Integrating Genomic Sciences with a One Health Approach: From Pathogen Surveillance to Precision Medicine

This article explores the transformative role of genomic sciences within the One Health framework, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health.

Integrating Genomic Sciences with a One Health Approach: From Pathogen Surveillance to Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of genomic sciences within the One Health framework, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, methodological applications, and optimization strategies for genomic surveillance and analysis. The content delves into how cross-species genomic data is revolutionizing pandemic preparedness, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) tracking, and the management of zoonotic diseases. It also addresses critical challenges in data integration and bioinformatics, evaluates the comparative effectiveness of One Health genomics against traditional siloed approaches, and discusses future directions for implementing these technologies in biomedical research and clinical practice.

The One Health Genomic Paradigm: Connecting Human, Animal, and Ecosystem Health

Defining the One Health Framework and Its Imperative in Modern Genomics

The One Health framework represents a transformative approach to public health that recognizes the inextricable linkages between human, animal, and environmental health. This whitepaper examines the critical imperative of integrating One Health principles with modern genomic sciences to address complex global health challenges. Through advanced genomic technologies including high-throughput sequencing, bioinformatic analyses, and real-time surveillance, researchers can now decode complex biological interactions across species and ecosystems with unprecedented precision. This technical guide explores methodological frameworks, experimental protocols, and practical applications of genomics within the One Health paradigm, providing researchers and drug development professionals with actionable strategies for implementing integrated health solutions.

Conceptual Foundation and Definition

One Health is defined as "an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems" [1] [2]. This approach recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent [1]. The framework mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines, and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems while addressing collective needs for healthy food, water, energy, and air [2].

The conceptual foundation of One Health rests on several key principles [3] [2]:

- Equity between sectors and disciplines

- Sociopolitical and multicultural parity and inclusion of marginalized voices

- Socioecological equilibrium seeking harmonious balance in human-animal-environment interactions

- Stewardship and responsibility for sustainable solutions

- Transdisciplinarity and multisectoral collaboration across modern and traditional knowledge systems

Historical Evolution and Contemporary Relevance

While the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health has been recognized for centuries, the formalized One Health concept gained significant traction in the early 2000s in response to emerging zoonotic diseases [4]. The Manhattan Principles established in 2004 by the Wildlife Conservation Society represented a pivotal milestone, explicitly recognizing the critical links between human and animal health and the threats diseases pose to food supplies and economies [3] [4]. This was subsequently refined through the Berlin Principles, which expanded the conceptual framework [3].

The SARS outbreak in 2003 and the subsequent spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 demonstrated the necessity of collaborative, cross-disciplinary approaches to emerging infectious diseases [4]. These events catalyzed international cooperation and institutional recognition of One Health, leading to the formation of the One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) in 2020 by the Quadripartite organizations: the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) [3] [2].

The COVID-19 pandemic has further underscored the urgent need for strengthened One Health approaches, with greater emphasis on connections to the environment and promoting healthy recovery [1]. The pandemic revealed how deeply human health is intertwined with animal health and ecosystem integrity, highlighting the necessity of genomic tools for understanding pathogen emergence and transmission dynamics [5] [6].

The Integration of Genomics into One Health Applications

Genomic Technologies Enabling One Health Solutions

Modern genomic technologies have revolutionized our ability to operationalize the One Health framework across human, animal, and environmental domains. These technologies provide powerful tools for understanding pathogen evolution, transmission dynamics, and host-pathogen interactions at unprecedented resolution [3].

Table 1: Genomic Technologies in One Health Applications

| Technology | Key Features | One Health Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanopore Sequencing | Portable, real-time sequencing, long reads, direct RNA sequencing | Field-based pathogen detection, outbreak surveillance, antimicrobial resistance monitoring | [5] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Comprehensive genomic data, high resolution | Pathogen characterization, transmission tracking, antimicrobial resistance research | [6] |

| Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) | Culture-independent, unbiased pathogen detection | Novel pathogen discovery, microbiome studies, environmental surveillance | [7] |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Data integration, computational analysis, visualization | Genomic epidemiology, phylogenetic analysis, predictive modeling | [6] [3] |

Nanopore sequencing represents a particularly transformative technology for One Health applications due to its portability and real-time capabilities [5]. This technology enables genomic analyses in field settings and local laboratories, making genomic surveillance accessible in resource-limited environments common in tropical regions where many emerging zoonotic diseases originate [5] [7]. The MinION device, for example, has been deployed worldwide to break down barriers and improve the accessibility and versatility of genomic sequencing [5].

The declining costs of DNA sequencing have further accelerated the adoption of genomic technologies in One Health contexts. However, this has created new challenges in data management, with annual acquisition of raw genomic data worldwide expected to exceed one zettabyte (one trillion GB) by 2025 [6]. This massive data generation necessitates robust bioinformatic infrastructure and scalable computational workflows to transform raw sequence data into actionable insights [6].

Methodological Framework for Genomic One Health Implementation

Implementing genomic technologies within a One Health framework requires systematic approaches that coordinate activities across human, animal, and environmental sectors. The Generalizable One Health Framework (GOHF) provides a structured five-step process for developing capacity to coordinate zoonotic disease programming across sectors [8]:

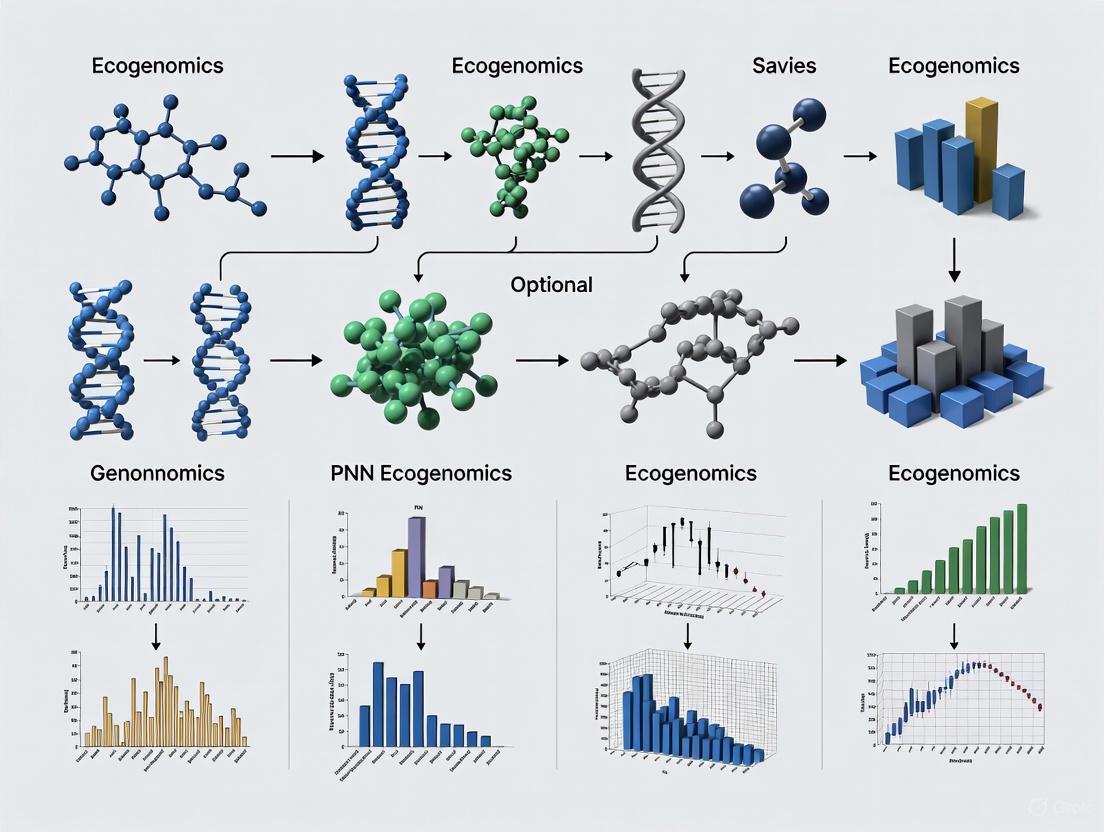

Figure 1: Generalizable One Health Framework (GOHF) for implementing genomic surveillance systems

Step 1: Engagement involves establishing One Health interest by identifying and engaging stakeholders across relevant sectors. This includes prioritizing zoonotic diseases through formalized processes like the One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization (OHZDP) and establishing sustained government support [8].

