Strategies for Parameter Optimization in Metagenomic Sequence Assembly: Enhancing Genome Recovery for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing parameters for metagenomic sequence assembly, a critical step in unlocking the functional potential of microbial communities.

Strategies for Parameter Optimization in Metagenomic Sequence Assembly: Enhancing Genome Recovery for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing parameters for metagenomic sequence assembly, a critical step in unlocking the functional potential of microbial communities. It covers foundational principles, from initial study design and sampling to the selection of sequencing technologies. The content delves into modern algorithmic approaches, including long-read assemblers and co-assembly strategies, and offers practical troubleshooting for common challenges like host DNA contamination and strain diversity. By comparing assembly performance and validation frameworks, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to generate high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), thereby advancing discoveries in microbial ecology, antibiotic resistance, and human health.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Project Design for Effective Assembly

The Impact of Habitat Selection and Characterization on Assembly Outcomes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is meant by "habitat selection" in the context of metagenomic assembly? In metagenomics, "habitat selection" refers to the bioinformatic process of selectively characterizing and filtering sequencing data from complex microbial communities to improve assembly outcomes. This involves using specific parameters and tools to target genomes of interest from environmental samples, much like organisms select optimal habitats based on environmental cues. Advanced simulators like Meta-NanoSim can characterize unique properties of metagenomic reads, such as chimeric artifacts and error profiles, allowing researchers to selectively optimize assembly parameters for specific microbial habitats [1].

2. How does read characterization impact metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) quality? Proper read characterization directly influences MAG quality by enabling more accurate parameter optimization. Key characterization steps include assessing read length distributions, error profiles, chimeric read content, and microbial abundance levels. This characterization allows researchers to select appropriate assembly algorithms and parameters specific to their sequencing technology and sample type, ultimately affecting the completeness and contamination levels of resulting MAGs. High-quality MAGs should have a CheckM or CheckM2 completeness of at least 90% and be under 5% contamination [2] [3].

3. What are the minimum quality thresholds for submitting MAGs to public databases? NCBI requires MAGs to meet specific quality standards before submission:

- CheckM or CheckM2 completeness ≥90%

- Total assembly size ≥100,000 nucleotides

- Representation of a single prokaryotic or eukaryotic organism

- Inclusion of all identified genome sequence (no selective removal of noncoding regions) [2]

4. Can I submit assemblies without annotation to public databases? Yes, you can submit genome assemblies without any annotation to NCBI databases. However, during the submission process, you may request that prokaryotic genome assemblies be annotated by NCBI's Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) before release into GenBank [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor MAG Quality and High Contamination

Symptoms:

- CheckM completeness below 90%

- CheckM contamination above 5%

- Unusual genome size or GC content

- Multiple single-copy marker genes present in unexpected numbers

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient binning quality | Apply multiple binning tools and use consensus approaches; tools like MetaWrap provide superior binning algorithms [4]. | Perform binning optimization on control datasets before analyzing experimental data. |

| Contaminant sequences in assembly | Use tetranucleotide frequency, GC content, and coding density to identify and remove contaminant contigs [3]. | Implement rigorous quality filtering of raw reads before assembly. |

| Mis-assembled contigs | Evaluate read coverage uniformity across contigs; break contigs at regions with dramatic coverage changes. | Use hybrid assembly approaches combining long and short reads [5]. |

| Horizontal gene transfer regions | Annotate contigs and identify genes with atypical phylogenetic origins. | Consider evolutionary relationships when interpreting results. |

Problem 2: Suboptimal Assembly Metrics

Symptoms:

- Low N50 values

- Highly fragmented assemblies

- Large numbers of short contigs

- Poor recovery of complete genes

Diagnostic Strategy:

- Check read quality metrics (Q scores, adapter content)

- Evaluate raw read length distribution

- Assess community complexity (alpha diversity)

- Verify sequencing depth coverage

Optimization Approaches:

| Parameter | Adjustment | Expected Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing depth | Increase to 20-50x for target organisms | Improved contiguity, better binning |

| Read length | Utilize long-read technologies (ONT, PacBio) | Spanning repetitive regions, reduced fragmentation |

| Assembly algorithm | Test multiple assemblers (metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT) | Algorithm-specific performance variations |

| k-mer sizes | Optimize for specific community composition | Better resolution of strain variants |

Case Example: A study optimizing viral metagenomic assembly found that combining optimized short-read (15 PCR cycles) and long-read sequencing approaches enabled identification of 151 high-quality viral genomes with high taxonomic and functional novelty from fecal specimens [5].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Metagenomic Read Characterization Using Meta-NanoSim

Purpose: To characterize Oxford Nanopore metagenomic reads for error profiles, chimeric content, and abundance estimation to inform assembly parameter optimization.

Materials:

- Oxford Nanopore metagenomic reads in FASTQ format

- Reference metagenome (if available)

- Meta-NanoSim software (within NanoSim version 3+)

Procedure:

- Install Meta-NanoSim: Download from https://github.com/bcgsc/NanoSim

- Characterization Phase:

- Input: Raw metagenomic reads and reference metagenome

- Process: Align reads to reference to infer ground truth

- Output: Statistical models of read length distributions, error profiles, chimeric reads, and abundance levels

- Simulation Phase:

- Apply pretrained models to simulate complex microbial communities

- Input: List of reference genomes, target abundance levels, genome topologies

- Output: Simulated datasets with characteristics true to experimental data

Application: Use characterized models to determine optimal assembly parameters and predict performance of different binning approaches [1].

Protocol 2: Complete Metagenomic Analysis Workflow

Purpose: To provide an end-to-end workflow for habitat characterization and assembly optimization.

Materials:

- Metagenomics-Toolkit (https://github.com/metagenomics/metagenomics-tk)

- High-performance computing resources (cloud or cluster)

- Raw metagenomic reads (Illumina and/or Oxford Nanopore)

Procedure:

- Quality Control:

- Adapter trimming, quality filtering, host sequence removal

- Generate quality reports for each sample

- Assembly:

- Execute machine learning-optimized assembly with RAM prediction

- Perform both single-sample and co-assembly approaches

- Binning:

- Apply multiple binning algorithms

- Generate consensus bins

- Annotation:

- Functional annotation of predicted genes

- Taxonomic classification

- Cross-sample Analysis:

- Dereplication of genomes across samples

- Co-occurrence analysis

- Metabolic modeling of community interactions

Note: The Metagenomics-Toolkit is optimized for cloud-based execution and can handle hundreds to thousands of samples efficiently [4].

