Mapping the Resistome: A Comprehensive Analysis of Antibiotic Resistance Gene Distribution Across Hosts and Environments

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) represent a critical threat to global public health, circulating among humans, animals, and environmental reservoirs.

Mapping the Resistome: A Comprehensive Analysis of Antibiotic Resistance Gene Distribution Across Hosts and Environments

Abstract

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) represent a critical threat to global public health, circulating among humans, animals, and environmental reservoirs. This article provides a comprehensive synthesis for researchers and drug development professionals on the distribution, drivers, and surveillance of ARGs. Drawing on recent global metagenomic studies, we explore the foundational ecology of resistomes across diverse hosts, from wastewater treatment plants and livestock to the human gut. We then detail advanced methodological frameworks for ARG detection and annotation, troubleshoot common challenges in quantification and data analysis, and present comparative validation of tools and strategies. The goal is to equip scientists with a holistic understanding of ARG dissemination to inform smarter surveillance and countermeasure development.

The Global Resistome: Exploring ARG Diversity, Hotspots, and Key Bacterial Hosts

Core ARG Profiles in Major Environmental and Animal Reservoirs

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) represent a critical challenge to global public health. Understanding their distribution across major reservoirs is essential for evaluating health risks and developing mitigation strategies. This guide provides a comparative analysis of core ARG profiles—the set of resistance genes consistently found within a specific environment—across key animal and environmental reservoirs. By synthesizing the most current experimental data, we objectively compare the abundance, diversity, and composition of resistomes in diverse habitats, from wastewater and livestock to pristine environments. This systematic comparison, framed within a One Health context, reveals distinct resistance patterns driven by varying anthropogenic pressures and ecological factors, offering researchers and drug development professionals a evidence-based reference for risk assessment and prioritorization.

Comparative ARG Profiles Across Reservoirs

The core resistome refers to the collection of ARGs that are consistently prevalent within a specific type of environment or host. The table below synthesizes quantitative data on the abundance and diversity of ARGs in major reservoirs, highlighting the distinct profiles shaped by varying selective pressures.

Table 1: Core ARG Profiles in Major Environmental and Animal Reservoirs

| Reservoir Type | Total ARG Abundance (Relative Units) | Dominant ARG Classes | Core ARG Examples | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) [1] | High (Core ARGs comprise ~83.8% of total abundance) | Beta-lactam, Glycopeptide, Tetracycline | TetracyclineMFSEfflux_Pump, ClassB, vanT [1] | Bacterial community composition, presence of MGEs |

| Pig Manure (Conventional Farms) [2] [3] | High (Higher than antibiotic-free farms) | Aminoglycoside, Tetracycline, Beta-lactam | ANT(6)-Ib, APH(3')-IIIa, tet(40) [2] |

Direct antimicrobial exposure, farming practices |

| Pig Manure (Antibiotic-Free Farms) [3] | Lower than conventional, but still detectable (ARGs in 97% of studies) | Varies, but generally fewer dominant classes | Shared core with conventional farms (e.g., tet(40)) [2] [3] |

Environmental contamination, residual selection |

| Arctic Soils (Pristine Environment) [4] | Significantly lower (e.g., 17.7 ± 5.1 ppm) | Multidrug, Bacitracin | vanF, ceoB, bacA [4] |

Limited anthropogenic impact, natural resistome |

| Urban Coastal Waters (Shenzhen) [5] | Varies with anthropogenic influence | Aminoglycoside, Beta-lactamase, Multidrug | Genes correlated with integron intI1 [5] | Industrial discharge, sewage, recreational activities |

The core resistome in global wastewater treatment plants is remarkably consistent, featuring a core set of 20 ARGs present in every plant surveyed across six continents, which collectively account for over 80% of the total ARG abundance [1]. In contrast, livestock farming demonstrates the direct impact of antimicrobial use. While conventional and antibiotic-free farms share a core set of ARGs—ANT(6)-Ib, APH(3')-IIIa, and tet(40)—conventional farms exhibit a significantly higher likelihood of ARG detection, with a pooled odds ratio of 2.38 to 3.21 compared to antibiotic-free farms [2] [3]. This indicates that reducing antibiotics alone does not eliminate established resistance. At the other end of the spectrum, pristine environments like Arctic soils showcase a native resistome with significantly lower abundance and diversity, dominated by genes like vanF and bacA that are distinct from those associated with clinical antibiotics [4].

Experimental Methodologies for Resistome Profiling

Standardized protocols are critical for generating comparable data across resistome studies. The following section details the common workflow and key methodological approaches for core ARG profiling.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Sample collection strategies are tailored to the reservoir. For WWTPs, this involves collecting activated sludge from the aeration tank [1]. In animal studies, fresh manure is collected from rearing pens [2]. In environmental studies, soil, sediment, or water samples are collected using sterile equipment from pre-defined transects [4] [5]. A key step is the preservation of samples on dry ice or at -80°C immediately after collection to prevent microbial community shifts. DNA extraction typically uses commercial kits, such as the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen), designed to efficiently lyse a wide range of microbial cells and isolate high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA suitable for downstream molecular analysis [6].

Metagenomic Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing on platforms like Illumina NovaSeq is the gold standard for comprehensive resistome characterization [2] [1]. Following DNA extraction and library preparation, sequencing generates millions of short reads. The bioinformatic workflow involves:

- Quality Control & Assembly: Raw reads are filtered for quality and adapter sequences using tools like Trimmomatic or Sickle, then assembled into longer contigs using assemblers like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes [2] [1].

- ORF Prediction & Gene Annotation: Open Reading Frames (ORFs) are predicted from contigs using Prodigal. These ORFs are then aligned against the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) using BLAST to identify ARG-like sequences, typically with thresholds of ≥80% identity and ≥70% query coverage [2] [1].

- Abundance Normalization: To enable cross-study comparisons, ARG abundance is normalized. A common method is to calculate the copies per bacterial cell by normalizing ARG read counts to the number of 16S rRNA gene copies in the metagenome [2] [1].

- Mobile Genetic Element (MGE) Analysis: Tools like PlasmidFinder and INTEGRALL are used to identify MGEs in the same contigs as ARGs, helping to assess horizontal transfer potential [2].

Complementary Techniques

While metagenomics identifies all potential ARGs, other methods provide complementary data. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is used for high-sensitivity, absolute quantification of specific, pre-identified ARGs and is often employed to validate metagenomic findings or for routine monitoring [6] [5]. Culture-based methods isolate specific bacterial strains (e.g., Acinetobacter baumannii or Escherichia coli) from complex samples. Subsequent antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) and PCR amplification of ARGs from these isolates link resistance phenotypes to genotypes and identify pathogens of clinical concern [7].

Success in resistome research relies on a suite of established reagents, databases, and analytical tools.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for ARG Profiling

| Category | Item | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) | Standardized DNA extraction from complex environmental samples. |

| Illumina DNA Prep Kit | Library preparation for shotgun metagenomic sequencing. | |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Enables quantitative PCR for targeted ARG detection and validation. | |

| Mueller-Hinton Agar | Medium for culturing bacterial isolates and performing AST. | |

| Bioinformatic Databases | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | Central repository for ARG sequences and associated metadata for annotation. |

| INTEGRALL Database | Specialized database for identifying integrons and gene cassettes. | |

| PlasmidFinder | Tool for identifying plasmid replicons in sequence data. | |

| Analytical Tools & Algorithms | MetaPhlAn3 | Profiling microbial community composition from metagenomic data. |

| Prodigal | Predicting protein-coding genes (ORFs) in metagenomic assemblies. | |

| Random Forest Algorithm | Machine learning for identifying key ARG indicators and classifying samples. |

Discussion and Comparative Analysis

The data reveals a clear gradient of ARG abundance and diversity, closely tied to anthropogenic activity. WWTPs and livestock farms represent anthropogenically enriched reservoirs with high abundance and diversity of ARGs, including those conferring resistance to critically important antibiotics like carbapenems [1] [8]. The strong correlation between ARG composition and bacterial taxonomy in these environments suggests that community structure is a key driver of the resistome [1]. Furthermore, the high prevalence of MGEs and their significant co-occurrence with ARGs in polluted samples underscore the enhanced potential for horizontal gene transfer [4] [9].

