Validating Ecogenomic Signatures: From Microbial Habitats to Biomedical Applications

This article explores the validation of ecogenomic signatures—habitat-specific genetic patterns that distinguish microbial communities across environments.

Validating Ecogenomic Signatures: From Microbial Habitats to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the validation of ecogenomic signatures—habitat-specific genetic patterns that distinguish microbial communities across environments. For researchers and drug development professionals, we examine the foundational principles that enable signature discovery in diverse habitats, from the human gut to contaminated soils. The review covers cutting-edge computational methods, including machine learning and composite genomic signatures, for reliable species identification and source tracking. We address critical challenges in signature discrimination and optimization, particularly for closely related taxa, and present rigorous validation frameworks applied in clinical and environmental case studies. This synthesis provides a comprehensive roadmap for employing ecogenomic signatures in biomedical research, drug discovery, and clinical diagnostics.

Decoding Habitat-Specific Genetic Blueprints: Principles of Ecogenomic Signature Discovery

Ecogenomic signatures represent distinctive patterns in genetic sequences—from genes to entire genomes—that are diagnostic of an organism's or community's adaptation to specific environmental conditions or habitats. These signatures can be harnessed to trace environmental contamination, understand microbial niche specialization, and even guide drug discovery by revealing functional pathways activated under particular conditions. The validation of these signatures across diverse habitats represents a critical frontier in microbial ecology and environmental genomics, bridging the gap between nucleotide-level variation and ecosystem-level functions. This guide compares the experimental approaches, analytical frameworks, and applications of ecogenomic signatures, providing researchers with objective performance data to inform methodological selection.

The foundational principle of ecogenomic signatures rests on the premise that genomic composition reflects environmental selective pressures. For instance, bacteriophage genomes have been shown to encode clear habitat-associated signals diagnostic of their underlying microbial ecosystems. One seminal study demonstrated that the gut-associated phage ϕB124-14 encodes an ecogenomic signature that can successfully segregate metagenomes according to environmental origin and even distinguish 'contaminated' environmental metagenomes subject to simulated human fecal pollution from uncontaminated datasets [1] [2]. This indicates the substantial discriminatory power of phage-encoded ecological signals for biotechnological applications such as microbial source tracking (MST) tools for water quality monitoring.

Comparative Analysis of Ecogenomic Signature Approaches

The table below summarizes four prominent approaches to ecogenomic signature identification, their technical foundations, and their primary applications as revealed by current research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ecogenomic Signature Approaches

| Signature Type | Technical Foundation | Key Applications | Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage Habitat Signatures [1] [2] | Relative representation of phage-encoded gene homologues in metagenomes | Microbial source tracking, water quality assessment | Segregated metagenomes by environmental origin; identified human fecal contamination | Specificity to human gut vs. other mammalian guts requires refinement |

| Functional Trait Signatures (FRoGS) [3] | Deep learning model representing gene functions (GO annotations, expression profiles) | Drug target prediction, mechanism of action studies | Outperformed identity-based methods in detecting weak pathway signals (p<10⁻¹⁰⁰) | Requires extensive training data; computational intensity |

| Microbial Microdiversity Signatures [4] | Single copy core gene analysis (rpoC1), nutrient stress gene indicators | Phytoplankton ecology, biogeochemical cycling | Identified novel HLII-P haplotype adapted to low phosphorus conditions | Linking specific functions to microdiverse sub-clades remains challenging |

| CPR Lifestyle Signatures [5] | Metagenome-assembled genomes, genome streamlining metrics | Microbial interaction studies, evolutionary biology | Recovered 174 CPR MAGs; distinguished free-living vs. host-associated lineages | Cultivation difficulties hinder functional validation |

Experimental Protocols for Ecogenomic Signature Discovery

Protocol 1: Phage-Based Ecogenomic Signature Analysis

The detection of habitat-associated ecogenomic signatures in bacteriophage genomes follows a structured workflow that has proven effective for microbial source tracking applications [1] [2].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Phage Ecogenomic Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Phage Genomes | Source of target ORFs for analysis | ϕB124-14 (gut-associated), ϕSYN5 (marine), ϕKS10 (rhizosphere) |

| Viral Metagenomes | Habitat-specific viral community sequences | Human, porcine, bovine gut viromes; aquatic environmental viromes |

| Whole Community Metagenomes | Broader microbial community context | Human gut, other body sites, environmental habitats |

| Sequence Similarity Tools | Identification of homologues | BLAST, MMseq2 with e-value <1e⁻³, similarity >10% |

Methodology:

- Reference Genome Selection: Curate phage genomes with known habitat associations, such as the human gut-associated ϕB124-14, marine cyanophage ϕSYN5, and rhizosphere-associated ϕKS10 as phylogenetic controls [1].

- Metagenome Recruitment: Map quality-filtered metagenomic reads from target habitats against reference phage open reading frames (ORFs) using alignment tools (Bowtie2 with local alignment parameters: -D 15 -R 2 -L 15 -N 1 --gbar 1 --mp 3) [4].

- Abundance Calculation: Compute cumulative relative abundance of sequences similar to phage-encoded ORFs in each metagenome, normalized by metagenome size and sequencing depth [1].

- Habitat Discrimination: Statistically compare relative abundance profiles across habitats using ANOVA with post-hoc tests to identify signatures that significantly segregate metagenomes by environmental origin [1].

- Signature Validation: Apply signatures to 'contaminated' environmental metagenomes (through in silico fecal pollution simulation) to test discriminatory power for microbial source tracking [1] [2].

Protocol 2: Functional Representation of Gene Signatures (FRoGS)

The FRoGS approach addresses a critical limitation in conventional gene signature analysis by focusing on gene functions rather than identities, similar to how word2vec represents semantic meaning in natural language processing [3].

Methodology:

- Gene Functional Embedding: Train a deep learning model to map human genes into high-dimensional coordinates encoding their biological functions based on Gene Ontology (GO) annotations and experimental expression profiles from ARCHS4 [3].

- Signature Vector Generation: Aggregate vectors of individual gene members into a single signature vector representing the entire gene set, preserving functional information [3].

- Similarity Assessment: Implement a Siamese neural network to compute similarity between pairs of signature vectors representing different perturbations (e.g., compound treatment vs. genetic modulation) [3].

- Performance Validation: Test signature similarity detection against simulated gene sets with known pathway membership, comparing against traditional methods (Fisher's exact test) across varying signal strengths (λ = 5-25 pathway genes per signature) [3].

- Biological Application: Apply to drug target prediction using L1000 transcriptional profiles, where compound and genomic perturbations are represented by aggregated FRoGS signature vectors [3].

Table 3: Research Reagents for Functional Signature Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology Annotations | Source of functional gene relationships | GO biological processes, molecular functions, cellular components |

| Expression Databases | Empirical functional profiling | ARCHS4 database of gene expression profiles |

| Deep Learning Framework | Neural network training | Python/TensorFlow/PyTorch for embedding model |

| Signature Comparison Algorithm | Similarity quantification | Siamese neural network architecture |