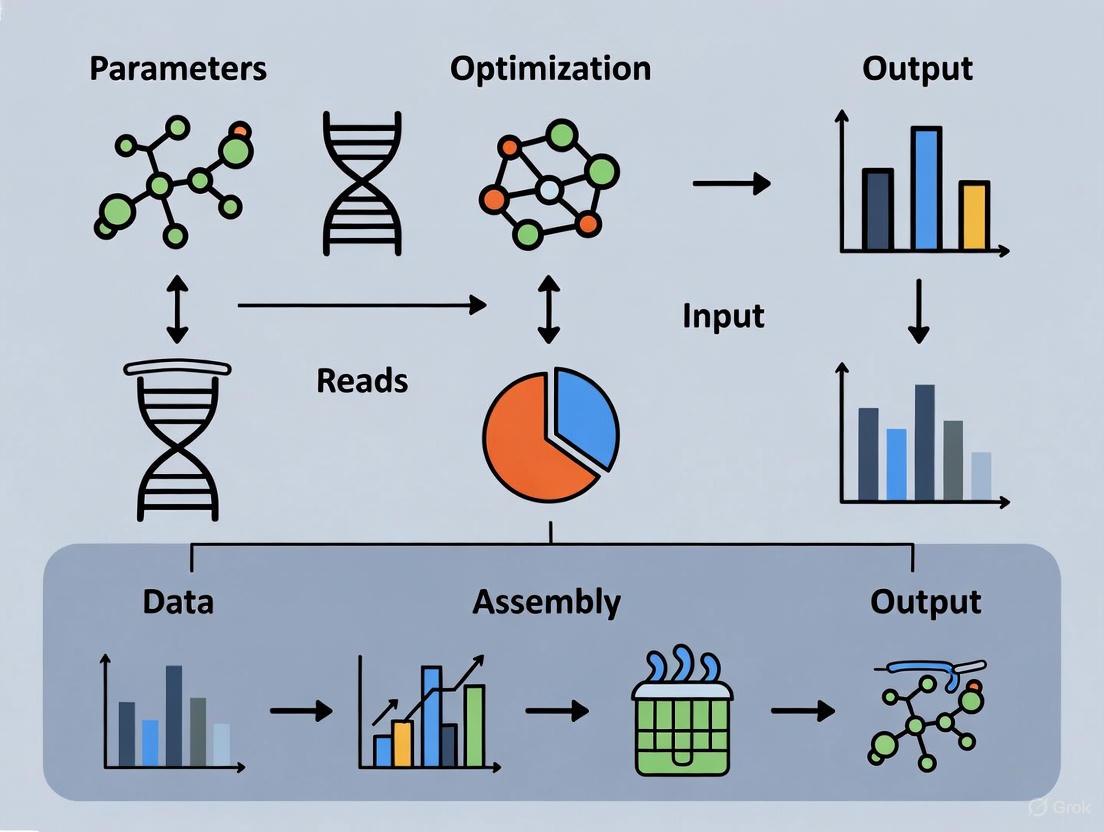

Workflow Visualization

Metagenomic Analysis Workflow

Quality Control Decision Matrix

Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource | Function | Application in Habitat Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Meta-NanoSim | Characterizes and simulates nanopore metagenomic reads | Models read properties specific to metagenomics before actual assembly [1] |

| Metagenomics-Toolkit | End-to-end workflow for metagenomic analysis | Provides standardized processing from raw reads to MAGs with optimized resource usage [4] |

| NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) | Automated annotation of prokaryotic genomes | Provides consistent annotation for assembled genomes before database submission [2] |

| CheckM/CheckM2 | Assesses completeness and contamination of MAGs | Quality control for habitat selection outcomes [2] |

| BioProject/BioSample Registration | NCBI metadata organization | Essential for contextualizing assembly outcomes with sample habitat information [6] |

| Table2asn | Converts annotation data to ASN format | Prepares annotated assemblies for NCBI submission [2] |

Designing a Robust Sampling Strategy to Account for Community Variability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most crucial step in a metagenomic study to ensure reliable results? The most crucial step is sample processing and DNA extraction. The DNA extracted must be representative of all cells present in the sample, and the method must provide sufficient amounts of high-quality nucleic acids for subsequent sequencing. Non-representative extraction is a major source of bias, especially in complex environments like soil, where different lysis methods (direct vs. indirect) can significantly alter the perceived microbial diversity and DNA yield [7].

FAQ 2: How can I optimize sampling for low-biomass environments, like hospital surfaces? For low-biomass samples, a robust strategy involves:

- Pooling Samples: Aggregating multiple swabs from similar sites to increase total biomass [8].

- High-Yield DNA Extraction: Using bead beating and heat lysis followed by liquid-liquid extraction instead of common column-based kits, which may recover no detectable DNA [8].

- Biomass Assessment: Correlating DNA yield with expected sequencing output; for example, an input greater than 11.2 ng of DNA was correlated with generating over 100,000 raw reads in one study [8].

FAQ 3: My sample has a high proportion of host DNA. How can I enrich for microbial targets? When the target community is associated with a host (e.g., plant or invertebrate), you can use:

- Fractionation: Physical separation of microbial cells from host material.

- Selective Lysis: Using chemical or enzymatic treatments that preferentially lyse microbial cells without disrupting host cells. This is critical when a large host genome could overwhelm the microbial signal in sequencing, making it difficult to detect microbes [7].

FAQ 4: What are the key parameters to consider when choosing a sequencing technology for metagenomics? Your choice involves a trade-off between read length, accuracy, cost, and throughput. Key parameters are summarized in the table below [7] [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Technologies for Metagenomics

| Technology | Typical Read Length | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (SBS) | 50-300 bp | Very high accuracy (99.9%), high throughput, low cost per Gbp [9] | Short read length complicates assembly in repetitive regions [10] | High-resolution profiling of complex communities [7] |

| 454/Roche (Pyrosequencing) | 600-800 bp | Longer read length improves assembly, lower cost than Sanger [7] | High error rate in homopolymer regions, leading to indels [7] | Now largely obsolete, but historically important for metagenomics |

| PacBio (SMRT) | 10-15 kbp | Very long reads, excellent for resolving repeats and complex regions [9] | Lower single-read accuracy (87%) [9] | High-quality assembly and finishing genomes [10] |

| Oxford Nanopore | 5-10 kbp | Long reads, portable sequencing devices [9] | Lower accuracy (70-90%) [9] | Assembling complex regions and real-time fieldwork [10] |

FAQ 5: How do I select the right assembler for my metagenomic data? The choice depends on your data type (read length, error profile) and computational resources. The main assembly paradigms each have strengths and weaknesses [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Metagenomic Assembly Algorithms

| Assembly Paradigm | Prototypical Tools | Advantages | Disadvantages | Effect of Sequencing Errors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greedy | TIGR, Phrap | Simple, intuitive, easy to implement [9] | Locally optimal choices can lead to mis-assemblies [9] | Highly affected [9] |

| Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) | Celera Assembler, Arachne | Effective with high error rates and long reads [9] | Computationally intensive, scales poorly with high coverage [9] | Less affected [9] |

| De Bruijn Graph | Velvet, SOAPdenovo, MEGAHIT, MetaSPAdes | Computationally efficient, works well with high coverage and low-error data [7] [9] | Graph structure is fragmented by sequencing errors [9] | Highly affected [9] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inadequate DNA Yield from Low-Biomass Samples

Problem: DNA concentration is below the detection limit or insufficient for library preparation. Solution:

- Switch DNA Extraction Methods: Replace column- or magnetic bead-based kits with a bead beating and heat lysis protocol followed by liquid-liquid extraction, which can increase yield from undetectable to sufficient levels (e.g., ~18 ng/μL) [8].

- Sample Pooling: If applicable, pool multiple sample swabs or wipes from equivalent sites to increase starting material [8].

- Whole-Cell Filtration (Use with Caution): Implement filtration to remove abiotic debris and eukaryotic cells if they constitute a large proportion of the sample. Note that this can cause a 13-44% biomass loss and may not be necessary if the non-bacterial fraction is small (~1%) [8].

- DNA Amplification (Last Resort): Use Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) with phi29 polymerase. Caution: This method can introduce biases, chimera formation, and amplify contaminating DNA, which can significantly impact community analysis [7].

Issue 2: Assembly is Highly Fragmented or Fails

Problem: The assembly process produces many short contigs instead of long, contiguous sequences. Solution:

- Check and Pre-process Reads: Ensure rigorous quality control and adapter trimming using tools like

fastporTrim_Galoreto remove low-quality bases and technical sequences that disrupt assembly [11]. - Increase Read Length: Consider using long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) or hybrid approaches that combine long reads for scaffolding with short reads for accuracy. This is particularly effective for resolving repetitive genomic regions [9] [10].

- Select an Appropriate Assembler: Match the assembler to your data.

- Normalize Reads: Use read normalization tools to reduce the redundancy of high-coverage regions, which can decrease memory usage and improve assembly continuity [12].

- Try Sequential Co-assembly: For multiple related samples, a sequential co-assembly approach can reduce the assembly of redundant reads, save computational resources, and produce fewer assembly errors compared to a traditional one-step co-assembly of all samples [13].

Issue 3: High Contamination in Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs)

Problem: Binned genomes have high contamination levels, indicated by tools like CheckM.

Solution:

- Use Multiple Binning Strategies: Employ a combination of binning algorithms that use different principles (e.g., composition-based

MetaBAT2, coverage-basedMaxBin2) and then consolidate the results using a hybrid tool likeDAS Toolto obtain the highest quality bins [10]. - Refine Bins: Use refinement tools like

MetaWRAPorAnvi'oto manually inspect and curate bins, removing contigs that are clear outliers in tetranucleotide frequency or coverage [10]. - Apply Quality Standards: Adhere to community standards for MAG quality, such as the "90% completeness and <5% contamination" threshold for a high-quality draft MAG [10].

Issue 4: Taxonomic Profiling Results are Inaccurate or Lack Resolution

Problem: The taxonomic classification of reads does not match expected community composition (based on mock communities) or fails to distinguish closely related species. Solution:

- Benchmark Pipelines: Use mock community samples with known compositions to test the accuracy of different taxonomic profilers. Recent unbiased benchmarks can guide tool selection [14].