In contrast, natural environments like Arctic soils maintain a native resistome with low abundance and diversity, featuring genes distinct from those found in clinical settings [4]. However, even low-anthropogenic impact environments are not devoid of risk. Studies of urban coastal waters show that diverse human activities (industrial, recreational) can select for distinct pathogenic bacteria and ARG profiles, with network analysis revealing complex associations between microbes and ARGs [5]. A critical finding from comparative farming studies is that ARGs persist in 97% of antibiotic-free farms, indicating that once resistance is established, merely removing antibiotic pressure is insufficient for its eradication [3]. This points to the role of environmental contamination, co-selection from heavy metals, and stable maintenance of resistance genes in bacterial communities as perpetuating factors.

This comparative analysis underscores that mitigating the spread of antibiotic resistance requires a One Health approach that integrates surveillance and intervention across human, animal, and environmental reservoirs. Future research should prioritize tracking the flow of core ARGs and their mobile vectors between these interconnected realms to develop effective containment strategies.

Continental and Habitat-Specific Variations in ARG Composition

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) represent one of the most pressing challenges to global public health in the 21st century. Understanding their distribution patterns across different geographical scales and habitat types is fundamental to evaluating health risks and developing effective mitigation strategies. This comparison guide provides a systematic analysis of ARG composition variations across continents and habitats, synthesizing experimental data from recent global-scale studies. The objective assessment of these distribution patterns provides critical insights for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working within the One Health framework, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health.

Continental Scale Variations in ARG Composition

Global Distribution Patterns in Wastewater Treatment Plants

A comprehensive global analysis of 226 activated sludge samples from 142 wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) across six continents revealed distinct continental signatures in ARG profiles [1].

Table 1: Continental Variations in ARG Abundance and Diversity in WWTPs

| Continent | Total ARG Abundance | ARG Richness | Shannon's H Index | Distinct Compositional Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | Similar to other continents | Significantly higher | Significantly higher | Distinct from other continents |

| Africa | Similar to other continents | High (similar to Asia) | High | Distinct from other continents |

| Europe | Similar to other continents | Moderate | Moderate | Distinct from other continents |

| North America | Similar to other continents | Moderate | Moderate | Distinct from other continents |

| South America | Similar to other continents | Moderate | Moderate | Distinct from other continents |

| Australia | Similar to other continents | Moderate | Moderate | Distinct from other continents |

Despite similar overall abundance across continents, the richness and diversity of ARGs showed significant geographical patterning. Asian WWTPs exhibited significantly higher mean ARG richness compared to other continents except Africa, suggesting greater diversity of resistance determinants in these regions [1]. At the national level, countries exhibited variations in total ARG abundance, with Chile and Canada showing the lowest levels, while Switzerland and Colombia demonstrated the highest abundances [1].

The core resistome of global WWTPs consisted of 20 ARGs that were present in all samples analyzed, accounting for 83.8% of the total ARG abundance [1]. The most abundant genes conferred resistance to major antibiotic classes:

- TetracyclineResistanceMFSEffluxPump (15.2%)

- ClassB β-lactam resistance (13.5%)

- vanT gene in vanG cluster (glycopeptide resistance, 11.4%)

When aggregated by resistance mechanism, ARGs encoding antibiotic inactivation dominated (55.7%), followed by target alteration (25.9%) and efflux pumps (15.8%) [1].

Temporal Trends in Soil Resistomes

Global analysis of soil resistomes has revealed increasing temporal trends in ARG risk. Analysis of 2,540 soil samples with collection dates spanning 2008 to 2021 showed that while total ARG abundance remained time-independent, the relative abundance of high-risk "Rank I ARGs" and their occurrence frequency significantly increased over time [10]. Rank I ARGs are classified based on host pathogenicity, gene mobility, and enrichment in human-associated environments, representing the greatest potential health concern.

The connectivity between soil and human resistomes has also intensified over time, with soil ARGs showing higher genetic overlap with clinical Escherichia coli genomes (1985-2023), suggesting an increasing linkage between environmental and clinical resistance pools [10].

Habitat-Specific Variations in ARG Composition

Comparative Resistome Profiles Across Ecosystems

Table 2: ARG Composition Across Different Habitat Types

| Habitat Type | Dominant ARG Classes | Relative Abundance | Key Carriers/Hosts | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater Treatment Plants | β-lactam (46.5%), Glycopeptide (24.5%), Tetracycline (16.2%) | High (core 20 ARGs present in all WWTPs) | Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria | Strong correlation with mobile genetic elements |

| Human Gut | Not specified in results | Distinct from AS resistomes | Human gut microbiota | Compositionally distinct from environmental resistomes |

| Soil | Multidrug efflux pumps | Lower than livestock and human feces | Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria | Rank I ARGs increasing over time |

| Ocean/Marine | Not specified in results | Distinct from AS resistomes | Marine microbial communities | Compositionally distinct from terrestrial resistomes |

| Rivers & Lakes (China) | Sulfonamide, Tetracycline | 10⁷-10¹¹ copies/L (surface waters) | Aquatic bacteria | Higher in eastern/southern China |

| Mangrove Ecosystems | Tetracycline, Sulfonamide, β-lactam, Multidrug | 10²-10⁶ copies/g (sediment) | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | Elevated near aquaculture/urban areas |

Principal coordinate analysis demonstrates that WWTP resistomes are compositionally distinct from human gut and ocean resistomes but show similarity to sewage and soil resistomes [1]. This pattern persists whether ARGs are analyzed at the individual gene level or aggregated by drug class [1].

The similarity between WWTP, sewage, and soil resistomes likely reflects their interconnection through wastewater flows and stormwater runoff [1]. Soil shares approximately 60.1% of its total ARGs and 50.9% of its Rank I ARGs with other habitats, with human feces (75.4%), chicken feces (68.3%), WWTP effluent (59.1%), and swine feces (53.9%) being the largest contributors to soil Rank I ARGs [10].

Niche-Specific Distribution in Urban Sewer Systems

Urban sewer systems exhibit distinct vertical stratification of ARGs, with different distribution patterns in sediments, sewage, and aerosols [9]. Aminoglycoside, beta-lactamase, and multidrug resistance genes represent the predominant types across all sewer compartments, but their relative abundances and associated bacterial hosts vary significantly [9].

In sewer sediments, which typically contain high biomass, Bacteroides, Arcobacter, and Aeromonas are the predominant genera hosting ARGs [9]. Mobile genetic elements play a crucial role in ARG transfer among microorganisms across all sewer compartments, but environmental drivers differ:

- Sediments and sewage: Significantly influenced by basic properties (λ = 0.32), heavy metals (λ = 0.27), and antibiotics (λ = 0.12)

- Aerosols: Primarily driven by bacterial composition (λ = 0.59) and α-diversity (λ = 0.46)

Although sediments and sewage carry higher risk burdens of typical ARGs, aerosolized ARGs pose direct inhalation exposure risks that warrant greater attention in future risk assessments [9].

Experimental Methodologies for Global ARG Profiling

Standardized Metagenomic Sequencing Pipeline

The Global Water Microbiome Consortium (GWMC) established a systematic global campaign for collection, sequencing, and analysis of activated sludge samples using identical protocols to ensure comparability across continents [1].

