Unlocking Microbial Dark Matter: A Guide to High-Throughput Sequencing in Modern Ecology

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) has revolutionized microbial ecology, moving research beyond mere cataloging to functional and mechanistic insights.

Unlocking Microbial Dark Matter: A Guide to High-Throughput Sequencing in Modern Ecology

Abstract

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) has revolutionized microbial ecology, moving research beyond mere cataloging to functional and mechanistic insights. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of HTS technologies—from short-read Illumina to long-read PacBio and Oxford Nanopore platforms—and their applications in profiling complex microbiomes. It covers foundational concepts, methodological workflows, troubleshooting for optimization, and comparative validation of platforms, with a focus on leveraging these tools for biomedical discovery, therapeutic development, and understanding host-microbe interactions in health and disease.

The HTS Revolution: From Sanger Sequencing to Unraveling Complex Microbial Ecosystems

High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS), often referred to as Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), represents a revolutionary technological advancement that has transformed genomics research by enabling the parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [1] [2] [3]. This massive parallelization stands in stark contrast to traditional Sanger sequencing, which was limited by its minimal throughput and substantial cost [2] [4]. The core principle underlying all HTS technologies involves the fragmentation of DNA or RNA molecules into smaller pieces, followed by the attachment of adapters, parallel sequencing of these fragments, and subsequent computational reassembly of the sequences [2]. This fundamental approach has drastically reduced the time and cost associated with genomic studies while providing unprecedented scalability, making it possible to sequence entire genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes with remarkable speed and precision [2] [3].

The evolution of sequencing technologies has progressed through distinct generations, beginning with first-generation Sanger sequencing that enabled the landmark Human Genome Project but required 13 years and approximately $3 billion to complete [1]. The limitations of this method catalyzed the development of second-generation sequencing platforms (including Illumina and Ion Torrent) that dominated the HTS market for years, though they still relied on clonal amplification which could introduce bias and generated relatively short reads [1]. Most recently, third-generation sequencing technologies such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) have emerged, offering the ability to sequence single molecules without amplification and producing significantly longer reads [1] [3]. This technological progression has profoundly impacted microbial ecology research, allowing scientists to explore the vast complexity of microbial communities in environmental samples with unprecedented resolution [5] [6].

Key HTS Technology Platforms and Principles

Comparative Analysis of Major HTS Platforms

Table 1: Comparison of Major High-Throughput Sequencing Technologies

| Technology | Sequencing Principle | Read Length | Accuracy | Throughput | Key Applications in Microbial Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye terminators [1] [3] | Short to medium (150-300 bp) [1] | High [1] [2] | High [1] | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, metagenomics, transcriptomics [7] [3] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing detecting H+ ions [1] [3] | Short to medium (~200 bp) [1] | Moderate to high [1] [2] | Moderate to high [2] | Targeted amplicon sequencing, microbial genomics [2] [3] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single Molecule, Real-Time sequencing [1] [3] | Long (>10 kb) [1] | High (error rates <1%) [1] | Moderate [1] | De novo genome assembly, full-length 16S sequencing, epigenetic modification detection [1] [3] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore-based electrical signal detection [1] [3] | Long (>10 kb up to 4 Mb) [1] | Variable [1] [2] | Moderate to high [2] | Real-time pathogen surveillance, metagenome-assembled genomes, in-field sequencing [5] [2] |

Detailed Technological Principles

Illumina Sequencing employs a sequencing-by-synthesis approach with reversible dye terminators [3]. The process begins with DNA fragmentation and adapter ligation, followed by bridge amplification on a glass slide that creates clusters of identical DNA fragments [1]. During sequencing cycles, fluorescently labeled nucleotides are incorporated, imaged, and then cleaved to allow the next incorporation cycle [1]. This method generates high-quality short-read data ideal for quantitative applications like transcriptomics and targeted sequencing [2].

Oxford Nanopore Technology operates on a fundamentally different principle by measuring changes in electrical current as DNA or RNA molecules pass through protein nanopores embedded in a membrane [1] [2]. The technology does not require amplification or fragmentation, enabling direct sequencing of native nucleic acids and providing ultra-long reads that are particularly valuable for assembling complete genomes from complex microbial communities [5] [2]. The portability of MiniON devices allows for real-time, in-field sequencing applications [2].

PacBio SMRT Sequencing utilizes zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) - nanoscale wells that contain a single DNA polymerase molecule immobilized at the bottom [1]. As the polymerase incorporates fluorescently labeled nucleotides, the incorporation event is detected in real-time [1] [3]. This approach generates long reads with high accuracy, making it particularly suitable for resolving complex genomic regions and detecting epigenetic modifications in microbial genomes [1].

HTS Applications in Microbial Ecology

High-Throughput Sequencing has revolutionized microbial ecology by providing powerful tools to explore the immense diversity of microbial communities in environmental samples without the need for cultivation [5]. Metagenomics, enabled by HTS, allows researchers to recover metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) directly from environmental samples, dramatically expanding our knowledge of microbial diversity [5]. Recent studies utilizing long-read Nanopore sequencing of 154 complex soil and sediment samples successfully recovered 15,314 previously undescribed microbial species, expanding the phylogenetic diversity of the prokaryotic tree of life by 8% [5]. This demonstrates the remarkable power of HTS to uncover the vast, unexplored microbial dark matter.

Amplicon-based HTS approaches, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing, have become standard for profiling microbial communities across diverse environments [7] [6]. These methods provide insights into microbial community structure, diversity, and dynamics in response to environmental changes and perturbations. For instance, HTS metabarcoding has been effectively employed to monitor the impact of agricultural practices on soil fungal communities, revealing how soil fumigation and biostimulant application alter microbial interactions and ecosystem functioning [7]. The technology has proven essential for understanding host-microbe interactions, biogeochemical cycling, and the ecological principles governing microbial community assembly and stability [6] [8].

Advanced applications in microbial ecology increasingly leverage the complementary strengths of multiple sequencing platforms. For example, the combination of short-read Illumina data for high accuracy and long-read Nanopore or PacBio data for improved genome assembly has enabled the recovery of high-quality microbial genomes from highly complex environments like soil [5]. Furthermore, the development of absolute quantification sequencing methods addresses the limitations of relative abundance data, providing more accurate characterization of microbial population dynamics and interactions [6].

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Ecology

Metagenome-Assembled Genome Recovery from Complex Soil Samples

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HTS in Microbial Ecology

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality nucleic acid extraction from complex matrices | Soil, sediment, or water sample processing [5] |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of target genes for amplicon sequencing | 16S rRNA gene amplification for community profiling [7] |

| Sequence Adapters | Platform-specific ligation for library preparation | Illumina, Nanopore, or PacBio library construction [2] |

| Size Selection Beads | Fragment size selection for optimized sequencing | Magnetic bead-based clean-up and size selection [5] |

| Quality Control Kits | Assessment of DNA quality and quantity | Fluorometric quantification and fragment analysis [5] |

| Spike-in Standards | Absolute quantification of microbial abundances | Known quantity external standards for normalization [6] |

The recovery of high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes from complex terrestrial habitats represents a grand challenge in metagenomics due to the enormous microbial diversity and complexity of these environments [5]. The following protocol outlines a robust workflow for MAG recovery using long-read sequencing:

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect soil or sediment samples using sterile corers and store immediately at -80°C to preserve nucleic acid integrity.

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA using a protocol optimized for complex environmental samples, such as the CTAB-based method with subsequent purification.

- Assess DNA quality and quantity using fluorometry and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to confirm high molecular weight.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing libraries without fragmentation to maintain long DNA molecules.

- For Nanopore sequencing: Use the ligation sequencing kit, paying particular attention to DNA repair and end-prep steps to maximize library complexity.

- Sequence with a PromethION flow cell, aiming for approximately 100 Gbp of data per sample to ensure sufficient coverage for genome reconstruction [5].

Bioinformatic Processing with mmlong2 Workflow:

- Perform metagenome assembly using Flye or similar long-read assemblers optimized for complex metagenomic data.

- Conduct iterative binning using multiple binners (e.g., MetaBAT2, MaxBin2) with differential coverage information from multiple samples.