- Choose a Modern Profiler: Select a pipeline that has demonstrated high accuracy. For example,

bioBakery4(which usesMetaPhlAn4) performed well in recent assessments because it incorporates metagenome-assembled genomes into its classification scheme, improving resolution [14]. - Understand Tool Types:

- k-mer-based (e.g.,

Kraken2): Fast, low computational cost, but lower detection accuracy and no gene detection [15]. - Marker-based (e.g.,

MetaPhlAn): Quick and efficient, but relies on a set of marker genes and can introduce bias [15]. - Alignment-based (e.g.,

DIAMOND): More computationally intensive but can provide higher accuracy, especially for novel sequences [15].

- k-mer-based (e.g.,

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Robust DNA Extraction for Low-Biomass Environmental Samples

Objective: To maximize DNA yield and representativeness from swab samples collected in low-biomass environments (e.g., hospital surfaces) [8].

Reagents and Materials:

- Sample swabs (e.g., synthetic tip swabs)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Lysozyme solution

- Proteinase K

- SDS lysis buffer

- Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1)

- Isopropanol

- 70% Ethanol

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Elution: Place the swab head in a tube containing 1-2 mL of PBS and vortex vigorously to elute material.

- Cell Lysis:

- Centrifuge the suspension to pellet cells. Discard the supernatant.

- Resuspend the pellet in a lysozyme solution and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Add Proteinase K and SDS to a final concentration of 100 µg/mL and 1% (w/v), respectively. Incubate at 56°C for 2 hours with gentle agitation.

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction:

- Add an equal volume of Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol to the lysate. Mix thoroughly by inversion.

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes to separate phases.

- Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube.

- DNA Precipitation:

- Add 0.7 volumes of isopropanol to the aqueous phase and mix gently. Incubate at -20°C for 1 hour.

- Centrifuge at >12,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet DNA.

- Wash the pellet with 1 mL of 70% ethanol. Centrifuge again and carefully discard the ethanol.

- Air-dry the pellet for 5-10 minutes and resuspend in nuclease-free water.

- Quantification: Quantify DNA using a fluorescence-based assay (e.g., Qubit) due to its high sensitivity and specificity for DNA.

Protocol 2: Evaluating and Optimizing Metagenomic Assembly Parameters

Objective: To systematically test different assemblers and parameters to achieve the most complete and least fragmented assembly [9] [12].

Reagents and Materials:

- High-quality trimmed metagenomic reads (FASTQ format)

- Computational cluster or high-performance computer with sufficient memory (≥ 128 GB RAM recommended for complex communities)

Software Tools:

- Quality control:

fastp[11] - Assemblers:

MEGAHIT(k-mer based),metaSPAdes(k-mer based),Flye(for long reads) [10] [12] - Assembly evaluator:

QUAST[12]

Procedure:

- Read Pre-processing: Run

fastpwith default parameters to perform quality trimming, adapter removal, and generate a quality control report. - Assembly with Multiple Tools:

- Run at least two different assemblers (e.g.,

MEGAHITandmetaSPAdes) on the pre-processed reads using their default parameters. - For

MEGAHIT, you might test different k-mer ranges (e.g.,--k-list 27,47,67,87).

- Run at least two different assemblers (e.g.,

- Evaluate Assembly Quality: Run

QUASTon the resulting contig files (contigs.fa). Key metrics to compare include:- Total contigs: The total number of contigs produced (fewer is better).

- Largest contig: The length of the largest contig (longer is better).

- N50 length: The contig length at which 50% of the total assembly is contained in contigs of that size or larger (higher is better).

- Total length: The sum of all contig lengths.

- Select the Best Assembly: Choose the assembly that maximizes N50 and total length while minimizing the total number of contigs. This assembly is then used for downstream binning and gene prediction.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a robust end-to-end workflow for metagenomic analysis, integrating sampling, sequencing, assembly, and binning strategies discussed in the FAQs and protocols.

Diagram Title: Robust Metagenomic Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Workflows

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Liquid Extraction Reagents | Maximizes DNA yield from difficult, low-biomass samples by separating DNA into an aqueous phase from a complex lysate using phenol-chloroform [8]. | Recovering detectable DNA from hospital surface swabs where column-based kits fail [8]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | A viability dye that penetrates only membrane-compromised (dead) cells and covalently cross-links their DNA upon light exposure, preventing its amplification [8]. | Differentiating between viable and non-viable microorganisms in an environmental sample during DNA sequencing [8]. |

| Internal Standard Spikes | Known quantities of synthetic or foreign DNA (e.g., from a non-native microbial community) added to a sample prior to DNA extraction [8]. | Quantifying absolute microbial abundances and correcting for technical biases and losses during sample processing [8]. |

| Mock Microbial Communities | Defined mixes of microbial cells or DNA with known composition and abundance, used as a positive control [14]. | Benchmarking and validating the accuracy of entire wet-lab and computational workflows, especially taxonomic profilers [14]. |

| Bead Beating Matrix | Micron-sized beads used in conjunction with a homogenizer to mechanically disrupt tough cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, spores) [8]. | Ensuring representative lysis of all cell types in a complex environmental sample like soil during DNA extraction [7]. |

FAQs on DNA Extraction in Metagenomic Research

What is the single largest source of variability in metagenomic studies, and how can it be controlled? DNA extraction has been identified as the step that contributes the most experimental variability in microbiome analyses [16]. This variability stems from the lysis method, reagent contamination, and personnel differences. To control this, implement these minimum standards:

- Detailed Reporting: Document all DNA extraction procedures for reproducibility.

- Use of Controls: Include positive controls (e.g., mock communities) and negative controls (extraction blanks) in every batch to monitor accuracy and contamination [17] [16].

- Protocol Consistency: Use the same DNA extraction protocol across all samples within a study, especially in multi-site projects where data will be pooled [16].

How does the choice of lysis method affect the representativeness of a metagenome? The lysis method is critical for breaking open different microbial cell walls. Incomplete lysis leads to under-representation of certain taxa.

- Mechanical Lysis (Bead Beating): Essential for effective lysis of Gram-positive bacteria, which have tough peptidoglycan layers in their cell walls. Methods using bead beating provide stable and high DNA yields and are superior for representing the full taxonomic diversity, including Gram-positive organisms [18] [19].

- Chemical/Enzymatic Lysis: These gentler methods can be insufficient for robust Gram-positive bacteria, leading to a biased community profile that over-represents easily-lysed Gram-negative bacteria [19].

Why are negative controls and "kitome" profiling so important, especially for low-biomass samples? Laboratory reagents and DNA extraction kits themselves contain trace amounts of microbial DNA, known as the "kitome" [17] [18].

- Impact: This contaminating DNA can be a significant source of false positives, which is particularly detrimental when sequencing low-biomass samples (e.g., tissue, blood, or water from sparsely-populated environments) where the signal from contaminants can overwhelm the true signal [17] [16].

- Solution: Process extraction blanks (using molecular-grade water) alongside your samples. The resulting sequencing data defines your "kitome," allowing for computational subtraction of these contaminants during bioinformatic analysis [17] [18].

How do I balance DNA yield and purity with representativeness for a complex environmental sample? There is often a trade-off, and the optimal balance depends on your sample type and downstream application.

- High Yield/Purity Kits: Kits designed with "Inhibitor Removal Technology" (e.g., QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro) are excellent for removing humic acids and other PCR inhibitors from complex matrices like soil, sediment, and wastewater, resulting in high-purity DNA [18] [20].