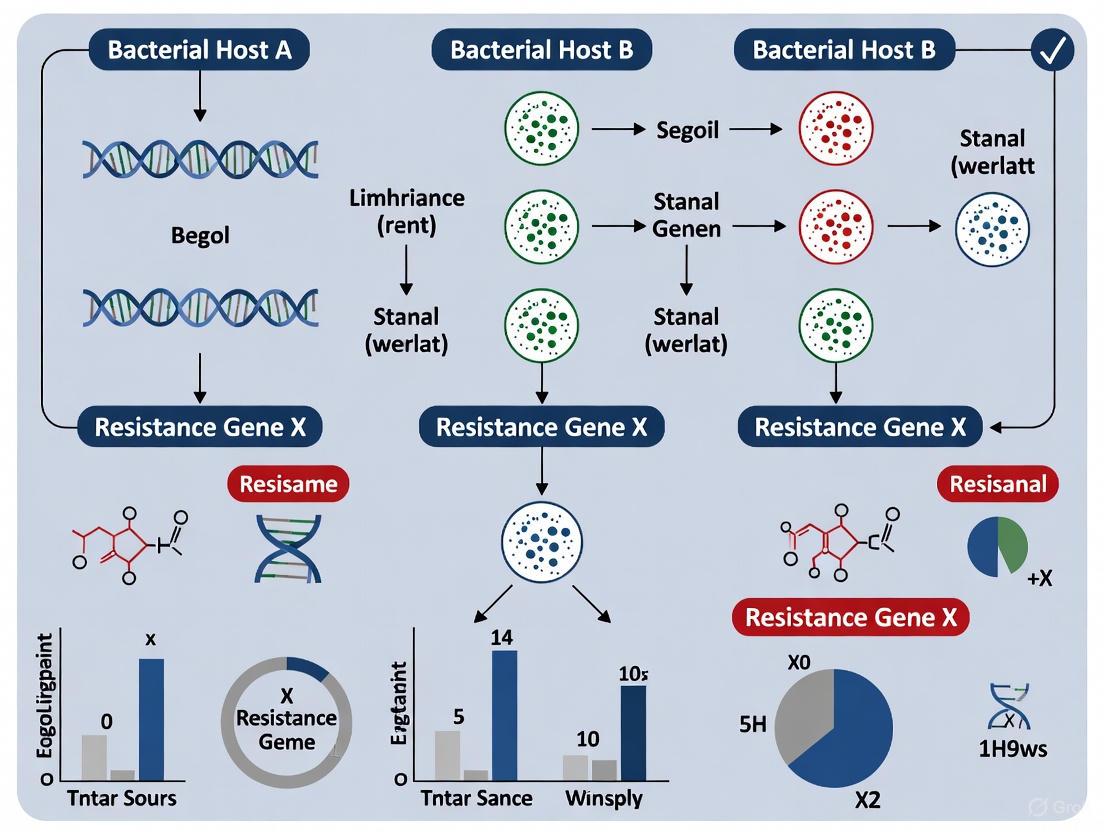

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for global ARG profiling in wastewater treatment plants.

Quantitative ARG Detection and Analysis

Sample Collection and Processing: For the global WWTP study, 226 activated sludge samples were collected from 142 wastewater treatment plants across six continents [1]. Samples were immediately preserved after collection and processed using standardized DNA extraction protocols to minimize technical variability [1].

Sequencing and Assembly: A total of 2.8 terabases of sequence data was generated with an average of 12.3 ± 3.9 Gb per sample [1]. Quality-filtered metagenomic reads were assembled into 36,147,212 contigs longer than 1 kb, from which 34,860,381 non-redundant open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted [1].

ARG Annotation and Quantification: ORFs were annotated as ARG sequences using standardized databases and criteria [1]. A total of 37,029 (0.11%) ORFs were identified as ARGs, representing 179 different ARGs relevant to 15 drug classes [1]. ARG abundance was normalized to copy number per bacterial cell to enable cross-comparison between samples [1].

Statistical Analysis: Rarefaction analysis confirmed sufficient sequencing depth to capture ARG diversity [1]. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was used to identify significant differences in resistome composition across continents, followed by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) for visualization [1]. Procrustes analysis revealed strong associations between bacterial community structure and resistome composition [1].

Research Reagent Solutions for ARG Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ARG Monitoring

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples from Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic Sequencing Kits | Comprehensive profiling of ARGs and microbial communities | Shotgun sequencing of 226 AS samples [1] |

| PCR/qPCR Assays | Targeted quantification of specific ARGs | Detection of blá₁ₘₚ₋₁, mecA, blaNDM-1 [11] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality DNA extraction from complex matrices | Standardized protocol for global WWTP samples [1] |

| Mobile Genetic Element Markers | Tracking horizontal gene transfer potential | Detection of plasmids, transposons, integrons [9] |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Reagents | Bacterial community profiling | Analysis of microbial community structure [1] |

| ARG-Specific Databases | Annotation and classification of resistance genes | SARG3.0_S database for similarity search [10] |

The continental and habitat-specific variations in ARG composition highlighted in this comparison guide demonstrate the complex biogeography of antibiotic resistance. The distinct continental signatures in WWTP resistomes, coupled with the unique ARG profiles characteristic of different habitats, underscore the importance of context-specific approaches to monitoring and mitigating antibiotic resistance. The experimental data presented reveals that while a core set of ARGs is ubiquitous across global WWTPs, significant variations in richness, diversity, and compositional structure exist across geographical scales and ecosystem types. The increasing connectivity between environmental and human resistomes, particularly for high-risk Rank I ARGs, highlights the importance of integrated surveillance strategies that span clinical, agricultural, and environmental compartments. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings emphasize the need to consider geographical origin and habitat type when assessing resistance risks and designing intervention strategies.

The rapid global spread of antibiotic resistance represents one of the most pressing public health challenges of our time, with antibiotic-resistant infections directly causing an estimated 1.27 million deaths annually [12]. Understanding the distribution and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) requires identifying the primary bacterial hosts that serve as reservoirs in different environments. This comparison guide objectively analyzes two critical reservoirs: Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs), where Chloroflexi and other specific phyla dominate as ARG carriers, and livestock settings, where Proteobacteria represent a major resistance reservoir. By comparing the methodologies, findings, and implications of research in these distinct environments, this guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured analysis of ARG host distribution patterns and the experimental approaches used to identify them.

Table 1: Key Environmental Reservoirs of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

| Environment | Primary Bacterial Hosts | Dominant ARG Classes | Research Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) | Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria | Beta-lactam, Glycopeptide, Tetracycline | Global (142 WWTPs across 6 continents) [1] |

| Livestock Settings | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | Tetracycline, Sulfonamide, Beta-lactam | Global (96 countries) [13] |

| Aquaculture Sediments | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidota | Sulfonamide, Tetracycline, Quinolone | Regional (China) [14] |

| Marine Environments | Proteobacteria | Sulfonamide, Beta-lactam | Global (Multiple oceans and seas) [15] |

Comparative Analysis of Primary Bacterial Hosts Across Environments

Chloroflexi as Key ARG Hosts in Wastewater Treatment Plants

Activated sludge from wastewater treatment plants represents a significant reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes, with recent global analysis revealing consistent patterns of ARG distribution. A comprehensive study analyzing 226 activated sludge samples from 142 WWTPs across six continents identified a core set of 20 ARGs present in all facilities, accounting for 83.8% of the total ARG abundance [1]. The most abundant ARGs confer resistance to tetracycline (15.2%), beta-lactams (13.5%), and glycopeptides (11.4%) through mechanisms including antibiotic inactivation (55.7%), target alteration (25.9%), and efflux pumps (15.8%) [1].

Metagenome analysis has consistently identified Chloroflexi as one of the major bacterial phyla carrying ARGs in WWTPs, alongside Acidobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria [1]. These filamentous bacteria are not merely structural components of activated sludge flocs but play a significant functional role in ARG maintenance and potential dissemination. Members of the Caldilineae class within Chloroflexi are particularly abundant, comprising 12-19% of the Chloroflexi population in municipal WWTPs [16]. The strong association between bacterial community structure and resistomes (Procrustes analysis: M² = 0.74, p < 0.001) underscores the importance of these specific bacterial hosts in shaping the ARG profiles of WWTPs [1].

Proteobacteria Dominance in Livestock and Related Environments

In contrast to WWTP environments, livestock settings show a clear dominance of Proteobacteria as carriers of antibiotic resistance genes. Analysis of ARG distribution across livestock wastes (including swine, poultry, and cattle operations) reveals that Proteobacteria represent the most abundant phylum harboring ARGs, followed by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes [13]. This pattern extends beyond livestock facilities to adjacent environments, including aquaculture sediments where Proteobacteria dominate the microbial community and show strong correlations with ARG abundance [14].

The abundance of ARGs in livestock waste significantly exceeds levels found in other environments, with swine and chicken waste containing three to five orders of magnitude more ARGs than hospital and municipal wastewaters [13]. Tetracycline and sulfonamide resistance genes are particularly prevalent in livestock settings, reflecting the extensive use of these antibiotic classes in animal husbandry. Globally, livestock waste shows substantial variation in ARG abundance, with China reporting the highest levels according to available data [13].

