Niche-Specific Virulence: Comparative Genomics and Evolutionary Drivers of Pathogen Adaptation

This article synthesizes recent advances in understanding how virulence factors are shaped by ecological niches.

Niche-Specific Virulence: Comparative Genomics and Evolutionary Drivers of Pathogen Adaptation

Abstract

This article synthesizes recent advances in understanding how virulence factors are shaped by ecological niches. For researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational concept that many 'virulence factors' are, in fact, niche adaptation factors selected by environmental pressures. We detail methodological approaches in comparative genomics and machine learning for identifying these traits, address challenges in distinguishing true virulence, and present validation through cross-niche comparisons. The synthesis underscores that a One Health perspective, integrating human, animal, and environmental reservoirs, is crucial for managing antibiotic resistance and developing targeted antimicrobial strategies.

Defining Virulence in Context: From Niche Factors to Pathogenic Traits

The traditional concept of "virulence factors" is undergoing a significant paradigm shift in microbial pathogenesis research. Historically, any bacterial structure or strategy that contributed to the infectious potential of a pathogen was classified as a virulence factor. This included capsules, flagella, pili, secretion systems, exotoxins, and iron acquisition systems [1]. However, the increasing interest in the human microbiota and comparative genomics has revealed a critical insight: harmless commensal organisms frequently possess the very same structures and strategies to compete in complex biological ecosystems [1]. This observation challenges the fundamental definition of virulence factors and suggests that many such factors might be more accurately described as "niche factors" – essential adaptations for survival in specific environments, whether pathogenic or commensal.

This distinction is not merely semantic but has profound implications for how we understand host-microbe interactions, develop therapeutic interventions, and regulate probiotic products [1]. The emerging framework necessitates a more precise vocabulary that distinguishes between factors causing damage to the host and those that simply enable microorganisms to persist in their ecological niche. This article examines the conceptual shift from virulence factors to niche factors through the lens of comparative genomics and experimental studies, providing objective data and methodologies that illuminate this evolving paradigm.

Conceptual Framework: Distinguishing Niche Adaptation from Pathogenesis

Defining Characteristics and Functions

The distinction between virulence factors and niche factors hinges on their fundamental purpose and distribution across microbial species.

Table 1: Comparative Features of Virulence Factors and Niche Factors

| Feature | Virulence Factors | Niche Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Cause damage to host; access sterile body sites | Promote colonization, survival, and competition in a specific ecological niche |

| Presence in Commensals | Rare or absent in harmless commensals | Common in both pathogens and commensals occupying similar niches |

| Host Damage | Directly cause tissue damage or dysregulate immunity | Do not inherently cause damage; may become detrimental in compromised hosts or abnormal locations |

| Examples | Cytolytic toxins, invasins, superantigens, neurotoxins | Bile tolerance systems, attachment mechanisms, nutrient acquisition systems, immune evasion in non-sterile sites |

| Regulatory Implications | Prohibit use in probiotics | Generally acceptable for probiotics unless context indicates risk |

This conceptual framework finds practical application in regulatory science. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidelines require evidence that "virulence factors" are absent in novel commensals proposed for use as probiotics [1]. A literal interpretation could mistakenly prohibit the use of beneficial microbes like Bifidobacterium breve due to the presence of TadIV pili, which function as niche factors in the gastrointestinal tract despite being classified as virulence factors in pathogens like Yersinia enterocolitica [1].

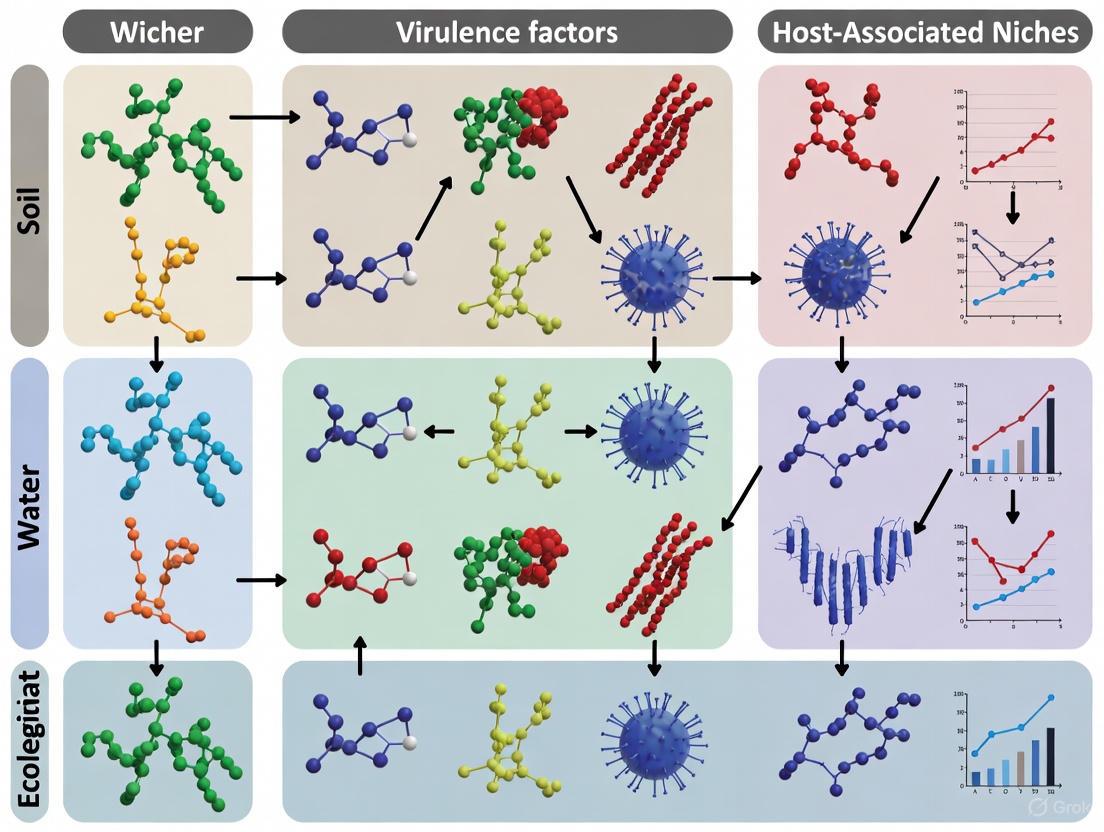

Visualizing the Conceptual Relationship

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between virulence factors, niche factors, and their shared characteristics in pathogenic and commensal microorganisms.

Genomic Evidence: Comparative Analyses Across Ecological Niches

Recent advances in whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics have enabled large-scale comparative studies that illuminate the genetic basis of niche adaptation [2]. These investigations reveal how similar genetic tools are deployed by both pathogens and commensals, supporting the niche factor concept.

Large-Scale Genomic Comparisons

A comprehensive comparative genomic analysis of 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes isolated from various hosts and environments demonstrated significant variability in bacterial adaptive strategies [2] [3]. Human-associated bacteria, particularly from the phylum Pseudomonadota, exhibited higher detection rates of carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) genes and adhesion-related factors, indicating co-evolution with the human host [2]. In contrast, environmental isolates showed greater enrichment in genes related to metabolism and transcriptional regulation, highlighting their adaptability to diverse external environments [2].

Table 2: Genomic Feature Distribution Across Ecological Niches (Based on 4,366 Bacterial Genomes)

| Genomic Feature | Human-Associated | Animal-Associated | Environment | Clinical Isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes | Higher detection rates | Moderate detection rates | Variable | Elevated in human pathogens |

| Adhesion Factors | Enriched | Present | Less common | Highly enriched |

| Antibiotic Resistance Genes | Variable | Significant reservoirs | Less common | Highest detection rates |

| Metabolic Pathway Genes | Host-adapted | Host-adapted | Highly diverse | Constrained |

| Immune Evasion Factors | Enriched | Present | Rare | Highly enriched |

These findings align with the niche factor hypothesis, demonstrating that many genes traditionally classified as virulence factors are actually niche-specific adaptations. For instance, bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity, initially characterized as a virulence factor in Listeria monocytogenes, is also present in many commensals marketed as probiotics [1]. This widespread distribution suggests BSH primarily functions as a gastrointestinal niche factor rather than a dedicated virulence mechanism.

