Microbial Ecogenomics: Unlocking Bioremediation of Chlorinated Pollutants

Chlorinated organic compounds represent a significant global environmental threat.

Microbial Ecogenomics: Unlocking Bioremediation of Chlorinated Pollutants

Abstract

Chlorinated organic compounds represent a significant global environmental threat. This article explores how microbial ecogenomics—the application of genomics to environmental systems—is revolutionizing the bioremediation of contaminated sites. We detail the foundational science of microbial degradation, from organohalide-respiring bacteria to their metabolic pathways. The discussion covers advanced ecogenomic tools like metagenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics that enable precise monitoring and optimization of bioremediation processes. Critical challenges including microbial community dynamics, contamination stress, and functional redundancy are addressed alongside innovative troubleshooting strategies. Finally, we present validation frameworks through case studies and comparative genomic analyses, highlighting how these integrated approaches are transforming environmental management and offering insights for biomedical applications.

The Microbial Warriors: Foundational Ecology and Physiology of Organohalide Respiration

Chlorinated compounds represent one of the most significant classes of environmental pollutants worldwide due to their extensive historical use in industrial, agricultural, and domestic applications [1] [2]. These compounds exhibit concerning environmental persistence and can pose serious health threats, with many demonstrating toxic and carcinogenic properties [3]. The widespread contamination of groundwater systems, soils, and sediments by chlorinated solvents such as perchloroethene (PCE) and trichloroethene (TCE) is particularly problematic, as they form dense non-aqueous phase liquids (DNAPLs) that sink through permeable groundwater aquifers until reaching impermeable zones, creating long-term contamination sources [4] [3]. Beyond traditional solvents, emerging chlorinated contaminants including antibiotics, endocrine disrupting chemicals, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and organophosphate esters present additional challenges for environmental remediation [5].

Microbial ecogenomics has revolutionized our approach to characterizing and remediating chlorinated contaminated sites by enabling comprehensive analysis of microbial community structures, dynamics, and functions in response to environmental stimuli [1] [6]. This approach leverages high-throughput genomics technologies to elucidate key microorganisms and consortia involved in organohalide respiration, providing insights that enhance bioremediation strategies and monitoring capabilities [1]. The integration of metagenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics has been instrumental in advancing beyond culture-dependent methods, opening the microbial "blackbox" at contaminated sites and revealing novel metabolic capabilities [1] [2].

Quantitative Profile of Chlorinated Contaminants

Industrial Scale and Environmental Burden

Chlorinated solvents have witnessed steady market growth driven by applications across industrial sectors including chemicals, pharmaceuticals, paints, coatings, and cleaning products [7]. The stability and solvency power that make these compounds valuable industrially also contribute to their persistence in the environment and bioaccumulation potential [2]. The historical release of large quantities of these chemicals has resulted in pervasive global environmental contamination, with over 4,000 different halogenated hydrocarbons identified in various environmental compartments [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Prevalent Chlorinated Groundwater Contaminants

| Compound | Chemical Formula | Maximum Legal Limit in Water (μg/L) | Principal Use | DNAPL Forming |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perchloroethene (PCE) | C₂Cl₄ | 1.1 [3] | Dry cleaning, metal degreasing | Yes [3] |

| Trichloroethene (TCE) | C₂HCl₃ | 1.5 [3] | Industrial solvent, metal degreasing | Yes [3] |

| Vinyl Chloride (VC) | C₂H₃Cl | 0.5 [3] | PVC production, TCE/PCE degradation product | No |

| Chlorobenzene (CB) | C₆H₅Cl | Not specified in sources | Chemical intermediate, solvent | No [8] |

Documentated Contamination Scales

The scale of chlorinated solvent contamination is demonstrated by numerous contaminated sites worldwide. In the Val Vibrata industrial area in Central Italy, significant groundwater contamination by PCE and TCE has been documented, threatening agricultural and residential water resources [4] [3]. At this site, groundwater flow direction follows a Southeast trend, facilitating plume migration through the alluvial deposits of the Vibrata River [3]. Research indicates that chlorinated compounds with a high degree of chlorine substitution are generally more readily biotransformed under anoxic conditions but are often recalcitrant to aerobic degradation, making anaerobic bioremediation particularly important for these contaminants [1].

Table 2: Concentration Ranges of Chlorinated Compounds in Environmental Settings

| Environmental Compartment | Contaminant Class | Concentration Range | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landfill gas [8] | Chlorobenzene | 0.50–2.37 μg/m³ | Municipal solid waste |

| Groundwater [3] | PCE, TCE, degradation products | Variable, exceeding legal limits | Val Vibrata, Italy industrial area |

| Complex water matrices [5] | Emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) | 50–500 μg/L | Surface water and wastewater |

Microbial Ecogenomics Framework for Site Assessment

Ecogenomics Toolbox for Contamination Analysis

Microbial ecogenomics employs a suite of cultivation-independent approaches to study microbial communities through analysis of their genetic material, bypassing the limitations of traditional culturing techniques [1]. The ecogenomics toolbox includes metagenomics for assessing genetic composition and potential metabolic capabilities, transcriptomics for analyzing gene expression patterns, proteomics for identifying and quantifying protein expression, and quantitative PCR for targeting specific functional genes [1]. These techniques have been crucial for understanding the physiology, biochemistry, phylogeny, and ecology of organohalide respiring consortia, particularly for organisms recalcitrant to cultivation [1].

The application of these tools has revealed critical insights into microbial community structures at contaminated sites. Metagenomic approaches have been used to study microbial communities associated with wastewater treatment bioreactors, acid mine drainages, and chlorinated solvent-contaminated aquifers [1]. Through these analyses, researchers have determined that appropriate community structure plays a critical role in achieving complete dehalogenation in bioremediation systems [1]. Currently, metabolic and sensory interactions within dechlorinating consortia are being unraveled through metagenomic sequencing of both defined mixed cultures and complex site-specific microbial communities [1].

Key Microbial Players in Dechlorination

Organohalide-respiring bacteria (OHRB) facilitate the reductive dehalogenation of toxic halogenated compounds, using them as terminal electron acceptors in anaerobic respiration [1] [2]. Among these, certain bacterial genera have been identified as particularly important for bioremediation applications. Dehalococcoides, Dehalobacter, and Dehalogenimonas are recognized as key versatile strains due to their diverse dehalogenase systems capable of degrading a wide range of structural organohalides [2]. These obligate OHRB rely solely on organohalide respiration for energy metabolism, distinguishing them from non-obligate organohalide respirers that possess alternative metabolic strategies [2].

Research has demonstrated that Dehalococcoides spp. can completely dechlorinate hazardous compounds PCE and TCE via DCE and VC to the non-toxic terminal product ethene [3]. Some strains, such as Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain BTF08, encode up to 20 different reductive dehalogenases, with some strains containing all three enzymes necessary to couple the complete reductive dechlorination of PCE to ethene to growth [3]. The genes encoding TCE and VC reductive dehalogenases are often located within mobile genetic elements, suggesting recent horizontal acquisition and potential for microbial community adaptation to contamination [3].

Application Notes: Ecogenomics-Enhanced Remediation Protocols

Protocol 1: Microcosm Setup for Assessing Native Dechlorination Potential

Purpose: To evaluate the natural dechlorination capacity of site materials and determine appropriate biostimulation strategies [4] [3].

Materials and Methods:

- Sample Collection: Collect aquifer materials using disposable bailers or direct-push techniques from monitoring wells. For soil samples, collect root zone materials for plant-assisted remediation studies [3] [8].

- Microcosm Setup: Prepare anaerobic microcosms in sealed serum bottles containing site groundwater and soil/sediment [4]. Maintain strict anaerobic conditions during setup using an oxygen-free gas mixture (typically N₂/CO₂).

- Experimental Treatments:

- Monitoring: Periodically sample headspace and aqueous phases for chlorinated compound concentrations (PCE, TCE, DCE, VC), ethene, methane, and electron donor consumption.

Ecogenomics Integration: Collect parallel samples for DNA extraction to quantify Dehalococcoides and other OHRB via 16S rRNA gene targeting and functional genes (e.g., pceA, tceA, vcrA) using qPCR [3]. Metatranscriptomic analysis can reveal active dechlorination pathways.

Protocol 2: Bioaugmentation with Characterized Dechlorinating Consortia

Purpose: To implement and monitor performance of bioaugmentation cultures containing known OHRB for complete dechlorination of chlorinated ethenes.

Materials and Methods:

- Culture Selection: Select bioaugmentation cultures based on contaminant profile (e.g., cultures containing Dehalococcoides mccartyi strains for complete dechlorination to ethene) [3].

- Delivery System: Inject cultures into the contaminated aquifer using direct-push technology or existing wells. For enhanced distribution, consider emulsified cultures or cultures combined with mobility-enhancing agents.