- Representative Lysis: These same kits, which incorporate a mechanical beating step, also ensure the lysis of tough cells, providing a more representative profile [19]. Therefore, for complex environmental samples, a kit that combines inhibitor removal with mechanical lysis is often the best choice for balancing all three parameters [20] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low DNA Yield

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incomplete cell lysis | Increase bead-beating time or agitation speed. Use a more aggressive lysing matrix (e.g., a mix of different bead sizes) [21]. |

| Sample is old or degraded | Use fresh samples where possible. For blood, use within a week or add DNA stabilizers to frozen samples to inhibit nuclease activity [21]. |

| Clogged spin filters | Pellet protein precipitates by centrifuging samples post-lysis before loading the supernatant onto the spin column [21]. |

| Insufficient starting material | Increase the volume or weight of the starting sample, if possible [21]. |

Problem: Poor DNA Purity (Inhibitors Present)

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Co-purification of inhibitors | Use a kit specifically designed for your sample type (e.g., soil kits for humic acids). Ensure all wash steps are performed thoroughly [18] [20]. |

| High host DNA contamination | For samples like blood or tissue, use kits that include a host DNA depletion step (e.g., benzonase treatment) [18] [16]. |

| High hemoglobin content in blood | Extend the lysis incubation time by 3-5 minutes to improve purity [21]. |

Problem: Non-Representative Community Profile

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inefficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria | Switch to a protocol that includes mechanical lysis via bead beating. This is the most critical step for lysing tough cells [19]. |

| Biases from different kit chemistries | Do not change DNA extraction kits mid-study. If comparing across studies, be aware that different kits will yield different community structures [18] [16]. |

| Loss of low-abundance taxa | Some kits are better at preserving rare species. The QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit, for instance, has been noted for minimal losses of low-abundance taxa [19]. |

Comparative Data from Experimental Studies

The following table summarizes key findings from published benchmarking studies that evaluated different DNA extraction methods across various sample types.

Table 1: DNA Extraction Method Performance Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Top-Performing Method(s) | Key Performance Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poultry Feces (for C. perfringens detection) | Spin-column (SC) and Magnetic Beads (MB) | Yielded DNA of higher purity and quality. SC was superior for LAMP and PCR sensitivity. Hotshot (HS) was most practical for low-resource settings. | [22] |

| Marine Samples (Water, Sediment, Digestive Tract) | Kits with bead beating and inhibitor removal (e.g., QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro) | Effective removal of PCR inhibitors (e.g., humic acids) and representative lysis of diverse bacteria, leading to higher alpha-diversity. | [18] |

| Piggery Wastewater (for pathogen surveillance) | Optimized QIAGEN PowerFecal Pro | Most suitable and reliable method, providing high-quality DNA effective for Oxford Nanopore sequencing and accurate pathogen detection. | [20] |

| Human Feces (for gut microbiota) | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit & AmpliTest UniProb + RIBO-prep | Best results in terms of DNA yield. QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit showed minimal losses of low-abundance taxa. | [19] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and kits referenced in the troubleshooting guides and comparative studies, with their primary functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Kits for DNA Extraction

| Reagent/Kit Name | Primary Function | Key Feature / Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | DNA purification from complex samples | Bead beating for mechanical lysis and inhibitor removal technology for high purity from soils, feces, and wastewater [18] [20] [19]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control | Positive process control | Known mock community spiked into samples to monitor extraction efficiency and sequencing accuracy [17]. |

| Inhibitor Removal Technology (e.g., in Qiagen kits) | Removal of PCR inhibitors | Specialized buffers to remove humic acids, pigments, and other contaminants common in environmental samples [18]. |

| Benzonase | Host DNA depletion | Enzyme that degrades host (e.g., human) DNA while leaving bacterial DNA intact, useful for low-microbial-biomass samples [18]. |

| EDTA | Anticoagulant & nuclease inhibitor | Prevents coagulation of blood samples and chelates metals to inhibit DNase activity [21]. |

| Proteinase K | Protein digestion | Degrades proteins and inactivates nucleases during the lysis step, increasing yield and purity [20] [21]. |

Workflow Diagram for Optimization Strategy

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for optimizing and troubleshooting DNA extraction to achieve a balanced output.

Contaminant Identification and Removal Pathway

This diagram illustrates the pathway for identifying and accounting for contamination using controls, a critical step for ensuring data integrity.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary technical differences between PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing?

The core difference lies in their underlying biochemistry and data generation. PacBio HiFi uses a method called Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS). In this process, a single DNA molecule is sequenced repeatedly in a loop, and the multiple passes are used to generate a highly accurate consensus read, known as a HiFi read [23] [24]. In contrast, ONT sequencing measures changes in an electrical current as a single strand of DNA or RNA passes through a protein nanopore [25]. This method sequences native DNA and can produce ultra-long reads, but the raw signal requires computational interpretation (basecalling) to determine the sequence [25] [23].

2. For a metagenomic assembly project with high species diversity, which technology is more suitable?

For highly diverse metagenomic samples, ONT's longer read lengths can be advantageous. Long and ultra-long reads (exceeding 100 kb) are more likely to span repetitive regions and complex genomic structures that are challenging to assemble with shorter fragments [26]. This capability was pivotal in achieving the first telomere-to-telomere assembly of the human genome [26]. However, if your research goals require high single-read accuracy to distinguish between very closely related strains or to detect rare variants, PacBio HiFi may provide more reliable base-calling from the outset [23] [27].

3. How do the error profiles of HiFi and ONT data differ, and how does this impact assembly?

The two technologies exhibit distinct error profiles, which influences the choice of assembly and error-correction algorithms.

- PacBio HiFi: Errors are primarily stochastic (random) and are drastically reduced through the circular consensus process, resulting in a very low final error rate [23].

- Oxford Nanopore: Errors are more systematic, with a known bias in homopolymeric regions (stretches of the same base, like "AAAAA"), where the technology can miscall the number of bases [23]. Recent hardware (R10 chips) and basecalling algorithms (e.g., Bonito, Guppy) have significantly improved accuracy in these regions [23] [28]. Specialized tools like DeChat have been developed specifically for repeat- and haplotype-aware error correction of ONT R10 reads [28].

4. What are the key considerations for sample preparation for these long-read technologies?

Successful long-read sequencing, regardless of the platform, is critically dependent on High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA [29] [30]. To preserve long DNA fragments, use gentle extraction kits designed for HMW DNA, avoid vigorous pipetting or vortexing, and assess DNA quality using pulsed-field electrophoresis systems like the Agilent Femto Pulse to confirm fragment size [29] [30]. For ONT in particular, specific library prep kits (e.g., Ligation, Rapid, Ultra-Long DNA Sequencing) can be selected to optimize for the desired read length [26].

5. When is it beneficial to use HiFi or ONT over short-read technologies like Illumina?

Long-read technologies are indispensable when the research question involves:

- De novo genome assembly: Long reads provide the continuity needed to assemble across repetitive regions and generate more complete genomes [25] [26].

- Structural Variant (SV) detection: Long reads can span large insertions, deletions, and rearrangements that are invisible to short-read technologies [26] [30].

- Full-length transcript sequencing: They enable the sequencing of entire RNA transcripts from end to end, allowing for the precise identification of splicing isoforms [30].

- Phasing: Long reads can determine whether genetic variants (like SNPs) are located on the same chromosome (in phase), which is crucial for haplotype reconstruction [24].

Technology Comparison at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core performance characteristics of PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore sequencing platforms to aid in direct comparison.

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications of PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore Sequencing

| Feature | PacBio HiFi Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Read Length | 15,000 - 20,000+ bases [25] | 20,000 bases to > 4 Megabases (ultra-long) [25] [26] |

| Raw Read Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30) [25] [24] | ~98% (Q20) with recent chemistry & basecalling [25] [28] |

| Primary Error Type | Stochastic (random) errors [23] | Systematic errors, particularly in homopolymer regions [23] |

| Typical Run Time | ~24 hours [25] | ~72 hours [25] |

| DNA Modification Detection | 5mC, 6mA (on-instrument) [25] | 5mC, 5hmC, 6mA (requires off-instrument analysis) [25] |

| Portability | Benchtop systems | Portable options available (MinION) [25] |

| Data Output File Size (per flow cell) | ~30-60 GB (BAM) [25] | ~1300 GB (FAST5/POD5) [25] |

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Proper experimental execution relies on high-quality starting materials and specialized kits. The following table lists key reagents and their functions for long-read sequencing projects.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Long-Read Sequencing

| Item | Function / Application | Example Kits / Products |

|---|---|---|

| HMW DNA Extraction Kit | To gently isolate long, intact DNA fragments from samples, minimizing shearing. | Nanobind HMW DNA Extraction Kit, NEB Monarch HMW DNA Extraction Kit [30] |

| PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kit | Prepares DNA libraries for PacBio sequencing by ligating hairpin adapters to create circular templates. | SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 [27] |

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit | The standard ONT kit for DNA sequencing where the read length matches the input DNA fragment length. | Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSKxxx) [26] |

| ONT Ultra-Long DNA Sequencing Kit | A specialized kit for generating reads >100 kb, ideal for resolving complex repeats. | Ultra-Long DNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-ULKxxx) [26] |

| DNA Size/Quality Assessment | To accurately determine the fragment size distribution and integrity of HMW DNA. | Agilent Femto Pulse System [30] |

Experimental Workflow for Technology Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate sequencing technology based on your primary research objective.