Within-Host Evolution Studies

Investigations of bacterial evolution within host environments provide compelling evidence for the niche factor concept. A detailed study tracking the evolution of a single multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clone across 110 patients during a 5-year nosocomial outbreak revealed strong positive selection targeting key virulence factors [4]. The research demonstrated convergent evolutionary trajectories dominated by reduced acute virulence and recurrent changes in iron uptake regulation, capsule production, and lipopolysaccharide composition – changes that likely represent clinical niche adaptations [4].

Notably, mutations in genes associated with capsule production (wcoZ, wzc), lipopolysaccharide synthesis (manB, manC), and iron utilization (sufB, sufC, fepA/fes) showed significant signs of positive selection, with a nonsynonymous vs. synonymous substitution ratio (dN/dS) of 49.7 for genes with three or more independent mutations [4]. These adaptive changes often resulted in trade-offs during gastrointestinal colonization, highlighting how niche-specific optimizations can simultaneously enhance fitness in one context while reducing it in another.

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Differentiation

Comparative Genomic Workflow

The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow for conducting comparative genomic analyses to identify niche-specific adaptations across bacterial isolates from different ecological sources.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

Genome Collection and Quality Control: Obtain high-quality bacterial genomes from public databases (e.g., gcPathogen) [2]. Implement stringent quality control: exclude sequences assembled at contig level; retain genomes with N50 ≥50,000 bp; ensure CheckM completeness ≥95% and contamination <5%; remove genomes with unclear source information [2].

Ecological Niche Annotation: Categorize genomes based on detailed metadata of isolation sources: "human" (clinical samples, human tissues), "animal" (livestock, wildlife), and "environment" (soil, water, air) [2]. This classification enables analysis of adaptation to different ecological contexts.

Functional Annotation: Predict open reading frames using Prokka v1.14.6 [2]. Annotate functions using:

- COG database for general functional categories (RPS-BLAST, e-value <0.01, coverage >70%)

- dbCAN2 for carbohydrate-active enzymes (HMMER, e-value <1e-5)

- VFDB for virulence factor identification (ABRicate with default parameters)

- CARD for antibiotic resistance genes [2]

Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees using 31 universal single-copy genes identified by AMPHORA2 [2]. Perform multiple sequence alignment with Muscle v5.1 and tree construction with FastTree v2.1.11 [2].

Statistical Comparison: Convert phylogenetic trees to evolutionary distance matrices using R package ape [2]. Perform k-medoids clustering to identify population structure. Calculate enrichment of specific functions across ecological niches using hypergeometric tests with multiple testing correction.

Machine Learning Application: Employ algorithms (e.g., random forests, support vector machines) to identify signature genes associated with specific niches [2]. Use Scoary for gene presence/absence association testing [2].

Phenotypic Validation Assays

Genomic predictions require phenotypic validation to confirm the functional role of putative niche factors:

Mucoviscosity and Capsule Production: Quantify capsule expression using India ink staining and sedimentation assays [4].

Serum Survival: Assess serum resistance by incubating bacteria in fresh human serum and monitoring viability over time [4].

Iron Utilization: Evaluate siderophore production using chrome azurol S assays and measure growth under iron-limited conditions [4].

Biofilm Formation: Quantify biofilm production using crystal violet staining in microtiter plates [4].

Infection Potential: Assess virulence alterations using Galleria mellonella infection models, monitoring survival curves and bacterial loads [4].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Virulence/Niche Factor Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Databases | VFDB, CARD, PATRIC, COG, dbCAN | Virulence factor, resistance gene, and functional annotation | Comparative genomics, VFAR analyses |

| Genomic Analysis Tools | Prokka, ABRicate, Scoary, AMPHORA2 | Genome annotation, gene presence/absence testing, phylogenetic marker identification | Functional annotation, association studies |

| Alignment & Phylogenetics | Muscle v5.1, FastTree v2.1.11, MEGA v11.0.13 | Multiple sequence alignment, phylogenetic tree construction | Evolutionary analysis, molecular phenetics |

| Metabolomic Pathways | MetaboAnalyst 6.0, KEGG, HMDB | Metabolic pathway enrichment analysis | Metabolomic adaptations across niches |

| Phenotypic Assay Reagents | Chrome azurol S, India ink, Crystal violet | Siderophore detection, capsule staining, biofilm quantification | Functional validation of niche adaptations |

Case Studies: Exemplifying the Conceptual Shift

Bacterial Systems: FromListeriato Probiotics

The bile tolerance system BilE in Listeria monocytogenes was initially characterized as a virulence factor because it contributes to gastrointestinal survival and is regulated by the master virulence regulator PrfA [1]. However, similar bile tolerance mechanisms must exist in commensal organisms inhabiting the bile-rich regions of the GI tract [1]. This realization prompted reconsideration of BilE as a niche factor required for gastrointestinal survival, which happens to play an important role in the infectious lifestyle of the pathogen [1].

Similarly, bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity in L. monocytogenes was described as a PrfA-regulated virulence factor [1]. However, deletion of bsh genes reduces the ability of the organism to colonize by diminishing bile coping capacity, and BSH activity is also present in many commensals marketed as probiotics [1]. This distribution across pathogens and commensals strongly supports its reclassification as a niche factor.

Fungal Systems:Cryptococcus neoformansAdaptations

Molecular phenetic and metabolomic analyses of Cryptococcus neoformans isolates reveal distinct adaptive strategies between clinical and environmental niches [5]. Clinical isolates demonstrate enriched sulfur metabolism and glutathione pathways, likely representing adaptations to oxidative stress in host environments [5]. In contrast, environmental isolates favor methane and glyoxylate pathways, suggesting adaptations for survival in carbon-rich environments [5].

These niche-specific metabolic specializations illustrate how the same microorganism utilizes different biochemical pathways to thrive in distinct ecological contexts. The clinical adaptations enhance virulence in human hosts but originated as niche-specific optimization rather than dedicated virulence mechanisms.

Emerging Frontiers: Virulence Factor Activity Relationships (VFARs)

The concept of Virulence Factor Activity Relationships (VFARs) represents a predictive framework for ranking microbial risks based on structural and functional characteristics of virulence factors [6]. Similar to quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs) for chemicals, VFARs leverage bioinformatics databases and tools to compare newly identified virulence factors against known references for virulence prediction [6].

More than 20 bioinformatics databases and tools have been developed over the last decade with dedicated virulence and antimicrobial resistance prediction capabilities [6]. Key resources include:

- PATRIC: Integration and visualization of virulence factors across 22,000 whole genome sequences [6]

- VFDB: Distribution of virulence factors in distinct categories with inter-genera comparison capability [6]

- CARD: Curated collection of antibiotic resistance gene sequences with detection software [6]

- VirulenceFinder: Detection of virulence genes based on whole-genome sequencing data [6]

These tools enable researchers to apply VFAR approaches to rank and prioritize organisms important to specific niches, combining genomic data with engineering and economic analyses for comprehensive risk assessment [6].

The conceptual shift from virulence factors to niche factors represents a fundamental evolution in our understanding of host-microbe interactions. This refined perspective acknowledges that many microbial factors traditionally viewed through a lens of pathogenicity actually represent adaptations to specific ecological niches, exploited by both commensals and pathogens alike.

This paradigm shift has profound implications for drug development and probiotic regulation. Therapeutic strategies can now more precisely target genuine virulence mechanisms (those causing direct host damage) while preserving niche factors that enable beneficial colonization. Furthermore, regulatory frameworks for probiotics can evolve to distinguish between true virulence factors and essential niche factors required for gastrointestinal survival and competition.

As comparative genomics and functional studies continue to illuminate the continuum between commensalism and pathogenesis, the niche factor concept provides a more nuanced and accurate framework for understanding microbial ecology and evolution. This perspective ultimately enhances our ability to develop targeted antimicrobials, design effective probiotics, and implement rational regulatory policies that reflect the complex reality of host-microbe interactions.

The evolutionary arms race between bacterial pathogens and their hosts is a fundamental aspect of microbial pathogenesis. Understanding how ecological niches shape bacterial evolution is critical for developing novel therapeutic strategies, especially in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance. This comparison guide examines how distinct selective pressures in human, animal, and environmental reservoirs drive the diversification of virulence factors and resistance mechanisms in bacterial pathogens. The dynamic interplay between these niches facilitates continuous pathogen evolution, with significant implications for global health.