Analytical Frameworks and Data Processing

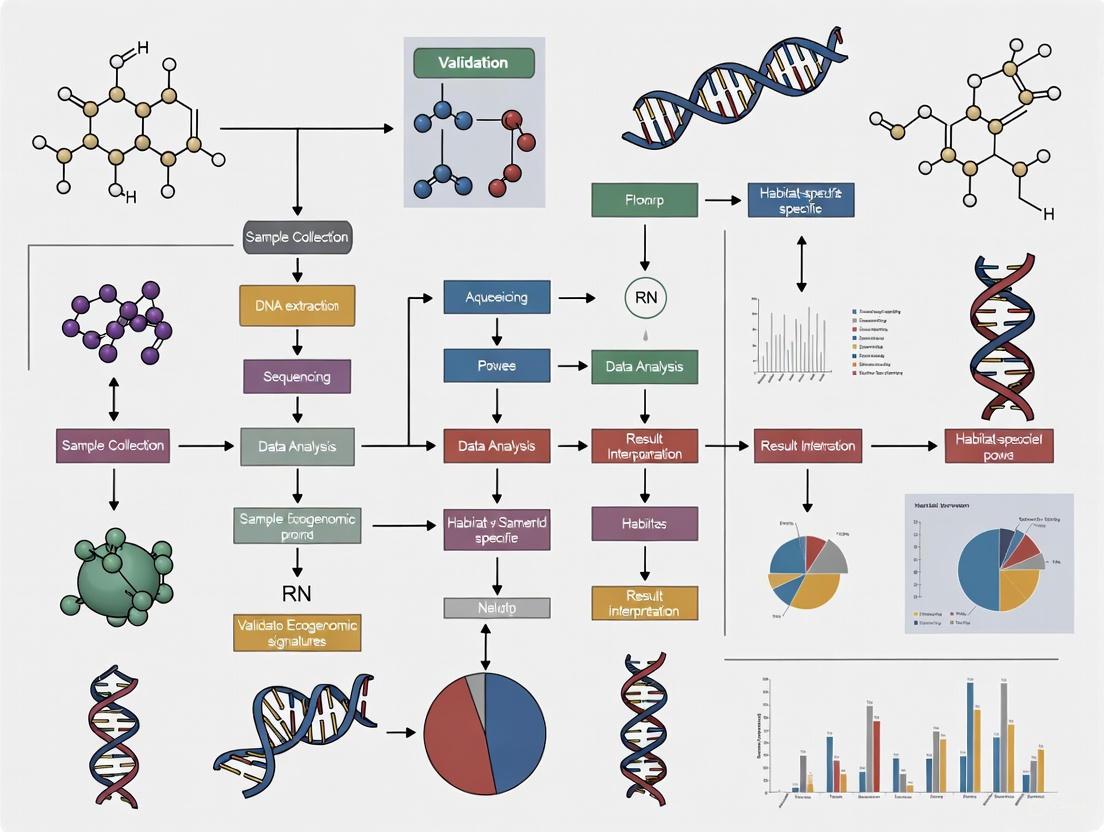

The reliable identification of ecogenomic signatures requires sophisticated analytical workflows that differ substantially across applications. The diagram below illustrates the contrasting approaches for phylogenetic versus functional signature discovery.

Habitat Correlation and Statistical Validation

Both phylogenetic and functional approaches require robust statistical frameworks to establish genuine habitat associations:

Environmental Metadata Integration: For microbial systems, this involves correlating genetic patterns with in situ measurements including temperature, nutrient concentrations (nitrogen, phosphorus, iron), and indicators of nutrient stress (e.g., Ω metrics for P-stress, N-stress, Fe-stress) [4].

Population Genomic Analysis: In eukaryotic systems like rotifers, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using genotyping by sequencing (GBS) can identify SNPs correlated with environmental predictability metrics. These analyses typically employ:

- Colwell's predictability metrics based on long-term environmental time series [6]

- Multivariate regression between allele frequencies and environmental variables [6]

- Functional annotation of significant SNPs to identify candidate genes [6]

Signature Validation: Cross-habitat testing is essential, such as applying human gut-derived phage signatures to bovine, porcine, and environmental metagenomes to test specificity [1]. Similarly, functional signatures should be validated against independent datasets to confirm their predictive power for habitat origin or biological activity [3].

Ecogenomic signatures represent a powerful framework linking genetic information to ecological adaptation. The comparative analysis presented here reveals that:

- Phage-based signatures offer exceptional discriminatory power for microbial source tracking in aquatic environments [1] [2]

- Functional signatures (FRoGS) significantly outperform traditional identity-based methods for detecting weak pathway signals, enabling more sensitive drug target prediction [3]

- Microdiversity signatures illuminate how subtle genetic variation drives niche partitioning in microbial systems [4]

- CPR reduced genomes provide signatures of host-associated lifestyles, expanding our understanding of microbial interactions [5]

The validation of these signatures across diverse habitats—from human guts to freshwater lakes to marine systems—underscores their robustness and promises to accelerate discoveries in environmental microbiology, ecosystem monitoring, and therapeutic development. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and analytical methods become more sophisticated, ecogenomic signatures will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in deciphering the genetic basis of ecological adaptation.

The transition of species into novel or changing habitats imposes unique selective pressures that drive rapid evolutionary changes at the genomic level. These adaptations, manifesting as molecular signatures within genomes, represent a fundamental record of how organisms persist in ecologically challenging settings [7]. From subterranean mammals to urban-dwelling songbirds and deep-sea urchins, habitat-driven evolution leaves distinctive marks on genomic architecture, gene families, and regulatory elements [8] [7] [9]. Understanding these genomic signatures provides crucial insights into evolutionary processes and offers potential applications in biotechnology, conservation, and medicine.

This guide compares genomic adaptation patterns across diverse habitats, synthesizing experimental data and methodologies from contemporary research. By examining how distinct environmental pressures—including depth, urbanization, aridity, and extreme substrates—shape genomic content through different molecular mechanisms, we provide a framework for validating ecogenomic signatures across habitats.

Comparative Analysis of Habitat-Driven Genomic Adaptations

Table 1: Genomic Adaptation Patterns Across Diverse Habitats

| Habitat Type | Organism | Key Genomic Changes | Primary Selective Forces | Experimental Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep-Sea vs. Shallow Water | Sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus vs. Allocentrotus fragilis) | Elevated dN/dS ratios in adult somatic tissue genes; Positive selection in skeletal development, endocytosis, sulfur metabolism genes [8] | Temperature, pressure, light, pH differences | Branch-site models; dN/dS calculation; Gene expression microarrays [8] |

| Urban vs. Rural | Great tit (Parus major) | Polygenic allele frequency shifts; Selective sweeps in neural function/development genes; Reduced gene flow between urban populations [9] | Noise, artificial light, pollution, altered food sources, habitat fragmentation [9] | Whole-genome resequencing (192 birds); LFMM/BayPass GEA; FST analysis; TreeMix [9] |

| Subterranean: Arid vs. Humid | Zokors (Myospalax aspalax vs. M. psilurus) | POS: DNA repair, hypoxia response, blood vessel development; REG: Visual perception, fructose metabolism; Large chromosomal inversions [7] | Darkness, hypoxia, limited food, water availability differences [7] | Branch-site models; Phylogenetic analysis; Hi-C for 3D genome architecture; Population resequencing [7] |

| Extreme Substrate (Stone) | Blastococcus species | Small core genome; Large accessory genome; Genomic plasticity; Substrate degradation, nutrient transport, stress tolerance genes [10] | Drought, salinity, alkalinity, heavy metals, radiation, nutrient scarcity [10] | Pangenome analysis (52 genomes); MicroTrait for ecological traits; CheckM genome quality assessment [10] |

| Plant-Associated vs. Other | Micromonospora bacteria | Distinct genomic clusters by environment; Plant colonization traits beyond standard PGP markers [11] | Host plant environment, root exudates, microbial competition [11] | Comparative genomics (74 strains); Novel bioinformatic pipeline for plant-related genes; Plant inoculation experiments [11] |

Table 2: Quantitative Genomic Metrics of Adaptation Across Studies

| Study System | Selection Metric | Value/Range | Genomic Features Analyzed | Statistical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea Urchins [8] | dN/dS ratio (adult somatic tissue) | Significantly higher than genome-wide average | 9,000+ GLEAN models; Tissue-specific gene sets | Branch-site models (PAML); Likelihood ratio tests |

| Great Tits [9] | Urban-associated SNPs | 2,758 SNPs (0.52% of dataset) FDR < 1% | 517,603 filtered SNPs; 314,351 LD-pruned SNPs | LFMM; BayPass; FST permutation tests |

| Zokors [7] | Positively Selected Genes (PSGs) | 436 PSGs in subterranean lineage | 5,178 high-confidence orthologous genes | Branch-site model; K2P value distribution analysis |

| Blastococcus [10] | Core vs. Accessory Genome | Small core, large accessory genome | 76 genomes (52 after quality control) | Pangenome analysis (Panaroo); OrthoFinder |

| Micromonospora [11] | Environment-specific clustering | High correlation with plant, soil, marine habitats | 74 bacterial proteomes; Plant-related gene database | HMMER annotation; EggNOG-mapper; UBCG phylogenomics |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Whole-Genome Scans for Selection

The detection of habitat-driven selection relies on sophisticated comparative genomic approaches. Branch-site models within the PAML (Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood) package test for positive selection affecting specific amino acid sites along particular lineages [8] [7]. This method compares likelihoods of models that allow or disallow sites with ω (dN/dS) > 1, using likelihood ratio tests to identify statistically significant positive selection [8]. For sea urchin studies, this approach revealed stronger signals of positive selection along the deep-sea (A. fragilis) branch compared to the shallow-water branch [8].