- Apply the mmlong2 workflow, which includes ensemble binning and iterative refinement steps to improve MAG recovery from highly complex datasets [5].

- Assess MAG quality using CheckM or similar tools, retaining only medium and high-quality genomes based on completeness and contamination metrics.

Absolute Quantification Sequencing for Microbial Community Analysis

Traditional HTS approaches generate relative abundance data that can mask important population dynamics in microbial communities [6]. Absolute quantification sequencing addresses this limitation through the use of internal standards:

Spike-in Standard Preparation:

- Select or create DNA standards representing sequences not found in your sample type.

- Precisely quantify the standard using digital PCR or similar absolute quantification method.

- Add a known amount of spike-in standard to each sample prior to DNA extraction.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Proceed with standard library preparation protocols appropriate for your sequencing platform.

- Include negative controls to assess background contamination.

- Sequence with sufficient depth to detect both rare community members and spike-in standards.

Data Analysis and Absolute Abundance Calculation:

- Process sequencing data through standard bioinformatic pipelines for amplicon or metagenomic analysis.

- Calculate absolute abundances using the formula: Absolute abundance = (Sample read count / Spike-in read count) × Known spike-in molecules.

- Analyze co-occurrence patterns and community assembly processes using absolute rather than relative abundances to avoid compositional data artifacts [6].

Technological Evolution and Future Perspectives

The evolution of HTS technologies has progressed remarkably from the first automated Sanger sequencers to the current landscape of diverse platforms each with unique strengths [4] [3]. Second-generation technologies dominated the market for over a decade, but recent advances in third-generation long-read sequencing are increasingly addressing their limitations regarding read length and amplification bias [1]. The continuing evolution of HTS is characterized by several key trends: the convergence of long-read and short-read technologies to leverage their complementary advantages, the development of more sophisticated bioinformatic tools to handle increasingly complex datasets, and the emergence of novel applications that push the boundaries of what can be achieved with sequencing technologies [5] [3].

Future developments in HTS will likely focus on enhancing the accuracy and sensitivity of sequencing data, reducing costs further, improving the accessibility of the technology, and developing more efficient and scalable computational solutions for data analysis [3]. For microbial ecology specifically, the integration of absolute quantification methods, multi-omics approaches, and synthetic microbial ecosystem studies will provide unprecedented insights into the principles governing microbial community assembly, stability, and function [6] [8]. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly uncover new dimensions of microbial diversity and function, further expanding our understanding of the microbial world and its critical roles in ecosystem health and functioning.

The landscape of high-throughput sequencing for microbial ecology is dominated by three major platforms: Illumina, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT). Each employs a distinct sequencing biochemistry, leading to complementary strengths in output, resolution, and application.

Illumina technology utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye-terminators. This approach generates massive volumes of short reads (typically 300-600 bp for MiSeq/NovaSeq systems) with very high per-base accuracy (Q30, >99.9%). For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, it typically targets specific hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4, ~450 bp) [9] [10]. This high accuracy makes it a benchmark for quantitative abundance measurements.

PacBio employs Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing. DNA polymerase incorporates fluorescently tagged nucleotides into a template immobilized at the bottom of a zero-mode waveguide. Its key innovation is Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS), where a single DNA molecule is sequenced repeatedly in a loop. This produces long, accurate reads known as HiFi reads, which combine long read lengths (10-25 kb) with high accuracy (Q27, ~99.9%) [9] [11]. This is ideal for sequencing the full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp).

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) is based on the passage of single DNA or RNA strands through protein nanopores embedded in an electrical-resistant membrane. Each nucleotide base causes a characteristic disruption in the ionic current as it passes through the pore, enabling real-time, long-read sequencing. Early versions had higher error rates, but recent chemistries (R10.4.1 flow cells) and basecalling algorithms have significantly improved accuracy to over 99% [9] [12] [10]. ONT can sequence full-length 16S rRNA amplicons and is notable for its portability and real-time data stream.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Sequencing Platforms for 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

| Feature | Illumina | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Chemistry | Sequencing-by-synthesis | SMRT (Single Molecule, Real-Time) | Nanopore-based electronic sensing |

| Typical 16S Read Length | Short (300-600 bp, e.g., V3-V4) | Long (Full-length, ~1,450 bp) | Long (Full-length, ~1,400-1,500 bp) |

| Key Read Type | Short reads | HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads | Continuous long reads |

| Per-base Accuracy | Very High (~Q30, >99.9%) | Very High (~Q27, ~99.9%) | Moderate-High (Recent: >Q20, >99%) [9] [12] |

| Primary 16S Application | Amplicon (hypervariable regions) | Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing | Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing |

| Typical Output per Run | High (Millions of reads) | Moderate | Variable (Scalable from MinION to PromethION) |

| Run Time | 1-3 days | 0.5-2 days | 1-72 hours (real-time) [10] |

| Species-Level Resolution | Lower (e.g., 48% in rabbit gut) [9] | Higher (e.g., 63% in rabbit gut) [9] | Highest (e.g., 76% in rabbit gut) [9] |

Performance in Microbial Ecology Studies

Comparative studies reveal how these platform characteristics translate into performance for profiling complex microbial communities, such as those found in the gut, soil, and respiratory tract.

Taxonomic Resolution

A key advantage of long-read sequencing is improved taxonomic resolution. A 2025 study on rabbit gut microbiota directly compared the three platforms, demonstrating a clear hierarchy in species-level classification rates: ONT (76%), followed by PacBio (63%), and then Illumina (48%) [9]. Full-length 16S rRNA sequences allow for analysis across all nine hypervariable regions, providing more phylogenetic information for discriminating between closely related species than single or paired hypervariable regions [12] [10].

However, a significant challenge across all platforms is the high proportion of sequences assigned to "uncultured_bacterium" at the species level, highlighting limitations in current reference databases rather than the technologies themselves [9].

Diversity Metrics and Community Composition

The choice of platform can influence the observed microbial community structure:

- Alpha Diversity (Richness/Evenness): Illumina often captures greater species richness, likely due to its higher sequencing depth and accuracy, which can better detect rare taxa. Community evenness, however, is often comparable between platforms [10].

- Beta Diversity (Between-Sample Differences): Studies show that while overall community patterns are consistent, the specific platform and primer choice can create a significant "batch effect" in beta diversity analyses. For instance, a rabbit gut study found significant differences in taxonomic composition between Illumina, PacBio, and ONT, even after using standardized bioinformatics [9]. This effect can be more pronounced in complex microbiomes like soil or gut compared to lower-biomass environments like the respiratory tract [10].

- Taxonomic Abundance Biases: Platform-specific biases in taxonomic abundance are well-documented. For example, a respiratory microbiome study using the ANCOM-BC2 tool found that ONT overrepresented certain taxa like Enterococcus and Klebsiella while underrepresenting others like Prevotella and Bacteroides compared to Illumina [10]. These biases may stem from differences in DNA extraction, PCR amplification, or the sequencing chemistry itself.

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Microbial Community Analysis

| Performance Metric | Illumina | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species-Level Classification Rate | Lower (e.g., 48%) [9] | Medium (e.g., 63%) [9] | Higher (e.g., 76%) [9] |

| Detection of Rare Taxa | Excellent (High depth) | Good | Good, but can be influenced by error rate |

| Quantitative Accuracy (Abundance) | High (Gold standard) | High | Good, with modern error-correction |

| Bias in Taxonomic Profile | Under-represents GC-rich regions [13] | More uniform genome coverage | Can over/under-represent specific taxa [10] |

| Community Differentiation | Clear clustering by sample type [12] | Clear clustering by sample type [12] | Clear clustering by sample type, but may show platform-specific separation [9] [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Below are standardized protocols for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing on each platform, as applied in recent microbial ecology studies.

Illumina 16S rRNA (V3-V4) Amplicon Sequencing Protocol

This protocol is adapted from the Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation guide and used in recent comparative studies [9] [10].

- Step 1: PCR Amplification. Amplify the target hypervariable region (e.g., V3-V4) from genomic DNA using region-specific primers (e.g., S-D-Bact-0341-b-S-17 / S-D-Bact-0785-a-A-21) [9]. A typical reaction uses 2X KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix and the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 25 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

- Step 2: Library Indexing and Amplification. A second, limited-cycle PCR reaction (8 cycles) is performed to attach dual indices and sequencing adapters using the Nextera XT Index Kit.