Recent advances in comparative genomics have revealed that bacterial pathogens employ niche-specific adaptive strategies to colonize new hosts and survive under diverse environmental conditions [2]. The World Health Organization's One Health approach emphasizes the interconnected nature of human, animal, and environmental health, particularly relevant when considering the dissemination of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes [2]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of virulence mechanisms across ecological niches, offering experimental data and methodological frameworks to support research in bacterial pathogenesis and drug development.

Genomic Adaptations Across Ecological Niches

Comparative Genomic Analysis of Niche-Specific Adaptations

Large-scale comparative genomic studies reveal distinct evolutionary trajectories for bacteria occupying different ecological niches. An analysis of 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes isolated from various hosts and environments demonstrated significant variability in bacterial adaptive strategies [2].

Table 1: Genomic Features Across Ecological Niches

| Ecological Niche | Dominant Bacterial Phyla | Enriched Genomic Features | Adaptive Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-associated | Pseudomonadota | Higher prevalence of carbohydrate-active enzyme genes; virulence factors for immune modulation and adhesion | Gene acquisition; co-evolution with human host |

| Animal-associated | Diverse phyla | Significant reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes; host-specific virulence factors | Horizontal gene transfer; zoonotic transmission |

| Environmental | Bacillota, Actinomycetota | Metabolism and transcriptional regulation genes; stress response systems | Genome reduction; metabolic versatility |

| Clinical settings | Multiple pathogenic genera | High abundance of antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., fluoroquinolone resistance) | Rapid evolution under antibiotic pressure |

Human-associated bacteria, particularly from the phylum Pseudomonadota, exhibit genomic signatures of co-evolution with their host, including higher detection rates of carbohydrate-active enzyme genes and virulence factors related to immune modulation and adhesion [2]. In contrast, environmental bacteria show greater enrichment in genes related to metabolism and transcriptional regulation, highlighting their adaptability to diverse physical and nutritional conditions. Clinical isolates demonstrate the highest prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes, reflecting the strong selective pressure imposed by antimicrobial therapy.

Within-Host Evolutionary Trajectories in Opportunistic Pathogens

Hospital outbreaks provide unique opportunities to study bacterial evolution over defined timeframes. A detailed analysis of a multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clone during a 5-year nosocomial outbreak affecting 110 patients revealed strong positive selection targeting key virulence factors [4].

Table 2: Convergent Evolutionary Changes in a Hospital K. pneumoniae Outbreak

| Gene/Region | Function | Type of Change | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| manB/manC | O-antigen synthesis (O3b-type) | Nonsynonymous mutations | Altered lipopolysaccharide structure |

| wcoZ/wzc | Capsule biosynthesis (KL51) | Nonsynonymous mutations | Modified capsule production |

| uvrY | Response regulator in BarA-UvrY two-component system | Nonsynonymous mutations | Altered regulation of virulence and metabolism |

| sufB/sufC | Iron-sulfur cluster synthesis | Nonsynonymous mutations | Changes in iron homeostasis |

| fepA/fes intergenic region | Siderophore uptake and enterobactin esterase regulation | Regulatory mutations | Modified iron acquisition |

The study identified a strong signal of positive selection (dN/dS = 49.7) in genes with three or more independent mutations, indicating adaptive within-host evolution [4]. Convergent evolutionary trajectories were dominated by reduced acute virulence and recurrent changes in iron uptake regulation, capsule, and lipopolysaccharide production, with enhanced biofilm formation. These phenotypic changes represent clinical niche adaptations, with some resulting in trade-offs during gastrointestinal colonization.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Niche Adaptation

Methodologies for Comparative Genomic Analysis

The experimental framework for comparing virulence factors across ecological niches relies on integrated genomic and phenotypic approaches:

Genome Sequencing and Quality Control: Researchers obtained metadata for 1,166,418 human pathogens from the gcPathogen database and implemented stringent quality control procedures [2]. This included retaining genome sequences with N50 ≥50,000 bp, CheckM completeness ≥95%, and contamination <5%. Following removal of bacterial genomes with unclear source information, 4,366 high-quality, non-redundant pathogen genome sequences were retained for comparative analysis.

Phylogenetic Analysis: To construct robust phylogenetic trees, 31 universal single-copy genes were retrieved from each genome using AMPHORA2 [2]. For each marker gene, multiple sequence alignments were generated using Muscle v5.1, followed by concatenation of the 31 alignments into a comprehensive dataset. Maximum likelihood trees were constructed using FastTree v2.1.11, with k-medoids clustering (k=8) implemented to compare genomic differences among bacteria from different ecological niches within the same ancestral clade.

Functional Annotation: Open reading frames were predicted using Prokka v1.14.6, with functional categorization performed through RPS-BLAST mapping to the Cluster of Orthologous Groups database (e-value threshold 0.01, minimum coverage 70%) [2]. Carbohydrate-active enzyme genes were annotated using dbCAN2 to map ORFs to the CAZy database, with filtering based on hmm_eval 1e-5.

Virulence Factor and Antibiotic Resistance Analysis: Virulence factors were identified using the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB), while antibiotic resistance genes were annotated through the CARD database [2] [7]. These comprehensive annotations enabled systematic comparison of virulence and resistance mechanisms across ecological niches.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comparative genomic analysis of bacterial niche adaptation

Assessing Virulence Gene Expression Under Environmental Stress

Understanding how environmental stressors affect virulence expression provides crucial insights into niche-specific adaptations. A study on Bacillus cereus employed quantitative PCR to measure expression of four virulence genes (nheA, hblD, cytK, and entFM) under different stress conditions [8].

Growth Conditions and Stress Exposure: B. cereus was cultured in LB broth medium for 14 h with shaking (37°C, 160 rpm), with OD values measured every 2 hours to plot growth curves [8]. For stress experiments, bacteria were exposed to different temperatures (20°C, 30°C, 40°C), pH levels (4.0, 6.0, 8.0), and salt concentrations (0.5%, 1.5%, 3.0%), both as single factors and in combination.

RNA Extraction and qPCR Analysis: After 14 hours of incubation under stress conditions, RNA was extracted using the RNAprep pure Bacteria Kit [8]. Quantitative PCR was performed using the StepOnePlus Real-Time Fluorescence PCR System with TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus). Primer sequences for virulence genes were designed based on established references, with amplification conditions optimized for each target.

Pathogenicity Assessment: The pathological damage caused by B. cereus exposed to different stress conditions was evaluated in mouse models using histological sections of various organs [8]. This integrated approach connected gene expression changes with actual virulence potential.

The results demonstrated that environmental stressors significantly modulate virulence gene expression. High temperature (40°C) inhibited expression of most virulence genes, while pH and salt concentration had variable effects depending on the specific gene [8]. Under multiple stressors, nheA, hblD and cytK showed lowest expression at 40°C, pH 6.0, and 3.0% salt, while entFM was minimally expressed at 20°C, pH 8.0, and 1.5% salt concentration.

Pathogen-Specific Adaptation Mechanisms

Niche-Specific Virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumoniae exemplifies how pathogens differentially utilize virulence factors across host niches. Research on hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) has demonstrated that virulence plasmid-encoded factors play distinct roles depending on the infection site [9].

The virulence plasmid (KpVP) in hvKp encodes aerobactin (iuc), salmochelin (iro), and the capsule regulator rmpA [9]. Systematic analysis using isogenic mutants in various murine infection models revealed that aerobactin is indispensable for stable gut colonization, primarily by overcoming iron competition from the microbiota. In contrast, salmochelin plays a pivotal role in bloodstream dissemination by evading host-derived lipocalin-2. The hypermucoviscous capsule regulated by rmpA enhances systemic dissemination but is dispensable for gut colonization.

Figure 2: Niche-specific functions of K. pneumoniae virulence factors

This niche-specific functionality illustrates the sophisticated adaptation of pathogens to different host environments. The co-inheritance of iro and iuc loci in hypervirulent strains suggests their combined presence confers a selective advantage across host niches [9]. Furthermore, the convergence of multidrug resistance and hypervirulence in emerging strains highlights the evolutionary plasticity of K. pneumoniae in response to medical interventions.

Virulence and Resistance Dynamics in Escherichia coli from Dairy Cattle

Dairy cattle represent important reservoirs of Escherichia coli strains carrying both virulence and resistance factors, with significant implications for public health. A comprehensive genomic analysis of 172 E. coli isolates from dairy cattle across seven countries revealed distinct patterns of gene distribution [10].