- Biostimulation Coupling: Combine bioaugmentation with electron donor addition (e.g., lactate, butyrate, or hydrogen-release compounds) to support growth and activity of introduced organisms [4] [9].

- Performance Monitoring: Track contaminant concentration reductions, production of less-chlorinated intermediates, and ultimate production of ethene.

Ecogenomics Integration: Monitor population dynamics of inoculated strains using strain-specific primers and track horizontal gene transfer of reductive dehalogenase genes through mobile genetic element analysis [3].

Protocol 3: Plant-Microbe Combined Remediation for Chlorinated Aromatics

Purpose: To enhance chlorinated aromatic compound (e.g., chlorobenzene) degradation through plant-assisted microbial remediation in shallow contaminated zones [8].

Materials and Methods:

- Plant Selection: Select appropriate plant species based on contamination profile and site conditions. Studies indicate Rumex acetosa (sorrel) shows superior enhancement of chlorobenzene degradation compared to Amaranthus spinosus L. or Broussonetia papyrifera [8].

- Field Setup: Establish vegetation in contaminated areas, ensuring root penetration into contaminated zones.

- Mechanism Enhancement: The selected plants enhance degradation through multiple mechanisms: root elongation creating preferential flow paths, oxygen diffusion creating redox gradients, and root exudates stimulating microbial activity [8].

- Performance Monitoring: Measure chlorinated compound concentrations in soil pore water, soil gas, and plant tissues over time.

Ecogenomics Integration: Analyze rhizosphere microbiome shifts using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and metabolomic profiling of root exudates. Specific compounds like triethylamine and N-methylaniline from Rumex acetosa roots have been shown to enhance the TCA cycle and nicotinamide metabolism in associated microbes [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Ecogenomics of Chlorinated Sites

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic microcosm components | Create oxygen-free environments for dechlorination studies | Assessment of native dechlorination potential [4] [3] |

| Electron donors (lactate, butyrate, yeast extract) | Provide reducing equivalents for reductive dechlorination | Biostimulation of OHRB in aquifer materials [4] [3] |

| Chlorinated compound standards | Analytical quantification and method calibration | GC-ECD analysis of PCE, TCE, DCE, VC [3] [8] |

| DNA/RNA extraction kits (for environmental samples) | Nucleic acid isolation from low-biomass samples | Metagenomic and transcriptomic analysis of dechlorinating communities [1] |

| qPCR reagents and primers | Quantification of specific OHRB and functional genes | Monitoring Dehalococcoides and reductive dehalogenase genes [3] |

| Stable isotope-labeled substrates | Tracking metabolic pathways and carbon flow | Identification of active degraders via SIP [1] |

| Bioaugmentation cultures | Source of known dechlorinating activity | Inoculation with Dehalococcoides-containing consortia [3] |

| Activated carbon amendments | Contaminant sequestration combined with biodegradation | Combined adsorption-biodegradation approaches [9] |

Integrated Remediation Strategies and Monitoring Framework

Combined Adsorption and Biodegradation Approach

An innovative approach for aquifer remediation combines the strengths of adsorption and biodegradation through the injection of micrometric activated carbon into the contaminated aquifer, creating reactive zones that reduce chlorinated solvent concentrations via adsorption while simultaneously stimulating dechlorinating biological activity through electron donor addition [9]. This technology has been successfully demonstrated at the pilot scale in Europe, with post-treatment monitoring revealing significant concentration reduction of chlorinated solvents and intense biological dechlorination activity [9]. The approach benefits from the initial rapid reduction in aqueous phase concentrations through adsorption, followed by slow release and biological degradation as the primary long-term mechanism, effectively addressing both immediate risk and long-term cleanup goals.

GIS and Multivariate Analysis for Contamination Assessment

The integration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) with multivariate statistical analysis such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) provides powerful tools for modeling contamination distribution and designing remediation strategies [4] [3]. This approach involves creating a composite geodatabase that integrates geological, hydrological, geophysical, and chemical data, serving as a "cockpit" for defining conceptual site models, designing remediation strategies, implementing pilot tests, and monitoring full-scale interventions [9]. The spatial analysis capabilities of GIS enable researchers to delineate contamination plumes, identify source zones, and optimize monitoring well networks, while multivariate statistics help identify correlations between geochemical parameters and microbial activity.

Advanced Molecular Monitoring Tools

Ecogenomics approaches have developed sophisticated monitoring tools that move beyond simple contaminant concentration measurements to assess functional potential and activity of dechlorinating communities. These include:

- CARD-FISH: Catalyzed reporter deposition fluorescence in situ hybridization for quantifying specific OHRB in environmental samples [9].

- Metagenomic sequencing: Revealing the genetic potential of microbial communities and allowing partial genome reconstruction of key players [1].

- Metatranscriptomics: Identifying actively expressed genes including reductive dehalogenases under different site conditions [1].

- Metaproteomics: Detecting and quantifying expressed proteins including functional enzymes involved in dechlorination pathways [1].

- Compound-Specific Isotope Analysis (CSIA): Tracking in situ degradation by measuring isotope fractionation during biotransformation [1].

These advanced monitoring tools provide a comprehensive understanding of remediation performance beyond what traditional chemical analysis can offer, enabling researchers to verify that contamination reduction results from biological degradation rather than mere displacement or phase transfer.

The scale of chlorinated contamination from industrial solvents to emerging pollutants presents significant technical challenges, but microbial ecogenomics provides powerful approaches for developing effective bioremediation strategies. The integration of molecular tools with traditional geochemical analysis has transformed our understanding of dechlorinating microbial communities and their functions in contaminated environments. As research advances, several promising directions are emerging, including the development of more resilient bioremediation consortia through understanding community interactions, optimization of plant-microbe partnerships for shallow contamination, and refinement of combined adsorption-biodegradation approaches for challenging sites.

Future research will likely focus on elucidating the complex interactions within dechlorinating consortia, including cross-feeding relationships and metabolic networks that support OHRB activity. Additionally, the application of machine learning approaches to integrate multi-omics data with geochemical parameters holds promise for predicting remediation outcomes and optimizing treatment strategies. As new chlorinated contaminants continue to emerge, the microbial ecogenomics framework provides a adaptable approach for developing targeted bioremediation strategies that harness the natural capacity of microorganisms to transform these persistent pollutants.

Organohalide respiration (OHR) is a unique anaerobic process where certain bacteria, known as organohalide-respiring bacteria (OHRB), utilize halogenated organic compounds as terminal electron acceptors for energy conservation and growth. This process is catalyzed by reductive dehalogenase (RDase) enzyme systems and plays a crucial role in the global halogen cycle and the bioremediation of pervasive environmental pollutants like chloroethenes, ethanes, and benzenes [10] [11] [12]. Within the framework of microbial ecogenomics—the application of genomics to environmental questions—OHR represents a key microbial function that can be monitored and optimized for the cleanup of contaminated sites. The integration of advanced molecular tools has been instrumental in moving the study of OHRB from physiological characterization in pure cultures to the management of complex microbial consortia in situ, enabling a systems-level understanding of bioremediation processes [11] [13].

Ecogenomic Frameworks and Key Microbial Players

Microbial ecogenomics provides a suite of tools for diagnosing and monitoring the potential and activity of OHRB at contaminated sites. This toolbox includes techniques such as metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and quantitative PCR (qPCR), which allow researchers to move beyond cultivation-based limitations and gain insights into the structure, function, and dynamics of dechlorinating communities in their natural environments [11] [13].

OHRB are phylogenetically diverse and are found across several bacterial phyla. They are often categorized as obligate or facultative respirers. Table 1 summarizes the key genera, their phylogenetic affiliation, and metabolic traits.

Table 1: Key Genera of Organohalide-Respiring Bacteria

| Genus | Phylum | Metabolic Type | Example Electron Acceptors | Relevance to Bioremediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dehalococcoides | Chloroflexi | Obligate | PCE, TCE, VC, PCBs | Only known genus that completely dechlorinates PCE/TCE to non-toxic ethene [11] [14] [15]. |

| Dehalobacter | Firmicutes | Obligate | PCE, TCE | Specializes in dechlorination of various chlorinated ethenes and ethanes [10] [16]. |

| Dehalogenimonas | Chloroflexi | Obligate | TCE, chlorinated alkanes | Dechlorinates TCE to ethene; found in diverse terrestrial environments [16] [15]. |

| Desulfitobacterium | Firmicutes | Facultative | PCE, chlorinated phenols | Metabolically versatile; contains multiple RDase genes; important for degrading chlorinated aromatics [10] [13]. |

| Geobacter | Proteobacteria | Facultative | TCE, chlorinated benzenes | Can couple dechlorination to the oxidation of organic compounds or metals [14] [15]. |

| Sulfurospirillum | Proteobacteria | Facultative | PCE | Often reduces PCE to cis-DCE; a model organism for studying OHR [17] [13]. |

The genetic determinants for OHR are typically organized in reductive dehalogenase (rdh) gene clusters. The core of this cluster consists of rdhA, which encodes the catalytic RDase enzyme, and rdhB, which encodes a putative membrane anchor protein [10]. The expression of these genes is often regulated by dedicated transcriptional regulators, which can be specific to a single rdh operon or control multiple operons, allowing OHRB to respond to the presence of specific organohalides [10].