Step 2: Assessment focuses on mapping existing infrastructure and establishing baseline information on current activities, disease burden, and epidemiologic situations. Infrastructure mapping visualizes mechanisms of communication, collaboration, and coordination between sectors [8].

Step 3: Planning develops strategic roadmaps that define specific objectives, interventions, and resource requirements for genomic One Health implementation. This includes developing integrated surveillance plans that incorporate genomic data from human, animal, and environmental sources [8].

Step 4: Implementation executes the planned activities through coordinated action across sectors. This includes establishing laboratory networks, data sharing platforms, and joint response protocols that leverage genomic technologies [8].

Step 5: Evaluation assesses the effectiveness of implemented activities and systems, using monitoring data to refine approaches and improve outcomes in an iterative process [8].

Technical Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Genomic Surveillance Methodologies

Implementing genomic surveillance within a One Health framework requires standardized methodologies that enable comparable data generation across human, animal, and environmental samples. The following protocols outline key approaches for integrated genomic surveillance:

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Pathogen Genomic Surveillance

- Sample Collection: Coordinate synchronized collection of specimens from human cases, domestic animals, wildlife, and relevant environmental sources (water, soil) using standardized sampling protocols [6] [7].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract DNA and/or RNA using kits that accommodate diverse sample matrices. Implement controls to monitor extraction efficiency and potential contamination [5] [7].

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries using approaches appropriate for the sequencing platform. For nanopore sequencing, this typically involves ligation sequencing kits with native barcoding to enable multiplexing [5].

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on appropriate platforms. For real-time surveillance, utilize portable nanopore sequencers (MinION, GridION) that enable field-based sequencing [5].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform quality control on raw sequencing data (FastQC, NanoPlot)

- Conduct metagenomic classification (Kraken2, Centrifuge) or pathogen-specific assembly (SPAdes, Canu)

- Generate phylogenetic trees (IQ-TREE, BEAST) to infer transmission dynamics

- Screen for antimicrobial resistance genes (ABRicate, CARD) and virulence factors [5] [6] [7]

Protocol 2: Metagenomic Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance

- Sample Collection: Collect samples from targeted reservoirs (human clinical specimens, livestock feces, agricultural soil, wastewater) using consistent sampling methods [6].

- DNA Extraction: Perform high-throughput DNA extraction suitable for diverse sample types. Include extraction controls to monitor performance [6].

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: Prepare libraries without amplification bias and sequence using Illumina or nanopore platforms to achieve sufficient depth for resistance gene detection [6].

- Computational Analysis:

- Trim and quality filter raw reads (Trimmomatic, Porechop)

- Align reads to curated AMR databases (MEGARes, CARD)

- Quantify abundance of resistance genes and mobile genetic elements

- Perform statistical analyses to compare resistance profiles across reservoirs [6]

Reagent Solutions for One Health Genomics

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for One Health Genomic Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application in One Health Genomics | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA/RNA Mini Kit, DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | Efficient extraction from diverse sample matrices (clinical, environmental, veterinary) | Optimize protocols for different sample types; include inhibition removal steps |

| Library Preparation Kits | Nextera XT DNA Library Prep, Ligation Sequencing Kit (Nanopore) | Preparation of sequencing libraries from minimal input DNA | Select kits based on sequencing platform; consider multiplexing requirements |

| Portable Sequencing Devices | MinION, SmidgION (Oxford Nanopore) | Real-time genomic surveillance in field settings | Leverage portability for deployment in remote locations; optimize power supply |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Twist Target Enrichment, SureSelect XT HS | Focused sequencing of pathogen genomes from complex samples | Design panels to cover priority pathogens; optimize for cross-species detection |

| Bioinformatic Tools | CLC Genomics Workbench, Galaxy Platform, BV-BRC | Integrated analysis of genomic data from multiple sectors | Ensure compatibility across data types; implement reproducible workflows |

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics Integration

Computational Frameworks for One Health Genomics

The integration of genomic data within a One Health context requires sophisticated bioinformatic frameworks capable of processing and analyzing heterogeneous datasets from multiple sources. Effective implementation relies on computational infrastructures that support data integration, analysis, and interpretation across disciplinary boundaries [6] [3].

Automated analysis pipelines such as the Automatic Bacterial Isolate Assembly, Annotation and Analyses Pipeline (ASA3P) provide standardized approaches for processing genomic data from diverse sources [6]. These pipelines enable reproducible analyses that facilitate comparisons across human, animal, and environmental isolates, supporting integrated surveillance and outbreak investigations.

Cloud computing infrastructures have become essential for managing the computational demands of One Health genomics. By sharing computational resources across multiple users and institutions, cloud platforms enable scalable analyses while minimizing costs associated with maintaining local computational infrastructure [6]. This approach is particularly valuable for resource-limited settings where establishing local high-performance computing capacity may be challenging.

Data Integration and Visualization

Integrating genomic data with epidemiological, environmental, and clinical information creates a powerful foundation for One Health analytics. The relationships between these data types can be visualized through the following framework:

Figure 2: Data integration framework for One Health genomics

Key data types integrated in this framework include:

- Genomic Data: Pathogen genomes, antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence factors, host genetic information [6] [3]

- Epidemiological Data: Case reports, exposure histories, transmission patterns, risk factors [8]

- Environmental Data: Climate variables, land use patterns, ecological parameters, pollution indicators [1] [7]

- Clinical Data: Patient outcomes, treatment responses, comorbidity information [9]

The integration of these diverse data streams enables the development of predictive models for disease emergence and spread, facilitates molecular epidemiology to track transmission pathways across species boundaries, and supports risk assessment for targeted interventions [3] [8].

Applications in Disease Control and Prevention

Zoonotic Disease Surveillance and Outbreak Response

Genomic technologies have transformed our approach to zoonotic disease surveillance and outbreak response within the One Health framework. Several key applications demonstrate the power of integrated genomic surveillance:

Emerging Infectious Disease Detection: The real-time genomic capabilities of nanopore sequencing have enabled rapid detection and characterization of emerging pathogens at the human-animal-environment interface [5] [7]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, genomic surveillance demonstrated how SARS-CoV-2 variants emerged and spread between human and animal populations, informing targeted control measures [5] [6].

Outbreak Investigation: Whole genome sequencing provides high-resolution data for tracking transmission pathways during zoonotic disease outbreaks. Genomic epidemiology has been successfully applied to investigate outbreaks of diseases including Ebola virus, MERS-CoV, and zoonotic influenza, revealing patterns of both human-to-human and animal-to-human transmission [6] [8]. The application of genomic data during the 2013-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, for example, enabled researchers to distinguish between sustained human-to-human transmission and repeated zoonotic introductions [6].