Table 2: Dominant Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Different Environments

| Environment | Most Abundant ARGs | Relative Abundance | Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater Treatment Plants | TetracyclineMFSEfflux_Pump | 15.2% | Efflux pump [1] |

| Wastewater Treatment Plants | ClassB | 13.5% | Antibiotic inactivation [1] |

| Wastewater Treatment Plants | vanT (vanG cluster) | 11.4% | Target alteration [1] |

| Livestock Waste | tet genes | Varies by country | Ribosomal protection [13] |

| Livestock Waste | sul genes | Varies by country | Target alteration [13] |

| Aquaculture Sediments | sul1, tetW | Highest abundance | Various [14] |

| Marine Environments | sul1 | Ubiquitous | Target alteration [15] |

Methodologies for Identifying ARG Hosts: Experimental Protocols

Global WWTP Sampling and Metagenomic Analysis Protocol

The identification of Chloroflexi as primary ARG hosts in WWTPs emerged from a standardized global sampling and analysis protocol implemented by the Global Water Microbiome Consortium [1]. The methodology can be summarized as follows:

Sample Collection: 226 activated sludge samples were collected from 142 WWTPs across six continents using identical protocols to ensure comparability.

DNA Sequencing: Community DNA was sequenced via shotgun metagenomics, generating 2.8 terabases of data (average 12.3 ± 3.9 Gb per sample). Sequencing depth was validated through rarefaction analysis of both 16S rRNA genes and ARGs [1].

Bioinformatic Processing:

- Assembly of 36,147,212 contigs >1 kb from filtered metagenomic reads

- Prediction of 34,860,381 non-redundant open reading frames (ORFs)

- Annotation of 37,029 (0.11%) ORFs as ARG sequences

- Identification of 179 different ARGs conferring resistance to 15 drug classes

Host Identification: ARG hosts were determined through metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) and analysis of ARG co-occurrence with bacterial taxonomic markers, revealing Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria as major carriers [1].

Livestock ARG Host Identification Approach

Research identifying Proteobacteria as dominant ARG hosts in livestock environments employs complementary but distinct methodological approaches:

Sample Collection: Analysis of livestock wastes (manure, wastewater) from different farm types (swine, poultry, cattle) and geographical locations.

ARG Quantification: Utilization of both quantitative PCR (for specific ARGs) and high-throughput sequencing methods to determine absolute abundance (copies/g or copies/mL) and relative abundance (copies/16S rRNA) [13].

Host Tracking: Correlation-based network analysis to identify associations between ARGs and specific bacterial taxa, consistently revealing Proteobacteria as key hosts in livestock settings [14]. This approach has demonstrated co-occurrence patterns between ARGs (sul1, sul2, blaCMY, blaOXA, qnrS, tetW, tetQ, tetM) and bacterial taxa from Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes [14].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for identifying bacterial hosts of antibiotic resistance genes, integrating metagenomic sequencing and bioinformatic analysis.

Inter-Environment Transmission and One Health Implications

Horizontal Transfer of ARGs Between Bacterial Hosts

The transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between diverse bacterial hosts represents a critical mechanism in the dissemination of resistance across environments. Systematic analysis of nearly 1 million ARGs from over 400,000 bacterial genomes has identified 661 inter-phylum transfer (IPT) events, demonstrating that ARGs regularly move between evolutionarily distant hosts [17]. The frequency of IPT varies substantially between ARG classes, with tetracycline ribosomal protection genes showing the highest number of transfers (106), followed by aminoglycoside acetyltransferase AAC(6′) (81) and class A beta-lactamases (75) [17].

Notably, mobile genetic elements (MGEs) play a crucial role in facilitating ARG transfer between hosts. In WWTPs, 57% of 1,112 recovered high-quality genomes possessed putatively mobile ARGs, with ARG abundance positively correlating with the presence of MGEs [1]. Similarly, studies in aquaculture sediments found significant correlations between ARGs and class 1 integrons (intl1), suggesting MGEs mediate horizontal transfer [14]. This cross-phylum transfer capability enables ARGs to move between the Chloroflexi-dominated reservoirs in WWTPs and Proteobacteria-dominated reservoirs in livestock settings, creating interconnected resistance networks.

One Health Perspectives on ARG Transmission

The transmission of ARGs follows complex pathways that interconnect human, animal, and environmental reservoirs through what has been termed the "One Health" continuum. Livestock farming systems represent a major source of ARG transmission, driven by global antimicrobial usage that exceeds 200,000 tons annually, with approximately 73% of all antimicrobials used in animal production [12].

Key transmission pathways include:

- Direct Contact: Farmers, veterinarians, and abattoir workers exposed to livestock-associated ARBs

- Food Chain: Consumption of contaminated meat, dairy, and aquaculture products

- Environmental Spread: Application of manure to agricultural lands, runoff into water systems, and aerosol dissemination [12]

Research at the wildlife-livestock interface has revealed that feral swine and coyotes harbor more abundant antibiotic-resistant microorganisms compared to grazing cattle, suggesting wildlife could serve as vectors for ARG dissemination between human-dominated and natural environments [18]. These findings underscore the interconnectedness of resistance reservoirs and the importance of cross-disciplinary approaches to mitigating ARG spread.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ARG Host Identification Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in ARG Host Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | TIANamp Soil DNA Kit [14] | High-quality metagenomic DNA extraction from complex environmental samples |

| PCR Reagents | SmartChip qPCR reagents [19] | High-throughput quantification of specific ARG targets |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina Shotgun Sequencing [1], 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing [20] | Comprehensive profiling of microbial communities and resistance genes |

| Bioinformatic Tools | fARGene [17], SILVA database [20] | Accurate identification of ARGs and taxonomic classification |

| Clustering Algorithms | PERMANOVA, ANOSIM [20] | Statistical analysis of microbial community patterns and ARG distribution |

| Network Analysis | Co-occurrence network analysis [14] | Identification of potential ARG-host relationships and transfer pathways |

This comparison guide has systematically identified the distinct primary bacterial hosts of antibiotic resistance genes in two critical environments: Chloroflexi in wastewater treatment plants and Proteobacteria in livestock settings. These patterns reflect both environmental selection pressures and the ecological characteristics of these bacterial phyla in different habitats.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight several critical considerations:

- Environment-Specific Interventions: Mitigation strategies must account for the distinct host profiles in different settings, targeting the predominant bacterial carriers in each environment.

- Transfer Monitoring: The demonstrated ability of ARGs to transfer between phyla underscores the importance of monitoring cross-environmental transmission.

- Methodological Standardization: The consistent identification of these patterns across studies employing standardized protocols supports continued method harmonization in ARG research.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the mechanisms that enable certain bacterial taxa to serve as particularly successful ARG reservoirs, developing interventions that disrupt ARG transfer between hosts, and expanding global monitoring efforts to track the evolution of these host-ARG relationships over time. As antibiotic resistance continues to pose significant threats to global health, understanding these fundamental patterns of ARG distribution across bacterial hosts remains essential for developing effective countermeasures.

The Role of Mobile Genetic Elements in Shaping Resistome Structures

Antibiotic resistance represents a paramount global health challenge, primarily driven by the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). The collection of all ARGs within a given environment, known as the resistome, is dynamically shaped by the activity of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) [21]. These elements facilitate the horizontal transfer of resistance genes between bacteria, accelerating the development of multidrug-resistant pathogens. Understanding the mechanisms by which MGEs influence resistome structures is critical for devising strategies to combat antibiotic resistance. This review synthesizes current knowledge on major MGE types, their distribution across One-Health sectors (human, animal, environment), and the experimental methodologies enabling their study, providing a comparative guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mobile Genetic Elements: Types and Mechanisms

MGEs are DNA sequences capable of moving within or between DNA molecules, and between bacterial cells [22]. They act as primary vectors for the horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of ARGs. The table below summarizes the key MGE types and their characteristics.

Table 1: Major Types of Mobile Genetic Elements Involved in Antibiotic Resistance

| MGE Type | Key Characteristics | Primary Role in AMR | Example Elements & Carried ARGs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insertion Sequences (IS) | Small (<3 kb), encode transposase, terminal inverted repeats (IR) [22] [23]. | Intracellular movement; can form composite transposons; provide promoters for ARG expression [22]. | ISAba1 upstream of blaOXA-51-like in Acinetobacter baumannii (carbapenem resistance) [22]. |

| Transposons (Tn) | Larger than IS, carry additional passenger genes (e.g., ARGs) [23]. | Direct mobilization of ARGs within a cell [22]. | Tn9 (catA1 - chloramphenicol resistance) [22]. Tn1999 (blaOXA-48-like - carbapenem resistance) [22]. |

| Integrons | Site-specific recombination system; contain intI gene, attI site, and promoter Pc [22] [23]. | Capture and coordinate expression of gene cassettes, often containing ARGs [22]. | Multiple drug resistance integrons in Gram-negative pathogens. |

| Plasmids | Self-replicating, circular DNA; often conjugative [23]. | Intercellular transfer of ARGs via conjugation; major vehicles for multi-resistance [23] [24]. | Plasmids carrying bla genes (β-lactamase), erm genes (macrolide resistance) [23]. |

| Integrative Conjugative Elements (ICEs) | Integrate into and excise from chromosome; transfer via conjugation [22]. | Large-scale transfer of genomic islands containing ARGs [22]. | ICEs carrying van genes (vancomycin resistance) in Enterococci [22]. |

The following diagram illustrates the basic structures of these key MGEs and their functional components.