Table 3: Virulence and Resistance Genes in Dairy Cattle E. coli

| Gene Category | Specific Genes | ESBL E. coli (%) | Non-ESBL E. coli (%) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Resistance | sul2, blaTEM-1B, tet(A) | 92.1, 85.7, 81.0 | 62.4, 58.7, 64.2 | Sulfonamide, β-lactam, and tetracycline resistance |

| Virulence Factors | astA, iss, lpfA | 68.3, 61.9, 41.3 | 45.9, 33.9, 27.5 | Enteroaggregative toxin, increased serum survival, long polar fimbriae |

| Mobile Genetic Elements | IncFIB, IncFII, IncQ1 | 93.7, 84.1, 68.3 | 78.9, 69.7, 52.3 | Plasmid replicons facilitating horizontal gene transfer |

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli isolates showed significantly higher prevalence of both antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors compared to non-ESBL isolates [10]. The study identified a strong correlation (p < 0.001) between the presence of plasmid replicons (IncFIB, IncFII) and the co-occurrence of resistance and virulence genes, highlighting the role of mobile genetic elements in the dissemination of these traits.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that ESBL E. coli isolates from cattle were predominantly classified within phylogroups A and B1, with sequence types ST10, ST101, and ST69 being most common [10]. The genetic diversity of E. coli in dairy environments, coupled with the extensive horizontal gene transfer mediated by plasmids, integrons, and insertion sequences, creates a complex ecological landscape where virulence and resistance traits freely circulate between commensal and pathogenic strains.

Research Reagent Solutions for Virulence Studies

The following research reagents represent essential tools for investigating virulence factors and niche-specific adaptations in bacterial pathogens:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Bacterial Virulence

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| VFDB Database | Virulence Factor Database (http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/) | Comprehensive virulence factor annotation | Curated information on VFs from medically significant pathogens; integrated anti-virulence compound data [11] [7] |

| dbCAN2 | HMMER-based annotation tool | Carbohydrate-active enzyme identification | Mapping to CAZy database with hmm_eval 1e-5 filtering parameter [2] |

| CARD Database | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database | Antibiotic resistance gene annotation | Detection of resistance mechanisms across antibiotic classes [2] |

| AMPHORA2 | Marker gene-based phylogenetic tool | Phylogenetic tree construction | Identifies 31 universal single-copy genes for robust phylogeny [2] |

| RNAprep pure Bacteria Kit | Takara Bio | Bacterial RNA extraction | High-quality RNA for virulence gene expression studies [8] |

| TB Green Premix Ex Taq II | Takara Bio | Quantitative PCR | SYBR Green-based detection of virulence gene expression [8] |

The VFDB deserves special emphasis as it has recently been enhanced to include information on anti-virulence compounds, providing valuable resources for drug design and repurposing [11]. The database currently contains 902 individual anti-virulence compounds across 17 superclasses, with detailed information on their chemical structures, molecular targets, and mechanisms of action. This integration of virulence factor data with therapeutic compound information bridges the gap between chemists and microbiologists, supporting the development of novel anti-virulence strategies.

The comparative analysis of virulence factors across human, animal, and environmental niches reveals fundamental principles of bacterial evolution and adaptation. Human-associated pathogens demonstrate specialized adaptations for immune evasion and host interaction, while environmental isolates maintain metabolic versatility for diverse conditions. Animal reservoirs serve as crucial interfaces where virulence and resistance traits exchange between commensal and pathogenic bacteria.

The methodological framework presented here, integrating comparative genomics, phenotypic characterization, and environmental stress studies, provides a robust foundation for investigating niche-specific adaptations. As bacterial pathogens continue to evolve in response to antimicrobial pressure and changing ecological conditions, understanding these dynamic evolutionary relationships remains critical for developing effective interventions against infectious diseases.

Future research directions should focus on the convergence of hypervirulence and multidrug resistance, particularly the mechanisms by which pathogens maintain both traits without fitness trade-offs. Additionally, exploring how virulence regulation responds to niche-specific signals will yield insights into bacterial decision-making processes during infection. The developing field of anti-virulence therapy, targeting specific virulence factors without affecting bacterial growth, represents a promising alternative to conventional antibiotics that may exert less selective pressure for resistance development [11].

Bacterial pathogens demonstrate a remarkable capacity to thrive in diverse ecological niches, from environmental reservoirs to human hosts. This adaptability is driven by dynamic genomic evolution, where gene acquisition, gene loss, and genome reduction serve as fundamental mechanisms enabling bacterial survival and specialization. Understanding these processes is crucial for elucidating pathogenic potential, predicting emerging threats, and developing novel antimicrobial strategies [3] [2]. These genomic alterations facilitate the fine-tuning of bacterial physiology to specific host environments, allowing pathogens to circumvent immune defenses, access novel nutrient sources, and establish persistent infections [12].

The study of these adaptive strategies has been revolutionized by comparative genomics, which enables researchers to systematically analyze genetic differences across thousands of bacterial isolates from diverse sources. Recent large-scale studies examining 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes have revealed that different bacterial phyla exhibit distinct preferential strategies for host adaptation [3] [2]. For instance, while Pseudomonadota frequently utilize gene acquisition, Actinomycetota and Bacillota often employ genome reduction as their primary adaptive mechanism [2]. This review provides a comparative analysis of these three fundamental genomic strategies, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to virulence factor research across ecological niches.

Comparative Analysis of Genomic Adaptation Strategies

Table 1: Characteristics of Primary Genomic Adaptation Strategies

| Adaptation Strategy | Primary Mechanism | Impact on Genome Size | Representative Genera/Phyla | Key Virulence Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Acquisition | Horizontal gene transfer of virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes, and pathogenicity islands | Increase or maintenance | Pseudomonadota, Escherichia, Staphylococcus | Acquisition of toxin genes, adhesion factors, immune evasion proteins [3] [2] |

| Gene Loss | Loss of non-essential genes through deletion mutations | Decrease | Burkholderia, Mycoplasma | Streamlined metabolism, loss of environmental persistence capabilities [12] [2] |

| Genome Reduction | Extensive gene loss and pseudogene accumulation through reductive evolution | Significant decrease | Actinomycetota, Bacillota, obligatory intracellular pathogens | Enhanced host dependence, specialized virulence factor retention [13] [2] |

Table 2: Niche-Specific Distribution of Virulence and Resistance Genes

| Ecological Niche | Prevalent Adaptive Strategy | Virulence Factor Enrichment | Antibiotic Resistance Gene Prevalence | Notable Genomic Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Clinical | Gene acquisition | Immune modulation and adhesion factors [2] | High, particularly fluoroquinolone resistance [3] [2] | Specialized secretion systems, toxin genes |

| Animal Host | Mixed strategies (acquisition and loss) | Adhesion and colonization factors | Significant reservoir of resistance genes [3] [2] | Host-specific adaptation genes |

| Environmental | Gene loss/genome reduction | Metabolic and transcriptional regulation genes [2] | Lower compared to clinical isolates [3] | Stress response genes, environmental sensing systems |

Gene Acquisition: Expanding Pathogenic Potential

Gene acquisition through horizontal gene transfer represents a fundamental strategy for rapid bacterial adaptation to new niches. This process enables bacteria to incorporate novel genetic material, including virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes, and metabolic pathway components, from distantly related organisms [3] [2].

Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence

Horizontal gene transfer occurs primarily through three mechanisms: conjugation (direct cell-to-cell transfer), transformation (uptake of environmental DNA), and transduction (viral-mediated transfer). Comparative genomic studies have revealed that human-associated bacteria, particularly from the phylum Pseudomonadota, exhibit higher detection rates of carbohydrate-active enzyme genes and virulence factors related to immune modulation and adhesion, indicating co-evolution with the human host through gene acquisition [2].

Staphylococcus aureus provides a compelling example of this adaptive strategy, having acquired a variety of host-specific genes through horizontal transfer. These include immune evasion factors in equine hosts, methicillin resistance determinants in human-associated strains, heavy metal resistance genes in porcine hosts, and lactose metabolism genes in strains adapted to dairy cattle [2]. This acquisition of niche-specific genes enables rapid adaptation to selective pressures, including antibiotic exposure and host immune defenses.

Experimental identification of acquired genes typically involves comparative genomic analysis using tools such as BLAST-based orthology detection and phylogenetic reconstruction to identify genes with discordant evolutionary histories relative to the core genome. The Scoary algorithm, combined with machine learning approaches, can identify niche-associated genes with high predictive accuracy [2].