Population genomic analyses employ genotype-environment associations (GEAs) to detect loci underlying local adaptation. In great tit urban adaptation studies, Latent-Factor Mixed Models (LFMM) and BayPass algorithms identified SNPs whose allele frequencies correlate with urbanisation scores (PCurb) while accounting for population structure [9]. These methods effectively distinguish selective sweeps from demographic history by identifying loci with higher differentiation than expected under neutrality.

Figure 1: Genomic Selection Analysis Workflow. This pipeline integrates comparative and population genomic approaches to detect habitat-driven selection.

Pangenome Analysis for Microbial Adaptations

Microbial adaptations to extreme habitats are frequently analyzed through pangenome decomposition. The bacterial pangenome partitions genomic content into core genes (shared by all strains) and accessory genes (subset-specific), with the latter often encoding habitat-specific adaptations [10]. For Blastococcus species, researchers used Panaroo pipeline with a 95% sequence identity threshold to characterize pangenome structure, revealing extensive accessory genomes that confer resilience to stone-associated stressors [10].

Functional annotation pipelines like MicroTrait employ profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) to predict ecological traits from genomic sequences [10]. These methods utilize curated HMM profiles from databases such as Pfam, TIGRFAM, and dbCAN to map protein families to specific fitness traits, enabling systematic comparison of functional capabilities across lineages from different habitats.

Gene Expression Integration with Evolutionary Analysis

Integrative approaches combine evolutionary signatures with expression data to identify functionally relevant adaptations. In sea urchin studies, microarray-based expression profiling during different life-history stages and tissues revealed that genes expressed specifically in adult somatic tissues—which experience habitat differences most directly—show significantly higher evolutionary rates than those expressed in larvae, which share similar pelagic environments [8]. This expression-informed evolutionary analysis powerfully discriminates habitat-specific adaptations from general evolutionary processes.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms of Habitat Adaptation

DNA Repair and Hypoxia Response Pathways in Subterranean Adaptation

Subterranean habitats impose unique challenges including darkness, hypoxia, and elevated oxidative stress. Genomic analyses of zokors reveal strong positive selection in DNA repair pathways, including key canonical genes Atm (ataxia telangiectasia mutated), Atrip (ATR-interacting protein), and Mcm2 (minichromosome maintenance protein 2) [7]. These genes coordinate detection and repair of DNA damage, essential for maintaining genomic integrity under subterranean stress conditions.

Hypoxia response pathways show parallel adaptive changes, with selection observed in blood vessel development and hemopoiesis genes including Bmpr2 (bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II), Nox1 (NADPH oxidase 1), and Epor (erythropoietin receptor) [7]. These adaptations enhance oxygen delivery and utilization efficiency in oxygen-limited subterranean environments.

Figure 2: Subterranean Adaptation Pathways. Molecular networks responding to DNA damage and hypoxia in subterranean mammals.

Neural Development and Sensory Perception Pathways in Urban Adaptation

Urban environments create novel sensory landscapes characterized by noise, artificial light, and altered chemical cues. Genomic analyses of urban great tits reveal repeated selective sweeps in genes related to neural function and development [9]. These neural adaptations likely facilitate behavioral adjustments necessary for urban success, including altered communication, risk assessment, and foraging strategies.

Sensory perception pathways show contrasting adaptations depending on habitat demands. Subterranean zokors exhibit rapid evolution in visual perception genes including Gnat1, Gnat2, Gngt1, and crystallins (Cryba2, Crybb2, Crybb3, Crygs), reflecting visual system regression in dark environments [7]. Conversely, urban species may show sensory enhancements relevant to novel urban stimuli.

Ion Transport and Oxidative Stress Management in Saline and Aquatic Habitats

Salinity adaptation represents a recurring challenge across marine and terrestrial habitats. Comparative genomics of sea urchins reveals positive selection in genes involved in sulfur metabolism and skeletal development, reflecting mineralization differences between deep-sea and shallow-water environments [8]. Similarly, halophilic plants and microbes show adaptations in ion transport systems including Na+/H+ transporters and H+-ATPases that maintain ionic balance under high salinity [12].

Oxidative stress management represents a universal adaptive mechanism across habitats. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) genes show evolutionary changes in both saline-adapted plants and stone-dwelling Blastococcus [12] [10]. These enzymes mitigate reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by various environmental stressors, including high salinity, heavy metals, and radiation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ecogenomic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System [13] | Targeted gene knockout | Validating mutational signatures in isogenic cell lines (e.g., HAP1) | Haploid lines simplify knockout generation; Confirm loss of protein expression via immunoblotting |

| PAML Package [8] [7] | Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood | dN/dS calculation; Branch-site tests for positive selection | Uses codon-based alignment; Likelihood ratio tests for statistical significance |

| CheckM [10] | Assess genome quality and contamination | Microbial genome quality control (completeness ≥70%, contamination ≤7.0%) | Relies on conserved single-copy marker genes; Essential for comparative genomics |

| Panaroo [10] | Pangenome graph analysis | Identifying core and accessory genomes across strains | Adjustable identity thresholds (typically 95%); Handles population-level variation |

| OrthoFinder [10] | Orthogroup inference from genomic data | Identifying single-copy orthologous genes for comparative analysis | Resolves evolutionary relationships between genes across species |

| MicroTrait [10] | Ecological trait prediction from genomes | Predicting substrate degradation, stress tolerance, nutrient transport | Uses HMM profiles; Integrates multiple functional databases |

| Global Ocean Sampling (GOS) Dataset [14] | Marine metagenomic reference | Ecogenomic context for marine phage distribution | Provides environmental contextual data for sequence matches |

The comparative analysis of habitat-driven genomic adaptations reveals both universal principles and habitat-specific mechanisms. While the molecular players differ—ion transporters in saline habitats, DNA repair genes in subterranean species, neural genes in urban adapters—common evolutionary patterns emerge across diverse systems. These include repeated recruitment of similar functional gene categories, prevalent polygenic adaptation supplemented by selective sweeps, and frequent structural genomic changes facilitating adaptive divergence.

Experimental validation remains crucial for distinguishing true adaptations from genomic noise. Isogenic cell models [13], functional assays [11], and integrative multi-omics approaches provide essential validation of ecogenomic predictions. The continued development of genome-editing technologies, particularly CRISPR-Cas9 systems, promises to accelerate functional validation of habitat-associated genomic signatures across diverse organisms and ecosystems.

Future research directions should prioritize multi-habitat comparisons within unified phylogenetic frameworks, expanded integration of epigenomic and 3D genomic data, and development of standardized ecogenomic pipelines that enable direct comparison of adaptation patterns across the tree of life. Such approaches will further illuminate how habitat—as a fundamental evolutionary driver—shapes genomic content across biological scales.

The validation of ecogenomic signatures—distinct genetic patterns that are diagnostic of specific habitats—is a cornerstone of modern microbial ecology. These signatures allow researchers to trace microbial and viral genetic material back to their original environments, with profound implications for public health, environmental monitoring, and therapeutic development [1]. This case study examines the bacteriophage ϕB124-14 as a model system for discovering and validating a human gut-associated ecogenomic signature. Through a series of comparative genomic and metagenomic investigations, researchers have demonstrated that this phage encodes a clear habitat-related signal, providing a template for how such signatures can be isolated and authenticated across diverse microbial habitats [1].

ϕB124-14: A Model Human Gut Bacteriophage

Origin and Basic Characteristics

Phage ϕB124-14 is a bacteriophage that infects specific strains of Bacteroides fragilis, a prominent member of the human gut microbiome. It was originally isolated from municipal wastewater and has been consistently detected in human faecal samples while being absent from faecal samples from a wide range of domestic and wild animals, suggesting a human gut-specific nature [15] [16]. Morphologically, ϕB124-14 belongs to the Caudovirales order and Siphoviridae family, featuring a binary structure with an icosahedral head (approximately 49.8 nm in diameter) and a non-contractile tail (about 162 nm in length) [15] [16].

Genomic Features

The ϕB124-14 genome is a circular, double-stranded DNA molecule of 47,159 base pairs, encoding 68 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) with non-coding sequences limited to only 8.2% of the genome [17]. Comparative genomic analyses revealed its closest relative is ϕB40-8, another Bacteroides phage, though significant genomic differences exist [15].