Comparative Resistome Structures Across One-Health Sectors

The distribution and abundance of ARGs, facilitated by MGEs, vary significantly across the human, animal, and environmental sectors of the One-Health paradigm [21]. The following table provides a quantitative comparison of resistome profiles.

Table 2: Comparative Resistome Profiles Across One-Health Sectors

| Sector / Environment | Key Findings on ARG & MGE Abundance/Diversity | Notable ARGs & Associated MGEs | Dominant Bacterial Hosts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gut | High relative abundance of ARGs but lower taxonomic and MGE diversity compared to external environments [8]. | Multidrug resistance genes; genes on plasmids and transposons [8]. | Limited taxonomic diversity; commensals and opportunistic pathogens. |

| Animal Gut (e.g., Poultry, Rodents) | Varies with production system. Conventional (CO) systems show higher ARG/MGE abundance vs. organic (OR) [25]. Wild rodents harbor diverse ARGs (e.g., tet(Q), tet(W), vanG) [26]. | Conventional Chickens: Higher abundance of transposases (97.2% of MGEs) [25]. Rodents: E. coli carries highest ARG number (1540 ORFs) [26]. | Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Citrobacter braakii [26]. |

| Hospital Wastewater (HWW) | ARG hotspot. General Hospitals (GHs) show higher ARG abundance and risk than Non-General Hospitals (NGHs) [27]. Plasmid-mediated ARGs (45.21%) dominate [27]. | Aminoglycoside resistance genes enriched in GHs; bla genes (IND, GES, IMP) [27]. Co-occurrence with MGEs frequent [27]. | Potential pathogens like Rhodocyclaceae bacterium ICHIAU1, Acidovorax caeni [27]. |

| Natural Environments (Soil, Water) | High taxonomic diversity linked to high MGE and biocide/metal resistance gene diversity, but generally lower known ARG abundance [8]. | Intrinsic and proto-resistance genes; novel ARG contexts [21] [8]. | Highly diverse environmental bacteria. |

| Anthropogenically-Impacted Environments (Wastewater, Polluted Sites) | High ARG abundance and diversity, comparable to human gut [8]. Industrial antibiotic pollution creates extreme selection pressure [8]. | sul2, aph genes, qnr, beta-lactamase genes [8]. Often co-located with MGEs on plasmids [8]. | Wastewater microbiota; bacteria adapted to pollutant stress. |

The interconnectivity of these sectors, and the potential flow of MGEs and ARGs among them, is conceptualized within the One-Health framework below.

Key Experimental Methodologies for Resistome and Mobilome Analysis

Deciphering resistome structures and the role of MGEs relies on advanced genomic techniques. The following workflow outlines a standard metagenomic analysis protocol.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1. Metagenomic Sequencing and Assembly (as cited in [26] and [27]):

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Environmental (e.g., water, soil) or biological (e.g., gut contents) samples are collected. Total community DNA is extracted using commercial kits. For example, in the wild rodent study, 2198 bacterial isolates were cultured, and 610 metagenomic samples were processed [26].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: DNA libraries are prepared following standard Illumina protocols. Sequencing is performed on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq, generating high-throughput, short-read data. The hospital wastewater study generated a 280.28 Gbp dataset [27].

- Read Processing and Metagenomic Assembly: Raw sequencing reads are quality-controlled (using tools like Trimmomatic or FastQC) to remove adapters and low-quality bases. Cleaned reads are assembled into contigs using assemblers like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes [26] [27].

2. Gene Annotation and Binning:

- Gene Prediction and ARG Annotation: Open Reading Frames (ORFs) are predicted from contigs. Protein sequences are aligned against the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) using tools like BLASTP or RGI to identify ARGs [26] [8].

- MGE Annotation: Similarly, ORFs are searched against specialized MGE databases (e.g., a transposase database) to identify and classify MGEs, such as insertion sequences, transposases, and integrases [26].

- Metagenomic Binning: Contigs are grouped into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) based on sequence composition and abundance across samples using tools like CONCOCT, MetaBAT2, or MaxBin2. MAGs are checked for quality (completeness and contamination) using CheckM [26] [27]. This step is crucial for linking ARGs and MGEs to their specific bacterial hosts.

3. Data Analysis and Risk Assessment:

- Abundance and Diversity Profiling: The relative abundance of ARGs and MGEs is calculated by normalizing read counts (e.g., copies per 16S rRNA gene or per million reads). Diversity (richness) is measured as the number of unique ARG types per sample [8].

- Co-occurrence Network Analysis: Statistical methods (e.g., correlation analysis) are used to investigate the co-occurrence patterns between ARGs, MGEs, and bacterial taxa within samples, helping to infer potential gene transfer networks [27].

- Risk Assessment (ARRI): The Antibiotic Resistome Risk Index (ARRI) can be calculated by integrating data on ARG mobility potential (association with MGEs), pathogenicity of host bacteria, and clinical relevance of the ARGs [27].

Table 3: Key Reagents, Databases, and Tools for Resistome and Mobilome Research

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Sequencing Platforms | Sequencing Technology | High-throughput shotgun sequencing of metagenomic DNA from complex samples [8]. |

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) | Bioinformatics Database | Repository of ARGs and associated proteins for functional annotation of metagenomic sequences [26]. |

| ISfinder | Bioinformatics Database | Centralized database for insertion sequences, aiding in the identification and classification of IS elements [22] [23]. |

| MGE-specific Databases | Bioinformatics Database | Custom or public databases for annotating MGEs like transposases, integrases, and plasmids [26]. |

| MetaBAT2 / CONCOCT | Bioinformatics Software | Algorithms for binning assembled contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) [26]. |

| CheckM | Bioinformatics Software | Tool for assessing the quality (completeness and contamination) of assembled genomes and MAGs [26]. |

Mobile genetic elements are fundamental architects of resistome structures across all One-Health sectors. Their ability to facilitate horizontal gene transfer enables the rapid evolution and dissemination of antibiotic resistance, blurring the boundaries between environmental reservoirs, livestock, and human pathogens. Future research must continue to leverage cutting-edge metagenomics and computational tools to track the flow of MGEs at the interfaces of these sectors, identify critical ARG-MGE combinations, and elucidate the factors driving their selection and persistence. A deep understanding of these dynamics is paramount for developing targeted interventions, informing antibiotic stewardship policies, and mitigating the global threat of antimicrobial resistance.

From Sample to Insight: Methodologies for ARG Detection, Quantification, and Host Attribution

{#topic} Comparing Concentration and DNA Extraction Methods for Complex Matrices {#topic}

{#context} The accurate assessment of antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) distribution across different hosts and environmental reservoirs is a cornerstone of the "One Health" approach to combating antimicrobial resistance. This research is critically dependent on the initial steps of sample processing: concentration and DNA extraction. The methods chosen for these steps directly influence the observed ARG profile, microbial community composition, and the subsequent detection of low-abundance resistance determinants. This guide objectively compares common concentration and DNA extraction methodologies for complex matrices like wastewater and biological tissues, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their study designs in ARG surveillance [28] [29].

{## The Impact of Method Selection on ARG Analysis}

The primary challenge in analyzing complex matrices is the inherent trade-off between DNA yield, purity, and representativeness. Methodological choices can significantly bias results by selectively lysing certain cell types, co-extracting inhibitors, or failing to capture the full diversity of extracellular or intracellular DNA.