Table 3: Genomic Applications in Zoonotic Disease Management

| Disease Category | Genomic Application | One Health Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zoonotic Influenza | Whole genome sequencing to track reassortment events and host adaptations | Informed vaccine strain selection and animal control measures | [6] [8] |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | Metagenomic sequencing to track resistance genes across reservoirs | Identified transmission pathways between clinical, agricultural, and environmental settings | [6] [7] |

| Foodborne Pathogens | Genomic溯源 of Salmonella, E. coli, and Campylobacter along food production chains | Enabled targeted interventions at critical control points from farm to consumer | [9] [8] |

| Vector-Borne Diseases | Pathogen genomics combined with vector and host genetics | Revealed complex transmission cycles involving multiple host species | [7] |

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Monitoring

The spread of antimicrobial resistance represents a quintessential One Health challenge that benefits significantly from genomic approaches. Resistance genes can move between bacteria inhabiting humans, animals, and the environment, requiring integrated surveillance across all reservoirs [6] [4].

Genomic studies have revealed that 73% of the global antimicrobial consumption occurs in livestock production, contributing significantly to the emergence and dissemination of resistance genes [6]. The use of genomics has enabled researchers to track the flow of specific resistance mechanisms between agricultural settings, the environment, and clinical environments, informing interventions to slow the spread of resistance [6].

The comprehensive nature of genomic data provides distinct advantages for AMR surveillance compared to traditional phenotypic methods. Whole genome sequencing enables detection of known resistance determinants alongside emerging mechanisms, supports analysis of mobile genetic elements that facilitate resistance gene transfer, and allows for tracking of resistant clones across sectors and geographic boundaries [6].

Implementation Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Technical and Infrastructural Barriers

Despite the demonstrated value of genomic technologies in One Health applications, significant implementation challenges remain:

Resource Limitations: The infrastructure required for genomic sequencing—including reliable electricity, cold chain storage, and computational resources—may be unavailable in many resource-limited settings where zoonotic disease threats are most prominent [7]. Portable sequencing technologies such as the MinION have helped address some of these barriers, but challenges remain in establishing sustainable sequencing capacity [5] [7].

Bioinformatic Capacity: The analysis of genomic data requires specialized computational skills that may not be available across all sectors involved in One Health implementation [6] [7]. Building bioinformatic capacity through training programs and developing user-friendly analytical platforms are essential for expanding access to genomic technologies [6].

Data Integration Challenges: Combining genomic data with epidemiological, clinical, and environmental information presents technical challenges related to data standardization, interoperability, and visualization [3]. Developing common data standards and interoperable platforms is critical for maximizing the utility of genomic data in One Health decision-making [3] [8].

Ethical and Equity Considerations

The application of genomic technologies within One Health raises important ethical considerations that must be addressed:

Equitable Access: There is significant disparity in genomic sequencing capacity between high-income and low-to-middle-income countries, creating an imbalance in who benefits from genomic research [3] [7]. This inequity is particularly problematic since many emerging zoonotic diseases originate in tropical regions where sequencing capacity may be most limited [7].

Data Sovereignty: Genomic research involving biological samples from low and middle-income countries has historically often extracted resources and data without ensuring equitable sharing of benefits [5] [7]. Principles such as the CARE (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics) principles for Indigenous Data Governance and the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing provide frameworks for ensuring that communities and countries maintain authority over their genetic resources and associated data [5].

Digital Colonialism: The dominance of high-income countries in genomic research can lead to inequities where data are extracted from low and middle-income countries but analyzed and utilized elsewhere, limiting local capacity building and benefit [3] [7]. Building local sequencing and bioinformatic capacity through initiatives like the Africa BioGenome Project represents an important step toward addressing these imbalances [7].

Emerging Technologies and Methodological Advances

The future of One Health genomics will be shaped by several technological and methodological developments:

Real-Time Genomic Surveillance: The increasing portability and decreasing cost of sequencing technologies will enable more widespread implementation of real-time genomic surveillance at the human-animal-environment interface [5]. The integration of automated sample preparation with portable sequencers will further enhance capabilities for rapid response to emerging threats.

Single-Cell Genomics: Advances in single-cell sequencing will enable more precise characterization of microbial communities and host-pathogen interactions across different reservoirs, providing unprecedented resolution for understanding transmission dynamics [5].

AI-Enhanced Analytics: Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches will increasingly support the integration of genomic data with other data types, enabling more sophisticated predictive models for disease emergence and spread [10]. These approaches will help identify subtle patterns across complex datasets that may not be apparent through conventional analytical methods.

Pan-Genome Representations: Moving beyond single reference genomes to pan-genome representations that capture the full diversity of pathogens and hosts will enhance our ability to track transmissions and understand adaptive evolution [5]. This approach is particularly valuable for pathogens with significant genomic diversity or those that rapidly evolve in response to selective pressures.

The integration of modern genomic technologies within the One Health framework represents a powerful paradigm for addressing complex health challenges at the human-animal-environment interface. Genomic tools provide unprecedented capabilities for tracking pathogen transmission, understanding antimicrobial resistance dissemination, and detecting emerging threats across species boundaries.

The effective implementation of One Health genomics requires collaborative frameworks that coordinate activities across human health, animal health, and environmental sectors [8]. Methodological standards for genomic surveillance, data sharing, and bioinformatic analysis must be established to enable comparable data generation and interpretation across disciplines [6] [3].

As genomic technologies continue to evolve, their application within One Health approaches will become increasingly essential for global health security. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and building capacity across sectors and geographic regions, the scientific community can harness the power of genomics to promote health for people, animals, and ecosystems in an increasingly interconnected world.

Genomics as a Cross-Cutting Tool for Integrated Health Surveillance

The integration of genomic technologies into public health surveillance represents a paradigm shift in how we detect, monitor, and respond to health threats. Framed within the broader One Health context that recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, genomic surveillance provides unprecedented insights into pathogen evolution, transmission dynamics, and host-pathogen interactions across species and ecosystems [11]. This technical guide examines core applications, methodologies, and implementation frameworks for leveraging genomics as a cross-cutting tool in integrated health surveillance systems, with particular relevance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of human, animal, and environmental health.

The One Health concept underscores that health outcomes across human, animal, and environmental domains are intrinsically linked, necessitating integrated, transdisciplinary approaches to address contemporary health challenges [11]. Genomic technologies serve as a foundational tool within this framework by enabling precise characterization of pathogens and their movements across interfaces. The dramatic reduction in sequencing costs—from approximately $10 million per megabase of DNA sequence in 2001 to less than one cent today—has made these tools increasingly accessible and scalable for routine public health applications [12] [13].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provide higher resolution than traditional subtyping technologies, enabling more accurate cluster detection, transmission tracing, and phenotypic characterization of pathogens [13]. When genomic data are integrated with epidemiological, clinical, and environmental information through integrated genomic surveillance (IGS) systems, public health agencies can achieve earlier detection of outbreaks, better understanding of transmission pathways, and more targeted interventions [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing zoonotic diseases, which account for up to 75% of new or emerging infectious diseases and require coordinated investigation across human and animal populations [15].

Core Applications and Quantitative Impact

Genomic surveillance delivers actionable insights across diverse public health domains, from foodborne illness outbreaks to antimicrobial resistance monitoring. The table below summarizes key application areas with specific examples and documented impacts.

Table 1: Applications and Documented Impact of Genomic Surveillance in Public Health

| Application Area | Specific Use Cases | Key Impact Metrics | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outbreak Detection & Investigation | Foodborne pathogens (Listeria, Salmonella), COVID-19 variant tracking | Listeria: Increased detected clusters from 14 to 21 annually; median cases per cluster decreased from 6 to 3 | [13] |

| Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Surveillance | Carbapenemase-producing organisms (CPOs), Mycobacterium tuberculosis | WGS enables comprehensive AMR gene detection vs. traditional PCR; identifies resistance mechanisms | [16] [17] [13] |

| Zoonotic Disease Monitoring | Pathogen discovery in reservoir hosts, interspecies transmission tracking | 75% of new/emerging infectious diseases have zoonotic origins | [15] |

| Vaccine & Therapeutic Development | Seasonal influenza monitoring, SARS-CoV-2 variant characterization | Informs diagnostic tests, treatments, and vaccine updates | [13] |

Genomic surveillance has transformed public health response to foodborne illnesses. Prior to implementation, many outbreaks went undetected or were identified only after extensive spread. The integration of WGS into foodborne disease surveillance has enabled more rapid and precise intervention, with the number of Listeria outbreaks resolved through identification of contaminated food sources increasing from one to nine per year following implementation [13]. Similarly, genomic surveillance of carbapenemase-producing organisms in Washington State demonstrated high congruence between genomic and epidemiologically defined clusters, with genomic data helping to refine linkage hypotheses and address gaps in traditional surveillance [16] [17].