- Step 3: Library Pooling and Clean-up. The indexed PCR products are purified using magnetic beads (e.g., AMPure XP), quantified, and normalized. Libraries are then pooled in equimolar amounts.

- Step 4: Sequencing. The pooled library is denatured, diluted, and loaded onto an Illumina flow cell (e.g., MiSeq Reagent Kit v3) for paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2 × 300 cycles).

PacBio Full-Length 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Protocol

This protocol leverages PacBio's HiFi read capability for highly accurate full-length 16S sequences [9] [12].

- Step 1: Full-Length 16S Amplification. Amplify the full-length 16S rRNA gene (~1,500 bp) from genomic DNA using universal primers (e.g., 27F and 1492R), which are tailed with PacBio barcode sequences for multiplexing. A typical reaction uses KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA Polymerase and the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 min; 27-30 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 57°C for 30 s, 72°C for 60 s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [9].

- Step 2: Library Preparation. The amplified and barcoded DNA is pooled in equimolar concentrations. A SMRTbell library is constructed using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 or 3.0, which involves DNA repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation to create the circularizable template [9] [12].

- Step 3: Sequencing on Sequel II/IIe System. The prepared library is bound to polymerase, loaded onto a SMRT Cell, and sequenced on a Sequel II or IIe system using a Sequel II Binding Kit and Sequencing Kit. The run is configured for CCS mode to generate HiFi reads.

Oxford Nanopore Full-Length 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Protocol

This protocol is based on the ONT Microbial Amplicon Barcoding Kit (SQK-MAB114.24), which offers a rapid and flexible workflow [14] [15].

- Step 1: Full-Length 16S or ITS Amplification. Amplify the target gene using the provided 16S or ITS primers (e.g., 27F and 1492R) and a high-fidelity master mix (e.g., LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix). Cycling conditions: 95°C for 1 min; 35-40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 58°C for 30 s, 65°C for 2 min; final extension at 65°C for 5 min [14].

- Step 2: Amplicon Barcoding (Rapid Adapter Ligation). The PCR amplicons are directly barcoded using the kit's Amplicon Barcodes 01-24 in a rapid, 15-minute reaction that simultaneously inactivates the barcodes [14].

- Step 3: Sample Pooling and Clean-up. The barcoded samples are pooled and purified using AMPure XP beads to remove short fragments and reagents [14].

- Step 4: Adapter Ligation and Loading. The Rapid Adapter is ligated to the purified, barcoded amplicons in a 5-minute reaction. The library is then immediately primed and loaded onto a MinION flow cell (R10.4.1 recommended) for sequencing [14] [10].

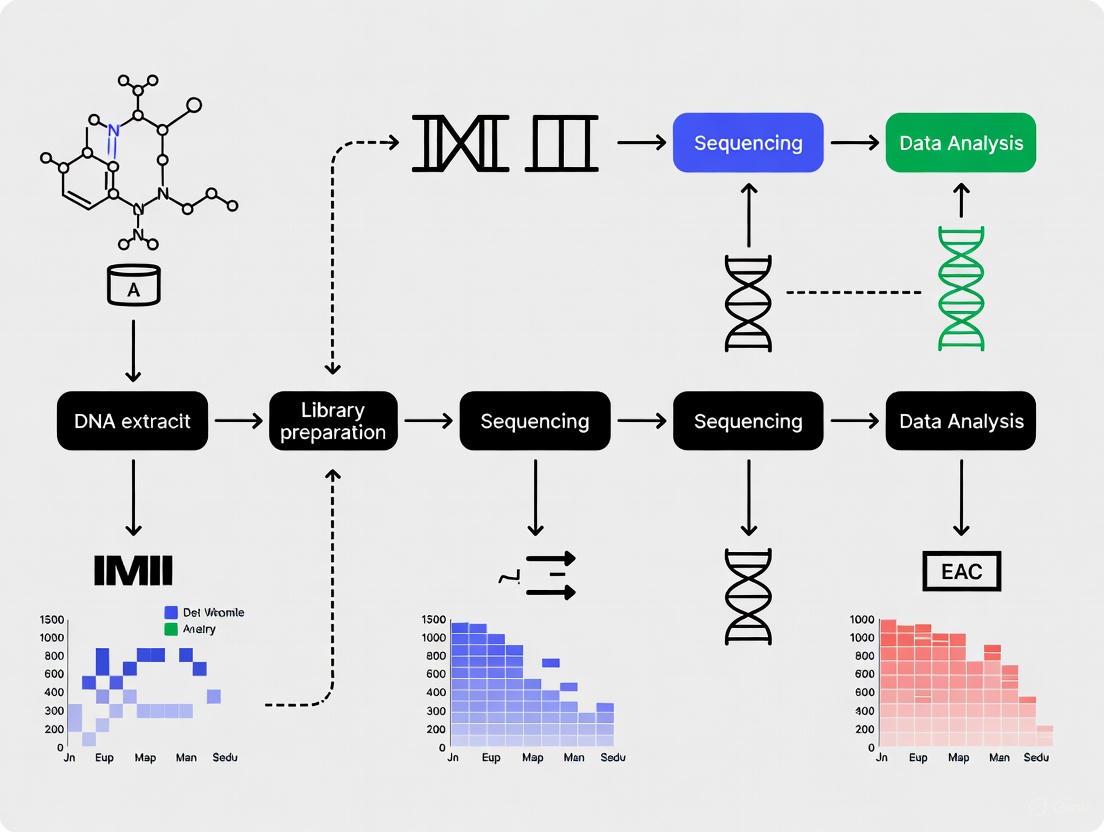

Diagram 1: 16S rRNA Sequencing Workflow Comparison. The workflow diverges during library preparation, where platform-specific primers and chemistries are applied, then reconverges for downstream bioinformatic analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| gDNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality, inhibitor-free genomic DNA from complex samples (feces, soil, sputum). | Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Microprep Kit (Zymo Research) [12], DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) [9] |

| PCR Enzyme Master Mix | Amplifies the target 16S rRNA region with high fidelity and yield. | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche), LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix (NEB) [14] |

| Library Prep Kit (Illumina) | Prepares amplicons for sequencing on Illumina systems, including indexing. | 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Prep Protocol [9], QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel (Qiagen) [10] |

| Library Prep Kit (PacBio) | Creates SMRTbell libraries from amplicons for HiFi sequencing. | SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0/3.0 (PacBio) [9] [12] |

| Library Prep Kit (ONT) | Rapid barcoding and adapter ligation for nanopore sequencing. | Microbial Amplicon Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-MAB114.24) (ONT) [14] [15] |

| Magnetic Beads | Size selection and clean-up of PCR products and final libraries. | AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) [9] [14] |

| Flow Cell | The consumable where sequencing occurs. | MiSeq Reagent Kit (Illumina), SMRT Cell (PacBio), MinION Flow Cell (R10.4.1) (ONT) [14] [10] |

| Quality Control Tools | Quantifies and qualifies DNA and libraries pre-sequencing. | Qubit Fluorometer & dsDNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher) [9], Fragment Analyzer (Agilent) [9] |

Application Notes and Implementation Guidance

Platform Selection Guide

Choosing the optimal platform depends on the specific research objectives, budget, and infrastructure [10]:

- Choose Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq when: The primary goal is high-throughput, cost-effective profiling of microbial communities at the genus level. It is ideal for large-scale cohort studies where high accuracy and depth are critical for detecting rare taxa and quantifying abundances [9] [10].

- Choose PacBio Revio/Sequel IIe when: The research demands high-resolution, species-level taxonomy from amplicons and requires the highest possible accuracy for long reads. It is the preferred choice for generating publication-quality, full-length 16S data where budget is less constrained [9] [11] [12].

- Choose ONT MinION/PromethION when: The application requires species-level resolution, real-time data stream, portability for in-field sequencing, or the flexibility to run a few to many samples on demand. Its rapid workflow enables same-day results [15] [10].