For instance, in national-scale wastewater surveillance, the choice between high-throughput quantitative PCR (HT qPCR) and metagenomic sequencing is often dictated by study goals, with the former offering higher sensitivity for specific, low-abundance ARGs and the latter providing a broader, untargeted view of the resistome [28]. This was evident in a comparative study of Welsh wastewater, where HT qPCR detected certain high-risk ARGs like blaNDM and blaVIM that were missed by metagenomic sequencing, while metagenomics revealed a much wider array of unique ARGs (491 in total) that were beyond the scope of the targeted qPCR chip [28]. Furthermore, the composition of the microbial community and ARG profiles varied significantly between hospital and treatment plant wastewater, and these differences were consistently captured by both methods, underscoring the influence of the sample matrix itself [28].

{## Comparison of Concentration and DNA Extraction Methods}

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics of common methods used for sample concentration and DNA extraction from complex matrices relevant to ARG research.

{#table1} Table 1: Comparison of Sample Concentration Methods for Liquid Matrices

| Method | Principle | Typical Recovery Efficiency | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Filtration [29] | Passage of sample through a microporous membrane to retain microorganisms. | Varies with membrane pore size and sample load; used for bacterial counts of 10⁵–10⁹ CFU/mL [29]. | Simple, cost-effective, allows for direct culture of retained biomass. | Prone to membrane clogging with turbid samples; may not efficiently recover viral particles or free DNA. | Clear water samples with moderate microbial load. |

| Ultracentrifugation | High-speed centrifugation to pellet microorganisms and particles. | High for particulate-associated ARGs. | Effective for concentrating diverse particle sizes, including viruses. | Requires specialized, expensive equipment; time-consuming; not easily scalable for large volumes. | Concentrating a broad spectrum of targets from various liquid matrices. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) [30] | Adsorption of nucleic acids or cells to a solid phase under specific conditions, followed by elution. | N/A (Primarily for purification) | Effective for purifying DNA from complex inhibitors; high purity yields. | Can be complex; requires optimization of pH and solvents; may involve multiple steps [30]. | Purifying DNA from complex biological extracts (e.g., tissue homogenates). |

{#table2} Table 2: Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods from Complex Solid Matrices

| Method | Principle | Key Performance Data | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonic Extraction [30] | Uses ultrasonic energy to disrupt cell walls and membranes. | Recovery rates: 64%–121% for 15 antibiotics in shellfish; LOD: 0.004–0.5 ng/g (dry weight) [30]. | Rapid, simple operation, effective for hard-to-lyse tissues. | May require subsequent purification (e.g., SPE); potential for DNA shearing with prolonged exposure. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Purification [30] | Purification of crude DNA extract using selective binding and elution from a sorbent. | Oasis PRiME HLB showed superior cleanup vs. Oasis HLB; no activation needed [30]. | High purity; removes PCR inhibitors like humic acids; can be automated. | Additional cost and processing time; recovery depends on sorbent and protocol. |

| Commercial Kit (Silica-column based) [28] [29] | Lysis with chaotropic salts, followed by binding of DNA to silica membrane and washing. | Widely used in wastewater metagenomic studies for consistency [28]. | High-quality, inhibitor-free DNA; standardized, reproducible protocols. | Cost per sample can be high; may have lower efficiency for Gram-positive bacteria. |

{## Detailed Experimental Protocols}

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed protocols for two methods highlighted in the search results, adapted for ARG analysis.

{### Protocol 1: Ultrasonic Extraction and SPE Purification from Biological Tissue [30]}

This protocol is designed for challenging biological matrices like shellfish软组织, which are rich in inhibitors.

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the freeze-dried tissue and weigh 0.2 g of the powder into a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

- Spiking and Equilibration: Add a suitable internal standard (e.g., isotope-labeled antibiotics), vortex to mix, and let it equilibrate in a fume hood overnight.

- Ultrasonic Extraction:

- Add 8 mL of extraction solvent (e.g., 80% acetonitrile or 80% methanol).

- Vortex for 1 minute to ensure thorough mixing.

- Sonicate the mixture for 15 minutes at 42 kHz.

- Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes and transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- Repeat the extraction step once and combine the supernatants (~16 mL total).

- Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cleanup:

- For Oasis PRiME HLB: Pass 10 mL of the combined extract directly through the SPE cartridge without prior conditioning. Collect the eluate, as target analytes pass through while impurities are retained.

- For Oasis HLB: Condition the cartridge with 5 mL methanol and 5 mL distilled water. Dilute the extract in 400 mL distilled water, add 0.2 g Na₄EDTA, and adjust the pH. Load the sample, wash with 10 mL water, dry the cartridge under vacuum for ~1 hour, and elute targets with 10 mL methanol.

- Concentration and Analysis: Evaporate the eluate to near dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream at 35°C. Reconstitute the residue in 1 mL of initial mobile phase (e.g., acetonitrile:water, 1:1 v/v), filter through a 0.22 μm membrane, and analyze via UPLC-MS/MS or PCR.

{### Protocol 2: Integrated Workflow for ARG Analysis from Water [29]}

This protocol combines culture-based and culture-independent (metagenomic) techniques for a comprehensive analysis.

- Sample Collection and Concentration:

- Collect water samples in sterile containers and filter through sterile cheesecloth to remove large particulates.

- Concentrate microorganisms via membrane filtration onto 0.22 μm filters or by centrifugation.

- Total and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacterial Counts:

- Plate appropriate dilutions of the concentrated sample onto general media (e.g., R2A agar) and onto the same media supplemented with specific antibiotics (e.g., 3 μg/mL cefotaxime, 0.5 μg/mL ciprofloxacin).

- Incubate plates at 35–37°C for 48 hours.

- Calculate colony-forming units (CFU) per mL for both total and antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

- DNA Extraction for Metagenomics:

- Extract total genomic DNA directly from the concentrated biomass or filters using a commercial silica-column-based kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- This DNA represents the entire microbial community, including unculturable organisms.

- Downstream Analysis:

{## Workflow Visualization}

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting the appropriate methodology based on research objectives and sample type.

{#graphviz}

{## The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials}

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for successfully executing the concentration and DNA extraction protocols for ARG analysis.

{#table3} Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for ARG Analysis from Complex Matrices

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Oasis PRiME HLB SPE Cartridge [30] | A reverse-phase sorbent for purifying extracts; requires no conditioning and removes phospholipids and other matrix interferents. | Cleanup of ultrasonic extracts from shellfish tissue prior to UPLC-MS/MS analysis [30]. |

| R2A Agar [29] | A low-nutrient culture medium designed to support the growth of stressed and environmental microorganisms, including those from water systems. | Culturing and enumerating heterotrophic bacteria and antibiotic-resistant isolates from water samples [29]. |

| Na₄EDTA [30] | A chelating agent that binds metal ions, preventing them from interfering with the analysis of certain antibiotic classes. | Added to extraction buffers to improve the recovery and stability of antibiotics like tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones [30]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Isotope-labeled antibiotics) [30] | Compounds with nearly identical chemical behavior to the analytes of interest, used to correct for losses during sample preparation and matrix effects during analysis. | Added to samples before extraction to quantify antibiotic concentrations via mass spectrometry [30]. |

| 0.22 μm Nylon Filters | For sterile filtration of samples to remove particulate matter and for sterilizing solutions and buffers. | Initial filtration of water samples and final filtration of DNA extracts before instrumental analysis [30] [29]. |

{## Conclusion}

The selection of concentration and DNA extraction methods is a critical determinant in the successful evaluation of antibiotic resistance gene distribution. No single method is universally superior; the optimal choice is a deliberate compromise dictated by the sample matrix, the specific ARG targets, and the analytical endpoint (e.g., qPCR vs. metagenomics). For targeted, sensitive detection of specific ARGs in inhibitor-rich matrices like animal tissues, a robust method combining ultrasonic extraction with SPE purification is highly effective [30]. Conversely, for broad-spectrum resistome discovery in wastewater, sample concentration followed by commercial kit DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing provides the most comprehensive picture [28] [29]. Researchers must clearly report their chosen methodologies to enable valid cross-study comparisons and advance our collective understanding of ARG dynamics within the "One Health" framework.

The precise quantification of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) is fundamental to understanding their distribution, abundance, and transmission across different hosts and environments, from the human gut to agricultural settings and wastewater systems. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) are two cornerstone technologies for this task. While both amplify target nucleic acids with high specificity, their underlying principles and performance characteristics differ significantly. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of qPCR and ddPCR to help researchers select the optimal method for the absolute quantification of ARGs in complex samples, a critical need in the era of growing antimicrobial resistance [31].