For antimicrobial resistance, WGS provides superior resolution for cluster investigations compared to traditional methods such as multilocus sequence typing (MLST) [16] [17]. The technology enables detection of resistance genes and differentiation between related and unrelated cases, informing infection control measures and antimicrobial stewardship programs [16]. Beyond human health, genomic applications extend to environmental and agricultural domains within the One Health framework, including wastewater surveillance for community-level pathogen monitoring and genomic breeding programs for improving food security in tropical regions [15] [7].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Integrated Genomic Surveillance Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for integrated genomic surveillance, from sample collection to public health action:

Detailed Laboratory Methods for Bacterial Pathogen Genomic Surveillance

Based on the Washington State Department of Health's successful implementation for antimicrobial resistance surveillance, the following protocol provides a robust framework for bacterial pathogen genomic characterization [16] [17]:

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Culture bacterial isolates on blood agar plates for 24 hours at 35–37°C

- Extract DNA using magnetic bead-based purification systems (e.g., MagNA Pure 96 Small Volume Kit on an MP96 system)

- Quantify DNA concentration using fluorometric methods and normalize to optimal concentration for library preparation

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare paired-end DNA libraries using Illumina DNA Prep kit with Nextera DNA CD indexes

- Perform quality control on libraries using fragment analysis or qPCR

- Sequence on Illumina MiSeq System using 2×250 bp (500-cycle) v2 kit to achieve minimum 40× average read depth

- Repeat sequencing for samples failing QC metrics (<40× coverage, <1 Mb genome size, >500 assembly scaffolds)

Quality Control Thresholds: The following table outlines essential QC parameters and thresholds for ensuring high-quality genomic data:

Table 2: Quality Control Parameters for Genomic Sequencing

| Parameter | Threshold | Remedial Action |

|---|---|---|

| Average Read Depth | ≥40× | Repeat sequencing |

| Genome Size | ≥1 Mb | Investigate extraction issues |

| Assembly Scaffolds | <500 | Optimize library preparation |

| Assembly Ratio SD | ≤2.58 | Check for contamination |

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The bioinformatics workflow for genomic surveillance involves multiple steps to transform raw sequencing data into actionable insights:

Implementation with CDC PHoeNIx Pipeline:

- Perform general bacterial analysis including quality control, de novo assembly, taxonomic classification, and AMR gene detection using the CDC PHoeNIx pipeline

- Process PHoeNIx outputs through specialized bacterial genomic surveillance pipelines (e.g., BigBacter) for phylogenetic analysis and cluster differentiation

- Cluster samples genomically using PopPUNK (version 2.6.0) and calculate accessory distances and core SNPs within each genomic cluster

- Identify and mask recombinant regions using Gubbins (version 3.3.1)

- Generate phylogenetic trees and distance matrices using IQTREE2 (version 2.2.2.6) with appropriate substitution models

- Link genomic outputs to epidemiological metadata for joint analysis and visualization in R and Nextstrain Auspice

Cluster Definition Criteria:

- Genomically linked: Core genome sequences closely related (<10 single-nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs]) or larger SNP distance explained by sample collection dates

- Epidemiologically linked: Cases linked by traditional epidemiology but not meeting genomic linkage criteria

- Epidemiologically and genomically linked: Supported by both epidemiological assessment and genomic data [16] [17]

Technical Infrastructure and Data Management

Effective genomic surveillance requires robust technical infrastructure to handle the substantial computational and data storage demands of sequencing data. Specialized file formats have been developed to optimize analysis speed and storage efficiency for quantitative genomic data.

The D4 (dense depth data dump) format represents an innovation specifically designed for sequencing depth data, balancing improved analysis speeds with efficient file size [18]. The format uses an adaptive encoding scheme that profiles a random sample of aligned sequence depth to determine an optimal encoding strategy, taking advantage of the observation that depth values often have low variability in many genomics assays.

Table 3: Technical Solutions for Genomic Data Management

| Component | Solution Options | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Data Format | D4 Format, bigWig, bedGraph | D4 offers adaptive encoding, fast random access, better compression for depth data [18] |

| Analysis Platform | CDC PHoeNIx, BigBacter, Illumina DRAGEN | Standardized pipelines, recombination-aware analysis, integration with public health systems [16] |

| Data Integration | Custom R scripts, Nextstrain Auspice | Combines genomic and epidemiological data for visualization and interpretation [16] |

| Cloud Infrastructure | GVS (Genomic Variant Store) | Enables joint calling across large datasets (>245,000 genomes in All of Us program) [19] |

For large-scale genomic initiatives such as the All of Us Research Program, which has released 245,388 clinical-grade genome sequences, specialized cloud-based variant storage solutions like the Genomic Variant Store (GVS) have been developed to enable efficient querying and analysis of massive genomic datasets [19]. These infrastructures are essential for supporting the joint calling and variant discovery processes required for population-scale genomic surveillance.

Implementation Framework and Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of genomic surveillance requires careful consideration of technical requirements, workforce development, and ethical frameworks. The following table provides essential components for establishing genomic surveillance capabilities:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Surveillance

| Category | Specific Products/Technologies | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq, NovaSeq 6000, Oxford Nanopore | MiSeq suitable for smaller batches; NovaSeq for high-throughput; Nanopore for portability [16] [7] |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep with Nextera DNA CD indexes, Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep | Target enrichment for specific pathogens; hybrid capture for zoonotic pathogen monitoring [15] [16] |

| Analysis Tools | CDC PHoeNIx, PopPUNK, Gubbins, IQTREE2 | Open-source pipelines optimized for public health pathogen characterization [16] [17] |

| Data Visualization | Nextstrain Auspice, R with custom scripts | Phylogenetic trees integrated with epidemiological data for outbreak investigation [16] |

Workforce and Infrastructure Requirements

Building sustainable genomic surveillance capacity requires investments beyond sequencing equipment alone [12] [13]:

- Bioinformatics Expertise: Critical need for professionals trained in current genomic analysis methods; difficulty in recruiting represents a significant bottleneck

- Cross-disciplinary Training: Need to integrate genomics training into microbiology and epidemiology programs to develop hybrid expertise

- Data Integration Capabilities: Systems for combining genomic, epidemiological, and clinical data remain in early development stages but are crucial for effective public health response

- Ethical and Legal Frameworks: Addressing data privacy, ownership, and sharing concerns, particularly for human genomic sequences included in public health data

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite its transformative potential, genomic surveillance implementation faces several challenges [12] [7]:

- Cost Considerations: While sequencing costs have decreased dramatically, total costs including sample processing, metadata collection, and expert analysis remain substantial

- Infrastructure Heterogeneity: Bioinformatics platforms, cloud storage, and analytic pipelines remain fragmented across jurisdictions, hindering interoperability

- Ethical and Legal Barriers: Data privacy concerns and varying data-sharing laws create inconsistencies in implementation across regions

- Regulatory Hurdles: Sequencing-based diagnostics face regulatory challenges due to pipeline variability and lack of standardization

The Public Health Bioinformatics Fellowship programs and Pathogen Genomics Centers of Excellence (PGCoEs) represent promising models for addressing these challenges through shared resources, training, and standardized approaches [12].