Restricted Host Range

A defining characteristic of ϕB124-14 is its highly restricted host range. Experimental studies demonstrate it infects only a subset of closely related B. fragilis strains, primarily those isolated from the same municipal wastewater source and the reference strain DSM 1396 originally from human pleural fluid [15]. It shows no infectivity against other Bacteroides species or geographically distinct B. fragilis strains, indicating extreme niche specialization [15].

Experimental Validation of the Ecogenomic Signature

Core Methodology: Metagenomic Profiling

The principal approach for identifying and validating the habitat-specific signature of ϕB124-14 involved comparative metagenomic analysis across diverse habitats. The foundational methodology can be summarized in the following workflow:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for ecogenomic signature validation, showing the process from sample collection to signature identification.

The experimental protocol involves:

Sample Collection and Preparation: Metagenomic datasets are compiled from target (human gut) and non-target (other body sites, animal guts, environmental) habitats. These include both viral-like particle (VLP)-enriched viromes and whole-community metagenomes [1].

Sequence Data Processing: Quality control, assembly, and annotation of metagenomic sequences are performed using standard bioinformatic pipelines [18].

Reference-Based Profiling: The complete genome sequence of ϕB124-14 serves as a reference. Translated open reading frames (ORFs) from the phage genome are used as queries against metagenomic datasets [1].

Quantitative Assessment: The cumulative relative abundance of sequences with significant similarity to ϕB124-14 ORFs is calculated for each habitat. This metric represents the density of the phage's genetic signature across different environments [1].

Comparative Analysis: The representation of ϕB124-14 sequences is compared against control phages from non-gut habitats (e.g., marine Cyanophage SYN5, rhizosphere-associated Burkholderia prophage KS10) to establish habitat specificity [1].

Key Findings: Signature Validation Across Habitats

The ecogenomic profiling of ϕB124-14 consistently demonstrated a strong human gut-associated signal, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Ecogenomic profiling of ϕB124-14 across different habitat types based on metagenomic analysis [1].

| Habitat Type | Sample Type | Relative Representation of ϕB124-14 Signature | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gut | Viral Metagenomes (Viromes) | Significantly enriched | p < 0.05 vs. environmental habitats |

| Human Gut | Whole Community Metagenomes | Enriched (vs. other body sites) | p < 0.05 vs. other human body sites |

| Other Mammalian Guts (Porcine, Bovine) | Viral Metagenomes | Moderate representation | Not significant vs. human gut |

| Environmental (Marine, Freshwater) | Viral Metagenomes | Low representation | p < 0.05 vs. human gut |

| Other Human Body Sites | Whole Community Metagenomes | Low representation | p < 0.05 vs. human gut |

Analysis of viral metagenomes revealed a significantly greater mean relative abundance of ϕB124-14-encoded ORFs in human gut viromes compared to environmental datasets [1]. When compared to control phages, ϕB124-14 displayed a distinct gut-associated enrichment pattern not observed in phages from other habitats. Cyanophage SYN5, for instance, showed significantly greater representation in marine environments, while ϕB124-14 showed significantly greater representation in human-derived datasets [1].

This ecogenomic signature proved sufficiently discriminatory to distinguish 'contaminated' environmental metagenomes (subject to simulated in silico human faecal pollution) from uncontaminated datasets, highlighting its potential application in source tracking [1].

Technological Applications: From Signature to Tools

Development of Quantitative Molecular Assays

The validated ecogenomic signature of ϕB124-14 provided the foundation for developing culture-independent microbial source tracking (MST) tools. Researchers employed a "biased genome shotgun strategy" to identify human sewage-associated genetic regions within the ϕB124-14 genome [17]. This process involved:

- Target Identification: Screening 12,026 bp (25.6%) of the ϕB124-14 genome to identify genetic regions with strong human faecal association [17].

- Primer Design: Designing PCR primers for regions amenable to amplification while meeting standard design parameters [17].

- Assay Validation: Testing candidate assays against a panel of 100 individual faecal samples from diverse animal species to evaluate specificity and sensitivity [17].

Table 2: Performance comparison of ϕB124-14 bacteriophage-like qPCR assays against other human-associated fecal source identification methods [17].

| Methodology | Target Type | Specificity | Sensitivity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ϕB124-14 Bacteriophage-like qPCR | Viral | Superior | High | Developed from ecogenomic signature |

| HF183/BacR287 qPCR | Bacterial (Bacteroides) | Lower than ϕB124-14 | Comparable | Widely used but less specific |

| HumM2 qPCR | Bacterial (Bacteroides) | Lower than ϕB124-14 | Comparable | – |

| crAssphage CPQ056 & CPQ064 | Viral | Lower than ϕB124-14 | High | More recently discovered target |

| Culture-Based GB-124 | Bacteriophage (Host) | High | Variable | Requires cultivation, longer turnaround |

The resulting ϕB124-14 bacteriophage-like qPCR assays demonstrated superior specificity compared to top-performing DNA-based bacterial and viral human-associated methods, with strong correlation to culture-based GB-124 measurements in sewage influent [17].

Genome Signature-Based Sequence Recovery

Beyond targeted PCR assays, the ϕB124-14 ecogenomic signature enabled the development of advanced bioinformatic approaches for mining metagenomic data. The Phage Genome Signature-Based Recovery (PGSR) strategy exploits similarities in global nucleotide usage patterns (tetranucleotide usage profiles) between phage infecting related host species [18].

This approach allowed researchers to interrogate conventional whole-community metagenomes and recover "subliminal" phage sequences with high fidelity—sequences that were poorly represented in VLP-derived viral metagenomes and often missed by conventional alignment-driven methods [18]. When applied to human gut metagenomes, this strategy successfully recovered 85 metagenomic fragments classified as phage, with sizes ranging from 10-63.7 kb, 16 of which represented near full-length or complete phage genomes [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for ecogenomic signature research, as derived from the ϕB124-14 case study.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Phage Genomes | Baseline for comparative genomics and metagenomic profiling | ϕB124-14 (complete genome), ϕB40-8, Cyanophage SYN5, Burkholderia prophage KS10 [15] [1] |

| Host Bacterial Strains | Phage propagation, host range determination, assay development | Bacteroides fragilis GB-124, other B. fragilis strains for host specificity testing [15] [19] |

| Metagenomic Datasets | Ecological profiling, signature validation across habitats | Human gut viromes, whole community gut metagenomes, environmental viromes [1] [18] |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Sequence analysis, signature identification, phylogenetic placement | Tetranucleotide usage profiling, ORF similarity analysis, genome signature-based recovery tools [1] [18] |

| PCR/Primer Design Tools | Development of culture-independent detection assays | "Biased genome shotgun" approach for primer design targeting human-associated genetic regions [17] |

The case study of phage ϕB124-14 provides a comprehensive framework for validating ecogenomic signatures across habitats. Through a multi-faceted approach combining comparative genomics, metagenomic profiling, and experimental validation, researchers established that individual phage can encode discernible habitat-associated signals diagnostic of underlying microbiomes [1]. The successful translation of this ecogenomic signature into specific, sensitive molecular tools for microbial source tracking [17] demonstrates the practical utility of such fundamental ecological research. Furthermore, the genome signature-based approaches developed through this work [18] offer powerful methods for accessing the considerable "biological dark matter" within microbial viromes, promising new insights into the structure and function of complex microbial ecosystems across diverse habitats.

The genus Novosphingobium, a member of the Sphingomonadaceae family, represents a group of metabolically versatile Alphaproteobacteria with a remarkable ability to inhabit diverse ecological niches. These microorganisms have been isolated from environments ranging from rhizosphere soil and plant surfaces to heavily contaminated soils, and marine and freshwater ecosystems [20]. Their metabolic plasticity and adaptability make them key players in nutrient cycling and bioremediation. A growing body of genomic evidence suggests that the phylogenetic relationships between Novosphingobium strains are less indicative of functional genotype similarity than the selective pressures of their specific habitats [20]. This article examines the habitat-specific gene enrichment patterns in Novosphingobium strains, validating the concept that ecogenomic signatures are profoundly shaped by environmental parameters, with significant implications for microbial ecology and applied biotechnology.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of Habitat-Specific Traits

Comparative genomic studies of diverse Novosphingobium strains have revealed that genome size, coding potential, and functional gene content vary significantly across different habitats, underscoring a high degree of genomic plasticity [20]. The table below summarizes key genomic features and habitat-specific metabolic traits identified in Novosphingobium.

