Gene-Environment Interactions in Natural Populations: From Foundational Concepts to Precision Medicine Applications

This article synthesizes the current state of gene-environment (GxE) interaction research, exploring its foundational principles, methodological advancements, and translational applications.

Gene-Environment Interactions in Natural Populations: From Foundational Concepts to Precision Medicine Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes the current state of gene-environment (GxE) interaction research, exploring its foundational principles, methodological advancements, and translational applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it delves into the complex interplay between genetic makeup and environmental exposures in shaping disease risk and treatment outcomes in natural populations. We cover the evolution from candidate-gene studies to multi-omics integration and artificial intelligence, address key challenges like diversity gaps in genomic datasets and analytical hurdles, and examine ethical, legal, and social implications. The article further validates findings through case studies in oncology, neuropsychiatry, and pharmacogenomics, providing a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging GxE insights to propel precision medicine forward.

The GxE Framework: Unraveling the Core Principles and Evolutionary Forces

Gene-environment interaction (G×E) occurs when the effect of an environmental exposure on disease risk differs across individuals with varying genetic backgrounds, or conversely, when the effect of a genotype on disease risk varies across individuals exposed to different environments [1]. This concept moves beyond the nature-versus-nurture debate by recognizing that genetic and environmental factors do not operate independently but instead interact in complex ways to influence phenotypic outcomes and disease susceptibility in natural populations.

The study of G×E is central to the field of genetic epidemiology, which integrates methods from epidemiology, biostatistics, and molecular genetics to understand the genetic contributions to complex diseases [1]. These interactions may provide crucial mechanisms for targeting interventions to individuals who would benefit most from them, such as tailoring drug treatments based on genetics or personalizing disease prevention strategies according to both genetic and environmental risk factors [2].

Statistical Foundations and Definitions

Core Statistical Models

At its simplest, G×E can be investigated using a linear regression model with an interaction term. For a quantitative trait Y, the model can be specified as:

Y = β₀ + β₁G + β₂E + β₃G×E + ε [3]

Where:

- G represents the genotype value

- E represents the environmental factor

- G×E represents their interaction

- β₁ and β₂ represent the main effects of genotype and environment, respectively

- β₃ quantifies the interaction effect

- ε represents random noise

The test for interaction is performed by evaluating whether β₃ differs significantly from zero. This direct test, however, often suffers from low statistical power due to collinearity between G and G×E, which increases the standard error of the parameter estimates [3].

Scale of Measurement and Interaction Types

The detection of G×E depends critically on the scale of measurement—whether effects are measured on an additive or multiplicative scale [1]. The table below summarizes how to interpret interaction effects on these different scales:

Table 1: Interpretation of Gene-Environment Interactions on Different Scales

| Scale of Measurement | No Interaction | Synergistic Interaction | Antagonistic Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Scale | RR₁₁ = RR₀₁ + RR₁₀ - 1 | RR₁₁ > RR₀₁ + RR₁₀ - 1 | RR₁₁ < RR₀₁ + RR₁₀ - 1 |

| Multiplicative Scale | RR₁₁ = RR₀₁ × RR₁₀ | RR₁₁ > RR₀₁ × RR₁₀ | RR₁₁ < RR₀₁ × RR₁₀ |

Abbreviation: RR, relative risk. Subscripts indicate presence (1) or absence (0) of genotype (first digit) and environment (second digit). Adapted from [1].

The choice between additive and multiplicative scales depends on the research objectives and hypothesized pathophysiological model. The additive scale may be more appropriate for public health prediction, while the multiplicative scale may better suit etiological discovery [1].

Methodological Approaches and Analytical Frameworks

Study Designs for Detecting G×E

Several study designs are available for investigating G×E, each with distinct advantages:

- Family-based studies: Utilize related individuals to control for population stratification but require specialized analytical methods to account for familial correlation [2].

- Case-control studies: Compare genetic and environmental exposures between affected and unaffected individuals.

- Cohort studies: Follow participants over time to observe how genetic and environmental factors interact to influence disease incidence [1].

- Consortium-based meta-analyses: Combine data from multiple studies to achieve the large sample sizes needed for genome-wide interaction analyses [3].

Analytical Methods for Different Data Structures

The appropriate analytical method depends on both study design and data structure:

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Gene-Environment Interaction Studies

| Data Structure | Recommended Methods | Key Considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrelated Individuals | Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) | Robust to correlation structure misspecification | [2] |

| Family Data | Linear Mixed-effects Models (LMM) | Accounts for kinship structure; sensitive to model misspecification | [2] |

| Longitudinal Measures | GEE with small-sample modifications | Controls Type I error with infrequent exposures | [2] |

| Large-scale Consortia | Mendelian Randomization (MR) framework | Detects combined G×E and mediation effects | [3] |

Mendelian Randomization Framework for G×E Detection

A powerful new approach connects G×E detection with the Mendelian randomization (MR) framework, which tests for horizontal pleiotropy to identify interactions [3]. This method compares marginal genetic effects (α) from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with main genetic effects (β₁) from genome-wide interaction studies (GWIS) using the relationship:

α = θβ₁ + (ρσᴇ₁/σɢ₁)β₂ + (μᴇ₁ + ρσᴇ₁/σɢ₁)β₃ [3]

Genetic variants exhibiting significant deviations from the expected relationship based on this model indicate potential G×E. This approach is particularly valuable because it can be applied to existing GWAS and GWIS summary statistics, leveraging the large sample sizes already available from consortia like the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium [3].