Genomic technologies have evolved from specialized research tools to essential components of integrated health surveillance systems within the One Health framework. The precise characterization of pathogens and their transmission pathways across human, animal, and environmental interfaces enables more targeted and effective public health interventions. As demonstrated by successful implementations in food safety, antimicrobial resistance monitoring, and pandemic response, genomic surveillance provides the resolution necessary to detect outbreaks earlier, trace transmission sources more accurately, and understand pathogen evolution more completely.

Future advancement will require continued investment in cross-disciplinary workforce development, interoperable data systems, and ethical frameworks that facilitate responsible data sharing. The integration of metagenomic approaches for unbiased pathogen detection, combined with portable sequencing technologies, promises to further transform public health capabilities—particularly in resource-limited tropical regions where health challenges are most acute [7]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, genomic surveillance offers not just a reactive tool for outbreak response, but a proactive foundation for understanding disease ecology and developing more effective countermeasures against health threats spanning the One Health spectrum.

The One Health framework represents a transformative approach to managing global health challenges, recognizing the profound interconnections between human, animal, plant, and environmental health. In an era characterized by globalization, climate change, and increasing antimicrobial resistance, genomic sciences have emerged as a critical tool for understanding these complex interactions. This whitepaper examines key global initiatives and policy drivers that are advancing the integration of genomics within the One Health paradigm, from high-level United Nations deliberations to groundbreaking continental projects like the African BioGenome Project. The strategic application of genomic technologies across these sectors enables precise pathogen identification, real-time outbreak tracking, and insights into host-pathogen co-evolution, ultimately strengthening global health security and sustainable development [20]. These initiatives collectively address the urgent need for coordinated, cross-sectoral approaches to mitigate biological threats through advanced genomic surveillance and research.

Global Policy Frameworks: UNGA and International Governance

United Nations High-Level Meetings on Health

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) has established critical policy frameworks that directly and indirectly advance the One Health genomic sciences agenda. The Fourth UN High-level Meeting on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing (HLM4) in September 2025 resulted in the political declaration "Equity and integration: transforming lives and livelihoods through leadership and action on noncommunicable diseases and the promotion of mental health" [21]. This declaration, while primarily focused on human health, creates important linkages to broader One Health objectives by emphasizing whole-of-government and whole-of-society collaboration to address underlying social, economic, commercial, and environmental drivers of health risks [21].

Concurrently, the UNGA79 Science Summit emphasized leveraging interdisciplinary solutions to bridge health divides, with mental health, digital healthcare, and One Health frameworks emerging as focal areas. Discussions highlighted the transformative power of integrating science, technology, and innovation (STI) across sectors to address systemic barriers including inequitable resource distribution and the impacts of climate change on health and agriculture [22]. These high-level policy dialogues create an enabling environment for genomic research that transcends traditional sectoral boundaries and addresses health challenges at the human-animal-environment interface.

Global Coordination Mechanisms

Beyond specific declarations, ongoing UN-based processes provide critical platforms for advancing the One Health genomic agenda. The Quadripartite Collaboration between the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Health Organization (WHO), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), and United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) has developed a One Health-driven joint plan of action to integrate systems and capacity for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance, governance framework, and cross-sectional interventions worldwide [23]. This collaboration recognizes that timely integrated data on AMR and antimicrobial use across human, animal, and environmental sectors is critical to curbing AMR's devastating impact, which is projected to cause 10 million deaths annually by 2050 if left unaddressed [23].

Table 1: Key Policy Frameworks Supporting One Health Genomics

| Policy Framework | Lead Organizations | Primary Focus Areas | Relevance to Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNGA HLM4 Political Declaration (2025) | UN Member States | NCDs, mental health, health equity | Creates enabling policy environment for cross-sectoral research |

| Quadripartite One Health Joint Plan of Action | FAO, WHO, WOAH, UNEP | Antimicrobial resistance, zoonotic diseases | Promotes integrated genomic surveillance systems |

| European One Health AMR Partnership | 53 organizations from 30 countries | Antimicrobial resistance | Fosters collaborative genomic research on AMR |

| UK Biological Security Strategy | UK Government | Biological security, pandemic preparedness | Funds genomic surveillance initiatives like GAP-DC |

Major Genomic Initiatives Under the One Health Paradigm

The African BioGenome Project (AfricaBP)

The African BioGenome Project (AfricaBP) is a transformative, continent-wide initiative that exemplifies the application of One Health principles to genomic sciences. This pan-African effort aims to sequence, catalog, and study the genomes of Africa's rich and diverse biodiversity, with an ambitious goal of sequencing approximately 105,000 non-human eukaryotic genomes including plants, animals, fungi, and protozoa [24]. The project operates through the Digital Innovations in Africa for a Sustainable Agri-Environment and Conservation (DAISEA) network, fostering scientific collaborations and partnerships to provide a platform for innovations and policy change across Africa through biodiversity genomics [25].

AfricaBP's economic implications are substantial. A cost-benefit analysis of the South African Beef Genomics Program revealed that a total investment of US$44 million over 10 years was expected to yield at least US$139 million in benefits, with an economic return of 18.70% and a Benefit-Cost Ratio of 3.1 [24]. Similarly, a case study on the proposed 1000 Moroccan Genome Project projected a Benefit-Cost Ratio of 3.29, indicating US$3.29 in benefits for every US$1 invested [24]. These economic analyses demonstrate the significant value proposition of strategic investments in genomic infrastructure within the One Health framework.

Genomics for Animal and Plant Disease Consortium (GAP-DC)

The Genomics for Animal and Plant Disease Consortium (GAP-DC), launched in July 2023 and supported by Defra and UKRI, represents a sophisticated implementation of One Health genomics in a high-income context. This initiative addresses complexities in the UK's distributed animal and plant health science landscape by bringing together key organizations in pathogen detection and genomics for terrestrial and aquatic animal health (APHA, Royal Veterinary College, CEFAS, The Pirbright Institute) and plant health (Fera Science, Forest Research) [20].

GAP-DC's scope is defined by six interconnected work packages, each addressing a critical aspect of genomic surveillance:

- Enhancing frontline pathogen detection at high-risk locations using satellite or mobile laboratory facilities

- Targeting pathogen spillover between wild and farmed/cultivated populations

- Advancing identification of disease agents contributing to syndromic or complex diseases

- Developing frameworks for detecting and managing outbreaks of new and re-emerging diseases

- Exploring innovative strategies for mitigating endemic diseases

- Enhancing coordination among key stakeholders and end users [20]

This comprehensive approach facilitates collaboration and knowledge exchange between agencies, disciplines, and disease systems while exploring innovative methodologies such as environmental metagenomics [20].

Cross-Species Genomic Analyses at Purdue University

Purdue University's One Health initiative exemplifies the innovative research approaches advancing the field. A project titled "Using Across-Phyla Methods To Increase Genomic Prediction Accuracy To Improve Health and Food Security" investigates whether techniques developed to study traits in animal and plant genetics can be adapted to explore similar questions in the human genome [10]. This cross-species genomic analysis represents a significant departure from traditional siloed approaches to genetics research.

The project builds on access to large-scale phenotypic and genome databases, including human genetic biobanks (23andMe, UK Biobank), plant genetic biobanks (EnsemblPlants, JGI Plant Gene Atlas), and livestock animal systems datasets through the Purdue Animal Sciences Research Data Ecosystem [10]. By leveraging methods developed in animal genetics that utilize abundant data and advanced predictive techniques, and applying them to human genetic datasets (which often have more restrictive data access), the research team aims to improve genomic predictions across all species within the One Health context [10].