The core difference between qPCR and ddPCR lies in how the PCR reaction is processed and quantified.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR): This method amplifies target DNA in a bulk reaction. Fluorescence is measured in real-time during the exponential phase of amplification, and the cycle threshold (Ct) at which the signal crosses a predefined level is used for quantification. This Ct value is compared to a standard curve to determine the starting concentration, resulting in a relative quantification that is dependent on the calibration standards [32] [33] [31].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): This technique partitions a single PCR reaction into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, creating individual microreactors. Amplification occurs within each droplet, which is then read at the endpoint and scored as positive or negative based on fluorescence. The absolute concentration of the target molecule is then calculated directly using Poisson statistics, without the need for a standard curve [34] [32] [31].

The workflow for both technologies, from sample preparation to data analysis, is summarized below.

Head-to-Head Performance Comparison

The choice between qPCR and ddPCR has profound implications for the sensitivity, precision, and robustness of ARG quantification, especially in challenging, inhibitor-prone environmental samples.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for qPCR and ddPCR based on experimental data from various studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of qPCR and ddPCR for Nucleic Acid Quantification

| Performance Parameter | qPCR | ddPCR | Experimental Context & Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) [32] [31] | Absolute (no standard curve) [32] [31] | ddPCR provides a direct count of target molecules [31]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Higher LOD [33] | 10-fold lower LOD than qPCR in some studies [33] | Enables detection of rare targets and low-abundance ARGs [34] [31]. |

| Precision & Reproducibility | Good for high-abundance targets [35] | Superior precision for low-abundance targets (Cq ≥ 29) [35] | A 2017 study found ddPCR produced more precise and reproducible data with low-level targets [35]. |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Susceptible; inhibitors affect amplification efficiency and Ct values [34] [36] | High tolerance; partitioning minimizes inhibitor impact [34] [32] | In environmental samples with inhibitors, ddPCR maintained precise quantification where qPCR faltered [34] [35]. |

| Dynamic Range | Broad dynamic range [32] [36] | Can saturate at high target concentrations (>106 copies/µL) [33] | qPCR is suitable for wider concentration ranges, while ddPCR excels at low copy numbers [32]. |

| Ability to Detect Small Fold-Changes | Lower precision for small differences [32] | High precision; can detect fold-changes as low as 10% [32] | Critical for accurately measuring subtle shifts in ARG abundance in response to environmental pressures. |

Application in ARG and Complex Environmental Samples

The theoretical advantages of ddPCR are borne out in practical applications involving complex samples. A 2025 study on ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB)—a functionally important group in nitrogen cycling—directly compared the technologies on samples from wastewater treatment plants and environmental water. The study found that ddPCR "produced precise, reproducible, and statistically significant results in all samples," particularly outperforming qPCR in complex samples characterized by low target levels and high backgrounds of non-target DNA and PCR inhibitors [34]. This robustness is attributed to the partitioning step, which dilutes inhibitors across thousands of droplets, making the amplification in individual droplets less susceptible to interference [34] [35]. Furthermore, ddPCR's superior sensitivity makes it the preferred tool for detecting rare targets and minute (≤2-fold) changes in expression, which are often critical in gene expression studies and monitoring the emergence of low-abundance ARGs [35].

Experimental Protocols for ARG Quantification

To ensure reproducible and high-quality results, adherence to validated experimental protocols is essential. The following methodologies are adapted from cited comparative studies.

Sample Collection, DNA Extraction, and Quality Control

- Sampling and Storage: Collect environmental samples (e.g., activated sludge, freshwater, soil) in sterile containers. For biomass, centrifuge and store the pellet at -20°C until DNA extraction. Filter large-volume water samples through polycarbonate membranes (0.22 µm pore size) and store the filters at -20°C [34].

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit, QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol to ensure consistency and efficiency [34] [36].

- DNA Quality Control: Assess DNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop). High-quality DNA typically has a 260/280 ratio of ~1.8-2.0. Low 260/230 ratios may indicate the presence of residual inhibitors from the sample matrix [34].

Primer and Probe Design

- Target Selection: For ARG quantification, primers and probes must be highly specific to the target gene sequence. Utilize in silico tools and existing literature for design [36] [33].

- Validation: Primer specificity and optimal annealing temperature should be determined experimentally through temperature gradient PCR and analysis of melt curves (for SYBR Green assays) or in silico tools followed by gel electrophoresis to confirm a single amplicon of the expected size [34] [33].

Detailed qPCR Protocol

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mix containing 1x qPCR master mix (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan), forward and reverse primers (typically 0.2-0.5 µM each), and template DNA (typically 2 µL per reaction). Adjust volumes with nuclease-free water [34] [33].

- Thermal Cycling: Run reactions on a real-time PCR instrument with a standard protocol: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s (denaturation), primer-specific annealing temperature (e.g., 55-60°C) for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min (extension) [34].

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve using a serial dilution of a known concentration of the target gene (e.g., plasmid DNA). Use this curve to interpolate the quantity of the target in unknown samples based on their Ct values [33] [31].

Detailed ddPCR Protocol

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mix similar to qPCR but using a ddPCR supermix (e.g., QX200 ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix or ddPCR Supermix for Probes from Bio-Rad). The total reaction volume is typically 20-22 µL [34] [37].

- Droplet Generation: Load the reaction mix into an 8-channel droplet generation cartridge along with droplet generation oil. Use a droplet generator (e.g., QX200 Droplet Generator, Bio-Rad) to create thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets [34].

- PCR Amplification: Transfer the emulsion to a 96-well PCR plate and run a conventional end-point PCR protocol on a thermal cycler. The cycling conditions are similar to qPCR but with a final droplet stabilization step [34] [37].

- Droplet Reading and Analysis: After amplification, place the plate in a droplet reader (e.g., QX200 Droplet Reader, Bio-Rad) that reads each droplet sequentially. The software counts the positive and negative droplets and uses Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration of the target DNA in copies/µL [34] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of qPCR and ddPCR assays relies on a core set of reliable reagents and instruments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ARG Quantification

| Category | Specific Product Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN) [34] | Efficiently extracts high-quality DNA from complex, inhibitor-rich samples like soil, sludge, and feces. |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green Master Mix, TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix [34] | Contains all components for the qPCR reaction. SYBR Green binds double-stranded DNA; TaqMan uses a target-specific probe for higher specificity. |

| ddPCR Master Mixes | QX200 ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix, ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad) [34] [37] | Formulated for optimal droplet stability and PCR efficiency within the water-in-oil emulsion system. |

| Droplet Generation Oil | DG Cartridges and Oil for Probes or EvaGreen (Bio-Rad) [34] | Specialized oil used to generate stable, uniform droplets during the partitioning process. |

| Primers & Probes | Custom-designed, strain-specific primers and hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan) [34] [36] | Designed for high specificity to the target ARG sequence. Crucial for assay accuracy and minimizing false positives. |

| Digital PCR Systems | QX200 ddPCR System (Bio-Rad), QIAcuity (QIAGEN) [37] [38] | Integrated systems for droplet generation, thermal cycling, and droplet reading. Nanoplate-based systems (QIAcuity) offer a more streamlined workflow. |

The choice between qPCR and ddPCR is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific research question and sample type.

Choose qPCR if: Your project requires high-throughput analysis of a large number of samples, the target ARG is expected to be moderately to highly abundant, the sample is known to be clean with minimal inhibitors, and your budget is a primary constraint. qPCR remains a powerful, cost-effective, and well-established workhorse for many applications [32] [36] [39].

Choose ddPCR if: Your research focuses on the absolute quantification of ARGs without relying on standards, you are working with low-abundance targets or need to detect small fold-changes, or your samples are complex and contain PCR inhibitors (e.g., wastewater, soil, feces). ddPCR's partitioning technology provides unparalleled sensitivity, precision, and robustness under these challenging conditions, making it the definitive tool for the most demanding ARG quantification studies [34] [35] [31].

For a comprehensive investigation of antibiotic resistance gene distribution across hosts and environments, a synergistic approach may be optimal: using qPCR for initial, broad screening and leveraging ddPCR for the absolute, precise quantification of critical, low-abundance ARGs in the most complex sample matrices.