Decision Workflow for Selecting a Sequencing Technology

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario 1: Incomplete genome assembly with short contigs.

- Potential Cause: The read length is insufficient to span long repetitive elements or large structural variants.

- Solution: If using ONT, optimize your wet-lab protocol for ultra-long reads. This includes using specialized HMW DNA extraction methods, wide-bore pipette tips to prevent shearing, and the ONT Ultra-Long DNA Sequencing Kit [26] [29]. Increasing sequencing coverage can also help, but longer reads are often the definitive solution.

Scenario 2: High error rates in the final assembly, especially in homopolymers.

- Potential Cause (ONT): This is a known systematic error for ONT. The basecalling model and flow cell version may not be optimized.

- Solution: Use the latest ONT chemistry (R10.4.1 flow cell) and the most accurate basecalling model (e.g., super-accuracy or SUP) [28]. For final polishing, apply a specialized error-correction tool like DeChat, which is designed for ONT R10 reads and preserves haplotypes while correcting errors [28].

- Alternative Approach: If high consensus accuracy is the priority from the start, consider using PacBio HiFi reads, which inherently provide high accuracy and do not suffer from homopolymer bias to the same extent [25] [23].

Scenario 3: Low sequencing yield or short read lengths.

- Potential Cause: Degraded or sheared input DNA.

- Solution: Rigorously check DNA quality. Use fluorometry (Qubit) for concentration and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Femto Pulse) for fragment size analysis [29] [30]. Ensure all sample handling steps are gentle to avoid physical shearing. For ONT, the Rapid Sequencing Kit is more tolerant of some DNA degradation but may not yield the longest reads [26].

Fundamental Concepts: Depth and Coverage

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between sequencing depth and coverage? These terms are often used interchangeably but describe distinct metrics crucial for your experimental design.

- Sequencing Depth (or Read Depth): This refers to the average number of times a specific nucleotide in the genome is read during the sequencing process. It is a measure of data redundancy and accuracy. For example, a depth of 30x means that each base position was sequenced, on average, 30 times [31] [32].

- Coverage: This describes the proportion of the entire genome or target region that has been sequenced at least once. It is a measure of comprehensiveness. Coverage is typically expressed as a percentage; for instance, 95% coverage means that 95% of the reference genome has been sequenced at least one time [31] [32].

Why are both depth and coverage critical for metagenomic assembly? Both metrics are interdependent and vital for generating high-quality, reliable data [31] [32].

- Sequencing Depth ensures confidence in base calling. A higher depth helps correct for sequencing errors, identify rare genetic variants within a population, and provides the data redundancy needed to resolve repetitive genomic regions during assembly [33] [32]. In cancer genomics or rare variant detection, depths of 500x to 1000x are often recommended [32].

- Sequencing Coverage ensures that the entirety of the target region is represented. In metagenomics, high coverage is necessary to capture sequences from low-abundance microbial taxa and to ensure that challenging genomic regions (e.g., those with high GC content) are not missed, which would lead to gaps in the assembled genomes [31] [33].

The relationship between these concepts can be visualized in the following workflow, which outlines the decision process for defining sequencing goals based on the research objectives and sample characteristics.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios and Solutions

FAQ: How do I select the appropriate sequencing depth for my project?

Selecting the correct depth is a multi-factorial decision. The following table summarizes recommended depths for various research applications [32]:

| Research Application | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Human Whole-Genome Sequencing | 30x - 50x | Balances cost with comprehensive coverage and accurate variant calling across the entire genome [32]. |

| Rare Variant / Cancer Genomics | 500x - 1000x | Enables detection of low-frequency mutations within a heterogeneous sample (e.g., tumors) [32]. |

| Transcriptome Analysis (RNA-seq) | 10 - 50 million reads | Provides sufficient sampling for accurate quantification of gene expression levels [32]. |

| Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) | Varies (Often >10x) | Dependent on community complexity. Higher depth aids in resolving genomes from low-abundance taxa and strains [34]. |

Common Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: Incomplete or Fragmented Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs)

- Potential Cause: Insufficient sequencing depth to cover low-abundance organisms or to resolve repetitive genomic regions [33] [34].

- Solution:

- Re-evaluate your required depth based on community complexity. For highly diverse communities, a deeper sequence is necessary to capture rare species [34].

- Use assembly quality assessment tools like CheckM or MetaQUAST to estimate completeness and contamination of your MAGs [35] [34]. If completeness is low, consider sequencing deeper.

- Consider using long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio HiFi) which can improve contiguity and completeness of assemblies, as demonstrated by tools like metaMDBG [36].

Problem 2: Failure to Detect Rare Variants or Low-Abundance Species

- Potential Cause: The sequencing depth is too low to statistically distinguish true rare variants from sequencing errors [33] [37].

- Solution:

- Significantly increase your sequencing depth. Studies aiming to characterize the full diversity of a library or environment require high-throughput sequencing to detect a larger number of unique sequences [37].

- Use statistical models to determine the depth required for detecting a variant at a given frequency with a specific confidence level.

- Ensure that the sequencing coverage is uniform; biases can cause some regions or genomes to be underrepresented even at high average depths [32].

Problem 3: High Assembly Error Rates and Misassemblies

- Potential Cause: Even with adequate depth, misassemblies can occur due to repetitive elements or strain variation. Standard metrics like N50 can be misleading without accuracy assessment [35].

- Solution:

- Employ reference-free misassembly prediction tools like ResMiCo to identify potentially misassembled contigs in your metagenome [35].

- Utilize multiple assemblers (e.g., SPAdes, metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT) and binning tools (e.g., MetaBAT) to optimize the reconstruction process, as their performance can vary based on the dataset [34].

- Optimize assembler hyperparameters for accuracy, not just for contiguity, using simulated datasets or tools like ResMiCo for guidance [35].

Experimental Protocols for Determining Optimal Depth

Protocol: A Framework for Depth and Coverage Optimization

This methodology outlines a process for empirically determining the optimal sequencing depth for a metagenomic study.

1. Define Study Objectives and Experimental Design [31] [32]

- Clearly state the primary goal: Are you detecting rare variants, assembling complete genomes, or profiling taxonomic abundance?

- Based on your goal, select a preliminary sequencing depth from the table in Section 2.

- Positive Control: If possible, include a mock microbial community with known genome sequences and abundances.

2. Conduct a Pilot Sequencing Study

- Sequence a subset of your samples at a very high depth. This creates a data reservoir from which you can computationally simulate lower sequencing depths.

3. Perform Wet-Lab and Computational Analysis

- DNA Extraction & Library Prep: Use high-quality, standardized protocols to minimize bias [32].

- Sequencing: Execute your plan on the appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina for short-read, PacBio HiFi or ONT for long-read).

- In-Silico Down-Sampling:

- Use tools like

seqtk(https://github.com/lh3/seqtk) to randomly sub-sample your high-depth sequencing reads to lower depths (e.g., 5x, 10x, 20x, 50x). - Assemble each down-sampled dataset independently using your chosen assembler (e.g., metaSPAdes, metaMDBG).

- Use tools like

4. Evaluate Assembly Quality and Saturation Metrics

- For each assembly depth, calculate the following metrics [35] [34]:

- Number of Contigs & N50: Measures contiguity.

- CheckM Completeness and Contamination: For binned MAGs.

- MetaQUAST Misassemblies: Reports relocation, inversion, and translocation errors [35].

- Number of High-Quality MAGs: The primary goal for many studies.

- Plot these metrics against sequencing depth.

5. Analyze Results and Determine Optimum

- Identify the point of "diminishing returns" where increasing depth no longer yields a significant improvement in the number of high-quality MAGs or a reduction in misassemblies [33]. This is your cost-effective optimal depth for the full study. The following diagram illustrates this analytical workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software and methodological tools essential for planning and analyzing sequencing depth in metagenomic studies.