Critical Considerations for Experimental Design

- Database Limitations: A significant bottleneck is not the technology but reference databases. A high proportion of species-level assignments may be labeled "uncultured_bacterium," limiting biological insights [9]. Curated, environment-specific databases can improve annotation.

- Primer and Platform Effects: The combination of primer choice and sequencing platform can introduce significant biases in perceived community composition. It is strongly discouraged to directly compare or merge datasets generated with different platforms or primer sets without appropriate batch-effect correction [9].

- Bioinformatic Pipelines: The optimal data processing pipeline differs by platform. Illumina and PacBio HiFi data are typically processed with DADA2 for Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), while ONT data may require specialized tools like the EPI2ME 16S workflow, Emu, or Spaghetti to handle its unique error profile [9] [10].

Within the framework of high-throughput sequencing for microbial ecology research, selecting the appropriate method for microbiome analysis is a critical first step that fundamentally shapes the scope and validity of a study's findings. The two predominant methodologies—amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics—offer distinct lenses through which to examine microbial communities [16]. Amplicon sequencing, which involves the targeted amplification and sequencing of conserved marker genes like the 16S rRNA gene for bacteria and archaea, has been a cornerstone of microbial ecology for decades, providing a cost-effective means of assessing taxonomic composition [17] [18]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics employs an untargeted approach, randomly sequencing all DNA fragments within a sample to simultaneously reveal taxonomic identity and functional potential [19] [20]. The choice between these techniques is not a matter of superiority but of alignment with the specific research question, considering factors such as required taxonomic resolution, the need for functional insight, sample type, and available resources [16] [21]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these platforms and details standardized protocols to guide researchers in making an informed selection and generating high-quality data for their investigations in microbial ecology and drug development.

Comparative Analysis: Amplicon Sequencing vs. Shotgun Metagenomics

A direct comparison of the technical and practical aspects of amplicon and shotgun sequencing reveals a clear trade-off between resource expenditure and informational yield. The decision matrix must balance the research objectives against practical constraints.

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison between Amplicon and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Feature | Amplicon Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Targeted amplification of specific marker genes (e.g., 16S, 18S, ITS) [17] | Untargeted, random sequencing of all DNA in a sample [20] |

| Typical Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level; sometimes species-level, highly dependent on region targeted [21] [22] | Species-level and often strain-level; enables detection of single nucleotide variants [21] |

| Functional Profiling | Not available directly; possible only via prediction algorithms (e.g., PICRUSt) [21] | Yes, provides direct insight into functional gene content and metabolic pathways [19] [20] |

| Organisms Detected | Primarily bacteria & archaea (16S); fungi (ITS); microbial eukaryotes (18S) [17] | All domains: bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses [20] [21] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower; cost-effective for large-scale studies [17] [18] | Higher; typically 2-3x the cost of amplicon sequencing [21] |

| Bioinformatic Complexity | Moderate; well-established, standardized pipelines (e.g., QIIME 2, DADA2) [20] [22] | High; requires sophisticated resources and tools for assembly, binning, and annotation [20] [22] |

| Host DNA Contamination | Low risk due to targeted amplification [21] | High risk; can dominate sequencing data, requiring depletion strategies or deep sequencing [21] |

| Primary Applications | Phylogenetic studies, biodiversity assessments, microbial composition analysis across large sample cohorts [17] [18] | Functional potential analysis, pathogen discovery, strain-level tracking, genome reconstruction (MAGs) [19] [20] |

Table 2: Quantitative and Performance Metrics Based on Empirical Data

| Metric | Amplicon Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity in Low-Biomass Samples | High; due to PCR amplification of target [18] | Lower; unless subjected to deep sequencing, which increases cost [20] |

| Correlation with Biomass | Variable; can be skewed by primer mismatches and gene copy number variation [16] | Stronger; generally provides a better correlation between read abundance and biomass [16] |

| Data Sparsity | Higher; detects only a fraction of the community revealed by shotgun [22] | Lower; captures a broader and more even community profile [22] |

| Alpha Diversity | Lower reported values compared to shotgun [22] | Higher reported values; captures greater microbial richness [22] |

| Database Dependency | Relies on 16S/ITS databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) [22] | Relies on whole-genome databases (e.g., NCBI RefSeq, GTDB) [22] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing for Bacterial Profiling

This protocol outlines a standardized method for characterizing bacterial communities via amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions, optimized for the Illumina MiSeq platform.

3.1.1 Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Preserve samples immediately after collection. For stool, skin, or environmental samples, use sterile, DNA-free containers and flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen or store at -80°C. For stabilization without freezing, use nucleic acid preservation buffers like RNAlater [19].

- DNA Extraction: Extract high-molecular-weight DNA using kits designed for complex samples (e.g., DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) or NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel)) [22]. Include negative extraction controls to monitor reagent contamination. Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) to ensure accurate normalization.

3.1.2 Library Preparation and Sequencing

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the hypervariable V3-V4 region using primers 341F (5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') and 805R (5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3') [22].

- Reaction Mix: 2x KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix, 10 μM each primer, and 10-50 ng template DNA.

- Cycling Conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 25-30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [22].

- Amplicon Clean-up: Purify PCR products using magnetic beads (e.g., AMPure XP) to remove primers and dimers.

- Indexing PCR & Pooling: Add dual indices and Illumina sequencing adapters in a second, limited-cycle PCR. Quantify amplicons, normalize equimolarly, and pool into a single library.

- Sequencing: Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq with v3 chemistry, targeting 50,000 paired-end reads per sample to achieve saturation in diversity curves [18].

3.1.3 Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

- Demultiplexing: Assign raw sequencing reads to samples based on their unique barcodes.

- Quality Filtering & Trimming: Use DADA2 (v1.22+) to filter reads based on quality profiles, trim primers, and truncate reads (e.g., 290 bp forward, 230 bp reverse) [22].

- Inference of ASVs: Apply the DADA2 algorithm to learn error rates and infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), providing single-nucleotide resolution.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify ASVs against the SILVA (v138) or Greengenes2 reference database. For enhanced species-level classification, a complementary k-mer-based classification with Kraken2/Bracken2 against the NCBI RefSeq database is recommended [22].

- Data Export: Generate a feature table (ASVs), a taxonomy table, and a phylogenetic tree for downstream ecological analysis.

Protocol 2: Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing for Comprehensive Community Analysis

This protocol details a workflow for shotgun metagenomics, enabling simultaneous taxonomic profiling at high resolution and functional characterization of microbial communities.

3.2.1 Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- High-Quality DNA Extraction: The foundation of a successful shotgun library is high-molecular-weight, high-purity DNA. Use kits validated for metagenomics (e.g., NucleoSpin Soil Kit) [22]. For samples with high host DNA contamination (e.g., tissue, blood), implement host DNA depletion kits (e.g., NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit) to increase microbial sequence yield [21].

- DNA QC: Assess DNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer and quantify via fluorometry.

3.2.2 Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Construction: Fragment 100-500 ng of input DNA via acoustic shearing (Covaris) to a target size of 350-550 bp. Use a commercial library prep kit (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) for end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation [20]. Perform limited-cycle PCR to index libraries.

- Library QC and Pooling: Quantify final libraries by qPCR and confirm size distribution using a Bioanalyzer. Pool libraries equimolarly.

- Sequencing: Sequence on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 to a depth of 20-50 million paired-end (2x150 bp) reads per sample for complex communities like gut microbiota or soil [21] [22]. Deeper sequencing (e.g., 100+ million reads) may be required for metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) reconstruction.

3.2.3 Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

- Pre-processing: Remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic or fastp.

- Host Read Removal: Align reads to the host genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human-associated samples) using Bowtie2 and discard matching reads [22].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Directly classify reads against a curated genome database (e.g., Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome (UHGG) database or GTDB) using tools like Kraken2 and quantify abundances with Bracken [22].

- Functional Profiling: Align reads to a functional database (e.g., KEGG, eggNOG) using HUMAnN3 to determine pathway abundances [21].

