju [30] |

| vConTACT2 | Computational Tool | Clusters viral genomes into taxa based on protein content similarity [32] | Core component of MetaPhage for taxonomic classification [32] |

| CheckV | Computational Tool | Estimates genome completeness, identifies host contamination in viral contigs [30] | Used for quality assessment and "tuning removal" in benchmarking [30] |

| Nextflow | Workflow Manager | Orchestrates complex, multi-step pipelines ensuring reproducibility and scalability [32] | Execution engine for the MetaPhage pipeline [32] |

| Docker / Singularity | Containerization Platform | Packages tools and dependencies into isolated, portable environments [32] | Ensures consistent execution of pipelines like MetaPhage [32] |

The move towards integrated discovery pipelines represents a maturation of the field, addressing the critical need for reproducibility, scalability, and comprehensive analysis in phage ecogenomics. While individual tools like VirSorter2 demonstrate high standalone accuracy, the complexity of viral discovery from whole-community metagenomes often necessitates a multi-faceted approach. Benchmarks show that strategic, minimal tool combinations—not simply using every available tool—yield the best results. Pipelines like MetaPhage offer a robust solution by embedding these best practices into a standardized, automated framework, thereby accelerating the validation of ecogenomic signals and enhancing our understanding of the global virosphere.

The field of viral metagenomics has witnessed an explosion in data, generating millions of viral sequences from diverse ecosystems ranging from the human gut to global aquifers. This deluge of sequence information has overwhelmed traditional bioinformatics methods, creating an urgent need for robust, scalable approaches to categorize viral diversity in a biologically meaningful way. Clustering viral sequences into viral Operational Taxonomic Units (vOTUs) has emerged as a fundamental methodology for reducing complexity while preserving ecological and evolutionary signals within viral communities. This process is particularly crucial for validating phage ecogenomic signals in whole-community metagenomes, as it enables researchers to distinguish between genuine biological patterns and computational artifacts. The vOTU concept, typically applied at the species-level clustering threshold of 95% average nucleotide identity (ANI) over 85% of the shorter sequence, provides a standardized framework for comparing viral populations across studies and ecosystems [33] [34].

The analytical challenge is substantial—recent studies have identified thousands to hundreds of thousands of vOTUs within individual ecosystems. For instance, groundwater ecosystems have revealed 468 high-quality vOTUs [35], while the Japanese population-level gut virome study identified 1,347 vOTUs [33], and the Early-Life Gut Virome (ELGV) catalog expanded this to 82,141 vOTUs [34]. This dramatic expansion of viral diversity underscores the critical importance of clustering methodologies that are both computationally efficient and biologically accurate. Without proper clustering techniques, researchers risk either oversplitting viral populations (thereby inflating diversity estimates) or overlumping distinct viral lineages (obscuring true ecological patterns). This comparative guide examines the current landscape of vOTU clustering tools and methodologies, providing experimental data to inform tool selection for researchers validating phage ecogenomic signals in metagenomic studies.

Methodological Framework for vOTU Clustering

Standardized Bioinformatics Workflow

The process of clustering viral sequences into vOTUs follows a structured bioinformatics workflow that begins with viral sequence identification and culminates in ecological interpretation. Figure 1 illustrates the standard pipeline, highlighting the critical clustering step where tool selection dramatically impacts downstream results.

Figure 1. Standard bioinformatics workflow for vOTU clustering. The clustering step (green) is where tool selection occurs, with algorithm choice and parameter settings significantly impacting results. Dashed red lines indicate decision points that researchers must address.

The initial steps involve identifying viral sequences from metagenomic assemblies using tools such as VirSorter2 [36], VIBRANT [36] [3], and DeepVirFinder [36] [35], followed by quality assessment with CheckV [3] [34]. The subsequent clustering phase typically employs a standard threshold of 95% ANI over 85% alignment fraction (AF) of the shorter sequence to define vOTUs at the species level [33] [34]. This threshold is endorsed by the Minimum Information about an Uncultivated Virus Genome (MIUViG) standards and has been widely adopted across virome studies [37] [34]. The alignment fraction requirement ensures that sufficient genomic similarity exists between clustered sequences, preventing the grouping of distantly related viruses that might share only highly conserved regions.

Experimental Benchmarking Approaches

Evaluating vOTU clustering tools requires rigorous benchmarking against reference datasets with known taxonomy. The most comprehensive benchmarks utilize multiple assessment strategies: (1) accuracy of ANI estimation compared to expected values from simulated mutations; (2) agreement with authoritative taxonomy from the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV); (3) sensitivity in recovering known relationships using metrics like the number of correctly identified pairs meeting MIUViG thresholds; and (4) computational efficiency measured by runtime and memory usage on standardized datasets [37]. These metrics collectively assess both biological accuracy and practical utility, enabling informed tool selection based on research priorities—whether maximum accuracy, computational efficiency, or a balance of both.

Comparative Analysis of vOTU Clustering Tools

Tool Performance Benchmarking

Table 1 summarizes the performance characteristics of major vOTU clustering tools based on published benchmark studies. The recently developed Vclust demonstrates particularly strong performance across multiple metrics, offering alignment-based accuracy with computational efficiency previously only available through k-mer-based approximations.

Table 1: Performance comparison of vOTU clustering tools

| Tool | Algorithm Type | ANI Accuracy (MAE) | Agreement with ICTV Taxonomy | Processing Speed | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vclust [37] | Alignment-based (Lempel-Ziv parsing) | 0.3% | 95% (species) | ~40,000× faster than VIRIDIC | Large-scale metagenomic studies, reference database construction |

| VIRIDIC [37] | Alignment-based | 0.7% | 90% (species) | Baseline (slow) | Small datasets, validation studies |

| FastANI [37] | k-mer-based (sketching) | 6.8% | 40% (species) | >6× faster than Vclust | Initial exploratory analysis, very large datasets |

| skani [37] | k-mer-based (sparse alignments) | 21.2% | 27% (species) | >6× faster than Vclust (fastest mode: 7× faster than Vclust) | Extremely large datasets where speed is prioritized |

| MMseqs2 [37] | k-mer-based & alignment | N/A | N/A | ~1.5× slower than Vclust | General sequence clustering including non-viral sequences |

| MegaBLAST + anicalc [37] | Alignment-based | <1% | 97% of pairs recovered | >115× slower than Vclust | Gold-standard validation, small datasets |

Vclust introduces three innovative components that explain its performance advantages: (1) Kmer-db 2 for rapid identification of related genomes using k-mers; (2) LZ-ANI, a Lempel-Ziv parsing-based algorithm that identifies local alignments and calculates overall ANI from aligned regions; and (3) Clusty, which implements six clustering algorithms optimized for sparse distance matrices with millions of genomes [37]. This integrated approach enables Vclust to maintain alignment-based accuracy while achieving computational speeds previously only possible with less accurate k-mer-based methods.

Accuracy Metrics and Experimental Validation