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Depth/Coverage Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| CheckM | Software Tool | Assesses the completeness and contamination of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using lineage-specific marker genes, which is a key metric for evaluating sequencing sufficiency [35] [34]. |

| MetaQUAST | Software Tool | Evaluates the quality of metagenomic assemblies by comparing them to reference genomes, providing reports on misassemblies, and establishing a ground truth for simulated data [35]. |

| ResMiCo | Software Tool | A deep learning model for reference-free identification of misassembled contigs, crucial for evaluating assembly accuracy independent of reference databases [35]. |

| SPAdes / metaSPAdes | Assembler Software | A widely used genome assembler shown to be effective for metagenomic data, producing contigs of longer length and incorporating a high proportion of sequences [34]. |

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Sequencing Technology | Long reads with very high accuracy (≈99.9%) that significantly improve the quality and contiguity of metagenome assemblies, helping to resolve repetitive regions and produce circularized genomes [36]. |

| Mock Microbial Community | Wet-Lab Control | A defined mix of microorganisms with known abundances. Used as a positive control to validate sequencing depth, assembly, and binning protocols [36]. |

Algorithmic Approaches and Advanced Techniques for Complex Communities

De Bruijn Graph (DBG) and String Graph represent two fundamental paradigms for assembling sequencing reads into longer contiguous sequences (contigs). These methods are foundational for analyzing genomic and metagenomic data, each with distinct strengths and optimal use cases.

De Bruijn Graph (DBG) Assembly

- Core Principle: DBG assembly operates by breaking sequencing reads into shorter, fixed-length subsequences called k-mers [38] [39].

- Graph Construction: Each unique (k-1)-mer becomes a node in the graph. A directed edge connects two nodes if there exists a k-mer for which the first node is the prefix and the second node is the suffix [38] [9].

- Pathfinding: The assembly process is formulated as finding an Eulerian path—a path that traverses each edge exactly once—which corresponds to the reconstructed sequence [39].

- Primary Applications: Highly efficient for assembling large volumes of short-read data (e.g., from Illumina platforms) and is the default method for complex metagenomic samples [38] [9].

String Graph Assembly

- Core Principle: String graph assembly directly uses the overlaps between entire reads, without fragmenting them into k-mers [36].

- Graph Construction: Each read is a node in the graph. A directed edge represents a significant overlap between the suffix of one read and the prefix of another [9] [36].

- Pathfinding: Assembly involves finding a path through the overlap graph, and the resulting sequence is derived from the layout and consensus of the overlapping reads [9].

- Primary Applications: Particularly effective for assembling long-read sequences (e.g., PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore), even when they contain higher error rates [9] [36].

Comparison of Assembly Paradigms

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Optimal Use Cases

| Parameter | De Bruijn Graph (DBG) | String Graph |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Data | K-mers derived from reads [38] [39] | Full-length reads [9] [36] |

| Computational Efficiency | Highly efficient with high depth of coverage [9] | Efficiency degrades with increased read numbers [36] |

| Handling of Sequencing Errors | Sensitive to errors; requires pre-processing or error correction [9] [39] | Robust to higher error rates [9] |

| Handling of Repeats | Effective, but requires strategies for inexact repeats and k-mer multiplicity [39] | Effective using read pairing and long overlaps [9] |

| Typical Read Type | Short reads (e.g., Illumina) [38] [9] | Long reads (e.g., PacBio, Nanopore) [9] [36] |

| Scalability for Metagenomics | Excellent; default for short-read metagenomics [38] | Challenging for complex communities; improved by minimizers [36] |

| Example Tools | SPAdes, MEGAHIT, SOAPdenovo [38] [9] | hifiasm-meta, metaFlye [36] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Assembly Challenges

| Challenge | DBG-Based Approach | String Graph-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Low Abundance Organisms | Gene-targeted assembly (e.g., Xander) weights paths in the graph [38] | Less effective; relies on sufficient coverage for overlap detection [36] |

| Strain Heterogeneity | Colored DBGs or abundance-based filtering (e.g., metaMDBG) [38] [36] | Can struggle with complex strain diversity without specific filtering [36] |

| High Memory Usage | Use succinct DBGs (sDBG) or compacted DBGs (cDBG) [38] | Use of minimizers (e.g., metaMDBG) to reduce graph complexity [36] |

| Fragmented Assemblies | Use paired-end information to scaffold and resolve repeats [39] | Use long reads and mate-pair data to span repetitive regions [9] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: De Bruijn Graph Assembly for Metagenomes

This protocol outlines the key steps for assembling metagenomic short-read data using a DBG-based tool like MEGAHIT or SPAdes [38].

- Read Pre-processing and Error Correction: Quality trim reads and correct sequencing errors using tools like BayesHammer (within SPAdes) or Rcorrector. This is critical as errors create false k-mers and bulges in the graph [39].

- K-mer Selection and Graph Construction:

- Graph Simplification:

- Contig Generation: Traverse the simplified graph to output linear contiguous sequences (contigs) [38].

- Scaffolding: Use paired-end read information to order, orient, and link contigs, estimating gap sizes between them to form longer scaffolds [39].

Protocol 2: String Graph Assembly for Long Reads

This protocol describes the process for assembling long-read metagenomic data (e.g., PacBio HiFi) using a string graph-based tool like hifiasm-meta or a hybrid approach like metaMDBG [36].

- Overlap Detection: Perform an all-versus-all comparison of reads to find significant pairwise overlaps. Tools use minimizers to efficiently compute these overlaps without full alignments [36].

- String Graph Construction: Build a graph where each node is a read. A directed edge is created from read A to read B if the suffix of A overlaps with the prefix of B [9] [36].

- Graph Simplification: Remove transitive edges (redundant overlaps that are implied by other overlaps) to simplify the graph topology [9].

- Unitig Generation: Extract non-branching paths from the graph, which form the initial assembled sequences.

- Consensus Generation: For each path in the graph, perform a multiple sequence alignment of all reads supporting that path to generate a high-quality consensus sequence [9].

- Strain De-duplication: Identify and remove nearly identical sequences that likely represent strain-level variation to reduce redundancy [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Their Functions

| Tool / Resource | Function in Assembly | Relevant Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| SPAdes [38] [9] | De novo genome and metagenome assembler designed for short reads. | De Bruijn Graph |

| MEGAHIT [38] | Efficient and scalable de novo assembler for large and complex metagenomes. | De Bruijn Graph |

| hifiasm-meta [36] | Metagenome assembler designed for PacBio HiFi reads using an overlap graph. | String Graph |

| metaFlye [36] | Assembler for long, noisy reads that uses a repeat graph, an adaptation of string graphs. | String Graph / Hybrid |

| metaMDBG [36] | Metagenome assembler for HiFi reads that uses a minimizer-space DBG, a hybrid approach. | Hybrid |

| CheckM [36] | Tool for assessing the quality and contamination of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). | Quality Control |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a De Bruijn graph assembler over a String graph assembler for my metagenomic project? Choose a De Bruijn graph assembler (e.g., MEGAHIT, SPAdes) when your data consists of short reads from platforms like Illumina. DBGs are computationally efficient for high-coverage datasets and are the standard for complex metagenomic communities [38] [9]. Opt for a String graph assembler (e.g., hifiasm-meta) when working with long reads from PacBio HiFi or Oxford Nanopore technologies, as they can natively handle the longer overlaps and are more robust to higher error rates in raw long reads [9] [36].

Q2: How does k-mer size selection impact De Bruijn graph assembly, and what is the best strategy for choosing 'k'? K-mer size is a critical parameter. A smaller k increases connectivity in the graph, which is beneficial for low-coverage regions, but makes the assembly more sensitive to sequencing errors and less able to resolve repeats. A larger k helps distinguish true overlaps from random matches and resolves shorter repeats, but can break the graph into more contigs in low-coverage regions [39]. The best strategy is to use a multi-k approach, as implemented in tools like MEGAHIT and metaMDBG, which iteratively assembles data using increasing k-mer sizes to balance connectivity and specificity [38] [36].

Q3: What are the primary reasons for highly fragmented metagenome assemblies, and how can I improve contiguity? Fragmentation arises from: a) Low sequencing coverage of specific taxa, preventing the assembly of complete paths. b) Strain heterogeneity, which creates complex, unresolvable branches in the graph. c) Intra- and inter-genomic repeats that collapse or break the assembly graph [36]. To improve contiguity:

- Increase sequencing depth to cover rarer community members.

- For DBG assemblies, use paired-end information for scaffolding [39].

- For complex strain issues, use tools with abundance-based filtering like metaMDBG [36].

- Utilize long-read technologies to span repetitive regions [36].

Q4: My assembly tool is running out of memory. What optimizations or alternative tools can I use? High memory usage is common with large metagenomes. Consider:

- Switching to a memory-efficient assembler: For short reads, MEGAHIT is highly optimized. For long reads, metaMDBG uses a minimizer-space DBG to drastically reduce memory [36].