- De Novo Assembly and Binning: For MAG recovery, assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs using metaSPAdes. Bin contigs into draft genomes using metaBAT2. Check MAG quality (completeness, contamination) with CheckM [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Workflows

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products/Kits |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA from complex samples. | NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel), DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) [22] |

| Host DNA Depletion Kit | Selective removal of host genomic DNA from samples with high host:microbe ratio. | NEBNext Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit [21] |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplification of specific hypervariable regions for amplicon sequencing. | 341F/805R for V3-V4 region [22] |

| Library Preparation Kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from fragmented DNA. | Illumina DNA Prep Kit [20] |

| DNA Quantitation Kits | Accurate quantification of DNA and final library concentrations. | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit |

| Bioinformatics Tools | For data processing, analysis, and interpretation. | QIIME 2, DADA2 (Amplicon) [22]; Kraken2, HUMAnN3, metaSPAdes, metaBAT2 (Shotgun) [19] [22] |

| Reference Databases | For taxonomic classification and functional annotation. | SILVA, Greengenes (16S) [22]; UHGG, GTDB, KEGG (Shotgun) [22] |

The strategic choice between amplicon and shotgun metagenomics is pivotal for the success of any microbial ecology research project. Amplicon sequencing remains a powerful, cost-efficient tool for large-scale studies focused on compositional differences and broad taxonomic profiling, particularly in well-defined systems or when sample biomass is low [18] [21]. Conversely, shotgun metagenomics is the unequivocal choice for studies demanding high taxonomic resolution, comprehensive functional insight, or genome-level reconstruction, despite its higher computational and financial costs [19] [20]. As the field advances, the integration of both methods—using amplicon sequencing for broad screening and shotgun on a subset for in-depth analysis—or the harmonization of datasets from both platforms presents a powerful approach to leverage their respective strengths [23]. By aligning the methodological choice with the core research question and adhering to the robust protocols outlined herein, researchers can effectively harness the power of high-throughput sequencing to unravel the complexities of microbial ecosystems.

The field of microbial ecology has been revolutionized by culture-independent methods that allow the identification and characterization of microorganisms from all domains of life directly from their environment [24]. Two primary methodological approaches have emerged as cornerstones of modern microbiome research: marker gene sequencing (primarily targeting the 16S rRNA gene) and whole-genome shotgun (WGS) metagenomics [24]. The development of these approaches, coupled with advanced high-throughput sequencing technologies, has enabled researchers to move beyond cataloging microbial membership to understanding functional capabilities and ecological dynamics within complex microbial communities [24].

Marker gene studies provide a targeted analysis of specific taxonomic groups by sequencing conserved genetic regions, while WGS metagenomics sequences the total DNA content of a sample, enabling comprehensive profiling of biodiversity and functional potential [24]. The choice between these techniques depends on the research questions, with each offering distinct advantages and limitations that must be considered in experimental design. These technological advances have opened new frontiers in understanding microbial communities' roles in human health, environmental processes, and biotechnological applications.

Methodological Foundations

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The 16S ribosomal RNA gene is a cornerstone of microbial ecology, serving as a phylogenetic marker for identifying and classifying bacteria and archaea. This approach leverages conserved regions for primer binding and variable regions for taxonomic differentiation [25].

Key Workflow Steps:

- DNA Extraction and Target Amplification: Microbial DNA is extracted from samples, and the 16S rRNA gene (or specific variable regions like V3-V4) is amplified using universal primers.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplified products are prepared into sequencing libraries compatible with platforms such as Illumina MiSeq.

- Bioinformatic Processing: Raw sequences are quality-filtered, denoised into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), and classified against reference databases.

Table: Common 16S rRNA Hypervariable Regions and Their Applications

| Region | Length (bp) | Taxonomic Resolution | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V3 | ~500 | Genus to species | Broad-range bacterial diversity |

| V3-V4 | ~450 | Genus-level [25] | Human gut microbiome studies [25] |

| V4 | ~250 | Genus-level | Environmental samples, high-throughput studies |

| Full-length 16S | ~1500 | Species-level [25] | High-resolution taxonomic profiling |

Advanced Protocol: Species-Level Identification with V3-V4 Regions

Traditional analysis of the V3-V4 regions is often limited to genus-level classification. However, a novel pipeline achieves species-level identification by addressing the limitation of fixed similarity thresholds [25].

Experimental Protocol:

Database Construction:

- Integrate seed sequences from authoritative databases (SILVA, NCBI RefSeq, LPSN) [25].

- Supplement with 16S rRNA sequences from 1,082 human gut samples to improve coverage, particularly for anaerobes and uncultured organisms [25].

- Create a non-redundant ASV database specific to the V3-V4 regions (positions 341–806) [25].

Threshold Determination:

Taxonomic Classification with ASVtax Pipeline:

This methodology significantly enhances species-level classification from V3-V4 data, facilitating more reliable ecological and functional interpretations [25].

Whole-Genome Shotgun Metagenomics

WGS metagenomics sequences the total DNA from a sample without targeting specific genes, enabling functional profiling and the reconstruction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [24].

Key Workflow Steps:

- DNA Extraction and Library Preparation: Extract total genomic DNA, with optional host DNA depletion for low-biomass samples. Prepare sequencing libraries without PCR amplification where possible.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence using Illumina (short-read) or PacBio/Oxford Nanopore (long-read) platforms.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Quality control, assembly, binning into MAGs, and taxonomic/functional annotation.

Table: Comparison of Sequencing Technologies for Metagenomics

| Technology | Read Length | Throughput | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 150-300 bp | Up to 6 Tb (NovaSeq) [24] | High accuracy, low cost per base | Short reads complicate assembly |

| PacBio HiFi | 10-25 kb | 1-6 Tb (DNBSEQ-T7) [24] | Long, accurate reads ideal for MAGs [26] | Higher cost, more DNA required |

| Oxford Nanopore | Up to hundreds of kb | ~10 Gb per run (MinION) [24] | Ultra-long reads, real-time analysis | Higher error rate (~2.5%) [24] |

Advanced Protocol: Genome-Resolved Metagenomics with Long Reads

Long-read sequencing technologies are overcoming the "grand challenge" of recovering high-quality genomes from highly complex environments like soil [5]. The following protocol is adapted from the mmlong2 workflow used to recover over 15,000 previously undescribed microbial species from terrestrial habitats [5].

Experimental Protocol:

Deep Long-Read Sequencing:

Metagenome Assembly and Processing:

- Assemble reads into contigs using long-read assemblers (e.g., Canu, Flye).

- Polish assemblies with original read data to improve accuracy.

- Remove eukaryotic contigs based on taxonomic classification.

Iterative Binning with MMLong2:

- Circular MAG Extraction: Identify and extract circular contigs as separate genome bins [5].

- Differential Coverage Binning: Incorporate read mapping information from multi-sample datasets to leverage abundance variations across samples [5].

- Ensemble Binning: Apply multiple binning algorithms (e.g., MetaBAT2, MaxBin2) to the same metagenome and consolidate results [5].

- Iterative Binning: Repeat the binning process on the unbinned contigs from the initial round to recover additional MAGs [5].

Quality Assessment and Dereplication:

- Assess MAG quality (completeness, contamination) using CheckM or similar tools.

- Dereplicate MAGs at species level (e.g., 95% average nucleotide identity) to create a non-redundant genome catalogue [5].

This protocol enables cost-effective recovery of high-quality microbial genomes from highly complex ecosystems, which remain an untapped source of biodiversity [5].

Data Analysis and Integration

Microbial Community Analysis

Alpha Diversity Analysis

Alpha diversity metrics describe species richness, evenness, or diversity within a single sample [27]. They are grouped into four complementary categories, each capturing different aspects of microbial communities [27].

Table: Essential Alpha Diversity Metrics for Microbiome Studies

| Category | Key Metrics | Biological Interpretation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Chao1, ACE, Observed ASVs | Estimates the total number of species (observed and unobserved) | Highly correlated with each other; Chao1 and ACE account for unobserved species [27]. |

| Dominance/Evenness | Berger-Parker, Simpson, ENSPIE | Measures the dominance of a few microbes over others | Berger-Parker is easily interpretable (proportion of the most abundant taxon) [27]. |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | Faith's PD | Incorporates evolutionary relationships between species | Depends on both the number of observed features and singletons [27]. |

| Information Theory | Shannon, Pielou's evenness | Combines richness and evenness based on entropy | All information metrics are strongly correlated as they use Shannon's entropy as a reference [27]. |

Practical Recommendations [27]:

- Report a comprehensive set of metrics from at least three categories (e.g., Observed ASVs, Berger-Parker, Faith's PD, Shannon) to capture different diversity aspects.