Gene Loss and Genome Reduction: Strategic Simplification

While gene acquisition expands genomic repertoire, strategic gene loss and genome reduction represent alternative adaptation strategies that optimize bacterial fitness by eliminating unnecessary genetic material [13] [2].

Adaptive Stasis in Genome-Reduced Bacteria

Freshwater genome-reduced bacteria (≤2.1 Mbp) exhibit extended periods of adaptive stasis, characterized by significantly higher levels of sequence conservation and invariance in their secreted proteomes compared to their larger-genomed counterparts [13]. This contrasts with the dominant paradigm of continuous evolution through niche adaptation and reflects a different evolutionary strategy where conservation of essential functions takes precedence over genetic innovation.

In these genome-reduced bacteria, secreted proteomes show a combination of low functional redundancy and high selection pressure, resulting in significantly higher levels of conservation [13]. This pattern suggests that even mutations that do not impact amino acid identity may incur a fitness cost, possibly by altering optimal gene expression levels crucial for survival in their specific niche.

Case Studies in Pathogenic Adaptation

Burkholderia mallei illustrates how genome reduction facilitates the transition from environmental saprophyte to obligate pathogen. Evolving from B. pseudomallei, B. mallei underwent substantial genome reduction through insertion sequence-mediated deletions, losing genes necessary for survival in soil environments while retaining virulence factors essential for mammalian pathogenesis [12]. This reductive evolution resulted in increased host dependence but enhanced pathogenic specialization.

Similarly, Mycoplasma genitalium has undergone extensive genome reduction, including the loss of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism, enabling the bacterium to reallocate limited resources toward maintaining a mutualistic relationship with its host [2]. This strategic gene loss reflects adaptive optimization to a specific host niche.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Genomic Adaptation

Comparative Genomic Workflow

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Comparative Genomic Analysis

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Genome Collection and Quality Control

Researchers conducting comparative genomic analysis begin with stringent quality control procedures. As demonstrated in recent large-scale studies, this involves:

- Genome Sourcing: Obtaining metadata for bacterial pathogens from comprehensive databases such as gcPathogen, which contains information on over 1 million human pathogens [3] [2].

- Quality Filtering: Retaining only high-quality genome sequences with N50 ≥50,000 bp, completeness ≥95%, and contamination <5% as evaluated by CheckM [3] [2].

- Niche Annotation: Categorizing genomes based on detailed isolation source metadata into human, animal, or environmental niches [2].

- Redundancy Reduction: Calculating genomic distances using Mash and performing Markov clustering to remove highly similar genomes (distance ≤0.01) [2].

Functional and Virulence Annotation

Comprehensive functional annotation enables researchers to identify adaptive genes across different niches:

- Open Reading Frame Prediction: Using Prokka v1.14.6 for rapid prokaryotic genome annotation [3] [2].

- Functional Categorization: Mapping predicted ORFs to the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST with e-value threshold of 0.01 and minimum coverage of 70% [3] [2].

- Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme Annotation: Applying dbCAN2 to map ORFs to the CAZy database using HMMER with parameter hmm_eval 1e-5 [3] [2].

- Virulence Factor Identification: Utilizing ABRicate v1.0.1 to map bacterial genomes to the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) for systematic identification of virulence genes [3].

Identification of Adaptive Genes

Advanced computational methods enable the detection of niche-specific adaptive genes:

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Constructing maximum likelihood trees from 31 universal single-copy genes using FastTree v2.1.11 after alignment with Muscle v5.1 [2].

- Population Clustering: Performing k-medoids clustering using the pam function from the R cluster package to identify evolutionarily coherent groups [2].

- Association Testing: Applying the Scoary algorithm to identify genes significantly associated with specific ecological niches while accounting for population structure [2].

- Machine Learning Validation: Using machine learning approaches (e.g., random forests) to validate the predictive power of identified adaptive genes for niche classification [2].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Genomic Adaptation Studies

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Adaptation Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| VFDB (Virulence Factor Database) | Database | Curated repository of bacterial virulence factors | Systematic identification of virulence factors across bacterial genomes [7] |

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) | Database | Antibiotic resistance gene reference | Detection and annotation of resistance genes in genomic data [3] [2] |

| COG (Cluster of Orthologous Groups) | Database | Phylogenetic classification of proteins encoded in complete genomes | Functional categorization of gene products [3] [2] |

| CAZy (Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes) | Database | Specialist database for enzymes that build and break down complex carbohydrates | Identification of carbohydrate metabolism adaptation [3] [2] |

| Prokka | Software Tool | Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation | Automated annotation of genomic features in bacterial genomes [3] [2] |

| Scoary | Algorithm | Pan-genome-wide association study tool | Identification of genes associated with specific niches or phenotypes [2] |

| CheckM | Software Tool | Assess genome quality and completeness | Quality control of genomic datasets prior to comparative analysis [2] |

Implications for Virulence Factor Research and Therapeutic Development

Understanding genomic adaptation strategies provides crucial insights for antimicrobial development and infectious disease management. The distinct distribution of virulence factors across ecological niches highlights potential targets for anti-virulence therapies [7]. For instance, targeting niche-specific adhesion factors or immune evasion proteins could disrupt host colonization without exerting the strong selective pressure associated with conventional antibiotics [14] [7].

The identification of animal hosts as significant reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes underscores the importance of the One Health approach to infectious disease control, which integrates human, animal, and environmental health [3] [2]. Furthermore, the discovery of human host-specific signature genes, such as hypB, which may regulate metabolism and immune adaptation in human-associated bacteria, reveals potential targets for novel therapeutic interventions [2].

Recent advances in CRISPR-based therapeutics also offer promising avenues for directly targeting bacterial virulence factors or reversing antibiotic resistance [15]. As our understanding of genomic adaptation mechanisms deepens, so too does our capacity to develop precisely targeted antimicrobial strategies that disrupt pathogenic specialization while minimizing collateral damage to commensal microbiota.

The concept of protozoan predation serving as a "training ground" for bacterial virulence is grounded in the coincidental evolution hypothesis, which proposes that virulence factors arose as a response to environmental selective pressures, such as predation, rather than for virulence per se [16] [17]. For opportunistic pathogens that transit in the environment between hosts, interactions with bacterivorous protists are a major evolutionary driver. The defense mechanisms bacteria develop to resist protozoan predation are often functionally identical to the traits required to survive within human phagocytic immune cells, such as macrophages [17]. This review provides a comparative analysis of how predation pressure shapes bacterial virulence across different ecological niches and bacterial species, synthesizing key experimental data to guide future research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Anti-Predator Virulence Mechanisms

Bacteria have evolved a diverse arsenal of mechanisms to resist protozoan predation, many of which have been co-opted for pathogenesis in human hosts. The table below summarizes key virulence factors, their roles in anti-predator defense, and their impact on human virulence.

Table 1: Dual Role of Bacterial Anti-Predator Mechanisms and Virulence Factors

| System/Mechanism | Bacterium | Role in Anti-Predation | Role in Human Virulence | Key Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type III Secretion System (T3SS) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Kills Acanthamoeba castellanii [16] | Causes pneumonia [16] | Acanthamoeba castellanii, mouse lung infection |

| Legionella pneumophila | Enables intracellular parasitism of amoeba [16] | Causes legionellosis [16] | Acanthamoeba spp., human monocytes | |

| Escherichia coli | Promotes survival inside A. castellanii [16] | Causes diarrheal disease [16] | A. castellanii co-culture | |

| Type VI Secretion System (T6SS) | Vibrio cholerae | Cytotoxic against Dictyostelium discoideum [16] | Causes cholera & gastroenteritis [16] | D. discoideum plaque assay |

| Violacein Pigment | Chromobacterium violaceum | Induces rapid protist cell death [16] | Opportunistic pathogen [16] | Co-culture with various protists |

| Shiga Toxin | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Kills Tetrahymena thermophila [16] [18] | Causes hemorrhagic colitis [16] | T. thermophila predation assay |

| Biofilm Formation | P. aeruginosa, V. cholerae | Physical barrier against ingestion; promoted by predator cues [16] [17] | Chronic lung infections, antibiotic resistance [16] [19] | Flow cells, confocal microscopy, wax moth larvae |

| Intracellular Survival | L. pneumophila, V. cholerae | Prevents phagosome-lysosome fusion; resists digestion [16] [17] | Survival within human macrophages [17] | Acanthamoeba & Dictyostelium co-culture |

The experimental evidence reveals a fundamental distinction between the strategies of intracellular and extracellular pathogens. Intracellular pathogens like Legionella pneumophila rely on active invasion and sophisticated intracellular maneuvers, such as blocking phagosome-lysosome fusion, to survive and replicate within the protist [16] [17]. In contrast, extracellular pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa often utilize toxin secretion and biofilm formation to avoid internalization altogether [17]. This ecological specialization has direct implications for their pathogenicity in humans.