Table 2: Major One Health Genomic Initiatives and Their Focus Areas

| Initiative | Geographic Scope | Primary Objectives | Key Achievements/Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| African BioGenome Project | Continental Africa | Sequence 105,000 non-human eukaryotic species; build genomic capacity | Trained 401 researchers across 50 African countries in 2024 |

| GAP-DC | United Kingdom | Coordinate animal and plant disease genomics across government agencies | Six work packages addressing disease detection, spillover, and outbreak management |

| Purdue Cross-Species Genomics | United States | Develop cross-species genomic prediction methods | Leveraging animal genetics models for human health insights |

| European One Health AMR Partnership | 30 European countries | Combat antimicrobial resistance through collaborative research | 10-year program launched in 2025 involving 53 organizations |

Technological Innovations and Methodological Approaches

Artificial Intelligence and Genomic Surveillance

Artificial intelligence (AI) applications are rapidly transforming One Health genomic surveillance, particularly in addressing complex challenges like antimicrobial resistance (AMR). A recent scoping review identified that AI is widely applied to combat AMR across different sectors (human, animal, and environmental health), with key opportunities including rapid identification of resistant pathogens, AI-powered surveillance and early warning systems, integration of diverse datasets, and support for drug discovery and antibiotic stewardship [23].

The review, which analyzed 43 studies after screening 543 initial candidates, found that AI systems can integrate genomic data with environmental surveillance to predict resistance hotspots and guide targeted interventions [23]. Initiatives like the Outbreak Consortium demonstrate the potential of AI-driven platforms to map risks using diverse datasets from various sectoral records, thereby fostering more effective antimicrobial stewardship [23]. However, significant challenges remain, such as data standardization issues, limited model transparency, infrastructure and resource gaps, ethical and privacy concerns, and difficulties in real-world implementation and validation [23].

Standardized Experimental Protocols for One Health Genomics

Implementing robust One Health genomic surveillance requires standardized methodologies across diverse sectors and environments. The following experimental protocols represent best practices derived from major initiatives:

Integrated Pathogen Surveillance Protocol

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach to pathogen detection and characterization across human, animal, and environmental samples:

- Sample Collection: Systematic gathering of specimens from human clinical cases, livestock, wildlife, plants, and environmental sources (water, soil)

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Using standardized kits for DNA/RNA extraction across sample types

- Library Preparation: Employing tagmentation-based approaches for rapid, high-throughput sequencing library preparation

- Sequencing: Utilizing both short-read (Illumina) for accuracy and long-read (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) technologies for resolution of complex genomic regions

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Implementing standardized pipelines for assembly, annotation, and phylogenetic analysis

- Data Integration: Combining genomic data with epidemiological metadata for comprehensive analysis [20]

Cross-Species Genomic Prediction Protocol

This methodology, developed by Purdue University researchers, enables the transfer of genomic prediction models across species boundaries:

- Data Harmonization: Standardizing phenotypic and genomic data formats across species

- Feature Alignment: Identifying orthologous genes and comparable traits across species

- Model Training: Developing prediction algorithms using animal genetics datasets with dense phenotypic information

- Model Adaptation: Adjusting trained models for application to human datasets with different characteristics

- Validation: Testing prediction accuracy in target species using cross-validation approaches [10]

Diagram 1: One Health Genomic Surveillance Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for One Health Genomics

Implementing robust One Health genomic research requires specialized reagents and materials optimized for diverse sample types across human, animal, plant, and environmental applications. The following table details essential research reagent solutions and their specific functions within this interdisciplinary field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for One Health Genomic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application in One Health Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-species nucleic acid extraction kits | DNA/RNA purification from diverse sample matrices | Standardized extraction from human, animal, plant, and environmental samples |

| Tagmentation-based library prep reagents | Rapid sequencing library preparation | High-throughput processing for pathogen surveillance across sectors |

| Pan-pathogen PCR master mixes | Amplification of conserved genomic regions | Broad-spectrum pathogen detection in human, animal, and environmental samples |

| Metagenomic sequencing kits | Untargeted sequencing of complex communities | Microbiome analysis across human, animal, and environmental interfaces |

| Hybridization capture reagents | Target enrichment for specific genomic regions | Focused sequencing of zoonotic pathogens or antimicrobial resistance genes |

| Long-read sequencing reagents | Generation of continuous sequence reads | Resolution of complex genomic regions in novel pathogens |

| Reverse transcriptase enzymes | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Detection and characterization of RNA viruses with zoonotic potential |

| Whole-genome amplification kits | Amplification of limited template DNA | Analysis of low-biomass samples from environmental or clinical sources |

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Technical and Infrastructural Barriers

Despite significant advancements, implementing comprehensive One Health genomic surveillance faces substantial technical challenges. Data standardization remains a critical hurdle, as genomic data from human, animal, plant, and environmental sources often utilize different formats, metadata standards, and quality control measures [23]. This lack of interoperability hinders effective integration and analysis across sectors. Additionally, many low- and middle-income countries face significant infrastructure gaps in sequencing capacity, computational resources, and bioinformatics expertise, creating global disparities in One Health genomic capabilities [24].

The AfricaBP Open Institute has made substantial progress in addressing these capacity gaps through its workshop series, which trained 401 African researchers across 50 countries in genomics, bioinformatics, molecular biology, sample collections, and biobanking in 2024 alone [24]. However, sustainable investment remains crucial—African countries allocate an average of just 0.45% of their GDP to research and development, significantly below the global average of 1.7% [24]. This underinvestment hinders the transformation of Africa's intellectual capital into tangible products and services that could boost economic growth through genomic applications.

Ethical Frameworks and Equitable Benefit Sharing

Advancing One Health genomics requires robust ethical frameworks to ensure equitable benefit sharing and appropriate use of genomic data. The AfricaBP has established important precedents through its commitment to equitable data sharing and benefits for the African population [24]. This includes developing policies to safeguard genomic data while promoting accessibility for African researchers, and ensuring that discoveries derived from African biodiversity translate to improved food security, biodiversity conservation, and health outcomes for African communities [24].

Similarly, the integration of AI in One Health applications raises important ethical considerations, including privacy concerns, model transparency, and the need for clear regulatory frameworks to ensure ethical and effective use within the One Health approach [23]. Future directions must prioritize the development of explainable AI systems that provide transparent decision-making processes, particularly when informing public health interventions or policy decisions based on integrated genomic data [23].

Diagram 2: Key Implementation Challenges in One Health Genomics

The integration of genomic sciences within the One Health framework represents a paradigm shift in how we approach complex health challenges at the human-animal-environment interface. Global policy drivers, from UNGA declarations to national biological security strategies, are increasingly recognizing the strategic importance of cross-sectoral genomic surveillance. Initiatives like the African BioGenome Project, GAP-DC, and innovative research at institutions like Purdue University demonstrate the tremendous potential of coordinated genomic approaches to address pressing challenges in food security, antimicrobial resistance, pandemic preparedness, and biodiversity conservation.

Moving forward, realizing the full potential of One Health genomics will require sustained investment in core capacities, development of standardized methodologies and data sharing frameworks, and commitment to equitable partnerships that ensure benefits are broadly shared across sectors and regions. Technological innovations, particularly in artificial intelligence and cross-species genomic analyses, offer promising tools for extracting deeper insights from integrated datasets. However, success will ultimately depend on continued collaboration across traditionally disparate disciplines and sectors, fostering a truly integrated approach to genomic sciences in service of health for all species and the planet we share.

Understanding Zoonotic Spillover and Pandemic Origins through Genomic Lenses

The One Health concept underscores the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, necessitating an integrated, transdisciplinary approach to tackle contemporary health challenges [11]. Zoonotic diseases, which are infections transmitted between animals and humans, account for a substantial proportion of emerging infectious diseases. The genomic revolution has provided unprecedented capabilities to decode complex biological data, enabling comprehensive insights into pathogen evolution, transmission dynamics, and host-pathogen interactions across species and ecosystems [11]. Through the application of high-throughput sequencing technologies and sophisticated computational analyses, researchers can now trace the origins of pandemics with remarkable precision, monitor ongoing transmission events in near real-time, and identify genetic markers associated with increased transmissibility or virulence. This whitepaper explores how genomic technologies are transforming our understanding of zoonotic spillover events and pandemic origins, framed within the integrative context of One Health approaches that connect human, animal, and environmental surveillance systems.