Protocol: Assessing OHR Potential in Environmental Samples

The following protocol outlines a combined ecogenomics and microcosm-based approach to establish and validate the OHR potential of a contaminated environmental sample, such as sediment or groundwater [18] [15].

Materials and Equipment

- Anaerobic工作站 or Chamber: For all culture manipulations to maintain anoxic conditions.

- Bicarbonate-buffered Mineral Salt Medium: A defined, anoxic medium lacking organic carbon sources.

- Electron Donor: e.g., Sodium lactate, sodium acetate, or H2/CO2 (80:20) in the headspace.

- Target Organohalide: e.g., Tetrachloroethene (PCE) or trichloroethene (TCE).

- DNA/RNA Extraction Kit: Certified for environmental samples (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Kit).

- PCR and qPCR Thermocycler

- High-Throughput Sequencer: For 16S rRNA gene amplicon or metagenomic sequencing.

- Gas Chromatograph (GC) with appropriate detector (e.g., Flame Ionization Detector).

Procedure

Step 1: Microcosm Setup and Enrichment

- In an anaerobic chamber, dispense 50 mL of sterile, anoxic mineral salt medium into 100 mL serum bottles.

- Inoculate with 2-5 g of the environmental sample (e.g., sediment or landfill leachate) [18] [15].

- Amend the microcosm with an electron donor (e.g., 10 mM lactate) and the target organohalide (e.g., PCE at a saturating aqueous concentration or as a neat compound) [18].

- Seal the bottles with Teflon-lined butyl rubber stoppers and crimp-seal with aluminum caps.

- Incubate statically in the dark at the relevant environmental temperature (e.g., 20-30°C).

- Monitor periodically for organohalide depletion and formation of less-chlorinated daughter products (e.g., cis-DCE, VC, ethene) using GC analysis.

Step 2: Community DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

- After dechlorination activity is observed, aseptically subsample biomass from the active microcosms.

- Extract total genomic DNA using a commercial kit.

- Amplify the hypervariable V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene using universal primers (e.g., 341F and 805R) [15].

- Purify the amplicons and prepare libraries for high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina platform.

Step 3: Bioinformatics and Functional Prediction

- Process raw sequencing reads using a standard pipeline (e.g., QIIME 2 or Mothur) to generate Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs).

- Taxonomically classify ASVs against a reference database (e.g., SILVA or Greengenes) to identify potential OHRB genera (e.g., Dehalococcoides, Dehalogenimonas) [15].

- (Optional) Use phylogenetic investigation of communities by reconstruction of unobserved states (PICRUSt) to predict the metagenomic functional content, including the presence of genes for key reductive dehalogenases [15].

Step 4: Validation with qPCR To quantitatively track key OHRB, design qPCR assays targeting:

- The 16S rRNA gene of specific OHRB (e.g., Dehalococcoides spp.).

- Functional biomarker genes, particularly reductive dehalogenase genes (e.g., vcrA, bvcA for vinyl chloride reduction) [14]. An increase in gene copy numbers in the active, enriched microcosms compared to controls provides strong evidence for the growth of specific OHRB linked to dechlorination.

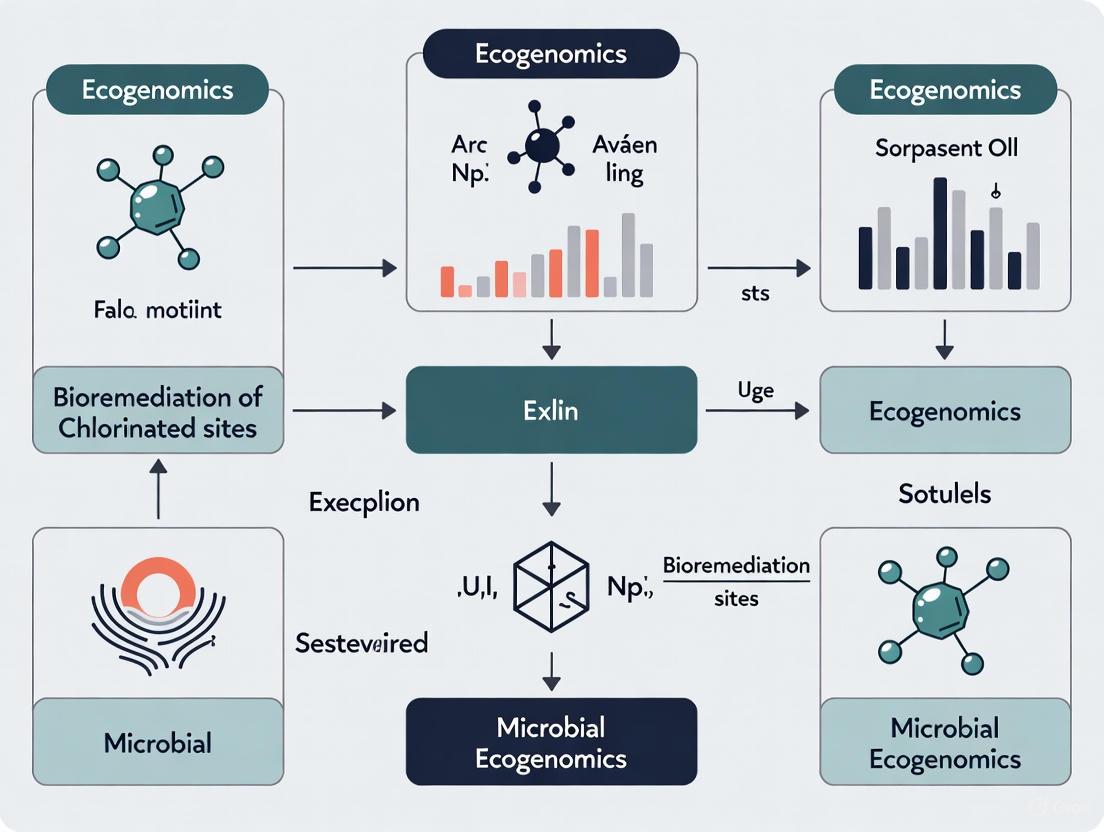

The workflow for this multi-faceted protocol is visualized below.

Diagram 1: Workflow for assessing OHR potential in environmental samples.

Protocol: Metaproteomic Analysis for In Situ Activity Confirmation

While DNA-based methods confirm the potential for OHR, detecting expressed proteins provides direct evidence of in situ activity. Shotgun metaproteomics can identify and quantify key catalytic enzymes in biomass collected from the field [14].

Materials and Equipment

- Groundwater Biomass: Concentrated via filtration or centrifugation from monitoring wells.

- Lysis Buffer: e.g., SDS-containing buffer with protease inhibitors.

- Protein Digestion Kit: Including reduction, alkylation, and tryptic digestion reagents.

- Liquid Chromatograph coupled to a Tandem Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS/MS)

- Protein Database: Containing sequences of expected OHRB (e.g., from isolate genomes or metagenome-assembled genomes).

- Proteomics Search Software: e.g., MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer.

Procedure

Step 1: Protein Extraction and Digestion

- Lyse field-collected biomass cells using a combination of chemical and mechanical methods.

- Precipitate and clean the extracted proteins.

- Reduce disulfide bonds with dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylate with iodoacetamide.

- Digest proteins into peptides using sequencing-grade trypsin.

Step 2: LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Processing

- Separate the resulting peptides using nano-flow liquid chromatography.

- Analyze eluting peptides with a high-resolution tandem mass spectrometer.

- Search the resulting MS/MS spectra against a customized protein database of OHRB and other relevant community members.

- Apply strict false-discovery rate thresholds (e.g., <1%) for peptide and protein identification.

Step 3: Data Interpretation The detection of specific RDases (e.g., VcrA, BvcA, TceA) and associated metabolic proteins (e.g., the hydrogenase HupL) provides direct evidence of the ongoing organohalide respiration process at the field site. Correlating protein abundance with RNA transcript levels from the same sample can further strengthen the evidence for active bioremediation [14].