- Using a compacted graph representation: Tools like MegaGTA and MetaGraph use succinct DBGs (sDBGs) or compacted DBGs (cDBG) to reduce memory footprint [38].

- Pre-filtering reads: For gene-centric analyses, use gene-targeted assembly (e.g., Xander) which only assembles specific genes, reducing the data volume [38].

Q5: What are hybrid approaches like metaMDBG, and when are they advantageous? Hybrid approaches like metaMDBG combine concepts from different paradigms. MetaMDBG, for instance, constructs a de Bruijn graph in minimizer space (using sequences of minimizers instead of k-mers) and incorporates iterative assembly and abundance-based filtering [36]. This is advantageous for assembling long, accurate reads (HiFi) from metagenomes because it retains the scalability of DBGs while being better suited to handle the variable coverage depths and strain complexity found in microbial communities, leading to more complete genomes [36].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My assembly results are fragmented. How can I improve contiguity?

Fragmentation can often be addressed by adjusting parameters related to repetitive regions and coverage. For hifiasm-meta, increasing the -D or -N values may improve resolution of repetitive regions but requires longer computation time. Alternatively, adjusting --purge-max can make primary assemblies more contiguous, though setting this value too high may collapse repeats or segmental duplications [40]. For metaMDBG, the multi-k assembly approach with iterative graph simplification inherently addresses variable coverage depths that cause fragmentation [36]. Before parameter tuning, verify your HiFi data quality is sufficient, as low-quality reads are a common cause of fragmentation [40].

Q2: How do I handle unusually large assembly sizes that exceed estimated genome size?

This issue commonly occurs when the assembler misidentifies the homozygous coverage threshold. In hifiasm-meta, check the log for the "homozygous read coverage threshold" value. If this is significantly lower than your actual homozygous coverage peak, use the --hom-cov parameter to manually set the correct value. Note that when tuning this parameter, you may need to delete existing *hic.bin files to force recalculation, though versions after v0.15.5 typically handle this automatically [40]. For all assemblers, also verify that your estimated genome size is accurate, as an incorrect estimate can misleadingly suggest a problem [40].

Q3: What is the minimum read coverage required for reliable assembly? For hifiasm-meta, typically ≥13x HiFi reads per haplotype is recommended, with higher coverage generally improving contiguity [40]. metaMDBG demonstrates good performance even at lower coverages, successfully circularizing 92% of genomes with coverage >50x in benchmark studies, compared to 59-65% for other assemblers [36]. myloasm specifically maintains better genome recovery than other tools at low coverages, making it suitable for samples with limited sequencing depth [41].

Q4: How can I reduce misassemblies in complex metagenomic samples?

To minimize misassemblies in hifiasm-meta, set smaller values for --purge-max, -s (default: 0.55), and -O, or use the -u option [40]. For myloasm, the polymorphic k-mer approach with strict handling of mismatched SNPs across SNPmers naturally reduces misjoining of similar sequences [41]. metaMDBG's abundance-based filtering strategy effectively removes complex errors and inter-genomic repeats that lead to misassemblies [36]. For all tools, closely related strains with >99% ANI may still be challenging to separate completely.

Q5: What are the key differences in how these assemblers handle strain diversity?

- myloasm: Uses polymorphic k-mers (SNPmers) to resolve similar sequences, allowing matching of polymorphic SNPmers while being strict for mismatched SNPs, enabling separation of strains as low as 98% similar [41].

- metaMDBG: Employs a progressive abundance filter that incrementally removes unitigs with coverage ≤50% of seed coverage, effectively simplifying strain complexity [36].

- hifiasm-meta: Uses coverage information to prune unitig overlaps and joins unitigs from different haplotypes, though strains with very high similarity (>99%) may still be collapsed [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Assembly Quality Issues

| Symptom | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low completeness scores | Insufficient coverage, incorrect read selection | For hifiasm-meta: Disable read selection with -S if applied inappropriately [43]. Verify coverage meets minimum requirements [40]. |

| High contamination in MAGs | Incorrect binning, unresolved strain diversity | Use metaMDBG' abundance-based filtering [36] or myloasm's polymorphic k-mer approach for better strain separation [41]. |

| Unbalanced haplotype assembly | Misidentified homozygous coverage | Set --hom-cov parameter manually in hifiasm-meta to match actual homozygous coverage peak [40]. |

| Many misjoined contigs | High similarity between strains | For hifiasm-meta, reduce -s value (default 0.55) and use -u option [40]. For myloasm, leverage its random path model for better resolution [41]. |

Performance and Computational Issues

| Symptom | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely long runtime | Large dataset, complex community, suboptimal parameters | For hifiasm-meta: Use -S for high-redundancy datasets to enable read selection [43]. For metaMDBG, the minimizer-space approach inherently improves efficiency [36]. |

| High memory usage | Graph complexity, large k-mer sets | metaMDBG uses minimizer-space De Bruijn graphs with significantly reduced memory requirements compared to traditional approaches [36]. |

| Assembly stuck or crashed | Low-quality HiFi reads, contaminants | Check k-mer plot for unusual patterns indicating insufficient coverage or contaminants [40]. Verify read accuracy meets tool requirements. |

Parameter Optimization Guidelines

| Parameter | Assembler | Effect | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| --hom-cov | hifiasm-meta | Sets homozygous coverage threshold | Critical when auto-detection fails; set to observed homozygous coverage peak [40]. |

| -s | hifiasm-meta | Similarity threshold for overlap (default: 0.55) | Reduce for more divergent samples; increase cautiously for more sensitive overlap detection [40]. |

| -S | hifiasm-meta | Enables read selection | Use for high-redundancy datasets to reduce coverage of highly abundant strains [43]. |

| --n-weight, --n-perturb | hifiasm-meta | Affects Hi-C phasing resolution | Increase to improve phasing results at computational cost [40]. |

| Temperature parameter | myloasm | Controls strictness of graph simplification | Iterate from high to low values for progressive cleaning [41]. |

| Abundance threshold | metaMDBG | Filters unitigs by coverage | Progressive filtering from 1% to 50% of seed coverage effectively removes strain variants [36]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Metagenome Assembly Protocol

Metagenomic Assembly Workflow

Benchmarking and Validation Protocol

For comparing assembler performance, follow this established benchmarking approach used in recent studies [36]:

Dataset Selection: Include both mock communities (e.g., ATCC MSA-1003, ZymoBIOMICS D6331) and real metagenomes (e.g., human gut, anaerobic digester sludge) [36].

Quality Metrics:

- For mock communities: Calculate average nucleotide identity (ANI) against reference genomes

- For real communities: Use CheckM for completeness/contamination assessment

- Record number of circularized contigs and high-quality MAGs

Performance Tracking:

- Computational resources (memory, time)

- Contiguity statistics (N50, number of contigs >1 Mb)

- Strain resolution capability

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes benchmark results from recent studies comparing the three assemblers:

| Metric | hifiasm-meta | metaMDBG | myloasm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular MAGs (human gut) | 62 [36] | 75 [36] | Not reported |

| Strain resolution | Moderate | High | Very High (98% ANI) [41] |

| Memory efficiency | Moderate | High | Varies by dataset |

| E. coli strain circularization | 1 of 5 strains [42] | 1 of 5 strains [36] | Not specifically tested |

| Low-coverage performance | Requires ≥13x [40] | Good down to 50x [36] | Excellent at low coverage [41] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Mock community for quality control | Use with each project to monitor extraction and assembly performance [44]. |

| PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 | HiFi library preparation | Optimized for 8M SMRT cells, enables high-quality metagenome assembly [44]. |

| HiFi Read Data | Input for all assemblers | Require mean read length >10kb and quality >Q20 for optimal results [44]. |

| CheckM/CheckM2 | MAG quality assessment | Essential for evaluating completeness and contamination of assembled genomes [44]. |

| MetaBAT 2 & SemiBin2 | Binning algorithms | Use complementary binning approaches followed by DAS-Tool consolidation [44]. |

| GTDB database | Taxonomy annotation | Use latest release (e.g., R07-RS207) for accurate classification of novel organisms [44]. |

Core Concepts & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between individual assembly and co-assembly? Individual assembly processes sequencing reads from each metagenomic sample separately. In contrast, co-assembly combines reads from multiple related samples (e.g., from a longitudinal study or the same environment) before the assembly process [45] [46]. While individual assembly minimizes the mixing of data from different microbial strains, co-assembly can recover genes from low-abundance organisms that would otherwise have insufficient coverage to be assembled from a single sample [46].