Table 1: Genomic Features and Habitat-Specific Metabolic Traits of Novosphingobium

| Habitat | Representative Strains | Genome Size (bp) | Key Habitat-Specific Genes/Features | Bioremediation Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizosphere | Novosphingobium sp. P6W, N. rosa NBRC 15208 | 6,537,300 - 6,952,763 | Alkane sulfonate (ssuABCD) assimilation [20] | Plant growth promotion [21] |

| Contaminated Soil | N. barchamii LL02, N. lindaniclasticum LE124 | 4,857,928 - 5,307,348 | Ectoine biosynthesis genes; wide variety of mono- and dioxygenases [20] | Degradation of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) [20] [22] [23] |

| Marine Water | Novosphingobium sp. PP1Y, N. pentaromaticivorans US6-1 | 5,313,905 - 5,457,578 | Habitat-specific β-barrel outer membrane protein hubs (e.g., PP1Y_AT17644) [20] | Degradation of aromatic compounds at oil-water interfaces [20] [21] |

| Freshwater | Novosphingobium sp. THN1, AAP1 | 4,232,088 - 4,750,579 | Habitat-specific β-barrel outer membrane protein hubs (e.g., Saro_1868) [20] | Microcystin degradation (mlr gene cluster) [21] |

Analysis of core genomes has demonstrated that the enrichment of specific gene sets is a response to microenvironmental conditions. For instance, while certain traits like ectoine biosynthesis were initially assumed to be marine-specific, their presence in isolates from contaminated soil reveals a broader relevance in osmolytic regulation [20]. Furthermore, sulfur acquisition and metabolism are the only core genomic traits that differ significantly in proportion between ecological groups, with alkane sulfonate assimilation being exclusive to rhizospheric isolates [20].

Table 2: Key Enzymes and Metabolic Pathways in Novosphingobium Bioremediation

| Enzyme Class | Specific Enzymes | Target Substrates | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mono- and Dioxygenases | PAH hydroxylating dioxygenase (PahAB) [23] | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) such as phenanthrene, pyrene [23] | Initial oxidation of aromatic rings, broad substrate specificity [20] [23] |

| Dehydrohalogenases | LinA variants [24] | Hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) isomers [24] | Dechlorination of persistent organic pollutants [24] |

| Haloalkane Dehalogenases | LinB [24] | β-hexachlorocyclohexane (β-HCH) [24] | Hydrolytic dehalogenation in HCH degradation pathway [24] |

| Microcystinase | MlrA [21] | Microcystin-LR (MC-LR) [21] | Hydrolyzes cyclic microcystin to a linear intermediate [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Uncovering Habitat-Specific Signatures

The identification of habitat-specific genes and regulatory hubs in Novosphingobium relies on a suite of advanced genomic and metagenomic techniques. The following workflow visualizes a generalized protocol for such ecogenomic studies.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Identifying Habitat-Specific Genomic Signatures

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Strain Selection and Genome Sequencing: The process begins with the selection of multiple Novosphingobium strains isolated from well-defined habitats such as rhizosphere soil, contaminated sites, and marine and freshwater environments [20]. High-quality genomic DNA is extracted from pure cultures. Sequencing can be performed using platforms like the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RSII system for long-read sequencing, which is advantageous for assembling complete genomes and plasmids [21]. For a culture-independent approach, shotgun metagenomic sequencing of environmental samples on an Illumina NextSeq 550 system is employed [25].

Genome Assembly and Annotation: For pure cultures, sequence assembly is conducted using specialized pipelines such as the SMRT Analysis pipeline in conjunction with the HGAP assembler [21]. For complex environmental samples, metaSPAdes is used for de novo assembly of metagenomic sequences [25]. The assembled contigs are then binned to reconstruct Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). Gene prediction is performed using tools like Prodigal, followed by functional annotation against databases including NCBI NR, COG, KEGG, and Swiss-Prot to assign putative functions to coding sequences [21].

Pangenome and Comparative Analysis: The pangenome, comprising the core genome (genes shared by all strains) and the flexible genome (genes present in a subset), is constructed [20] [21]. Orthologous protein analysis helps identify the core gene set. Comparative genomic analysis then focuses on identifying genes that are uniquely enriched or present in strains from a particular habitat. This includes analyzing genomic islands, which are often associated with niche adaptation, and profiling specific metabolic pathways, such as those for sulfur acquisition or aromatic compound degradation [20].

Identification of Regulatory Hubs and Validation: Protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis can be conducted in silico to identify key proteins that act as hubs within metabolic networks. In Novosphingobium, this approach has revealed habitat-specific β-barrel outer membrane proteins as potential key hubs in different environments [20]. For catabolic pathways, regulator genes (e.g., pahR for PAH degradation) can be identified, and their function validated through the construction of reporter gene-based biosensors to confirm inducibility by specific substrates [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details essential materials and tools derived from the cited research, which are crucial for conducting ecogenomic and functional studies on Novosphingobium.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Novosphingobium Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| M9 Minimal Medium | Defined medium for bacterial growth with specific carbon sources. | Culturing Novosphingobium with PAHs or other xenobiotics as sole carbon source to study degradation pathways [23]. |

| Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | Extraction of high-quality environmental DNA (eDNA) from complex samples like soil and sediments. | Preparing DNA for shotgun metagenomic sequencing of mangrove or contaminated soil ecosystems [25] [26]. |

| KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Roche) | Library preparation for next-generation sequencing. | Constructing sequencing libraries from eDNA for Illumina platforms [25]. |

| metaSPAdes Assembler | De novo assembly of metagenomic sequencing reads. | Reconstructing microbial genomes directly from environmental samples without cultivation [25]. |

| Prodigal Software | Prediction of protein-coding genes in genomic and metagenomic sequences. | Annotating open reading frames in assembled Novosphingobium genomes [21]. |

| pKSPA-R Plasmid | Biosensor construct with a reporter gene under the control of a PAH-inducible promoter. | Detecting low concentrations (as low as 4 ppb) of PAHs in water samples [23]. |

| LinA & LinB Enzymes | Recombinant dehydrohalogenase and haloalkane dehalogenase. | Enzymatic bioremediation studies for degrading HCH isomers, including refolding protocols for inclusion bodies [24]. |

The compelling evidence from comparative genomic studies firmly establishes that Novosphingobium strains possess highly plastic genomes, which are dynamically shaped by their environmental niches. The enrichment of specific metabolic traits—such as sulfur assimilation in rhizosphere isolates, diverse oxygenases in contaminated soil strains, and unique outer membrane protein hubs across all habitats—provides a robust validation of ecogenomic signature theory. These habitat-specific genetic repertoires not only determine the organism's functional role in its ecosystem but also present a treasure trove of biocatalytic potential. For researchers in drug development and environmental biotechnology, understanding these patterns is pivotal for harnessing Novosphingobium and similar microbes for targeted applications, from designing precise bioremediation strategies to discovering novel, stable enzymes for industrial processes.

The genomic architecture of prokaryotes is characterized by a mosaic of core and accessory elements, each playing a distinct role in evolutionary adaptation and ecological resilience. The core genome, comprising genes shared by all strains of a species, encodes essential housekeeping functions central to basic cellular processes [27] [28]. In contrast, the accessory genome consists of genes present in only a subset of strains, providing niche-specific adaptations that enable survival in diverse environments [29] [30]. Understanding the relative stability and evolutionary dynamics of these genomic components across different ecosystems is fundamental to deciphering microbial evolution, pathogenesis, and environmental adaptation. This comparison guide objectively analyzes the stability characteristics of core genomic features versus accessory genes, synthesizing experimental data from recent genomic studies to validate ecogenomic signatures across habitats.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Core Genome Characteristics

The core genome represents the genetic backbone of a species, maintained across all members through evolutionary time. These genes typically include essential metabolic pathways, transcription and translation machinery, and DNA replication mechanisms [28] [31]. Core genes are generally subject to strong purifying selection that removes deleterious mutations, maintaining functional integrity across generations [27] [32]. In Enterococcus faecium, for instance, functional analysis of core genes revealed predominant roles in growth, DNA replication, transcription, translation, carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, stress response, and transporters [31]. The stability of these genes provides phylogenetic signals for reconstructing evolutionary relationships among bacterial strains [30].