The Regulatory Network of Organohalide Respiration

The expression of reductive dehalogenase genes is tightly regulated. In many OHRB, such as Dehalobacter and Desulfitobacterium, this regulation is mediated by transcriptional regulators of the CRP/FNR family (named RdhK) [10]. These regulators act as biosensors for specific organohalides, activating transcription of their cognate rdh operon only when the substrate is present. The mechanism of this regulatory pathway is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Transcriptional regulation model for reductive dehalogenase genes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2 details essential reagents and their applications in OHR research, crucial for both fundamental and applied studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for OHR Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use in OHR |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Mineral Medium | Provides essential nutrients in a controlled, anaerobic environment for cultivating OHRB and setting up microcosms. | Used in enrichment cultures from environmental samples and for physiological studies of isolates [18] [15]. |

| Specific Electron Donors (H₂, Lactate) | Serves as the electron source for the reductive dechlorination process. | Hydrogen is the sole electron donor for obligate OHRB like Dehalococcoides; lactate can be used by facultative OHRB and fermenters [18] [14]. |

| Chlorinated Substrates (PCE, TCE, PCBs) | Act as terminal electron acceptors to selectively enrich for and study OHRB. | PCE is used to enrich for dechlorinating communities; specific PCB congeners are used to study dechlorination pathways [18]. |

| qPCR Assays & Primers/Probes | Quantitative tracking of OHRB populations (16S rRNA genes) and functional genes (RDases) in communities. | Monitoring the growth of Dehalococcoides and the abundance of vcrA during bioremediation [13] [14]. |

| Metagenomic Sequencing Kits | Unbiased characterization of total microbial community composition and genetic potential from DNA. | Identifying novel OHRB and mapping the full complement of rdh genes in a contaminated site [11] [18]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Identification and quantification of proteins expressed in situ (metaproteomics). | Direct detection of VcrA and other RDase enzymes in field samples to confirm activity [14]. |

Quantitative Data and Trends in OHR Research

Bibliometric analyses reveal the growth and focus of scientific fields. A bibliometric study analyzing literature from 1988 to 2023 identified 1,591 publications on OHRB, showing a steady increase in research output, with a peak in publications in the past decade, underscoring the field's activity [12] [19]. Another analysis focusing on three key obligate OHRB genera (Dehalococcoides, Dehalobacter, and Dehalogenimonas) covered 899 publications from 1994 to 2024, noting that the number of publications, involved institutions, and total citations have all increased significantly, especially after 2012 [16].

Table 3: Bibliometric Summary of OHRB Research (as of 2023/2024)

| Bibliometric Parameter | Value | Context / Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Total Publications (1988-2023) | 1,591 | Steady increase since the 1980s, with a peak in the last decade [12]. |

| Publications on 3 Key Genera | 899 (1994-2024) | Research has advanced sequentially, transitioning from basic characterization to environmental application [16]. |

| Countries Contributing | 40 | Indicates global research collaboration and interest [16]. |

| Key Research Themes | Two primary foci | 1) Mechanistic exploration of OHRB. 2) Their interplay with environmental factors [12] [19]. |

The study of organohalide respiration has evolved from initial discoveries to a sophisticated ecogenomics-driven discipline. The protocols and tools outlined here—from enrichment culturing and community sequencing to metaproteomic validation—provide a robust framework for researchers to diagnose, monitor, and enhance bioremediation performance at chlorinated contaminant sites. Future research will likely focus on elucidating the ecological interactions and evolutionary pathways of OHRB, investigating dehalogenation in archaea, and harnessing synthetic biology to engineer strains with enhanced biotransformation capabilities [12] [16]. Integrating these advanced ecogenomic tools will continue to refine our understanding of this unique anaerobic metabolism and its critical application in restoring contaminated environments.

Microbial ecogenomics has revolutionized our understanding of bioremediation by enabling system-level analysis of microbial communities at contaminated sites. The application of genomics, metagenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics approaches has been particularly transformative for studying organohalide-respiring bacteria (OHRB) that transform persistent chlorinated pollutants into less harmful compounds [11]. Among these OHRB, three bacterial genera stand out as keystone players in reductive dechlorination processes: Dehalococcoides, Dehalobacter, and Desulfitobacterium. These organisms have evolved specialized metabolic capabilities to utilize chlorinated compounds as terminal electron acceptors in anaerobic respiration, playing pivotal roles in the detoxification of widespread groundwater contaminants such as chlorinated ethenes, ethanes, and benzenes [20] [21] [11]. This application note examines the ecogenomics of these key bacterial players, providing detailed protocols for their study and application in bioremediation research within the broader context of microbial ecogenomics for contaminated site restoration.

Comparative Ecogenomics of Key Organohalide-Respiring Bacteria

Metabolic Traits and Genomic Features

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key organohalide-respiring bacterial genera

| Characteristic | Dehalococcoides | Dehalobacter | Desulfitobacterium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Chloroflexi | Firmicutes | Firmicutes |

| Genome Size (Mb) | ~1.4 [22] | Information missing | 5.3 (D. hafniense DCB-2) [23] |

| Metabolic Lifestyle | Obligate OHRB [24] [22] | Obligate OHRB [21] | Metabolically versatile [23] |

| Electron Donors | H₂ [24] | H₂ [20] | H₂, lactate, pyruvate, butyrate [23] |

| Chlorinated Substrate Range | Chlorinated ethenes, benzenes, dioxins [24] | Chloroethanes, chloromethanes, chlorobenzenes [20] [21] | Chlorophenols, chloroethenes [23] |

| Reductive Dehalogenase Diversity | 11-24 RdhA genes per genome [25] | 23 full-length RdhA homologs in strain TeCB1 [20] | 7 RdhA genes in D. hafniense DCB-2 [23] |

| Cobalamin Biosynthesis | Partial pathway; requires exogenous corrinoids [24] [22] | Information missing | Complete pathway predicted [23] |

| Environmental Distribution | Contaminated groundwater worldwide [26] [25] | Diverse contaminated sites [20] [21] | Soil, sediment, contaminated sites [23] |

Ecological Roles in Contaminated Environments

These OHRB occupy distinct but complementary niches in contaminated ecosystems. Dehalococcoides strains are particularly crucial for complete dechlorination of chloroethenes to non-toxic ethene, with some strains expressing vinyl chloride-reducing RDases (BvcA, VcrA) essential for preventing carcinogen accumulation [26] [27]. Dehalobacter strains demonstrate remarkable specialization in respiring highly chlorinated alkanes including 1,1,1-trichloroethane and chloroform, pollutants that often co-occur with chloroethenes at industrial sites [21]. Desulfitobacterium spp. exhibit broader metabolic versatility, capable of utilizing diverse electron acceptors including metals and sulfur compounds alongside chlorinated organics, potentially facilitating biogeochemical cycling beyond dehalogenation [23].

The functional redundancy observed across these genera enhances ecosystem resilience, as multiple community members may perform similar dechlorination steps [22] [11]. Ecogenomic studies reveal that dechlorinating consortia stability depends more on functional capabilities than taxonomic composition, explaining why different OHRB assemblages can achieve similar remediation outcomes at distinct contaminated sites [22].

Experimental Protocols for Ecogenomics Investigation

Protocol 1: Cultivation and Enrichment of OHRB from Contaminated Samples

Principle: Anaerobic cultivation selectively enriches OHRB using chlorinated compounds as terminal electron acceptors and H₂ as electron donor [20] [21].

Materials:

- Anaerobic mineral salts medium [20] [21]

- Electron donor: H₂ (20% headspace) or organic donors (lactate, butyrate, methanol) [20] [22]

- Electron acceptor: Chlorinated compound (e.g., PCE, TCE, 1,1,1-TCA, chlorobenzene) [20] [21]

- Reducing agent: Ti(III) citrate or amorphous FeS [20] [21]

- Vitamin solution including vitamin B₁₂ [20] [21]

Procedure:

- Prepare anaerobic medium under N₂/CO₂ (80:20) atmosphere using standard anaerobic techniques

- Add electron acceptor: 80μM for soluble compounds or excess solid (40mg) for poorly soluble compounds [20]

- Inoculate with contaminated sediment or groundwater (1-10% v/v) [20] [21]

- Amend with electron donor (H₂ in headspace or 5mM organic donor) [20]

- Incubate statically at 30°C in the dark [20]

- Monitor dechlorination products and chloride release via GC and ion chromatography

- Transfer culture (1-10% v/v) to fresh medium upon observed dechlorination

Troubleshooting:

- If dechlorination stalls, check H₂ availability and redox potential

- For chlorinated alkane dechlorination, consider Dehalobacter-specific conditions [21]

- If culture produces vinyl chloride without further degradation, screen for Dehalococcoides with vcrA or bvcA genes [26] [27]

Protocol 2: Metagenomic Sequencing and Analysis of Dechlorinating Communities

Principle: Shotgun sequencing of community DNA reveals taxonomic composition and functional potential without cultivation bias [22] [11].