Key Experimental Models and Data

Experimental Evolution: Protist Predation and Virulence Attenuation

Direct experimental tests have been crucial in validating the link between predation and virulence evolution. A key study investigated how the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila and PNM phage, both individually and in combination, shape the evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 virulence, measured as mortality in wax moth larvae [18].

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Evolution and Virulence Outcomes

| Selection Pressure | Evolved Bacterial Phenotype | Impact on Virulence (in Wax Moth Larvae) | Associated Pleiotropic Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protist Predation Alone | Selected for small, inedible colony variants; increased biofilm formation [18] | Attenuated virulence [18] | Reduced growth rate in absence of enemies [18] |

| Phage Parasitism Alone | No significant phenotypic change observed [18] | No significant change in virulence [18] | Not detected |

| Protist & Phage Combined | Phage constrained antipredator defense (biofilm formation) [18] | Constrained protist-driven virulence attenuation [18] | Reduced growth cost associated with anti-protist defense [18] |

This study demonstrates that protist selection can be a strong coincidental driver of attenuated bacterial virulence, and that phages can constrain this effect due to their impact on population dynamics and conflicting selection pressures [18]. The pleiotropic link between reduced growth and lower virulence suggests a fitness trade-off that can be exploited therapeutically.

Ecological Drivers of Protozoa-Resisting Bacteria (PRB)

The selection for PRB in natural environments is influenced by nutrient availability and predation pressure. An enrichment-dilution experiment using natural lake water revealed how these factors favor different PRB with distinct ecological strategies [20].

Table 3: Ecological Drivers of Protozoa-Resisting Bacteria (PRB) in Aquatic Systems

| PRB Genus | Response to High Predation-Pressure | Response to Nutrient Enrichment/Disturbance | Ecological Strategy / Niche |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterium | Strong positive effect (e.g., >13-fold increase with 50% higher predation) [20] | Negative association with enrichment [20] | Specialist in high-predation, stable environments |

| Pseudomonas | Weak, less important effect [20] | Strong positive effect; dominates community (30-50% of reads) [20] | Generalist in disturbed, nutrient-rich environments |

| Rickettsia | Apparent positive effect (co-occurred with predators) [20] | Effect not statistically significant [20] | Specialist, likely dependent on host association |

The findings indicate that PRB with different ecological strategies can be expected in waters of varying nutrient levels. Pseudomonas thrives in enriched, disturbed systems, whereas Mycobacterium is favored under high, stable predation pressure [20]. This ecological understanding helps predict the environmental conditions that may lead to the enrichment of potential pathogens.

Methodologies: Core Experimental Protocols

To facilitate replication and further research, here are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this field.

Protocol 1: Experimental Evolution with Dual Enemies

This protocol is adapted from the study investigating the concurrent impact of protist and phage selection on P. aeruginosa evolution [18].

- Bacterial Strain: Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (ATCC 15692).

- Enemies: Tetrahymena thermophila (protist predator) and PNM phage (bacterial virus, Podoviridae family).

- Culture Conditions: 6 ml of 1% King's Medium B (diluted KB) in 25 ml glass vials.

- Experimental Design:

- Set up a full factorial design with four treatments: Bacterium alone (control), Bacterium + Phage, Bacterium + Protist, Bacterium + Protist + Phage.

- Replicate each treatment (e.g., n=5 microcosms).

- Inoculate all microcosms with ~10^5 cells of PAO1.

- Add enemies according to treatment: ~3.6x10^3 phage particles and/or ~250 protist cells.

- Selection Regime:

- Incubate microcosms at 28°C without shaking.

- Every 4 days, vortex microcosms and transfer 1 μL of culture to 6 ml of fresh medium. This serial passage is repeated for a total of 5 transfers (24 days).

- At each transfer, monitor bacterial density (by spectrophotometry and plating), phage density (by plaque assay), and protist density (by direct microscopy).

- Post-Selection Analysis:

- After the final transfer, isolate bacterial clones from predators and phages by plating on KB agar.

- Measure evolved phenotypes: defense against protists and phages, biofilm formation, growth rate in enemy-free medium, and virulence in an animal model (e.g., wax moth larvae).

Protocol 2: Assessing Virulence in Wax Moth Larvae

This in vivo model provides a rapid and ethical method to quantify bacterial virulence [18].

- Host Organism: Last instar larvae of the Greater Wax Moth (Galleria mellonella).

- Infection Procedure:

- Grow ancestral and evolved bacterial isolates to mid-log phase.

- Wash and resuspend bacteria in a saline solution (e.g., PBS) to a standardized concentration (e.g., 10^5 - 10^6 CFU/mL).

- Inject a defined volume (e.g., 10 μL) of the bacterial suspension into the larval hemocoel via a proleg using a microsyringe.

- Include a control group injected with saline only.

- Virulence Measurement:

- Incubate injected larvae at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C) and monitor survival every 12-24 hours for up to 5 days.

- Virulence is quantified as the proportion of dead larvae over time, and results can be analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and statistical tests like the log-rank test.

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Bacterial Anti-Predator Signaling and Virulence Pathways

Diagram 1: Bacterial anti-predator signaling and virulence pathways. Protozoan predation selects for and induces multiple bacterial defense systems, which function coincidentally as virulence factors during human infection. Key regulatory systems like Quorum Sensing (QS) coordinate the expression of these traits.

Experimental Evolution Workflow with Dual Enemies

Diagram 2: Experimental evolution workflow with dual enemies. P. aeruginosa is evolved under different selection regimes (predation, parasitism, both, or none). After serial passaging, evolved clones are isolated and analyzed for a suite of phenotypic traits, including virulence in an animal model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents and Models for Studying Predation-Driven Virulence

| Reagent / Model System | Category | Function in Research | Specific Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthamoeba castellanii | Protist Model | Mimics macrophage phagocytosis; selective force for intracellular pathogens [16] [17] | Co-culture with L. pneumophila to study phagosome maturation blocking [16] |

| Dictyostelium discoideum | Protist Model | Genetic model for phagocytosis; identifies virulence factors conserved in metazoans [16] [17] | Plaque assay with V. cholerae to identify T6SS mutants [16] |

| Tetrahymena thermophila | Protist Model | Bacterivorous ciliate for experimental evolution and studying toxin resistance [18] [20] | Predation assay to demonstrate Shiga toxin's anti-protozoal function [18] |

| PNM Phage & similar | Viral Parasite | Adds multi-enemy selection pressure; constrains evolution of anti-protist traits [18] | Experimental evolution of P. aeruginosa to study trade-offs in multi-enemy environments [18] |

| Galleria mellonella | Animal Model | High-throughput, ethical in vivo model for quantifying bacterial virulence [18] | Measuring larval survival after injection with evolved P. aeruginosa clones [18] |

| Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM) | Analytical Tool | Statistical modeling to quantify effects of environmental variables on PRB abundance [20] | Determining the impact of predation-pressure vs. nutrients on Mycobacterium and Pseudomonas [20] |

Implications for Drug Development and Future Research

The understanding that virulence is often a by-product of environmental adaptation has profound implications for anti-virulence drug development [19]. Targeting virulence factors that are primarily maintained by environmental pressures, rather than host infection, may result in lower selective pressure for resistance in the clinical setting [19]. Furthermore, the pleiotropic costs associated with anti-predator defenses, such as reduced growth rates, suggest that disarming these virulence factors could push pathogens back toward a less fit state [18]. Future research should focus on quantifying the strength of selection imposed by diverse protozoan communities in natural reservoirs and further elucidate the genetic and metabolic trade-offs that link anti-predator defense to virulence. This ecological-evolutionary perspective will be crucial for predicting and mitigating the emergence of new opportunistic pathogens.