Accessory Genome Characteristics

The accessory genome, sometimes called the "flexible" genome, consists of genes acquired through horizontal gene transfer or lost through deletion events [29] [30]. This genomic compartment includes plasmids, phages, genomic islands, and other mobile genetic elements that confer context-dependent advantages [30] [31]. Accessory genes often encode functions related to environmental sensing, nutrient acquisition, stress tolerance, and host interaction [33] [10]. In the Bacillus cereus group, accessory genes contribute significantly to ecological divergence between clades, with different gene functions enriched in different clades [32].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Core and Accessory Genomes

| Feature | Core Genome | Accessory Genome |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Genes shared by all strains of a species | Genes present in a subset of strains |

| Evolutionary Rate | Generally slower due to purifying selection | Generally faster due to diversifying selection |

| Primary Maintenance Mechanism | Vertical inheritance | Horizontal gene transfer |

| Typical Functions | Essential housekeeping functions | Niche-specific adaptations |

| Impact of Mutation | Often deleterious | Potentially adaptive |

Quantitative Comparative Analysis of Genomic Stability

Mutation and Recombination Rates

Comparative genomic studies across multiple bacterial species reveal distinct patterns of mutation and recombination between core and accessory genomes. Research on Streptococcus pneumoniae employing the mcorr method—a coalescent-based population genetics approach that analyzes correlated substitutions—found that core genes often have higher recombination rates than accessory genes [27]. This finding challenges conventional assumptions that accessory genomes experience more frequent recombination. The same study reported that while recombination rates were higher in core genomes, mutational divergence was lower, suggesting that divergence-based homologous recombination barriers could contribute to differences in recombination rates between genomic compartments [27].

Selection Pressures Across Ecosystems

Different selection pressures act on core and accessory genomes, driving distinct evolutionary patterns:

Purifying selection is prevalent in core genomes, removing deleterious alleles that impair essential cellular functions [32]. This conservative pressure maintains functional integrity across environments.

Diversifying selection more frequently affects accessory genes, promoting genetic variation that facilitates adaptation to specific ecological niches [32]. In the Bacillus cereus group, genes under diversifying selection show signs of frequent horizontal gene transfer, promoting diversification between clades [32].

Ecological determinants shape accessory genome content, with different bacterial clades maintaining distinct repertoires of accessory genes optimized for their specific habitats [32] [10]. For instance, Blastococcus species isolated from extreme environments possess accessory genes enhancing heavy metal resistance and pollutant degradation [10].

Table 2: Selection Pressures on Core vs. Accessory Genomes in Different Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | Core Genome Selection | Accessory Genome Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Host-associated (e.g., E. coli ST131) | Strong purifying selection maintaining basic cellular functions | Diversifying selection for host-specific adaptations (e.g., virulence factors) |

| Extreme environments (e.g., Blastococcus in stone niches) | Conservation of essential metabolic pathways | Positive selection for stress response genes (e.g., heavy metal resistance) |

| Generalist species (e.g., Bacillus cereus group) | Stable across clades with minimal functional variation | Clade-specific enrichment for niche adaptation |

Experimental Approaches for Assessing Genomic Stability

Genomic Stability Assessment Protocols

Research into core and accessory genome stability employs several established methodological frameworks:

Backbone Stability (BS) Analysis quantifies the conservation of core gene order between genomes. The BS coefficient between genome i and genome j is defined as: BSij = Nijcn / Nijtot, where Nijcn is the number of conserved edges and Nijtot is the total edges (conserved + non-conserved) in the comparison [29]. This approach measures how conserved the core gene order is between strains, with values approaching 1 indicating highly similar organization.

Genome Organization Stability (GOS) Analysis integrates both genome rearrangements and the effect of gene insertions/deletions: GOSij = Nijcn / (Nijcc + Nijac/2), where Nijcc represents edges connecting core genes and Nij_ac represents edges between core and accessory genes [29]. This method accounts for neighborhoods broken by insertion/deletion of accessory genes, providing a more comprehensive stability assessment.

Pan-genome Analysis involves clustering all genes from multiple genomes into orthology groups, typically using tools like Roary or Panaroo with sequence identity thresholds (e.g., ≥90-95% identity and coverage) [28] [10]. This approach discriminates between core genes (shared by all isolates) and accessory genes (subset-specific), enabling quantitative comparison of their evolutionary dynamics.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comparative analysis of core and accessory genome stability, integrating multiple bioinformatics approaches.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Genomic Stability Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Roary [33] [31] | Pan-genome pipeline | Rapid large-scale pan-genome analysis, identifies core and accessory genes |

| Panaroo [10] | Pan-genome analysis with graph-based approach | Identifies core/accessory genes, handles assembly errors |

| OrthoFinder [10] | Orthogroup inference | Identifies groups of orthologous genes across multiple genomes |

| IQ-TREE [33] [10] | Phylogenetic inference | Constructs maximum likelihood trees from core gene alignments |

| CheckM [28] [10] | Genome quality assessment | Evaluates completeness and contamination of genomes pre-analysis |

| mcorr [27] | Correlated substitution analysis | Infers homologous recombination parameters without phylogenetic reconstruction |

| fastANI [10] | Average Nucleotide Identity | Calculates genomic similarity for species demarcation |

Ecological Determinants of Genomic Stability

Habitat-Specific Evolutionary Pressures

Environmental characteristics exert distinct selective pressures that shape the stability of core and accessory genomes differently:

In extreme environments characterized by desiccation, salinity, alkalinity, and heavy metal contamination (e.g., stone-dwelling Blastococcus habitats), microorganisms exhibit highly dynamic genetic composition with a small core genome and large accessory genome, indicating significant genomic plasticity [10]. This configuration enables rapid adaptation to fluctuating conditions while maintaining essential functions.

For host-associated bacteria like E. coli ST131, which moves frequently between human, avian, and domesticated animal hosts, the core genome remains stable across hosts, while the accessory genome differentiates into distinct clusters associated with specific resistance genes (e.g., CTX-M type) [30]. This pattern demonstrates how conserved core genomes facilitate host generality, while flexible accessory genomes enable host-specific adaptations.

In pathogenic species like Streptococcus pneumoniae, core genes experience higher recombination rates than accessory genes, potentially increasing the efficiency of selection in conserved genomic regions [27]. This contrasts with traditional models suggesting that accessory genomes evolve more rapidly through recombination.

Ecogenomic Signatures Across Taxonomic Groups

Different bacterial taxa exhibit distinctive patterns of core and accessory genome evolution:

Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli, Salmonella): These species typically display open pan-genomes where the accessory genome continuously expands as new strains are sequenced [28]. The core genome represents a relatively small fraction (often <50%) of the total gene pool, with substantial accessory genomes facilitating ecological flexibility.

Actinobacteria (Blastococcus, Modestobacter): Species from extreme environments show remarkable genomic plasticity, with accessory genomes enriched in genes for substrate degradation, nutrient transport, and stress tolerance [10]. The core genome remains highly conserved, maintaining essential functions across niches.

Firmicutes (Bacillus cereus group, Enterococcus faecium): These groups demonstrate clade-specific selection patterns, where different gene functions are enriched in different clades for both core and accessory genomes [31] [32]. This facilitates ecological divergence while maintaining phylogenetic coherence.

Figure 2: Ecological determinants shaping core and accessory genome evolution across different habitat types.

The comparative analysis of core genomic features and accessory genes reveals a fundamental paradigm in microbial evolution: core genomes provide phylogenetic stability through strong purifying selection and conserved gene order, while accessory genomes facilitate ecological adaptability through dynamic gene content and higher evolutionary plasticity. Quantitative assessments across diverse ecosystems demonstrate that core genes can experience substantial recombination—sometimes at higher rates than accessory genes—but maintain lower mutational divergence overall [27].

These patterns of genomic stability have profound implications for ecogenomic signature validation. The conservation of core genes across environments provides reliable markers for phylogenetic reconstruction and species demarcation, while the flexible nature of accessory genomes enables fine-scale adaptation to specific ecological niches [32] [10]. This dual evolutionary strategy—maintaining a stable functional core while permitting peripheral innovation—represents a highly successful evolutionary strategy across microbial taxa.