Materials:

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit) [26]

- Library preparation reagents

- High-throughput sequencer (Illumina HiSeq/MiSeq)

- Bioinformatics tools: MG-RAST, PhylopythiaS, Metawatt [28] [22]

Procedure:

- Concentrate biomass from groundwater or culture by filtration (0.22μm polycarbonate filters) [26]

- Extract genomic DNA using standardized protocols

- Prepare sequencing library with appropriate insert sizes (3kb, 35kb) [22]

- Sequence using Illumina platform (100bp paired-end reads recommended) [28]

- Quality filter and assemble reads using "pga.lucy" assembler or comparable tools [22]

- Annotate contigs using MG-RAST server for functional profiling [22]

- Bin contigs to specific taxonomic groups using tetranucleotide frequency and coverage [28]

- Identify reductive dehalogenase genes by homology search [22]

Analysis:

- Compare metabolic pathway completeness across community members

- Identify potential syntrophic interactions (corrinoid synthesis, H₂ production) [22]

- Phylogenetically classify RDase genes to determine dechlorination potential [22]

Protocol 3: Targeted Proteomics for Detection of Dechlorination Activity

Principle: Liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring-mass spectrometry (LC-MRM-MS) enables sensitive detection and quantification of key reductive dehalogenase enzymes as biomarkers of dechlorination activity [25].

Materials:

- LC-MRM-MS system (triple quadrupole mass spectrometer)

- Trypsin for protein digestion

- Synthetic peptide standards

- C18 reverse-phase chromatography column

- Groundwater sampling filters (0.22μm)

Procedure:

- Concentrate biomass from groundwater by filtration [25]

- Extract proteins using denaturing buffer (e.g., 8M urea)

- Digest proteins with trypsin (1:50 enzyme:substrate, 37°C, 16h)

- Spit sample: one aliquot for global proteomics, one for targeted MRM

- For global proteomics: analyze by high-mass-accuracy LC-MS/MS

- For targeted proteomics: a. Select proteotypic peptides from RDases and housekeeping proteins [25] b. Develop MRM transitions for each peptide c. Optimize collision energies for each transition d. Analyze samples using scheduled MRM methods

- Confirm peptide identities by matching retention times and fragmentation patterns to standards [25]

Target Peptides:

- Housekeeping proteins: GroEL, EF-TU, rpL7/L2 [25]

- General dechlorination biomarker: FdhA (formate dehydrogenase) [25]

- Specific RDases: TceA, BvcA, VcrA for chloroethene degradation [25]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for OHRB investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ti(III) citrate | Chemical reductant for maintaining anaerobic conditions | Dehalobacter cultivation [20] |

| Amorphous FeS | Alternative chemical reductant | Dehalobacter isolation [20] |

| Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) | Slow-release electron donor source | Biostimulation in groundwater [26] |

| Vitamin B₁₂ | Essential corrinoid cofactor for RDases | Dehalococcoides pure culture [24] [22] |

| Bicarbonate-buffered mineral medium | Growth medium for anaerobic cultivation | OHRB enrichment cultures [20] [21] |

| Chlorinated compound standards | Analytical standards for monitoring dechlorination | GC calibration for PCE, TCE, cis-DCE, VC [26] |

| Synthetic peptide standards | Quantification standards for targeted proteomics | RDase protein detection in groundwater [25] |

| PowerSoil DNA Extraction Kit | Standardized DNA extraction from environmental samples | Metagenomic analysis [26] |

Advanced Ecogenomics Applications

Multi-Omics Integration for Mechanistic Insights

Integrating multiple omics approaches provides unprecedented insights into dechlorination mechanisms. A recent multi-omics study of Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain CWV2 combined genomics, transcriptomics, translatomics (Ribo-Seq), and proteomics to elucidate the molecular response during TCE dechlorination [27]. This approach revealed upregulation of DNA repair and porphyrin metabolism pathways alongside RDase expression, suggesting cellular adaptation to reductive dechlorination stress [27]. Blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) coupled with mass spectrometry enabled identification of membrane-bound enzyme complexes, including the functional OHR complex comprising RDase, hydrogenase, and Fe-S molybdoenzyme components [27].

Ecogenomics-Informed Bioremediation Strategies

Ecogenomics findings have directly influenced bioremediation practice. The discovery that different Dehalococcoides strains possess unique RDase complements explains why complete dechlorination to ethene requires specific strain assemblages [27] [22]. Monitoring programs now routinely track functional genes (rdhA) rather than just taxonomic markers, enabling more accurate prediction of dechlorination potential [26] [25]. The recognition that Dehalobacter and Desulfitobacterium can respire chlorinated alkanes that inhibit Dehalococcoides has led to sequenced treatment approaches where different OHRB groups are targeted sequentially [21].

The ecogenomics framework has fundamentally transformed our understanding of Dehalococcoides, Dehalobacter, and Desulfitobacterium as key bacterial players in chlorinated site bioremediation. Integration of metagenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic approaches reveals not only the genetic potential of these organisms but also their functional activities and ecological interactions within microbial communities. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust tools for investigating these important OHRB, enabling more effective bioremediation strategies based on comprehensive understanding of microbial structure-function relationships. As ecogenomics technologies continue to advance, particularly in single-cell analysis and multi-omics integration, our ability to predict, monitor, and enhance bioremediation performance at chlorinated sites will continue to improve, ultimately leading to more efficient and reliable restoration of contaminated environments.

Microbial ecogenomics has revolutionized our understanding of the complex microbial communities responsible for degrading chlorinated pollutants in contaminated environments. By integrating high-throughput genomics technologies with microbial physiology studies, researchers can now elucidate the structural and functional relationships within dechlorinating consortia at a systems level [1] [29]. This application note examines the specialized ecological strategies of organohalide-respiring bacteria (OHRB), focusing on the stark contrasts between obligate (specialist) and facultative (generalist) dechlorinators. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for designing effective bioremediation strategies that leverage the unique capabilities of each group, particularly when managing sites contaminated with persistent chlorinated organic pollutants (COPs) like trichloroethene (TCE) and γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH) [30] [31].

Comparative Genomic and Metabolic Features

The fundamental distinction between obligate and facultative dechlorinators lies in their metabolic versatility and genomic architecture. Obligate OHRB, such as Dehalococcoides, Dehalogenimonas, and Dehalobacter, exhibit extreme specialization, relying exclusively on organohalide respiration for energy conservation [30]. In contrast, facultative OHRB including Desulfitobacterium, Sulfurospirillum multivorans, and Geobacter lovleyi can utilize multiple electron acceptors beyond chlorinated compounds [30].

Table 1: Genomic and Metabolic Characteristics of Obligate vs. Facultative Dechlorinators

| Characteristic | Obligate OHRB (Specialists) | Facultative OHRB (Generalists) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Energy Metabolism | Exclusively organohalide respiration | Organohalide respiration plus alternative pathways |

| Electron Transport Chain | Quinone-independent [30] | Quinone-dependent [30] |

| Genome Size | Reduced | Larger, more versatile |

| Metabolic Versatility | Limited to organohalide respiration | Multiple respiratory pathways |

| Cultivation Requirements | Fastidious, slow growth [30] | Less restrictive, easier to cultivate [30] |

| Examples | Dehalococcoides mccartyi, Dehalogenimonas, Dehalobacter [30] | Sulfurospirillum multivorans, Geobacter lovleyi, Desulfitobacterium [30] |

| Energy Conservation | Proposed transport-coupled phosphorylation [30] | Electron transport to quinones [30] |

| Environmental Prevalence | Low abundance, highly specialized niches [30] [32] | More frequently identified in diverse environments [30] |

Table 2: Distribution of Key Functional Genes in Isolated Dechlorinating Strains

| Strain | Classification | Dehalogenase Genes | Cobalamin Biosynthesis | Pollutants Degraded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hungatella sp. CloS1 | Non-obligate | Present | Present [30] | γ-HCH [30] |

| Enterococcus avium PseS3 | Non-obligate | Present | Present [30] | γ-HCH [30] |

| Petrimonas sulfuriphila PET | Non-obligate | Present | Present [30] | γ-HCH [30] |

| Robertmurraya sp. CYTO | Non-obligate | Present | Present [30] | γ-HCH [30] |

| Desulfitobacterium sp. THU1 | Facultative | Two reductive dehalogenases (RdhA) including putative pceA [33] | Not specified | TCE to cis-DCE at near-saturation concentrations [33] |

The genomic basis for these metabolic differences is evident in electron transport pathways. Obligate OHRB utilize quinone-independent electron transport, with energy conservation potentially occurring via transport-coupled phosphorylation associated with electron transfer to organohalide reduction [30]. In contrast, facultative OHRB employ quinone-dependent electron transport pathways where energy is conserved during electron transfer to quinones [30]. This fundamental metabolic distinction explains why quinone compounds can enhance dehalogenation efficiency in non-obligate OHRB but not in obligate OHRB like Dehalococcoides mccartyi [30].

Diagram 1: Contrasting electron transport mechanisms in obligate and facultative organohalide-respiring bacteria. Obligate OHRB utilize specialized quinone-independent pathways, while facultative OHRB employ versatile quinone-dependent electron transport that also supports alternative metabolic pathways.