- Do not rely solely on rarefaction; calculate metrics with non-rarefied data to preserve information, but validate with rarefied datasets.

- Note that singletons (ASVs with only one read) are required for some metrics (e.g., Robbins), but are removed by DADA2.

Statistical Comparisons Between Communities

Comparing microbial communities requires specialized statistical approaches. The ∫-LIBSHUFF program calculates the integral form of the Cramér-von Mises statistic to determine whether differences in library composition are due to sampling artifacts or underlying biological differences [28].

Application Protocol:

- Input: A distance matrix generated by DNADIST (PHYLIP package) containing distances for comparisons between two or more 16S rRNA gene libraries [28].

- Method: The algorithm measures the number of sequences unique to one library when two libraries are compared across all phylogenetic levels [28].

- Interpretation: Small P-values for both comparisons (X vs. Y and Y vs. X) indicate strong evidence that neither library is a subset of the other, suggesting distinct communities [28].

Data Integration Strategies

Integrating microbiome data with other omics layers, such as metabolomics, is crucial for elucidating complex biological mechanisms. A comprehensive benchmark of nineteen integrative methods provides the following guidelines [29].

Table: Strategies for Integrating Microbiome and Metabolome Data

| Research Goal | Recommended Methods | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Global Associations | MMiRKAT, Mantel test | Determine the presence of an overall association between entire microbiome and metabolome datasets [29]. |

| Data Summarization | Redundancy Analysis (RDA), MOFA2 | Identify major trends and sources of variability that are shared across the two omic layers [29]. |

| Individual Associations | Sparse PLS (sPLS), Spearman correlation with multiple testing correction | Detect specific microbe-metabolite pairs that are significantly associated [29]. |

| Feature Selection | sparse CCA (sCCA), LASSO | Identify a minimal set of the most relevant microbial and metabolic features that drive the association [29]. |

Essential Preprocessing Considerations [29]:

- Compositionality: Properly handle microbiome compositionality using transformations like centered log-ratio (CLR) or isometric log-ratio (ILR).

- Data Structures: Account for over-dispersion, zero-inflation, and high collinearity inherent in microbiome data.

- Study Design: Control for confounders such as transit time, regional changes, and horizontal transmission in the study design and analysis.

Experimental Planning and Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA Kit | Standardized microbial DNA extraction | Ensize reproducible lysis of Gram-positive and negative bacteria |

| PBS Buffer | Sample dilution and homogenization | Maintains cellular integrity during processing |

| MagAttract PowerSoil DNA Kit | High-throughput DNA extraction | Ideal for soil and sediment samples with high inhibitor content |

| Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kits | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing | Standardized workflow for V3-V4 or V4 regions |

| PacBio SMRTbell Libraries | HiFi shotgun metagenomics | Enables long-read sequencing with high accuracy [26] |

| MetaPolyzyme Enzyme Mix | Mechanical and enzymatic lysis | Enhances DNA yield from difficult-to-lyse microorganisms |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Sample preservation | Stabilizes microbial community composition at time of collection |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for 16S rRNA and whole-genome shotgun metagenomics, highlighting their complementary nature in microbial ecology studies.

Data Visualization Guidelines

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting highly dimensional, sparse, and compositional microbiome data [30].

Table: Selection Guide for Microbiome Data Visualization

| Analysis Type | Sample-Level Plot | Group-Level Plot | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Diversity | Scatterplot | Box plot with jitters | Show individual data points to visualize distribution [30]. |

| Beta Diversity | Dendrogram, Heatmap | PCoA ordination plot | Use PCoA for overall variation between groups; dendrograms for sample relationships [30]. |

| Relative Abundance | Heatmap | Stacked bar chart, Pie chart | Aggregate rare taxa in bar charts to avoid overcrowding [30]. |

| Core Taxa | - | UpSet plot | Use UpSet plots instead of Venn diagrams for >3 groups [30]. |

| Microbial Interactions | Network plot | Correlogram | Highlight key associations and modular structure [30]. |

Optimization Tips [30]:

- Colors: Use consistent, color-blind friendly palettes (e.g., viridis) across all figures. Limit to 7 colors per graph.

- Labels: Add informative titles and axis labels. Label outliers or key features, but avoid overplotting.

- Ordering: Reorder categories by median, abundance, or user-defined order rather than alphabetically.

- Faceting: Split complex graphs into panels (e.g., by phylum) to improve readability.

The integration of 16S rRNA sequencing and whole-genome shotgun metagenomics provides a powerful framework for advancing microbial ecology research. While 16S rRNA profiling offers a cost-effective method for taxonomic profiling and diversity analyses, WGS metagenomics enables functional insights and genome-resolved metagenomics through MAG recovery [24]. The emergence of long-read sequencing technologies addresses previous limitations in studying complex environments, substantially expanding known microbial diversity and improving species-level classification [25] [5]. As these technologies continue to evolve, standardized workflows, appropriate statistical integration methods, and effective visualization practices will be essential for translating microbial ecology data into meaningful biological insights with applications in human health, environmental science, and biotechnology.

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies have revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling comprehensive study of microbial communities directly from their environments, bypassing the limitation that most environmental microbes cannot be cultivated in the laboratory [31] [32]. These culture-independent approaches, particularly shotgun metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing, allow researchers to simultaneously characterize taxonomic composition and functional potential of complex microbial ecosystems [31] [33]. The synergy between HTS, powerful computing hardware, and sophisticated bioinformatics software has transformed our understanding of microbial diversity, ecological interactions, evolutionary histories, and community metabolism [32]. This protocol outlines essential bioinformatics methodologies for processing sequencing data from raw reads through taxonomic classification and functional analysis, framed within the context of investigating microbial ecology using HTS technologies.

Metagenomic analyses generally follow two complementary approaches: read-based classification (useful when organisms have close relatives in reference databases) and assembly-based analysis (preferable for exotic environments with poorly represented organisms) [34]. A typical integrated workflow incorporates elements of both strategies to maximize insights into microbial community structure and function.

Table 1: Key Analysis Approaches in Metagenomics

| Approach | Description | Best Use Cases | Common Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read-Based Classification | Direct taxonomic and functional assignment of individual sequencing reads | Samples with good reference database representation; quick community profiling | Kaiju, DIAMOND, Kraken, MetaPhlAn [31] [34] |

| Assembly-Based Analysis | Reconstruction of genomic sequences from short reads before analysis | Discovering novel organisms; studying genomic context | MEGAHIT, SPAdes, IDBA-UD, MetaVelvet-SL [31] [34] |

| Binning | Grouping contigs or reads into biologically meaningful units | Reconstructing genomes from complex communities | CONCOCT, metaBAT, MaxBin [31] |

| Single-Cell Genomics | Sequencing genomes from individually isolated cells | Studying rare community members; reference genome creation | Single-cell genomic sequencing [31] |

Metagenomic Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the two primary analysis pathways (read-based and assembly-based) for processing microbial sequencing data, from raw reads through to biological interpretation.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Analysis

| Category | Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | fastp [34] | Adaptive read trimming and quality reporting | Preprocessing of raw sequencing data |

| Taxonomic Classification | Kaiju [33] [34] | Protein-based taxonomic assignment using translated reads | Sensitive taxonomy profiling |

| Alignment | DIAMOND [34] | Fast protein sequence alignment | Functional annotation against reference databases |

| Assembly | MEGAHIT [34] | Efficient metagenome assembly | Contig reconstruction from short reads |

| Workflow Management | Snakemake [33] [34] | Workflow automation and reproducibility | Pipeline execution and management |

| Reference Databases | NCBI nr [33] | Non-redundant protein sequence database | Taxonomic and functional reference |

| Reference Databases | Gene Ontology (GO) [33] | Functional term standardization | Functional annotation consistency |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Objective: Remove low-quality sequences and contaminants to ensure reliable downstream analysis.