Q2: Why is co-assembly particularly powerful for low-biomass samples? Low-biomass samples, by definition, yield very limited DNA, often below the detection limit of conventional quantification methods [47]. This results in lower sequencing coverage for many community members. Co-assembly pools data, effectively increasing the cumulative coverage for less abundant microorganisms and making their genomes accessible for assembly and analysis, which is a key strategy for improving gene detection in these challenging environments [46].

Q3: What are the main trade-offs of using a co-assembly approach? Co-assembly offers significant benefits but comes with specific challenges that must be considered [45]:

| Pros of Co-assembly | Cons of Co-assembly |

|---|---|

| More data for assembly, leading to longer contigs [46] | Higher computational overhead (memory and time) [45] [13] |

| Access to genes from lower-abundance organisms [46] | Risk of increased assembly fragmentation due to strain variation [45] [46] |

| Can reduce the assembly of redundant sequences across samples [13] | Higher risk of misclassifying metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) due to mixed populations [45] |

Q4: Are there alternative strategies that combine the benefits of individual and co-assembly? Yes, two advanced strategies have been developed:

- Mix-Assembly: This approach involves performing both individual assembly on each sample and a separate co-assembly on all pooled reads. The resulting genes from both strategies are then clustered together to create a final, non-redundant gene catalogue. This has been shown to produce a more extensive and complete gene set than either method alone [46].

- Sequential Co-assembly: This method reduces computational resources and redundant sequence assembly by successively applying assembly and read-mapping tools. It has been demonstrated to use less memory, be faster, and produce fewer assembly errors than traditional one-step co-assembly [13].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Problems and Solutions in Co-assembly Workflows

Problem 1: Highly Fragmented Assembly Output Your co-assembly results in many short contigs instead of long, contiguous sequences.

| Possible Cause | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Strain Heterogeneity | The samples pooled for co-assembly contain numerous closely related strains. | Consider the mix-assembly strategy [46]. Alternatively, use assemblers with presets designed for complex metagenomes (e.g., MEGAHIT's --presets meta-large) [46]. |

| Inappropriate Sample Selection | Co-assembling samples from vastly different environments or ecosystems. | Co-assembly is most reasonable for related samples, such as longitudinal sampling of the same site [45]. Re-evaluate sample grouping based on experimental design. |

| Overly Stringent K-mers | Using only a narrow range of k-mer sizes during the De Bruijn graph construction. | Use an assembler that employs multiple k-mer sizes automatically (e.g., metaSPAdes) or specify a broader, sensitive k-mer range. |

Problem 2: Inefficient Resource Usage or Assembly Failure The co-assembly process demands excessive memory or fails to complete.

| Possible Cause | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely Large Dataset | The combined read set from all samples is too large for available RAM. | Implement sequential co-assembly to reduce memory footprint [13]. Alternatively, perform read normalization on the combined reads before assembly to reduce data volume [46]. |

| Default Software Settings | The assembler is using parameters optimized for a single genome or a simple community. | Switch to parameters designed for large, complex metagenomes (e.g., in MEGAHIT, use --presets meta-large) [46]. |

Problem 3: Contamination or Chimeras in Amplified Low-Biomass Samples When Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) is used prior to co-assembly, non-specific amplification products can contaminate the dataset.

| Possible Cause | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Bias & Artifacts | MDA can introduce chimeras and artifacts, especially with very low DNA input [47]. | Use modified MDA protocols like emulsion MDA or primase MDA to reduce nonspecific amplification [47]. For critical applications, treat MDA as a last resort and use direct metagenomics whenever DNA quantity allows [47]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology for a Mix-Assembly Strategy

This protocol, adapted from a Baltic Sea metagenome study, combines the strengths of individual and co-assembly to generate comprehensive gene catalogues [46].

Read Preprocessing:

- Tool: Cutadapt [46].

- Action: Remove low-quality bases and sequencing adapters from all raw sequencing reads.

- Typical Parameters:

-q 15, 15 -n 3 --minimum-length 31.

Individual Sample Assembly:

Read Normalization for Co-assembly:

- Tool: BBNorm (from BBmap package) [46].

- Action: Normalize the combined set of reads from all samples to reduce data complexity and volume.

- Typical Parameters:

target=70 mindepth=2.

Co-assembly:

- Tool: MEGAHIT [46].

- Action: Assemble the entire normalized read set.

- Typical Parameters:

--presets meta-large(recommended for large, complex metagenomes).

Gene Prediction:

- Tool: Prodigal (v.2.6.3 or higher) [46].

- Action: Identify and extract protein-coding genes from all assembled contigs (from both individual and co-assembly).

- Parameters:

-p meta.

Protein Clustering to Create Non-Redundant Gene Catalogue:

- Tool: MMseqs2 [46].

- Action: Cluster all predicted protein sequences from individual and co-assemblies to create a final, non-redundant gene set.

- Parameters:

-c 0.95 --min-seq-id 0.95 --cov-mode 1 -cluster-mode 2. This clusters proteins at ≥95% amino acid identity.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the mix-assembly protocol:

Workflow for Sequential Co-assembly to Conserve Resources

For computationally intensive projects, this sequential method can be more efficient [13].

- Initial Assembly: Assemble the first sample or a small batch of samples.

- Read Mapping: Map reads from subsequent samples to the initial assembly.

- Recovery of Unmapped Reads: Collect all reads that did not map to the initial assembly.

- Iterative Assembly: Assemble the pool of unmapped reads.

- Final Combination: Combine the initial assembly with the new assembly from unmapped reads to form a comprehensive co-assembly.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Assembly

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) Kits | Amplifies whole genomes from low-biomass samples to generate sufficient DNA for sequencing [47]. | Introduces coverage bias against high-GC genomes and can cause chimera formation. Essential for DNA concentrations below 100 pg [47]. |

| Emulsion MDA | A modified MDA protocol that partitions reactions into water-in-oil droplets to reduce amplification artifacts and improve uniformity [47]. | Reduces nonspecific amplification compared to bulk MDA, leading to more representative metagenomic libraries from low-input DNA [47]. |

| Primase MDA | Uses a primase enzyme for initial primer generation, reducing nonspecific amplification from contaminating DNA [47]. | Shows amplification bias in community profiles, especially for low-input DNA. Performance varies by sample type [47]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., PowerSoil) | Isolates microbial genomic DNA from complex environmental samples, including filters and soils. | Includes bead-beating for rigorous cell lysis. Critical for unbiased representation of community members [47]. |

| Normalization Tools (e.g., BBNorm) | Computational "reagent" that reduces data redundancy and volume by normalizing read coverage, making large co-assemblies feasible [46]. | Applied before co-assembly to lower computational overhead. Parameters like target=70 help manage dataset size [46]. |

Summary Table of Assembly Strategies and Outcomes

The choice of assembly strategy directly impacts the quality and completeness of your results, as demonstrated by comparative studies [46].

| Metric | Individual Assembly | Co-assembly | Mix-Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Catalogue Size | Large but highly redundant | Limited by strain heterogeneity | Most extensive and non-redundant [46] |

| Gene Completeness | High for abundant genomes | Fragmented for mixed strains | More complete genes [46] |

| Detection of Low-Abundance Genes | Poor | Good | Excellent [46] |

| Computational Demand | Moderate per sample, low per run | Very High | Highest (runs both strategies) [46] |

| Strain Resolution | High | Low | Medium |

| Best for | Abundant genome recovery, strain analysis | Recovering rare genes from related samples | Creating comprehensive reference catalogues [46] |

Utilizing Polymorphic K-mers and Abundance Information to Resolve Strain Diversity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are polymorphic k-mers and how do they help in resolving strain diversity? Polymorphic k-mers are all of the subsequences of length k that comprise a DNA sequence. Comparing the frequency of these k-mers across samples yields valuable information about sequence composition and similarity without the computational cost of pairwise sequence alignment or phylogenetic reconstruction. This makes them particularly useful for quantifying microbial diversity (alpha diversity) and similarity between samples (beta diversity) in complex metagenomic samples, serving as a proxy for phylogenetically aware diversity metrics, especially when reliable phylogenies are not available [48].