Ecogenomic Insights from Contaminated Sites

Field studies at contaminated sites have revealed distinct distribution patterns and ecological behaviors of specialist versus generalist dechlorinators. At a decommissioned pharmaceutical-chemical site in China, Desulfuromonas, Desulfitobacterium, and Desulfovibrio (facultative dechlorinators) were widely detected, while the obligate Dehalococcoides appeared exclusively in deep soils [32]. Network analysis demonstrated positive correlations between these dechlorinators and BTEX-degrading and fermentative taxa, suggesting cooperative interactions in pollutant degradation [32].

The application of ecogenomics tools has been particularly valuable for understanding in situ microbial community dynamics. Metagenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses provide insights into key genes and their regulation at contaminated sites [1]. These approaches have revealed that organohalide respiring bacteria often thrive in consortia, with intricate multispecies interactive networks supporting the dechlorination process [1] [34]. For instance, a TCE-dechlorinating community enriched from a contaminated groundwater site was predominated by Clostridia, with a phylotype most similar to the homoacetogen Acetobacterium being particularly abundant [34]. This suggests potential synergistic relationships where fermentative populations support OHRB through hydrogen and acetate production.

Experimental Protocols for Dechlorinator Research

Enrichment and Isolation of Dechlorinating Bacteria

Purpose: To establish laboratory cultures of dechlorinating bacteria from contaminated environmental samples for physiological and genomic characterization.

Materials:

- Anaerobic workstation (e.g., with atmosphere of 90% N₂, 5% CO₂, 5% H₂)

- Sterile serum bottles or anaerobic tubes

- Reducing agents (e.g., cysteine-HCl, sodium sulfide)

- Vitamin and mineral supplements

- Chlorinated pollutant stock solutions (e.g., TCE, γ-HCH)

- Electron donors (e.g., sodium lactate, hydrogen)

Procedure:

- Collect environmental samples (sediment, groundwater) from contaminated sites using aseptic techniques [30] [34].

- Prepare anaerobic medium with appropriate electron acceptors and donors under oxygen-free conditions [34].

- Inoculate medium with environmental samples and amend with target chlorinated pollutant.

- Incubate statically at temperature matching in situ conditions (e.g., 12°C for groundwater systems) [34].

- Monitor dechlorination activity through regular sampling and analysis of chlorinated compounds and daughter products.

- Once dechlorination is established, transfer culture to fresh medium (typically 1-10% inoculum) to enrich for dechlorinating populations.

- For isolation, employ serial dilution-to-extinction in solid or semi-solid media or use targeted separation techniques like fluorescence-activated cell sorting [30].

Notes: Obligate OHRB typically require longer incubation times due to slower growth rates. The addition of fermented supernatant from mixed cultures can sometimes stimulate growth of fastidious dechlorinators.

Microbial Community Analysis via 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

Purpose: To characterize microbial community structure and dynamics in enrichment cultures or environmental samples.

Materials:

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit)

- PCR reagents and primers targeting V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene

- Illumina MiSeq platform or equivalent

- Bioinformatics tools (e.g., Trimmomatic, MEGAHIT, MetaBAT2) [35]

Procedure:

- Extract genomic DNA from samples, ensuring representative cell lysis.

- Assess DNA purity and concentration using agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry [32].

- Amplify 16S rRNA gene regions using appropriate barcoded primers.

- Purify and normalize amplicons before pooling for sequencing.

- Sequence using Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 300 bp paired-end reads recommended) [32].

- Process raw sequences through quality filtering, chimera removal, and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering.

- Perform taxonomic assignment using reference databases (e.g., SILVA, RDP).

- Conduct statistical analyses to compare community composition across samples and correlate with environmental parameters.

Notes: This protocol successfully identified a novel Desulfitobacterium population (strain THU1) in a TCE-dechlorinating community, revealing its dominance at high TCE concentrations [33].

Genomic Analysis of Dechlorinating Isolates

Purpose: To identify key genetic determinants of dechlorination capacity and metabolic features in bacterial isolates.

Materials:

- High-quality genomic DNA from pure cultures

- Library preparation kit for whole-genome sequencing

- Illumina or PacBio sequencing platform

- Bioinformatics tools for genome assembly and annotation (e.g., Prodigal, CheckM, GTDB-Tk) [30] [35]

Procedure:

- Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from well-characterized dechlorinating isolates.

- Prepare sequencing libraries according to platform specifications.

- Sequence genomes using appropriate coverage (typically ≥50×).

- Assemble reads into contigs and assess completeness and contamination using single-copy marker genes [30] [35].

- Annotate genomes for protein-coding genes, rRNA, tRNA, and other features.

- Specifically identify reductive dehalogenase genes and associated genetic machinery.

- Annotate metabolic pathways for energy conservation, electron transport, and stress response.

- Conduct comparative genomic analyses against reference organisms.

Notes: This approach revealed two reductive dehalogenases (RdhA) in Desulfitobacterium strain THU1, including a putative pceA, along with stress response proteins that enable tolerance to high TCE concentrations [33].

Stress Tolerance and Bioremediation Applications

Certain facultative dechlorinators exhibit remarkable tolerance to environmental stressors that would inhibit obligate specialists. A recently discovered Desulfitobacterium-containing culture demonstrated the ability to dechlorinate TCE to cis-DCE at aqueous concentrations as high as 8.0 mM, approaching saturation levels (8.4 mM) that are generally considered toxic to OHRB [33]. Genomic analysis of the dominant Desulfitobacterium strain THU1 revealed proteins involved in stress response and regulatory pathways that enable this exceptional tolerance [33].

This stress tolerance has significant implications for bioremediation of source zones with dense non-aqueous phase liquids (DNAPL), where aqueous contaminant concentrations can be extremely high. The ability of these generalist dechlorinators to function at near-saturation concentrations suggests their potential use as candidates for source zone bioremediation, enhancing the dissolution of TCE DNAPL by increasing the concentration gradient at the DNAPL-water interface [33].

Table 3: Stress Tolerance and Bioremediation Applications

| Organism Type | Tolerance to High COP Concentrations | Key Adaptive Features | Bioremediation Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obligate OHRB | Generally sensitive to high concentrations | Limited stress response systems | Plume remediation where concentrations are lower |

| Facultative OHRB | Some tolerate near-saturation concentrations (e.g., Desulfitobacterium strain THU1 tolerates 8.0 mM TCE) [33] | Stress response proteins, regulatory pathways [33] | Source zone remediation where concentrations are highest |

| Non-obligate Organochlorine-Degrading Bacteria | Variable, generally more robust | Diverse metabolic capabilities, general stress responses | Complex, heterogeneous environments |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Dechlorinator Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorinated Pollutant Standards | Analytical quantification and culture amendment | γ-HCH (lindane), TCE, PCE, cis-DCE, VC; HPLC or analytical grade [30] |

| Electron Donors | Support microbial growth and dechlorination activity | Sodium lactate, hydrogen, pyruvate, acetate [31] [34] |

| Anaerobic Culture Media | Maintain anoxic conditions for OHRB growth | Vitamin and mineral supplements, reducing agents (cysteine-HCl, sodium sulfide) [34] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Microbial community DNA isolation | PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, ZR Soil Microbe DNA MiniPrep [35] [32] |

| PCR Reagents | Target gene amplification for community analysis | Primers for 16S rRNA genes, reductive dehalogenase genes; high-fidelity polymerases [32] |

| Metagenomic Sequencing Platforms | Community structure and functional potential assessment | Illumina NovaSeq 6000, NextSeq 500, MiSeq [35] [32] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Data processing and analysis | MEGAHIT (assembly), MetaBAT2 (binning), CheckM (quality assessment), GTDB-Tk (taxonomy) [30] [35] |

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for characterizing dechlorinating microorganisms from environmental samples to bioremediation applications, combining cultivation-dependent and cultivation-independent approaches.

The strategic application of both specialist and generalist dechlorinators offers promising avenues for enhanced bioremediation of chlorinated contaminated sites. While obligate OHRB like Dehalococcoides often achieve complete dechlorination of pollutants like TCE to non-toxic ethene, their fastidious growth requirements and sensitivity to environmental stressors can limit their effectiveness in some scenarios [30] [34]. In contrast, facultative OHRB generally exhibit greater metabolic flexibility, easier cultivation, and in some cases, superior stress tolerance [30] [33].

Ecogenomic approaches will continue to be essential for elucidating the complex interactions within dechlorinating communities and identifying novel organisms with desirable traits. The isolation of four non-obligate organochlorine-degrading strains (Hungatella sp. CloS1, Enterococcus avium PseS3, Petrimonas sulfuriphila PET, and Robertmurraya sp. CYTO) with demonstrated γ-HCH degradation capability expands the toolkit available for bioremediation [30]. Future research should focus on developing synthetic consortia that leverage the complementary strengths of both specialist and generalist dechlorinators, potentially enabling more robust and complete degradation of complex contaminant mixtures across diverse environmental conditions.