Tools for Discovery: Genomic and Computational Methods for Profiling Virulence

Comparative Genomics Frameworks for Large-Scale Pathogen Analysis

Comparative genomics has become an indispensable methodology for unraveling the genetic basis of pathogen virulence, host adaptation, and ecological niche specialization. By analyzing genomic variations across diverse bacterial populations, researchers can identify key virulence factors (VFs) and antibiotic resistance genes that enable pathogens to colonize specific hosts and environments [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for investigating the distribution of virulence factors across different ecological niches—a research area with significant implications for understanding disease pathogenesis, predicting emerging threats, and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

The integration of large-scale genomic datasets with advanced bioinformatics tools has enabled unprecedented insights into the evolutionary mechanisms driving pathogen diversification. Studies of bacterial pathogens isolated from human, animal, and environmental sources have revealed niche-specific genomic signatures and adaptive strategies, highlighting the complex interplay between pathogen genetics and host environment [3] [2]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of current comparative genomics frameworks, their methodological approaches, and applications in virulence factor research, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for selecting appropriate methodologies for large-scale pathogen analysis.

Key Frameworks and Databases for Virulence Factor Analysis

Core Databases for Virulence Factor Annotation

Table 1: Major Databases for Virulence Factor Analysis in Comparative Genomic Studies

| Database Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Data Scope | Applications in Comparative Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFDB (Virulence Factor Database) | VF identification and annotation | Curated collection of experimentally verified VFs; integrated anti-virulence compound data | 3581 verified VFGs; 62,332 non-redundant orthologues and alleles [11] [21] | Reference-based VF annotation; pathobiont VF profiling; cross-niche VF distribution analysis |

| VFDB 2.0 (Expanded) | VF orthologue and allele identification | Includes ssANI-based orthologues/alleles; mobile VF annotation; host taxonomy | 62,332 VFG sequences across 135 species [21] | High-resolution VF tracking; mobile genetic element-associated VF identification |

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) | Antibiotic resistance gene annotation | Curated resistance determinants and resistance mechanisms | Not specified in search results | Co-occurrence analysis of VFs and AMR genes; resistance gene transfer studies |

| COG (Cluster of Orthologous Groups) | Functional categorization | Protein classification based on phylogenetic relationships | Not specified in search results | Functional enrichment analysis across niches; core genome analysis |

| dbCAN2 | Carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation | HMM-based CAZy annotation; enzyme class prediction | Not specified in search results | Nutrient acquisition strategy comparison; host adaptation analysis |

Analytical Frameworks and Toolkits

Table 2: Computational Frameworks for Large-Scale Pathogen Genomics

| Framework/Tool | Methodological Approach | Key Advantages | Performance Metrics | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetaVF Toolkit | VF profiling based on VFDB 2.0; TSI filtering | Species-level VFG identification; mobile VF prediction; bacterial host attribution | TDR >97%; FDR <4.000767e-05% at 90% TSI [21] | Metagenomic VF profiling; pathobiont carrier identification; cross-niche VF comparison |

| PLMVF | Protein language model (ESM-2) with ensemble learning; structural similarity integration | Remote homology detection; 3D structural feature incorporation; TM-score prediction | 86.1% accuracy; outperforms sequence-only methods [22] | Novel VF prediction; functional annotation of hypothetical proteins |

| Traditional Comparative Genomics Pipeline | Phylogenetic analysis; COG/CAZy annotation; VFDB/CARD mapping | Established methodology; comprehensive functional profiling; phylogenetic context | Varies with dataset size and parameters [3] [2] | Niche-specific gene identification; evolutionary studies; broad-scale adaptation analysis |

| Scoary with Machine Learning | Gene presence/absence association; machine learning classification | Identification of niche-associated genes; predictive model building | 0.63 average silhouette coefficient at k=8 clusters [3] | Host-specific gene identification; predictive model development |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Niche Virulence Factor Analysis

Protocol 1: Large-Scale Comparative Genomic Analysis Across Ecological Niches

Objective: To identify niche-specific virulence factors and adaptive mechanisms across human, animal, and environmental pathogens.

Methodology Details:

Genome Dataset Curation

- Source 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes with comprehensive metadata from databases such as gcPathogen [3] [2]

- Implement stringent quality control: completeness ≥95%, contamination <5%, N50 ≥50,000 bp

- Annotate ecological niches (human, animal, environment) based on isolation source and host information

- Remove redundant genomes using Mash distances (≤0.01) and Markov clustering

Phylogenetic Framework Construction

Functional and Virulence Annotation

- Predict open reading frames with Prokka v1.14.6

- Annotate functional categories using COG database (RPS-BLAST, e-value 0.01, 70% coverage)

- Identify carbohydrate-active enzymes with dbCAN2 (HMMER, hmm_eval 1e-5)

- Annotate virulence factors using VFDB and antibiotic resistance genes using CARD via ABRicate v1.0.1 [3]

Statistical Analysis and Machine Learning

- Perform enrichment analysis for functional categories across niches

- Identify niche-associated genes using Scoary

- Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest) to build predictive models for niche specificity [3]

Protocol 2: Metagenomic Virulence Factor Profiling with MetaVF

Objective: To profile virulence factor genes in metagenomic data with species-level resolution and mobile genetic element association.

Methodology Details:

Data Preprocessing and Alignment

- Process clean metagenomic reads or metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs)

- For short reads: map against expanded VFDB 2.0 alignment dataset

- For long HiFi reads or MAGs: perform nucleotide BLAST against pathogenic alignment dataset [21]

Stringent Filtering with Tested Sequence Identity (TSI)

- Apply TSI threshold (90%) determined using artificial metagenomic datasets

- Filter VF-mapped reads to achieve true discovery rate >97% and false discovery rate <4.000767e-05% [21]

- Select best BLAST hits based on identity and coverage

Quantification and Normalization

- Count filtered VF-mapped reads

- Normalize by gene length and sequencing depth to transcripts per million (TPM)

- Annotate VF clusters, mobility, bacterial host taxonomy, and VF categories [21]

Cross-Niche Comparative Analysis

- Compare VF abundance and diversity across different ecological niches

- Identify mobile VFs associated with plasmids, prophages, and integrative conjugative elements

- Attribute VFs to specific bacterial hosts at species level

Protocol 3: Machine Learning-Based Virulence Factor Prediction with PLMVF

Objective: To accurately identify novel virulence factors using protein language models and structural similarity metrics.

Methodology Details:

Feature Extraction

- Extract sequence embeddings using ESM-2 protein language model

- Generate 3D structural features using ESMFold

- Calculate true TM-scores based on protein structures [22]

Structural Similarity Prediction

- Train TM-predictor model on known structural similarities

- Predict TM-scores to capture remote homology relationships

- Concatenate ESM-2 sequence features with predicted TM-score features [22]

Ensemble Model Training

- Utilize balanced dataset (3,000 VFs and 3,000 non-VFs for training)

- Train ensemble model with combined feature set

- Apply Knowledge-Augmented Network (KAN) for final VF prediction [22]

Validation and Performance Assessment

- Test on independent dataset (576 VFs and 576 non-VFs)

- Evaluate using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score

- Compare against existing tools (VirulentPred, MP3, DeepVF, DTVF) [22]

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Comparative Genomics Workflow for Cross-Niche Virulence Analysis. This workflow outlines the key steps in identifying niche-specific virulence factors, from sample collection through to computational analysis and final gene identification.

Figure 2: MetaVF Workflow for Metagenomic Virulence Factor Profiling. This specialized workflow details the process for identifying and quantifying virulence factors directly from metagenomic data, incorporating stringent filtering and comprehensive annotation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Genomic Studies of Virulence Factors

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Function | Application Context | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| VFDB 2.0 Database | Comprehensive VF reference | VF annotation in genomic and metagenomic studies | 62,332 non-redundant VF sequences; mobile VF annotation; host taxonomy [21] |

| MetaVF Toolkit | VF profiling from metagenomes | Direct VF analysis from sequencing data without cultivation | Species-level resolution; mobile genetic element association; high TDR (>97%) [21] |

| PLMVF Model | Novel VF prediction | Identification of uncharacterized VFs using AI | Incorporates structural similarity; 86.1% accuracy; remote homology detection [22] |

| CheckM | Genome quality assessment | Quality control in genome curation | Estimates completeness and contamination; essential for dataset standardization [3] |

| AMPHORA2 | Phylogenetic marker gene extraction | Phylogenetic tree construction for evolutionary analysis | 31 universal single-copy genes; robust phylogenetic framework [3] |

| Artificial Metagenomic Datasets (AMSD) | Method validation and benchmarking | Tool performance evaluation | Defined VF abundance and mutation rates; enables TSI optimization [21] |

| Prokka v1.14.6 | Rapid genome annotation | ORF prediction in bacterial genomes | Standardized annotation pipeline; integrates multiple databases [3] |

Discussion: Applications and Insights from Cross-Niche Virulence Factor Studies

Comparative genomic frameworks have revealed fundamental insights into how bacterial pathogens adapt to different ecological niches through distinct genetic strategies. Human-associated bacteria, particularly from the phylum Pseudomonadota, demonstrate higher prevalence of carbohydrate-active enzyme genes and virulence factors related to immune modulation and adhesion, suggesting co-evolution with human hosts [3]. In contrast, environmental bacteria show greater enrichment in metabolic and transcriptional regulation genes, highlighting their adaptability to diverse environmental conditions. Clinical isolates exhibit higher rates of antibiotic resistance genes, particularly those conferring fluoroquinolone resistance, while animal hosts serve as important reservoirs of resistance genes [3] [2].