Procedure:

- Quality Assessment: Run fastp on raw FASTQ files to generate quality reports. Examine key metrics including per-base sequence quality, sequence duplication levels, and adapter contamination [34].

- Read Trimming: Execute quality and adapter trimming with fastp using parameters:

--cut_front --cut_tail --cut_window_size 4 --cut_mean_quality 20[34]. - Host DNA Depletion: (Optional) For host-associated samples, align reads to host genome using Bowtie2 with sensitive parameters. Retain unmapped reads for subsequent analysis [33] [34].

- Post-processing QC: Verify trimming effectiveness by comparing pre- and post-trimming quality reports.

Technical Notes: The fastp tool processes input reads in a single pass, generating interactive HTML reports that include before-and-after filtering statistics [34].

Taxonomic Profiling Methods

Objective: Identify microbial community composition at various taxonomic ranks.

Reference-Based Taxonomic Classification

Procedure:

- Database Selection: Choose appropriate reference database based on sample type (e.g., Greengenes for 16S rRNA gene studies, NCBI nr for shotgun data) [31].

- Classification Execution: Run Kaiju using the

-tparameter to specify taxonomy nodes and-ffor reference database. For standard metagenomes:kaiju -t nodes.dmp -f nr_euk.fmi -i sample1.fastq -o sample1.kaiju.out[33] [34]. - Result Processing: Convert Kaiju outputs to abundance tables using Kaiju2table script, applying abundance filters (recommended: 0.001% cutoff) to remove likely false positives [33].

- Cross-Tool Validation: (Optional) Run complementary classification with MetaPhlAn or Kraken for method verification [31].

Reference-Free Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) Analysis

Procedure:

- Gene Targeting: For amplicon studies, select appropriate marker genes (16S rRNA for general composition; RuBisCO, amoA, soxB, mcrA for specific biogeochemical cycles) [31].

- Sequence Clustering: Use UCLUST or UPARSE to cluster sequences into OTUs at 97% similarity threshold [31].

- Chimera Removal: Apply UCHIME or ChimeraSlayer to filter artificial chimeras formed during PCR amplification [31].

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign taxonomy to representative sequences using RDP classifier or PhylOTU for phylogenetic placement of unclassified OTUs [31].

Technical Notes: Protein-based classification with Kaiju generally provides greater sensitivity for species-level identification compared to 16S rRNA-based methods, particularly for poorly characterized organisms [33].

Functional Annotation

Objective: Characterize metabolic potential and functional processes within microbial communities.

Procedure:

- Protein Identification: Align quality-filtered reads to NCBI nr database using DIAMOND with sensitive mode:

diamond blastx -d nr -q sample1_trimmed.fastq -o sample1.daa -f 100 --sensitive[34]. - Gene Ontology Mapping: Transfer functional annotations using custom SQLite database that maps protein accessions to GO terms [33].

- Abundance Quantification: Generate normalized counts for each GO term by summing proportional read counts across all proteins associated with each term [33].

- Functional Profile Analysis: Create sample-by-function abundance matrices for comparative analysis between experimental conditions.

Technical Notes: MetaFunc constructs a specialized SQLite database that consolidates GO annotations from all identical sequences in NCBI nr entries, ensuring comprehensive functional annotation coverage [33].

Metagenome Assembly and Binning

Objective: Reconstruct genomes from complex microbial communities without reference sequences.

Procedure:

- De Novo Assembly: Execute MEGAHIT with meta-large preset for complex communities:

megahit -1 sample1_R1.fastq -2 sample1_R2.fastq -o assembly_output --preset meta-large[34]. - Assembly Quality Assessment: Evaluate contig statistics (N50, contig counts) and check for chimeric sequences using appropriate validation tools [31].

- Sequence Binning: Group contigs into genome bins using composition-based tools (CONCOCT, metaBAT) with tetra-nucleotide frequency and coverage information [31].

- Bin Refinement: Integrate multiple binning approaches and use CheckM to assess genome completeness and contamination.

Technical Notes: Composition-based binning methods are computationally intensive but can be accelerated using matrix decomposition approaches like streaming singular value decomposition [31].

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis: This workflow illustrates the parallel processing of microbial and host-derived sequences in metatranscriptomic studies, enabling correlation analysis between host gene expression and microbial community function.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Statistical Analysis of Community Composition

Objective: Identify differentially abundant taxa and functions between experimental conditions.

Procedure:

- Data Normalization: Filter low-abundance features using

filterbyExprfunction in edgeR with minimum count threshold of 1 (user-adjustable) [33]. - Normalization Factor Calculation: Compute normalization factors using

calcNormFactorsin edgeR with default TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) method [33]. - Differential Analysis: Perform exact tests for pairwise comparisons between experimental groups using

exactTestin edgeR [33]. - Multiple Testing Correction: Apply Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction to p-values [33].

- Result Interpretation: Consider both statistical significance (FDR < 0.05) and biological relevance (fold-change > 2) when identifying important features.

Correlation Analysis Between Taxonomy and Function

Objective: Establish relationships between microbial taxa and functional processes.

Procedure:

- Data Integration: Merge taxonomic abundance tables with functional annotation tables using taxonomy IDs and protein accession numbers as keys [33].

- Correlation Calculation: Compute Spearman correlation coefficients between taxon abundances and functional term abundances.

- Network Visualization: Create bipartite networks linking taxa to functions using Cytoscape or specialized R packages.

- Biological Interpretation: Identify keystone taxa driving important metabolic processes and potential functional redundancies within communities.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Table 3: Common Bioinformatics Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low taxonomic classification rate | Reference database bias; novel organisms | Enrich with environmental sequences; use assembly-based approach [31] |

| Chimeric contigs in assembly | Misassembly of similar regions from different genomes | Apply composition-based binning; use coverage variation across samples [31] |

| Inconsistent functional annotations | Different reference databases or identifier systems | Use standardized mapping dictionaries; create custom SQLite databases [33] [34] |

| High computational demands | Large dataset size; memory-intensive algorithms | Use disk-based aligners (DIAMOND); implement streaming algorithms [31] [34] |

| Difficulty discriminating closely related species | Highly conserved marker genes | Combine multiple marker genes; use protein-level classification [31] [33] |

Applications in Microbial Ecology

The protocols described enable diverse applications in microbial ecology research. The STAMP (Sequence Tag-based Analysis of Microbial Populations) method, which utilizes genetically barcoded organisms, can quantify population bottlenecks and founding population sizes during infection, revealing host barriers to colonization and microbial dissemination patterns [35]. For human microbiome studies, the integration of host transcriptomic data with microbial functional profiling enables investigation of host-microbe interactions in conditions like colorectal cancer [33]. In environmental microbiology, these approaches help uncover the roles of microbial communities in biogeochemical cycling, symbiosis, and responses to environmental change [31] [32].

The bioinformatics workflows presented here provide a comprehensive framework for analyzing metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing data, from raw reads through taxonomic and functional interpretation. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, bioinformatics methods must similarly evolve to address new computational challenges and leverage the richer data structures provided by long-read sequencing and chromatin conformation capture technologies [31]. The integration of standardized, reproducible workflows like MEDUSA [34] and MetaFunc [33] with continuously updated reference databases will further enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from complex microbial communities, ultimately advancing our understanding of microbial ecology in diverse environments from the human body to global ecosystems.

From Sample to Insight: Practical HTS Workflows and Cutting-Edge Applications

Within microbial ecology research, high-throughput sequencing has revolutionized our capacity to decipher complex microbial communities. The reliability of these insights, however, is fundamentally dependent on the wet-lab protocols employed for DNA extraction and library preparation [36]. These initial steps are critical for determining the quantity, quality, and representativeness of the sequenced data, ultimately influencing all downstream ecological inferences. This application note provides detailed methodologies for key experiments, summarizing comparative data and outlining essential research reagents to support robust experimental design in microbial ecology.

Experimental Protocols

DNA Extraction Methods for Challenging Samples

The recovery of DNA from complex biological samples, particularly those that are ancient or environmentally challenging, requires specialized protocols optimized for short, fragmented DNA and the removal of co-extracted inhibitors [36].

Protocol 1: QG Extraction Method (Rohland and Hofreiter, 2007) This silica-based method is designed for efficient DNA release and inhibitor removal [36].