Within the framework of microbial ecogenomics, the bioremediation of chlorinated ethenes is understood not as the action of a single organism, but as the result of complex, collaborative microbial networks. The core challenge in remediating sites contaminated with trichloroethene (TCE) and other chlorinated solvents lies in achieving complete reductive dechlorination to non-toxic ethene. This process is often stalled at toxic intermediates like vinyl chloride (VC) if the requisite microbial consortia are not present or properly supported [36] [1]. Only certain keystone organisms, notably Dehalococcoides (DHC) strains, possess the full enzymatic machinery to perform this complete transformation, but they are obligate symbionts, relying entirely on other community members for essential nutrients and energy precursors [36] [37]. Microbial ecogenomics—using tools like 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing, metagenomics, and co-occurrence network analysis—allows researchers to move beyond a census of what is present to a functional understanding of how these communities are assembled and how they operate [1] [38]. This Application Note details how to cultivate, monitor, and optimize these consortia for reliable and successful bioremediation.

Key Microbial Players and Interactions in Dechlorinating Consortia

Keystone Organohalide-Respiring Bacteria (OHRB)

The reductive dechlorination process is driven by diverse OHRB, which utilize chlorinated compounds as terminal electron acceptors in an anaerobic respiration process known as organohalide respiration [1] [37]. These bacteria can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Obligate OHRB: These organisms rely solely on organohalide respiration for growth. They are primarily found within the phyla Chloroflexi (e.g., Dehalococcoides) and Firmicutes (e.g., Dehalobacter). Critically, only some Dehalococcoides strains can perform the complete dechlorination of TCE to ethene [37].

- Facultative OHRB: These bacteria, including members of the genera Desulfitobacterium, Geobacter, and Sulfurospirillum, can dechlorinate compounds but also utilize other metabolic pathways and electron acceptors. They often dechlorinate TCE only to cis-DCE [37].

Syntrophic Partnerships and Metabolic Interdependence

The success of a dechlorinating consortium hinges on intricate syntrophic interactions where different microbial populations exchange metabolic products.

- Electron Donor Provision: Fermentative bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas, Desulfovibrio) break down complex organic substrates like lactate, producing hydrogen (H₂) and acetate, which serve as the direct electron donor and carbon source, respectively, for Dehalococcoides [36] [39].

- Cofactor Supply: Dehalococcoides requires corrinoids (e.g., vitamin B12) as essential cofactors for its reductive dehalogenase (RDase) enzymes. Certain community members, including Acetobacterium and other acetogens, are crucial producers and suppliers of these cobamides [39] [40].

- Toxin Mitigation: Recent studies reveal novel interactions, such as Acetobacterium consuming and detoxifying carbon monoxide (CO) that can accumulate from the incomplete Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of Dehalococcoides, thereby protecting the dechlorinating population [39].

Table 1: Key Microbial Genera in Dechlorinating Consortia and Their Functional Roles

| Microbial Genus/Group | Classification | Primary Role in Consortium | Example Metabolic Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dehalococcoides | Obligate OHRB | Complete dechlorination to ethene | Reductive dechlorination using H₂ |

| Dehalobacter | Obligate OHRB | Partial dechlorination (e.g., to cis-DCE) | Organohalide respiration |

| Desulfitobacterium | Facultative OHRB | Partial dechlorination | Versatile organohalide respiration |

| Desulfovibrio | Fermenter | Electron donor production | Lactate fermentation to H₂/acetate |

| Acetobacterium | Acetogen | Cofactor supply, CO detoxification | Cobamide production, CO oxidation |

| Pseudomonas | Keystone population | Community stability, metabolite exchange | Identified as a keystone taxon [36] |

The diagram below illustrates the core metabolic interactions and electron flow within a synergistic dechlorinating consortium.

Application Notes: Optimizing Consortia Performance

Influence of pH on Community Structure and Function

pH is a powerful environmental filter that shapes the dechlorinating microbiome. While most known OHRB are neutrophilic, successful dechlorination has been observed under moderately acidic conditions (pH ~6.2), contingent on the assembly of an adapted microbial community [37]. Ecogenomic studies reveal that these low-pH-performing consortia exhibit distinct characteristics:

- Enhanced Commensalism: Microbial networks at low pH show a higher degree of positive co-occurrence, suggesting strong cooperative interactions that stabilize the community under stress [37].

- Functional Redundancy: A higher diversity of OHRB and fermentative populations provides resilience, ensuring that critical functions are maintained even if some members are inhibited [37].

- Key Taxa: The presence of specific, low-pH-tolerant fermenters like Sedimentibacter is often correlated with superior dechlorination performance at pH 6.2, as they maintain essential H₂ and acetate production [37].

Substrate Selection for Biostimulation

The choice of electron donor is a critical biostimulation decision that directly influences consortium structure and dechlorination dynamics.

- Lactate: A rapidly fermented soluble substrate that provides a quick release of H₂, effectively stimulating dechlorination. Its use has been shown to establish consortia with Dehalococcoides, Pseudomonas, Desulfovibrio, and Methanofollis as key members [36].

- Emulsified Oils (e.g., Vegetable Oil): Slow-release substrates that generate long-lasting reducing conditions, ideal for sustained remediation in lower-flow aquifers. They promote fermentation processes that gradually supply H₂ [37] [41].

- Carbon Monoxide (CO): An emerging, versatile substrate that can serve as both an electron donor and carbon source. Bacteria like Acetobacterium oxidize CO via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, producing H₂ and acetate that fuel Dehalococcoides in a syntrophic partnership [39].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Substrates for Biostimulation

| Substrate | Type | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Dominant OHRB Enriched |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate | Soluble | Rapid establishment of reducing conditions; uniform distribution | Requires frequent injections; can cause biofouling | Dehalococcoides, Dehalobacter [36] [41] |

| Emulsified Vegetable Oil | Slow-Release | Long-lasting effect; low operation & maintenance | Limited distribution in low permeability aquifers | Dehalococcoides, Dehalogenimonas [37] [41] |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | Gaseous | Serves as both e⁻ donor & C source; thermodynamically favorable | Potential toxicity at high concentrations; requires gas handling | Dehalococcoides (in partnership with Acetobacterium) [39] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enrichment and Maintenance of TCE-Dechlorinating Consortia

This protocol outlines the procedure for establishing stable TCE-dechlorinating microcosms from environmental samples, adapted from methodologies in the search results [36] [37] [39].

Materials

- Anaerobic Medium: A bicarbonate-buffered mineral salts medium. Contains salts (e.g., NH₄Cl, KH₂PO₄, MgCl₂), trace elements, and vitamins [36] [39].

- Reductants: L-cysteine (0.2 mM) and Na₂S·9H₂O (0.2 mM) to maintain anoxic conditions. Resazurin (1 mg/L) as a redox indicator [36].

- Electron Acceptors: Neat TCE, typically added to achieve an aqueous concentration of 0.3-0.5 mM [36] [39].

- Electron Donors: Sodium lactate (10 mM) or other substrates like CO (2 mL headspace injection) [36] [39].

- Inoculum: Contaminated soil or sediment, or activated sludge from a wastewater treatment plant [36].

- Equipment: Anaerobic chamber (N₂/H₂ or N₂/CO₂ atmosphere), 100-120 mL serum bottles, butyl rubber stoppers, aluminum crimp seals, crimper.

Procedure

- Medium Preparation: Boil and cool the anaerobic medium under a stream of N₂/CO₂ (80/20, v/v) to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Dispensing: Inside an anaerobic chamber, dispense 40-80 mL of medium into sterile serum bottles.

- Addition of Reagents: Add reductants, electron donor, and inoculum (e.g., 2-4 g soil or 2 mL sludge) to the bottles.

- Amendment with TCE: Add TCE from a neat stock using a gas-tight syringe.

- Sealing and Incubation: Seal bottles with butyl rubber stoppers and aluminum caps. Incubate statically in the dark at 30 °C.

- Monitoring and Transfer: Monitor dechlorination (TCE, DCEs, VC, ethene) and pH fortnightly. Upon complete dechlorination to ethene, transfer an aliquot (e.g., 10% v/v) to fresh medium to enrich the consortium. Repeat transfers until stable, consistent dechlorination is observed.

The workflow for establishing and analyzing these consortia is summarized below.

Protocol 2: Ecogenomic Analysis of Consortium Dynamics

This protocol describes how to track the assembly and function of dechlorinating consortia using modern ecogenomic tools [36] [1] [38].

DNA Extraction and Amplicon Sequencing

- Sampling: Collect biomass from microcosms at different time points (e.g., initial, mid-, and final-dechlorination) by filtration onto 0.22 μm membranes.

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial soil DNA kit (e.g., EZNA Soil DNA Kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions [36].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplify the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4 region) and perform high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina platform [36] [37].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for Functional Genes

- Targets: Quantify absolute abundances of key genes, including:

Co-occurrence Network Analysis

- Inference: Use tools like the MicNet Toolbox or an enhanced SparCC algorithm to infer microbial associations from abundance data, generating a co-occurrence network [38].