For researchers investigating bacterial pathogenesis, environmental adaptation, or evolutionary dynamics, these findings underscore the necessity of integrated approaches that examine both core and accessory genomic components [30]. Future studies leveraging expanding genomic datasets and refined analytical methods will continue to enhance our understanding of how genomic stability patterns shape microbial diversity across Earth's ecosystems.

Advanced Computational Methods for Ecogenomic Signature Detection and Application

Chaos Game Representations (CGR) and k-mer Frequency Analysis

Within the field of ecogenomics, the validation of signatures across diverse habitats depends on robust methods to compare genetic sequences efficiently. Alignment-free sequence comparison techniques have become essential for processing the vast volumes of data generated by modern sequencing technologies, avoiding the computational bottlenecks of traditional alignment-based methods [34] [35]. Among these, Chaos Game Representation (CGR) and k-mer Frequency Analysis are two pivotal approaches. CGR translates sequences into a graphical, coordinate-based format, capturing complex patterns in a visual and mathematical form [36] [37]. In parallel, k-mer analysis breaks down sequences into short substrings of length k, using their statistical distribution to infer sequence characteristics and relationships [34]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two methodologies, detailing their principles, experimental protocols, and performance to inform their application in ecogenomic signature research.

Comparative Analysis: Core Principles and Ecogenomic Applications

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics and habitat-related applications of CGR and k-mer analysis.

Table 1: Core Principles and Ecogenomic Applications of CGR and K-mer Analysis

| Feature | Chaos Game Representation (CGR) | K-mer Frequency Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Iterative mapping of sequences into a coordinate space (e.g., 2D or 3D square) [36] [38]. | Enumeration of all contiguous subsequences of length k within a sequence [34]. |

| Primary Output | An image or a trajectory of points in a fractal pattern [37]. | A frequency vector of all possible k-mers [34] [39]. |

| Sequence Information Encoded | Markov Properties: Reveals higher-order statistical patterns and dependencies between nucleotides [36]. | Compositional Features: Captures the frequency and, in some advanced methods, the position distribution of k-mers [39] [35]. |

| Key Ecogenomic Applications | - Phylogenetic Analysis: Unique genomic signatures aid in constructing evolutionary trees [36] [38].- Pattern Visualization: Identifying and visualizing repetitive elements and compositional biases in metagenomic sequences [37]. | - Taxonomic Classification & Metagenomics: Rapid assignment of sequences to taxonomic groups in diverse environmental samples [34].- Biomarker Discovery: Identifying unique k-mers (e.g., nullomers) as signatures for specific organisms or environmental adaptations [34] [40]. |

Performance and Experimental Data

When deployed for specific bioinformatics tasks, the two methods exhibit distinct performance characteristics, strengths, and limitations, as detailed in the following table.

Table 2: Experimental Performance and Practical Considerations

| Aspect | Chaos Game Representation (CGR) | K-mer Frequency Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Handling of Unequal Sequence Lengths | Frequency Chaos Game Representation (FCGR) transforms sequences into equal-sized matrices by counting k-mer frequencies in a grid, facilitating comparison [36]. | Inherently handles sequences of different lengths by working with frequency vectors, though longer k-values can lead to sparse data [34]. |

| Computational Efficiency | The CGR algorithm itself is iterative and computationally light. However, global similarity comparison of entire trajectories can be complex [38]. | Highly efficient and scalable for large datasets, with numerous optimized algorithms available for k-mer counting [34] [35]. |

| Sensitivity to Mutations | Substitutions: Alter the trajectory path, changing point positions [38].Insertions/Deletions: Change the total number of points in the trajectory, affecting the overall shape [38]. | Substitutions: Directly alter the k-mers at the mutation site.Insertions/Deletions: Cause a frame-shift in all subsequent k-mers, leading to a larger change in the k-mer profile [34]. |

| Reported Performance | A 3D CGR method using shape signatures was shown to produce phylogenetic trees comparable to alignment-based methods and was robust to different mutation types [38]. | Methods like IEPWRMkmer, which combine k-mer frequency and position information, have demonstrated high efficiency and reliability in phylogenetic tree reconstruction, as validated by Robinson-Foulds distance metrics [39]. |

| Key Limitations | Traditional 2D CGR point-by-point distance can be biased by the spatial arrangement of nucleotides, which may not reflect true biological divergence [38]. | The choice of k is critical; short k can lack specificity, while long k leads to computational overhead and data sparsity (overfitting) [34]. |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for K-mer Frequency Analysis in Metagenomic Classification

A typical workflow for using k-mer analysis in an ecogenomic context, such as classifying sequences in a metagenomic sample, involves the following steps. This protocol is widely used in tools for taxonomic classification and signature discovery [34] [40].

Title: K-mer Analysis Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Input Sequence Data: Gather whole genome or metagenomic sequencing reads from environmental samples (e.g., soil, water) [35].

- Sequence Fragmentation: If working with whole genomes, they may be computationally fragmented into reads to standardize analysis.

- K-mer Generation: Select a value for k (e.g., k=9 to k=31 is common). Slide a window of length k across each sequence, extracting every possible k-mer [34]. The choice of k is a critical parameter that balances specificity and computational load.

- K-mer Counting & Frequency Vector Creation: For each sequence, count the occurrence of each possible k-mer. This generates a high-dimensional frequency vector representing that sequence [34] [39].

- Dimensionality Reduction (Optional but common): Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project the high-dimensional k-mer vectors into a 2D or 3D space to visualize sequence relationships and identify clusters [35].

- Dissimilarity Matrix Calculation: Calculate pairwise distances between sequences based on their k-mer frequency vectors. Common distance measures include Manhattan or Euclidean distance [39].

- Downstream Analysis: Use the dissimilarity matrix for tasks such as phylogenetic tree construction, taxonomic classification of metagenomic reads, or identifying signature k-mers that define a specific habitat [34] [40].

Workflow for Chaos Game Representation (CGR)

The following protocol outlines the generation of a standard 2D CGR and its extension to a Frequency Matrix (FCGR), which is often used for machine learning applications [36] [37].

Title: CGR and FCGR Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define Coordinate Space: Define a 2D unit square [0,1] x [0,1]. For a 3D CGR, a cube would be used [38].

- Initialize Plot and Assign Nucleotides: Assign each nucleotide to a corner of the square (e.g., A=(0,0), C=(0,1), G=(1,1), T=(1,0)). The starting point, x₀, is typically the center of the square (0.5, 0.5) [37].

- Iterative Mapping: For each nucleotide in the sequence from first to last, calculate the next point using the iterative function: xᵢ = xᵢ₋₁ + 0.5 * (yᵢ - xᵢ₋₁) where xᵢ₋₁ is the previous point and yᵢ is the corner coordinate of the current nucleotide [37]. This formula places each new point halfway between the previous point and the current nucleotide's corner.

- Final CGR Plot: After processing the entire sequence, the resulting plot of points is the CGR, a unique fractal representation of the sequence.

- Generate FCGR Matrix (For Comparison): To compare sequences quantitatively, the CGR plot is divided into a 2k x 2k grid. The number of points falling into each cell of the grid is counted, producing a Frequency Chaos Game Representation (FCGR) matrix. This matrix is a normalized k-mer frequency table that can be used as an input for machine learning models or direct sequence comparison [36].

- Use in Comparison/ML: The FCGR matrices, which are equal-sized for all sequences, can be compared using distance metrics or used to train classifiers for ecological source tracking [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and concepts that serve as essential "reagents" in experiments involving CGR and k-mer analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Alignment-Free Analysis

| Tool/Concept | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| FCGR Matrix [36] | Computational Representation | Transforms a DNA sequence of any length into a fixed-size, numerical matrix representing k-mer frequencies, enabling machine learning. |

| Nullomers / Nullpeptides [34] | Biological Concept & Computational Target | K-mers absent from a genome or proteome. They can serve as highly specific biomarkers for pathogen detection or cancer diagnostics in ecogenomic studies. |

| IEPWRMkmer Method [39] | Computational Algorithm | An alignment-free distance measure that combines k-mer frequency and positional information via information entropy, improving phylogenetic accuracy. |

| Seqwin [40] | Software Tool | An open-source framework that uses weighted pan-genome minimizer graphs to efficiently identify signature sequences unique to a target group of microbes. |

| Digital Filter (FIR) [35] | Signal Processing Technique | A filter applied to k-mer signature signals to calculate k-mer density along a sequence, aiding in the detection of regions with distinctive word frequencies. |

| Minimizers [34] | Computational Algorithm | A heuristic to select a representative subset of k-mers from a longer sequence, significantly reducing memory consumption and computational runtime. |

Machine Learning and Neural Networks for Signature Classification

The accurate classification of signatures—whether genomic or image-based—is a cornerstone of modern scientific research, enabling everything from the diagnosis of disease to the understanding of ecological adaptations. This guide objectively compares the performance of various machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models in signature classification tasks. The context is a broader thesis on validating ecogenomic signatures across diverse habitats, a field that relies on robust classification to link genetic markers to environmental functions. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the optimal model is not merely a technical choice but a critical step in ensuring that research findings are both reliable and translatable to real-world applications. This guide provides a structured comparison of leading algorithms, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform these decisions.