Genomic Technologies for Predicting Zoonotic Spillover Risk

Machine Learning Approaches for Spillover Prediction

Machine learning models represent a frontier in preemptive pandemic preparedness by identifying animal viruses with potential for human infectivity. A significant limitation in this field has been the lack of comprehensive datasets for viral infectivity, which restricts the predictable range of viruses. Recent research has addressed this through two key strategies: constructing expansive datasets across 26 viral families and developing the BERT-infect model, which leverages large language models pre-trained on extensive nucleotide sequences [26].

This approach substantially boosts model performance, particularly for segmented RNA viruses, which are involved with severe zoonoses but have been historically overlooked due to limited data availability. These models demonstrate high predictive performance even with partial viral sequences, such as high-throughput sequencing reads or contig sequences from de novo sequence assemblies, indicating their applicability for mining zoonotic viruses from metagenomic data [26]. Models trained on data up to 2018 have demonstrated robust predictive capability for most viruses identified post-2018, though challenges remain in predicting human infectious risk for specific zoonotic viral lineages, including SARS-CoV-2 [26].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of BERT-infect Model Across Viral Families

| Viral Family | Prediction Accuracy (%) | Notable Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthomyxoviridae | 92.5 | High accuracy for segmented RNA viruses | Requires segment-specific training |

| Coronaviridae | 89.7 | Effective even with partial sequences | Lower performance on SARS-CoV-2 lineage |

| Rotaviridae | 94.2 | Robust across diverse genotypes | Requires extensive validation |

| Paramyxoviridae | 87.9 | Good generalizability | Moderate performance on novel variants |

Experimental Protocol for Viral Infectivity Prediction

The following protocol outlines the methodology for developing and validating machine learning models to predict viral infectivity in humans:

Dataset Curation and Preprocessing

- Viral Sequence Acquisition: Collect viral sequences and metadata from the NCBI Virus Database [26]. For this study, researchers gathered 140,638 sequences from an initial download of 1,336,901 sequences through rigorous filtering.

- Segmented Virus Handling: For segmented RNA viruses (e.g., Orthomyxoviridae, Rotaviridae), group sequences into viral isolates based on metadata combinations. Eliminate redundancy by randomly sampling a sequence for each segment when a single viral isolate contains more sequences than the specified number of viral segments.

- Infectivity Labeling: Label viral infectivity according to host information, excluding sequences collected from environmental samples where host organisms are ambiguous.

- Temporal Partitioning: Divide data into past virus datasets (for model training) and future virus datasets (for evaluating performance on novel viruses). A common approach uses December 31, 2017, as the cutoff date.

Model Development and Training

- Model Selection: Employ pre-trained large language models such as DNABERT (pre-trained on human whole genome) and ViBE (pre-trained on viral genome sequences from NCBI RefSeq) [26].

- Input Preparation: Split viral genomes into 250 bp fragments with a 125 bp window size and 4-mer tokenization.

- Fine-tuning: Fine-tune BERT models using past virus datasets to construct an infectivity prediction model for each viral family. Utilize appropriate hyperparameters for optimization.

- Validation Framework: Implement stratified five-fold cross-validation to adjust for class imbalance of infectivity and virus genus classifications. Set training, evaluation, and test dataset proportions to 60%, 20%, and 20%, respectively.

Performance Evaluation

- Prediction Probability Calculation: For models using subsequence inputs (e.g., BERT-infect, DeePac_vir), calculate prediction probabilities for genomic sequences by averaging predicted scores for subsequences.

- Metrics: Evaluate predictive performance using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and other relevant metrics.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare performance against existing models such as humanVirusFinder, DeePacvir, and zoonoticrank, retrained on the same datasets.

Molecular Epidemiology and Pathogen Genomic Tracing

Genomic Reconstruction of Transmission Dynamics

Molecular epidemiology leverages pathogen genomic data to reconstruct transmission dynamics and identify spillover events. A recent study on mpox transmission in West Africa exemplifies this approach, where researchers sequenced 118 MPXV genomes isolated from cases in Nigeria and Cameroon between 2018 and 2023 [27]. The genomic analysis revealed contrasting transmission patterns: cases in Nigeria primarily resulted from sustained human-to-human transmission, while cases in Cameroon were driven by repeated zoonotic spillovers from animal reservoirs [27].

Phylogenetic analysis enabled researchers to identify distinct zoonotic lineages circulating across the Nigeria-Cameroon border, suggesting that shared animal populations in cross-border forest ecosystems drive viral emergence and spread. The study identified the closest zoonotic outgroup to the Nigerian human epidemic lineage (hMPXV-1) in a southern Nigerian border state and estimated that the shared ancestor of the zoonotic outgroup and hMPXV-1 circulated in animals in southern Nigeria in late 2013 [27]. The analysis further revealed that hMPXV-1 emerged in humans in August 2014 in southern Rivers State and circulated undetected for three years before being identified, with Rivers State serving as the main source of viral spread during the human epidemic [27].

A key genomic signature differentiated sustained human transmission from zoonotic spillovers: APOBEC3 mutational bias. Researchers observed that approximately 74% of reconstructed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the human-transmitted hMPXV-1 lineage were indicative of APOBEC3 editing, a host antiviral mechanism. In contrast, only 9% of reconstructed SNPs across zoonotic transmissions showed this pattern [27]. This molecular signature serves as a reliable marker for distinguishing sustained human-to-human transmission from spillover events.

Table 2: Genomic Features Differentiating Zoonotic vs. Human Transmission in MPXV

| Transmission Type | APOBEC3 Mutation Signature | Genetic Diversity | Phylogenetic Pattern | Representative Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zoonotic Spillover | Minimal (9% of SNPs) | High between isolates | Divergent basal lineages | Cameroon cases (100%) |

| Sustained Human Transmission | Dominant (74% of SNPs) | Limited diversity with shared mutations | Tightly clustered lineages | Nigerian cases (96.3%) |

| Mixed Transmission | Variable | Moderate diversity | Multiple introduction clusters | Border region cases |

Experimental Protocol for Phylogenetic Analysis of Transmission Chains

Sample Collection and Sequencing

- Case Identification: Identify confirmed cases through laboratory testing and epidemiological investigation. For the mpox study, researchers collected samples from 109 cases in Nigeria and 9 cases in Cameroon between 2018-2023 [27].

- Genome Sequencing: Extract viral RNA/DNA and perform whole genome sequencing using high-throughput platforms. Generate near-complete genomes with sufficient coverage for robust phylogenetic analysis.

Genomic Analysis

- Variant Calling: Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and other genetic variations relative to a reference genome using standardized bioinformatics pipelines.

- Mutation Signature Analysis: Quantify the proportion of mutations in dinucleotide contexts associated with host antiviral mechanisms like APOBEC3 activity, which produces a characteristic mutational bias in human-to-human transmission [27].

- Recombination Assessment: Screen for potential recombination events that might confound phylogenetic reconstruction.

Phylogenetic Reconstruction

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Align consensus sequences using appropriate algorithms (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE).

- Evolutionary Model Selection: Determine the best-fitting nucleotide substitution model using model testing software (e.g., ModelTest, jModelTest).

- Tree Building: Construct phylogenetic trees using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods. For the mpox study, researchers reconstructed the clade IIb phylogeny with all available clade IIb sequences [27].

- Lineage Designation: Classify sequences into distinct lineages using a standardized nomenclature system similar to the SARS-CoV-2 Pango nomenclature [27].

Evolutionary Analysis

- Molecular Dating: Estimate the time to most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) using Bayesian evolutionary analysis with appropriate clock models and calibration points.