- Analysis: Calculate network properties (modularity, connectivity) and centralities (degree, betweenness) to identify keystone taxa (e.g., Pseudomonas, Desulforhabdus) that may be critical for consortium stability [36] [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Dechlorination Consortium Research

| Reagent/Kits | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| EZNA Soil DNA Kit | DNA extraction from complex environmental samples | Isolating high-quality metagenomic DNA from soil/sludge inocula for sequencing [36] |

| Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq Platforms | High-throughput 16S rRNA amplicon & metagenomic sequencing | Profiling microbial community structure and functional potential in consortia [36] [43] |

| qPCR Assays for Dehalococcoides 16S rRNA & RDase genes | Absolute quantification of key OHRB and their functional genes | Tracking the growth of dechlorinators and the expression of dechlorination pathways [36] [42] |

| SparCC Algorithm / MicNet Toolbox | Inference of microbial co-occurrence networks from compositional data | Identifying keystone species and microbial interactions driving community assembly [36] [38] |

| Anaerobic Chamber (Coy Lab) | Creation of oxygen-free environment for culturing | Setup and maintenance of strict anaerobic microcosms and enrichment cultures [39] |

Halogenated organic compounds (HOCs) represent a significant class of environmental chemicals that exist at the intersection of natural biological processes and anthropogenic pollution. While traditionally considered primarily as industrial pollutants, over 8000 naturally occurring HOCs have been identified, revealing a complex biogeochemical halogen cycle where microorganisms play a dual role in both synthesis and degradation [44] [45]. This application note examines the complete halogen cycle within the framework of microbial ecogenomics, providing researchers with quantitative data and standardized protocols for investigating microbial halogen transformation potentials in contaminated environments. Understanding these processes is crucial for developing effective bioremediation strategies for chlorinated sites, as microbial communities possess remarkable catabolic versatility to degrade diverse HOCs through specialized enzymatic machinery [46] [11].

The interplay between natural halogen production and anthropogenic pollution creates complex dynamics in environmental systems. Natural halogenation processes occur extensively in forest soils, marine environments, and freshwater systems, while anthropogenic inputs from industrial activities, pesticides, and herbicides have significantly altered the global halogen cycle [44] [45]. Microorganisms have evolved diverse enzymatic mechanisms to both produce and degrade HOCs, including hydrolytic, reductive, oxidative, and glutathione-dependent dehalogenases [46]. This document provides a comprehensive methodological framework for investigating these processes, enabling researchers to accurately assess microbial community structure and function at contaminated sites.

Quantitative Analysis of Halogen Cycling Potential

Microbial Gene Abundance in Aquatic Systems

Table 1: Relative abundance of dehalogenase and halogenase genes in Yangtze River microbial communities

| Gene Type | Specific Enzyme | Relative Abundance (GPM) | Dominant Microbial Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dehalogenases | Haloacid dehalogenase | 45.2 | Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota |

| Haloalkane dehalogenase | 38.7 | Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota | |

| Reductive dehalogenase | 22.4 | Chloroflexi, Deltaproteobacteria | |

| 2-Haloacid dehalogenase | 18.9 | Pseudomonadota | |

| Halogenases | Tryptophan halogenase | 12.3 | Actinomycetota |

| Non-heme haloperoxidase | 8.5 | Pseudomonadota |

Recent metagenomic analysis of the Yangtze River water system revealed that dehalogenase genes substantially outnumber halogenase genes, with haloacid and haloalkane dehalogenases being most prevalent [44]. The relative abundance of dehalogenase genes was higher than that of halogenase genes, indicating a microbial community primarily oriented toward degradation rather than synthesis of HOCs [44] [47]. Among microorganisms with halogen transformation capabilities, Pseudomonadota and Actinomycetota dominated the microbial community, with some taxa possessing both halogenation and dehalogenation functions [44].

Atmospheric Halogen Impacts on Oxidation Capacity

Table 2: Impact of short-lived halogens (SLH) on atmospheric oxidants under present-day conditions

| Atmospheric Oxidant | Concentration Change with SLH | Impact on Pollutant Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl radical (OH) | -16% (global average) | Reduced degradation of methane and VOCs |

| Nitrate radical (NO₃) | -38% (global average) | Altered nighttime oxidation chemistry |

| Ozone (O₃) | -26% (global average) | Reduced secondary pollutant formation |

| Chlorine radical (Cl·) | +2632% (global average) | Enhanced VOC oxidation in coastal areas |

Short-lived halogens substantially reduce atmospheric oxidation capacity in the present-day atmosphere, particularly affecting OH and NO₃ radicals [48]. This reduction increases the lifetime and loading of key air quality and climate-relevant chemical compounds [48]. The effects show significant spatial heterogeneity due to variability in SLH emissions and their nonlinear chemical interactions with anthropogenic pollution [48].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Microbial Halogen Transformation Potential

Metagenomic Analysis of Microbial Communities

Protocol Title: Metagenomic Sequencing and Analysis of (De)halogenation Genes in Environmental Samples

Principle: This protocol enables comprehensive assessment of the genetic potential for halogen cycling in microbial communities from contaminated sites using shotgun metagenomic sequencing, allowing researchers to identify key microorganisms and functional genes without cultivation [44] [45].

Materials:

- PowerMax Soil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories) or equivalent

- Trimmomatic (v.0.39) for quality control

- metaSPAdes (v.3.15.5) for assembly

- Prodigal (v.2.6.3) for gene prediction

- CD-HIT (v.4.8.1) for creating non-redundant gene sets

- BWA (v.0.7.17) for read mapping

- CheckM (v.1.1.6) for quality assessment

- MetaBAT (v.2.12.1), CONCOCT (v.1.1.0), and DAS-Tool (v.1.1.6) for genome binning

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect environmental samples (soil, sediment, or water) aseptically from contaminated sites. For soil profiles, collect from distinguishable horizons (e.g., Of-horizon: 1-0 cm, Ah-horizon: 0-15 cm, IIP-horizon: 15-40 cm) [45].

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from 10g of soil using PowerMax Soil DNA Isolation Kit following manufacturer's instructions. Validate DNA quality and quantity using agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (260/280 nm ratio) [45].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare shotgun metagenomic libraries using appropriate kits for Illumina sequencing. Sequence with sufficient depth (recommended minimum 10 Gb per sample) [44].

- Quality Control: Process raw reads with Trimmomatic using parameters: "CROP:145, HEADCROP:10, LEADING:20, TRAILING:20, SLIDINGWINDOW:4:25, MINLEN:50" [44].

- Assembly and Gene Prediction: Assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs using metaSPAdes with -m 700 parameter. Predict coding sequences using Prodigal with -p meta flag [44].

- Functional Annotation: Create non-redundant gene set using CD-HIT with default parameters. Annotate genes against KEGG database using BlastKOALA and against UniProt database using blastp (parameters: -outfmt 5, -max-target-seqs 10) [44].

- Identification of (De)halogenation Genes: Identify reductive dehalogenase genes using the Reductive Dehalogenase Database. Select halogenase and dehalogenase protein sequences with ≥90% coverage, ≥60% identity and E values < 10−5 [44].

- Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs): Perform genome binning using MetaBAT, CONCOCT, and DAS-Tool. Retain only MAGs with completeness ≥50% and contamination ≤5% as assessed by CheckM. Dereplicate MAGs using dRep at 95% average nucleotide identity [44].

- Quantification: Map clean reads back to non-redundant gene set using BWA. Calculate relative abundance of target genes as genes per million (GPM) using Samtools to extract mapped read counts [44].

Quality Control:

- Include extraction blanks to detect contamination

- Use standard mock communities for sequencing quality assessment

- Apply consistent completeness and contamination thresholds for MAGs

- Manually curate annotation results for halogenase and dehalogenase genes

Figure 1: Metagenomic workflow for analyzing microbial halogen cycling potential in environmental samples.

Microcosm Experiments for VOX Formation Potential

Protocol Title: Quantification of Biotic Volatile Organohalogen (VOX) Formation in Soil Microcosms

Principle: This protocol measures the potential of soil microbial communities to produce volatile organohalogens through biotic processes using controlled microcosm experiments, helping researchers distinguish between biological and abiotic halogenation processes [45].

Materials:

- Gas-tight glass vials (e.g., 20 mL headspace vials)

- Gas chromatograph with mass spectrometer (GC-MS)

- Sterile deionized water

- Temperature-controlled incubator

- Native soil samples from different horizons

- Standard VOX mixtures for calibration (chloroform, bromoform, chloromethane)

Procedure:

- Microcosm Setup: Weigh 3.5 g of native soil into gas-tight glass vials. Add 8.5 mL of sterile deionized water to create a slurry [45].

- Incubation: Incubate triplicate microcosms for each soil horizon at 30°C in the dark for 1 hour [45].