The rapid spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most significant public health threats globally, with estimates suggesting AMR may claim 10 million lives annually by 2050 [40]. The rise of affordable whole-genome sequencing has transformed AMR surveillance, enabling researchers to investigate the distribution of resistance genes across diverse hosts and environments through computational annotation pipelines [41] [42]. These bioinformatic tools identify known antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and mutations in bacterial genomes, allowing for large-scale genomic epidemiology studies that track the dissemination of resistance mechanisms across clinical, agricultural, and environmental settings [40] [43].

Within this context, three platforms have emerged as fundamental resources for AMR research: AMRFinderPlus from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) with its Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI), and ResFinder from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) [40] [41] [42]. Each offers distinct approaches to detecting resistance determinants, with variations in database curation, annotation methodologies, and functional capabilities that influence their application in research settings. This guide provides an objective comparison of these tools' performance characteristics, supported by experimental data, to assist researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies for investigating ARG distribution across host species.

AMRFinderPlus and NCBI's Reference Gene Catalog

AMRFinderPlus is a tool developed by NCBI that identifies acquired antimicrobial resistance genes, stress response genes, virulence factors, and point mutations in assembled bacterial nucleotide or protein sequences [44] [41]. Its underlying database, the Reference Gene Catalog, incorporates a comprehensive collection of curated AMR elements, including genes conferring resistance to 31 classes of drugs and point mutations contributing to resistance to 25 drug classes [41]. A distinctive feature of AMRFinderPlus is its classification of genes into "core" (primarily AMR genes) and "plus" categories (encompassing stress response, virulence, and biocide resistance elements), allowing researchers to focus analyses based on their specific research questions [41].

The tool employs a dual detection approach, utilizing both BLAST with manually curated cutoffs and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to identify resistance determinants [41]. This multi-faceted methodology enhances detection sensitivity for divergent resistance genes while maintaining specificity through carefully validated thresholds. AMRFinderPlus is integrated into NCBI's Pathogen Detection pipeline, where it processes hundreds of thousands of bacterial isolates, with results publicly available through the Isolate Browser and MicroBIGG-E platforms [44].

CARD and the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI)

The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) is a bioinformatic database that employs the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) as its foundational organizing principle for resistance genes, their products, and associated phenotypes [45] [43]. This ontological approach provides a robust classification system that links molecular sequences to their antibiotic targets, resistance mechanisms, and associated scientific literature. As of recent statistics, CARD contains 8,582 ontology terms, 6,442 reference sequences, 4,480 SNPs, and 6,480 AMR detection models [45].

CARD's analytical component, the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI), functions as the primary tool for resistome prediction from molecular sequences [43]. RGI operates through multiple detection models, including homology-based searches, SNP mutations, and protein variant models, enabling comprehensive identification of both acquired resistance genes and chromosomal mutations [45] [43]. The database is rigorously curated, incorporating only sequences available in GenBank and associated with peer-reviewed publications, with an emphasis on experimental validation of resistance mechanisms [43] [46].

ResFinder and PointFinder

ResFinder is an open web-based resource specifically designed to identify acquired antimicrobial resistance genes in bacterial genomes, with an emphasis on facilitating analysis for researchers with limited bioinformatics experience [47] [42]. Developed by the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE), ResFinder specializes in detecting horizontally acquired resistance genes, while its companion tool, PointFinder, focuses on identifying chromosomal mutations conferring resistance in specific bacterial species [47] [42].

A distinctive feature of the ResFinder pipeline is its implementation of the KMA (k-mer alignment) tool, which enables direct alignment of raw sequencing reads against its redundant databases, bypassing the computationally intensive genome assembly process [42]. This approach significantly reduces analysis time, with processing of typical whole-genome sequencing samples completed in under 10 seconds [42]. Since its original publication in 2012, ResFinder has expanded to include phenotypic prediction based on identified genotypes for selected bacterial species, enhancing its utility for clinical surveillance applications [42].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of AMR Annotation Tools

| Feature | AMRFinderPlus | CARD/RGI | ResFinder/PointFinder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Developer | NCBI | McMaster University | Technical University of Denmark |

| Database Organization | Reference Gene Catalog | Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) | Manually curated FASTA files |

| Last Update | 2021 (cited in literature) | Continuously updated | 2024 (software and database) |

| Detection Scope | Acquired genes, point mutations, stress response, virulence | Acquired genes, mutations, efflux pumps, enzymatic resistance | Acquired genes (ResFinder), chromosomal mutations (PointFinder) |

| Analysis Approach | BLAST with curated cutoffs & HMMs | Multiple models: homology, SNP, protein variant | KMA for raw reads, BLAST+ for assemblies |

| Gene Coverage | 6,428 genes (2020 version) | 6,442 reference sequences | Species-specific focus |

| Mutation Coverage | 682 point mutations (2020 version) | 4,480 SNPs | Limited to specific bacterial pathogens |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Validation

Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

Independent validation studies have provided performance metrics for these annotation tools under controlled conditions. In a comprehensive assessment using the abritAMR platform (which utilizes AMRFinderPlus as its detection engine) tested against 1,500 bacteria and 415 resistance alleles, the system demonstrated 99.9% accuracy, 97.9% sensitivity, and 100% specificity when compared to PCR and reference genomes [48]. The pipeline showed exceptional performance for high-risk AMR gene classes, including carbapenemases and ESBLs, with 99.9% accuracy, 98.9% sensitivity, and 100% specificity [48].

A 2025 comparative assessment examining annotation tools for Klebsiella pneumoniae genomes evaluated eight popular tools, including AMRFinderPlus, RGI (using CARD), and ResFinder [46]. This analysis revealed that while all tools performed well, they exhibited differences in gene annotation completeness, which subsequently affected the performance of machine learning models trained to predict resistance phenotypes. The study highlighted that database curation practices significantly influenced annotation results, with tools employing stringent validation criteria (like CARD) sometimes excluding putative resistance genes that other systems might include [46].

Concordance with Phenotypic Testing

A critical measure of utility for AMR annotation tools is their ability to correlate genotypic findings with phenotypic resistance patterns. In a validation study examining 864 Salmonella isolates, genomic predictions generated using AMRFinderPlus demonstrated 98.9% concordance with agar dilution phenotypic testing results [48]. Similarly, a study of mercury-resistant Salmonella isolates found complete agreement between AMRFinderPlus genotypic calls and phenotypic resistance for both antimicrobial compounds and heavy metals [41].

The ResFinder platform has incorporated phenotypic prediction directly into its analytical pipeline since version 4.0, providing interpretations for 3,124 different gene variants based on published literature and manual curation [42]. This functionality represents a significant advancement toward translating genomic findings into clinically relevant predictions, though its performance varies across bacterial species and antibiotic classes.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics from Validation Studies

| Performance Measure | AMRFinderPlus | CARD/RGI | ResFinder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 99.9% (abritAMR validation) [48] | Varies by organism and drug class [46] | High concordance for targeted species [42] |

| Sensitivity | 97.9% (abritAMR validation) [48] | Comprehensive for curated genes [46] | 97.5% for targeted alleles [42] |

| Specificity | 100% (abritAMR validation) [48] | High for validated mechanisms [43] | 99.8% for targeted alleles [42] |

| Phenotypic Concordance | 98.9% (Salmonella spp.) [48] | Not explicitly reported | High for specific species [42] |

| False Negative Sources | Contig breaks in high-GC genes; multiple allele collapse [48] | Stringent validation excludes some putative genes [46] | Primarily novel or divergent variants [42] |

| Limitations | Partial genes at contig breaks; complex allele families [48] | Less clinically focused; may include research-grade entries [42] | Species-specific for mutation detection [47] |

Comparative Performance in Knowledge Gap Identification

The 2025 comparative assessment by Sratonasthan et al. provided unique insights into how different annotation tools perform in identifying knowledge gaps in AMR mechanisms [46]. Researchers built "minimal models" of resistance using only known markers from each database to predict binary resistance phenotypes for 20 antimicrobials in Klebsiella pneumoniae. The performance of these models revealed where known resistance mechanisms insufficiently explained observed phenotypic resistance, thereby highlighting priorities for novel marker discovery.

This analysis found that the choice of annotation tool and reference database significantly influenced model performance, with variations in the completeness of gene annotations across tools [46]. Importantly, the study demonstrated that for some antibiotic classes, even the most comprehensive databases remained insufficient for accurate phenotypic classification, underscoring the need for continued database expansion and refinement.