- Phylogeographic Inference: Reconstruct spatial spread patterns by incorporating sampling location data into phylogenetic models.

- Transmission Classification: Differentiate zoonotic spillover from sustained human-to-human transmission based on phylogenetic positioning and mutational signatures.

The One Health Integration Framework

Transdisciplinary Approaches to Genomic Surveillance

The One Health framework provides an essential paradigm for integrating genomic data across human, animal, and environmental domains to comprehensively address zoonotic threats. This approach recognizes that human health is inextricably linked to animal health and the environment they share [11]. Genomic technologies and bioinformatics tools serve as the connective tissue in this framework, enabling researchers to decode complex biological data and generate actionable insights for health promotion and disease prevention [11].

Successful implementation of One Health genomics requires collaboration among geneticists, bioinformaticians, epidemiologists, zoologists, and data scientists to harness the full potential of these technologies in safeguarding global health [11]. This transdisciplinary approach enhances the precision of public health responses by integrating genomic data with environmental and epidemiological information. Case studies demonstrate successful applications of genomics and bioinformatics in One Health contexts, though challenges remain in data integration, standardization, and ethical considerations in genomic research [11].

The application of One Health genomics extends beyond outbreak response to include predictive surveillance. By monitoring pathogen evolution in animal reservoirs and environmental samples, researchers can identify potential threats before they spill over into human populations. This proactive approach requires sustained investment in interdisciplinary education, research infrastructure, and policy frameworks to effectively employ these technologies in the service of a healthier planet [11].

Historical Perspectives on Pandemic Origins

Genomic analysis of ancient pathogens provides valuable context for understanding the patterns and processes of pandemic emergence throughout human history. Recent research on the Plague of Justinian (AD 541-750), the world's first recorded pandemic, illustrates how ancient DNA can resolve long-standing historical mysteries [28].

For the first time, researchers uncovered direct genomic evidence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium behind the Justinian Plague, in a mass grave at the ancient city of Jerash, Jordan, near the pandemic's epicenter [28]. Using targeted ancient DNA techniques, the team recovered and sequenced genetic material from eight human teeth excavated from burial chambers beneath a former Roman hippodrome that had been repurposed as a mass grave during the mid-sixth to early seventh century [28].

Genomic analysis revealed that plague victims carried nearly identical strains of Y. pestis, confirming the bacterium was present within the Byzantine Empire between AD 550-660 and causing a rapid, devastating outbreak consistent with historical descriptions [28]. A companion study analyzing hundreds of ancient and modern Y. pestis genomes showed that the bacteria had been circulating among human populations for millennia before the Justinian outbreak. Importantly, later plague pandemics did not descend from a single ancestral strain but arose independently and repeatedly from longstanding animal reservoirs, erupting in multiple waves across different regions and eras [28]. This pattern of repeated emergence from animal reservoirs stands in stark contrast to the COVID-19 pandemic, which originated from a single spillover event and evolved primarily through human-to-human transmission [28].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zoonotic Spillover Studies

| Resource/Technology | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | Generate whole genome sequences of pathogens | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 used in All of Us Research Program for clinical-grade sequencing [19] |

| BERT-infect Model | Predict zoonotic potential of viruses from genetic sequences | Leverages LLMs pre-trained on nucleotide sequences to identify human infectivity potential [26] |

| Cytoscape | Visualize complex biological networks and integrate attribute data | Open source platform for visualizing molecular and genetic interaction networks [29] |

| Graphviz | Create diagrams of abstract graphs and networks | Open source graph visualization software for structural representation [30] |

| NCBI Virus Database | Repository of viral sequences and metadata | Source for 140,638 sequences across 26 viral families for training BERT-infect [26] |

| APOBEC3 Mutation Profiling | Differentiate human-to-human transmission from zoonotic spillovers | Identified 74% of SNPs in hMPXV-1 lineage showed APOBEC3 signature vs. 9% in zoonotic cases [27] |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Tools | Reconstruct evolutionary relationships and transmission chains | Used to identify distinct zoonotic MPXV lineages crossing Nigeria-Cameroon border [27] |

| Ancient DNA Techniques | Recover and sequence genetic material from historical samples | Enabled identification of Yersinia pestis in 6th-century mass grave in Jerash, Jordan [28] |

Genomic technologies have fundamentally transformed our ability to understand, predict, and respond to zoonotic spillover events and pandemic origins. Through the application of sophisticated machine learning models, phylogenetic analysis, and molecular epidemiology, researchers can now trace the evolutionary pathways of pathogens with unprecedented precision. The integration of these approaches within a One Health framework that connects human, animal, and environmental surveillance represents the most promising strategy for mitigating future pandemic threats. As genomic technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, their implementation in global surveillance systems will be crucial for early detection and response to emerging zoonotic diseases. The continued development of open-source bioinformatics tools, standardized protocols, and collaborative research networks will ensure that the scientific community remains prepared to address the ongoing challenge of zoonotic disease emergence in an increasingly interconnected world.

Genomic Technologies in Action: Surveillance, Diagnostics, and Outbreak Management

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) for Pathogen Identification and Characterization

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) has revolutionized pathogen surveillance by providing unprecedented resolution for identifying and characterizing disease-causing microorganisms. This transformation is particularly impactful within the One Health framework, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. The emergence of zoonotic diseases and increasing antibiotic resistance has highlighted the critical need for integrated surveillance systems that monitor infectious diseases across all domains [31]. WGS technologies have displaced traditional typing methods by offering complete genetic blueprints of pathogens, enabling public health officials to explore compelling questions about disease transmission, evolution, and virulence with unparalleled precision.

The implementation of WGS represents a fundamental shift from conventional pathogen typing methods. Historically, techniques such as serotyping, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) provided limited discriminatory power for differentiating between closely related bacterial strains [32] [31]. While these methods served as gold standards for decades, they lacked the resolution necessary for accurate phylogenetic analyses and source attribution in complex outbreak scenarios. The advent of WGS has overcome these limitations, providing public health agencies with a tool that supports precise disease control strategies and antimicrobial resistance management on a global scale [33] [31].

Technical Foundations of Pathogen WGS

From Traditional Typing to Genomic Surveillance

The evolution of pathogen typing methodologies reveals a clear trajectory toward increasingly detailed genetic characterization:

- Serotyping (1930s): One of the earliest sub-species differentiation methods based on antigen-antibody reactions

- Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (1980s-2000s): Universal gold standard using restriction patterns of genomic DNA

- Multilocus Sequence Typing (1998-present): Sequence-based approach analyzing seven housekeeping genes

- Whole Genome Sequencing (2010s-present): Comprehensive analysis of the complete genetic material [32]

This historical progression demonstrates how each technological advancement addressed limitations of previous methods. PFGE, while revolutionary for its time, lacked the portability and standardization needed for global surveillance systems. MLST introduced sequence-based portability but suffered from limited discriminatory power due to its focus on only seven housekeeping genes [32]. The variable number tandem repeat (MLVA) method offered improved resolution for outbreak investigations but remained insufficient for evolutionary studies and spatiotemporal investigations [32].

WGS Methodologies and Analytical Approaches

Modern WGS analysis employs several sophisticated bioinformatics approaches for extracting relevant information from sequencing data. The two primary methods for assessing genetic similarity between bacterial strains are:

1. Gene-by-Gene Approach (cgMLST/wgMLST) Core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) compares hundreds or thousands of gene loci across bacterial genomes. This method involves aligning genome assembly data to a predefined scheme containing specific loci and associated allele sequences [32]. Each isolate is characterized by its allele profile, with differences between profiles used to construct phylogenetic relationships. Whole-genome MLST (wgMLST) extends this approach by incorporating accessory genes beyond the core genome, potentially offering higher resolution for closely related clusters [32].