The integration of machine learning with comparative genomics has enabled the identification of key host-specific bacterial genes, such as hypB, which potentially plays crucial roles in regulating metabolism and immune adaptation in human-associated bacteria [3]. These findings underscore the power of comparative genomic approaches in unraveling the genetic basis of host-pathogen interactions and provide valuable evidence to inform pathogen transmission control, infection management, and antibiotic stewardship policies.

Emerging methodologies that incorporate structural similarity and remote homology detection, such as PLMVF, offer promising avenues for identifying novel virulence factors that evade detection by traditional sequence-based methods [22]. As these frameworks continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly enhance our ability to predict pathogenic potential, track virulence transmission across reservoirs, and develop targeted interventions against problematic pathogens across the One Health continuum.

The study of bacterial pathogenesis has been transformed by the advent of high-throughput sequencing and specialized bioinformatics databases. For researchers investigating the comparison of virulence factors across ecological niches, four databases stand out as indispensable tools: the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB), the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), the Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) database, and the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database (CAZy). These resources provide structured, curated knowledge that enables scientists to move beyond simple sequence analysis to functional prediction and evolutionary insight. VFDB and CARD directly catalog the genetic determinants of pathogenicity and treatment failure, while COG and CAZy provide essential functional context for genomic data, revealing how pathogens interact with their environments and hosts. Together, they form an integrated toolkit for deciphering the complex relationships between genetic content, ecological niche, and pathogenic potential, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic targets in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance.

Core Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Core Database Characteristics and Applications

| Database | Primary Focus | Year Founded | Last Update | Key Content Metrics | Primary Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFDB | Virulence Factors (VFs) & Anti-Virulence Compounds | Over 20 years ago | 2024 | 902 anti-virulence compounds from 262 studies; covers 32 medically important bacterial genera [11]. | Identifying virulence mechanisms, screening for anti-virulence drug targets, and understanding host-pathogen interactions [11]. |

| CARD | Antibiotic Resistance Genes & Mechanisms | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Predicting antibiotic resistance phenotypes from genomic data and surveillance of resistance gene dissemination. |

| COG | Phylogenetic Protein Classification & Functional Annotation | 1997 | 2025 | 4,981 COGs covering 2,296 prokaryotic genomes (2,103 bacteria, 193 archaea) [23]. | Functional annotation of genomes, evolutionary studies, and identification of core/pangenome components [24] [23]. |

| CAZy | Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes) | 1998 | 2025 | 36,364 bacterial, 587 archaeal, and 2,002 eukaryotic genomes analyzed [25] [26]. | Profiling metabolic capabilities (CAZyme), understanding nutrient acquisition, and studying host-glycan interactions [25] [27]. |

Quantitative Coverage and Taxonomic Scope

Table 2: Taxonomic and Genomic Coverage

| Database | Taxonomic Scope | Genomic Coverage | Classification System |

|---|---|---|---|

| VFDB | Focused on medically important pathogens (32 genera) [11]. | Not explicitly stated, but integrates data from public genomes. | Virulence factor categories (e.g., adhesion, biofilm, toxins) and anti-virulence compound superclasses [11]. |

| CARD | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing |

| COG | Bacteria and Archaea (primarily) [24] [23]. | 2,296 prokaryotic genomes (typically one per genus) [23]. | 4,981 Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs), grouped into functional categories and pathways [23]. |

| CAZy | All kingdoms of life (Bacteria, Archaea, Eukaryota, Viruses) [25] [26]. | 36,364 bacterial, 587 archaeal, 2,002 eukaryotic, and 501 viral genomes [26]. | Family-based classification (GHs, GTs, PLs, CEs, AAs, CBMs) [25] [27]. |

Database Integration in Experimental Research

A Standard Workflow for Comparative Genomics

Investigating virulence across ecological niches requires a structured bioinformatics workflow that integrates these databases. The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental protocol for a comparative genomic study.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The workflow above is implemented through the following detailed steps, which can be adapted for studying niche-specific adaptations:

Genome Dataset Curation: Collect high-quality genome sequences with clear metadata on isolation source (e.g., human, animal, environment). Apply stringent quality control: exclude contig-level assemblies, require high N50 (e.g., ≥50,000 bp), and ensure high completeness (≥95%) and low contamination (<5%) using tools like CheckM. Remove redundant genomes by calculating genomic distances with Mash and applying clustering (e.g., genomic distance ≤0.01) to obtain a non-redundant set [2].

Open Reading Frame (ORF) Prediction: Annotate all curated genomes using a standardized tool like Prokka to consistently identify protein-coding sequences [2].

Functional and Specialized Annotation:

- COG Annotation: Map predicted ORFs to the COG database using RPS-BLAST (e-value threshold: 0.01, minimum coverage: 70%) to assign functional categories [2].

- CAZy Annotation: Identify carbohydrate-active enzymes using dbCAN2 (or HMMER against CAZy HMM profiles with parameter

hmm_eval 1e-5) to assign ORFs to Glycoside Hydrolase (GH), GlycosylTransferase (GT), and other CAZy families [2]. - VFDB & CARD Annotation: Screen ORFs against VFDB and CARD using appropriate tools (e.g., BLAST, RPS-BLAST) with defined identity/coverage thresholds to identify virulence and antibiotic resistance genes.

Data Integration and Statistical Analysis: Merge the annotation results into a unified table. Conduct comparative analyses (e.g., ANOVA, Chi-square tests) to identify genes and functions significantly enriched in specific niches (human, animal, environment). Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forest) with functional profiles as features to build predictive models of niche adaptation and identify key genetic determinants [2].

Phylogenetic Contextualization: For evolutionary insight, construct a robust phylogenetic tree. Extract universal single-copy genes (e.g., using AMPHORA2), align them (e.g., with Muscle), concatenate the alignments, and infer a maximum-likelihood tree (e.g., with FastTree). This tree controls for phylogenetic relatedness when comparing genetic traits across niches [2].

Table 3: Key Bioinformatics Tools and Resources for Database Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Prokka | Software Tool | Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation; generates the standardized ORF calls required for downstream database searches [2]. |

| BLAST/RPS-BLAST | Algorithm/Suite | Fundamental tool for sequence similarity searching; used for mapping ORFs to COG, VFDB, and CARD [24] [2]. |

| HMMER | Software Tool | Profile Hidden Markov Model searches; provides a more sensitive method for detecting remote homologs, essential for CAZy and other family-based annotations [2] [27]. |

| dbCAN2 | Web Server/Pipeline | Automated pipeline for CAZyme annotation; integrates multiple tools including HMMER for robust assignment of sequences to CAZy families [2]. |

| CheckM | Software Tool | Assesses genome quality (completeness and contamination) which is a critical prerequisite for meaningful comparative genomics [2]. |

| Mash | Software Tool | Estimates genomic distance and performs fast genome clustering to reduce dataset redundancy and avoid phylogenetic bias [2]. |

Research Insights: Linking Database Queries to Biological Understanding

Key Findings from Integrated Database Studies

The application of these integrated databases has yielded critical insights into microbial adaptation. A large-scale comparative genomics study of 4,366 pathogen genomes, which employed COG, VFDB, and CAZy, revealed distinct niche-specific strategies [2]. Human-associated bacteria, particularly Pseudomonadota, were enriched in VFDB-derived virulence factors for immune modulation and adhesion, and CAZy-derived genes for carbohydrate-active enzymes, indicating co-evolution with the human host. In contrast, environmental bacteria showed COG enrichment in general metabolic and transcriptional regulation functions. Furthermore, the study identified specific adaptive genes like hypB in human-associated strains using this database-integrated approach [2].