Methodological Framework: A Comparative Approach

The performance evaluation of ML and DL models for signature classification follows a structured, comparative methodology. This section outlines the core experimental protocols common to the studies cited in this guide, ensuring a consistent basis for comparing the results presented in subsequent sections.

Model Selection and Training

A suite of standard and advanced models is typically evaluated. Commonly assessed machine learning models include Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), and Decision Tree (DT). For deep learning, models often include Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and specialized Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [41] [42]. Models are trained on labelled datasets where the "signature" (e.g., gene expression profile, image features) is the input and a class (e.g., diseased/healthy, bacterial/viral, signature author) is the output.

Performance Metrics

Model performance is quantified using standard metrics to ensure objectivity. Key metrics include:

- Accuracy: The proportion of total correct predictions (both positive and negative) among the total number of cases examined.

- Balanced Accuracy: Useful for imbalanced datasets, it is the average accuracy obtained from each class.

- Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC): A measure of the model's ability to distinguish between classes, where 1.0 represents perfect discrimination and 0.5 represents a random guess [43] [42].

- Sensitivity and Specificity: The true positive rate and true negative rate, respectively [43].

Validation and Testing

To prevent overfitting and ensure generalizability, models are validated on held-out test data not used during training. In some studies, an independent validation cohort is used to test the final model, providing a robust assessment of its real-world performance [43]. For genomic signatures, validation may also involve demonstrating clinical utility by comparing the signature's performance against established biomarkers like C-reactive protein (CRP) [43].

Table 1: Key Experimental Protocols in Signature Classification Studies

| Protocol Aspect | Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Selection | Identifying the most informative variables (e.g., genes, pixels) for classification. | Highly Variable Genes (HVG), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [42]. |

| Model Training | The process of feeding data to an algorithm to learn the classification function. | Training Neural Networks with cross-entropy loss [44]. |

| Cross-Validation | Assessing how the model will generalize to an independent dataset. | Held-out test sets; independent validation cohorts [43] [42]. |

| Performance Benchmarking | Comparing new models against established baselines or state-of-the-art models. | Comparing a novel three-gene signature against CRP and leukocyte count [43]. |

Comparative Performance of Classification Models

The efficacy of ML and DL models varies significantly depending on the data type and classification task. The following data, synthesized from multiple research efforts, provides a quantitative comparison.

Performance in Network Intrusion Detection

In a study on signature-based intrusion detection, which classifies network traffic as normal or intrusive, several models were evaluated. The results demonstrate that while traditional ML models perform well, DL models excel in detecting complex patterns [41].

Table 2: Model Performance in Intrusion Detection [41]

| Model | Model Type | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Machine Learning | Effective results; considered a promising solution for real-world IDS due to versatility and explainability. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Machine Learning | Effective results; promising for real-world applications due to versatility and explainability. |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Machine Learning | Showed effective results in classification. |

| Decision Tree (DT) | Machine Learning | Showed effective results in classification. |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | Deep Learning | Rapidly finds long-term and complex patterns; high precision, accuracy, and recall; suitable for nuanced, evolving threats. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Deep Learning | Rapidly finds complex patterns; highly effective with high precision, accuracy, and recall. |

Performance in Genomic Signature Classification

For biological applications, such as distinguishing between viral and bacterial infections or classifying diseased cells, the performance requirements for models are extreme due to the direct implications for diagnosis and treatment.

In one study, a minimal three-gene signature (HERC6, IGF1R, NAGK) derived from host blood transcriptomes was used to discriminate between viral and bacterial infections. The classification performance, likely powered by a logistic regression model, was exceptional. It achieved an AUROC of 0.976 (95% CI 0.919–1.000), with a sensitivity of 97.3% and specificity of 100% in one validation cohort. In a second cohort that included SARS-CoV-2 patients, it maintained an AUROC of 0.953, sensitivity of 88.6%, and specificity of 94.1%. This significantly outperformed traditional biomarkers like CRP (AUROC 0.833) [43].

In Parkinson's disease research, a Neural Network (NN) classifier applied to single-nuclei RNA sequencing data achieved a mean balanced accuracy of 0.984 in distinguishing diseased from healthy cells, outperforming logistic regression, random forest, and support vector machines. This high accuracy was crucial for downstream interpretation and gene discovery [42].

Performance in Handwritten Signature Image Classification

A novel CNN architecture (Si-CNN+NC) designed for offline handwritten signature classification demonstrated superior performance compared to several well-known pre-trained models. Its superior speed and accuracy make it suitable for applications requiring rapid processing, such as in criminal detection and forgery prevention [44].

Table 3: Model Performance in Handwritten Signature Image Classification [44]

| Model | Model Type | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Si-CNN+NC | Deep Learning (Novel CNN) | Outperformed others in both accuracy and speed; superior performance on benchmark datasets. |

| Si-CNN | Deep Learning (Novel CNN) | Achieved higher accuracy than benchmark models; fast and lightweight. |

| GoogleNet | Deep Learning (Pre-trained) | Outperformed by the proposed Si-CNN+NC model. |

| DenseNet201 | Deep Learning (Pre-trained) | Outperformed by the proposed Si-CNN+NC model. |

| Inceptionv3 | Deep Learning (Pre-trained) | Outperformed by the proposed Si-CNN+NC model. |

| ResNet50 | Deep Learning (Pre-trained) | Outperformed by the proposed Si-CNN+NC model. |

Experimental Protocols in Detail

To ensure reproducibility and provide a deeper understanding of the comparative data, this section elaborates on the experimental protocols for two key studies.

Protocol 1: Validating a Three-Gene Viral Infection Signature

This study aimed to derive and validate a blood transcriptional signature for detecting viral infections, including COVID-19, in emergency department settings [43].

- Sample Collection: Whole-blood RNA was prospectively collected from adults (≥18 years) presenting with suspected infection to a major UK hospital. Participants were recruited into discovery and validation cohorts.

- Discovery Cohort: RNA sequencing was performed on samples from 56 participants with confirmed bacterial infections and 27 with viral infections. Differential gene expression analysis identified host genes that were significantly over- or under-expressed.

- Signature Derivation: A feature selection method (Forward Selection-Partial Least Squares, FS-PLS) was used to identify the most parsimonious set of discriminating genes, resulting in a three-gene signature (HERC6, IGF1R, NAGK). A logistic regression model was developed using this signature.

- Validation: The signature was translated into an RT-qPCR assay and validated on two independent prospective cohorts: one with undifferentiated fever and another with PCR-confirmed COVID-19 or bacterial infection. Performance was assessed by calculating AUROC, sensitivity, and specificity.

Protocol 2: Neural Networks for Parkinson's Disease Gene Signatures

This research introduced an explainable ML framework to identify molecular markers of Parkinson's disease (PD) from single-nuclei transcriptomes [42].

- Data Preparation: Four publicly available snRNAseq datasets from post-mortem midbrains of PD patients and controls were used. Cells were annotated into broad types (e.g., astrocytes, microglia, dopaminergic neurons).

- Feature Selection and Model Training: Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) were identified for each cell type. Neural Network (NN) classifiers were then trained using these HVGs to predict disease status at the single-cell level.

- Model Interpretation: The Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) method was applied to the trained NNs. LIME approximates the local decision boundary for each prediction, assigning an importance score (Z-score) to each gene, thereby revealing the transcriptional markers that most strongly influenced the classification of a cell as "diseased."

- Validation: The generalizability of the LIME-identified gene signatures was tested by comparing their importance across different datasets and against genes identified by traditional differential expression analysis.