- Digestion: Incubate the biological sample (e.g., 50-100 mg of dental calculus or soil) in a digestion buffer containing EDTA and proteinase K for 12-24 hours at 55°C with constant agitation.

- Binding: Add a binding buffer containing a high concentration of guanidinium thiocyanate to the lysate. This facilitates the binding of DNA to silica.

- Purification: Transfer the mixture to a silica membrane column, centrifuge, and wash with a commercial buffer to remove contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the purified DNA in a low-EDTA Tris-HCl buffer or nuclease-free water.

Protocol 2: PB Extraction Method (Dabney et al., 2013) A modified silica-based protocol optimized for the recovery of ultra-short DNA fragments (<50 bp) [36].

- Digestion: Follow the same digestion step as the QG method.

- Binding: Use a binding buffer composed of sodium acetate, isopropanol, and guanidinium hydrochloride. This specific formulation enhances the binding efficiency of very short DNA fragments to the silica matrix.

- Purification and Elution: Perform purification and elution as described in the QG method.

Library Preparation Protocols for Ancient DNA (aDNA)

Library construction for aDNA research is typically based on Illumina sequencing and can be broadly classified into double-stranded and single-stranded methods [36].

Protocol 3: Double-Stranded Library (DSL) Preparation (Meyer and Kircher, 2010) This widely used protocol is effective for a range of sample types [36].

- End Repair: Repair the ends of the double-stranded DNA molecules using a combination of enzymes.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate double-stranded, blunt-ended adapters to the repaired DNA fragments.

- Indexing PCR: Amplify the adapter-ligated library using primers containing unique index sequences for sample multiplexing.

- Purification: Clean up the final library using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads to remove short fragments and reaction components.

Protocol 4: Single-Stranded Library (SSL) Preparation (Gansauge and Meyer, 2013) This method denatures DNA molecules to single-stranded form, potentially offering higher conversion efficiency of fragments into sequencer-compatible molecules [36].

- Denaturation: Heat the DNA extract to denature double-stranded molecules into single strands.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate specific adapters to the 3' and 5' ends of the single-stranded DNA molecules.

- Synthesis: Synthesize the complementary strand to create a double-stranded library molecule.

- Indexing and Purification: Amplify with indexing primers and purify as in the DSL protocol. The recently developed Santa Cruz Reaction (SCR) method is a streamlined SSL approach that reduces cost and processing time [36].

Metagenomic Sequencing and Binning for Complex Ecosystems

For highly complex environmental samples like soil, deep long-read sequencing and advanced binning are required to recover high-quality microbial genomes [5].

Protocol 5: mmlong2 Workflow for Terrestrial Metagenomes This workflow is designed for recovering prokaryotic metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from complex datasets [5].

- DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Extract DNA using a robust method (e.g., Protocol 1 or 2). Perform deep long-read sequencing (e.g., ~100 Gbp per sample on Nanopore platforms).

- Assembly and Polishing: Assemble sequence reads into contigs and perform iterative polishing to correct errors.

- Eukaryotic Contig Removal: Filter out contigs of eukaryotic origin to focus on prokaryotic MAGs.

- Iterative Binning: Recover MAGs using a multi-step binning strategy:

- Differential Coverage Binning: Incorporate read mapping information from multiple samples.

- Ensemble Binning: Apply multiple binning algorithms to the same metagenome.

- Iterative Binning: Repeatedly bin the metagenome to maximize MAG recovery.

Data Presentation

Impact of Wet-Lab Protocols on aDNA Recovery

Table 1: Comparative performance of DNA extraction and library preparation methods on archaeological dental calculus, based on [36].

| Metric | QG + DSL | QG + SSL | PB + DSL | PB + SSL | Impact on Data Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Fragment Recovery (<100 bp) | Moderate | Moderate | Good | Excellent | Affects total yield and ability to sequence highly degraded DNA. |

| Clonality | Higher | Moderate | Moderate | Lower | High clonality reduces complexity and can skew quantitative analyses. |

| Endogenous DNA Content | Varies with preservation | Varies with preservation | Varies with preservation | Varies with preservation | No single protocol is universally superior; depends on sample context. |

| Microbial Community Composition | Protocol-Dependent | Protocol-Dependent | Protocol-Dependent | Protocol-Dependent | Different protocols can recover different microbial profiles from the same sample. |

| Best for Sample Type | Well-preserved calculus | Well-preserved calculus | Poorly-preserved calculus | Poorly-preserved calculus | Effectiveness is modulated by the preservation state of the sample. |

MAG Recovery from Complex Terrestrial Habitats

Table 2: Genome recovery statistics from the Microflora Danica project using the mmlong2 workflow on 154 soil and sediment samples, based on [5].

| Parameter | Result | Ecological and Technical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sequenced Data | 14.4 Tbp | Demonstrates the depth of sequencing required to tap into complex terrestrial microbial diversity. |

| Median Reads per Sample | 94.9 Gbp | Highlights the high-throughput nature of the long-read sequencing approach. |

| Total MAGs Recovered (HQ+MQ) | 23,843 | Shows the potential for massive genome recovery from a single study. |

| Dereplicated Species-Level MAGs | 15,640 | Represents a substantial expansion of the known microbial tree of life. |

| Newly Described Genera | 1,086 | Underscores the vast amount of previously uncharacterized microbial diversity in terrestrial habitats. |

| Habitat with Highest MAG Yield | Coastal samples | Suggests ecological factors (e.g., salinity, nutrient levels) influence community structure and MAG recovery success. |

| Habitat with Lowest MAG Yield | Agricultural fields | Indicates that high nutrient input and management may increase microdiversity, complicating MAG assembly. |

Workflow Visualization

End-to-End Ancient Metagenomics Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key decision points and steps in a typical ancient DNA metagenomics study, from sample to analysis [36].

Advanced Binning Strategy for Complex Metagenomes

The mmlong2 workflow employs a multi-faceted binning strategy to maximize the recovery of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from highly complex environmental samples like soil [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing in microbial ecology.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic digestion of proteins in the sample to release DNA. | Standard step in both QG and PB DNA extraction protocols [36]. |

| Guanidinium Salts | Component of binding buffer; a chaotropic agent that disrupts molecular structures, facilitating DNA binding to silica. | Guanidinium thiocyanate (QG protocol) and guanidinium hydrochloride (PB protocol) [36]. |

| Silica Membranes/Matrices | Solid phase for DNA binding and purification during extraction, allowing contaminants to be washed away. | Used in column-based purification in both QG and PB methods [36]. |

| Double-Stranded DNA Adapters | Short, known DNA sequences ligated to fragmented DNA, enabling amplification and sequencing on Illumina platforms. | Used in the DSL protocol for ancient and modern DNA [36]. |

| Single-Stranded DNA Adapters | Specialized adapters designed for ligation to single-stranded DNA templates. | Critical for SSL protocols, offering potentially higher efficiency for degraded samples [36]. |

| SPRI Beads | Solid-phase reversible immobilization beads used for size selection and purification of DNA libraries. | Clean-up step after adapter ligation and PCR in library preparation [36]. |

| Nanopore Flow Cells | The consumable containing nanopores for performing long-read sequencing (e.g., PromethION). | Key for generating the long reads needed for the mmlong2 workflow on complex soils [5]. |

Microbial community profiling has become a cornerstone of modern microbial ecology, enabling researchers to decipher the complex composition and functional capabilities of microbiomes in diverse environments such as soil, the human gut, and the respiratory tract. Advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies have revolutionized our ability to study these communities in a culture-independent manner, providing unprecedented insights into their diversity, dynamics, and interactions [37].

This application note outlines standardized protocols for microbial community profiling using amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics, framed within the context of a broader thesis on high-throughput sequencing for microbial ecology research. The content is specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require robust, reproducible methods for microbiome analysis. We present detailed methodologies, experimental workflows, and key reagent solutions to support comprehensive microbial community characterization across different sample types.

Key Concepts and Profiling Approaches

Microbial community profiling aims to answer two fundamental questions: "Who is there?" and "What are they doing?" [38]. Several sequencing approaches address these questions at different levels of resolution and for different applications.