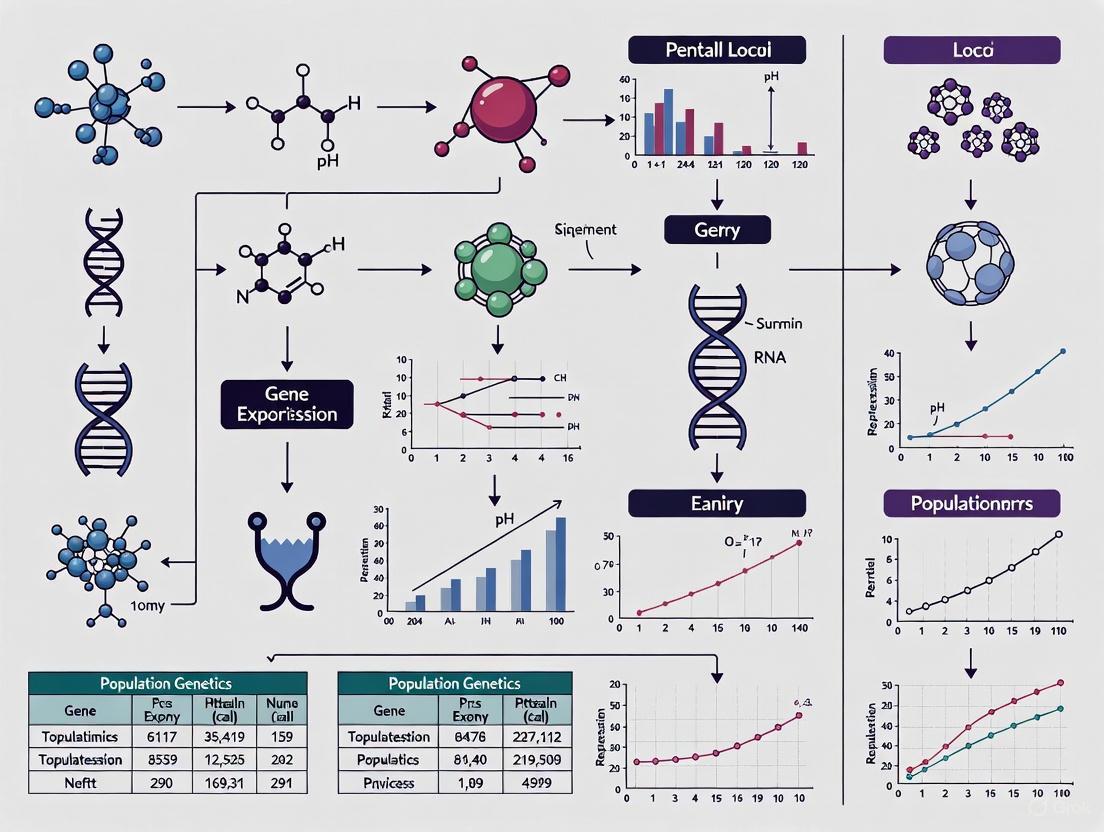

Figure 1: Mendelian Randomization Framework for G×E Detection. This diagram illustrates how the MR approach tests for deviations from expected genetic effects to identify interactions.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Genome-Wide Interaction Study (GWIS) Protocol

A standard protocol for conducting a GWIS involves these key steps:

- Quality Control: Apply standard GWAS QC metrics to genetic data, including call rate, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and imputation quality.

- Environmental Exposure Assessment: Precisely characterize and quantify environmental exposures through questionnaires, biomarkers, or geographic data.

- Covariate Adjustment: Include appropriate covariates such as age, sex, principal components for genetic ancestry, and study-specific factors.

- Model Fitting: For each SNP, fit the interaction model: Y = β₀ + β₁G + β₂E + β₃G×E + ε.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply genome-wide significance threshold (typically p < 5×10⁻⁸) to account for multiple comparisons.

- Meta-Analysis: Combine results across studies using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects or random-effects models.

- Replication: Validate significant findings in independent populations [2] [3].

For family-based studies, the protocol must be modified to account for relatedness using generalized estimating equations (GEE) or linear mixed-effects models (LMM) [2].

Sample Size Considerations and Power

Achieving adequate statistical power is a major challenge in G×E studies. The table below illustrates approximate sample sizes needed to detect interactions of varying effect sizes:

Table 3: Sample Size Requirements for Detecting Gene-Environment Interactions

| Minor Allele Frequency | Exposure Prevalence | Interaction Effect Size | Required Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common (MAF = 0.4) | Common (E = 0.3) | Small | ~50,000 |

| Common (MAF = 0.4) | Common (E = 0.3) | Moderate | ~15,000 |

| Common (MAF = 0.4) | Rare (E = 0.1) | Moderate | ~40,000 |

| Rare (MAF = 0.1) | Common (E = 0.3) | Moderate | ~60,000 |

| Rare (MAF = 0.1) | Rare (E = 0.1) | Large | ~75,000 |

Note: MAF = minor allele frequency; E = exposure prevalence; Effect sizes based on simulation studies from [2]. Sample sizes are approximate and vary based on trait architecture.

Figure 2: Genome-Wide Interaction Study (GWIS) Workflow. This diagram outlines the standard analytical pipeline for G×E detection, from study design through interpretation.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for G×E Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biobanks & Cohorts | Personalized Environment and Genes Study (PEGS), UK Biobank, Framingham Heart Study | Provide DNA samples, extensive phenotyping, and environmental exposure data for discovery and replication [4] [2] |

| Genotyping Arrays | Global Screening Array, UK Biobank Axiom Array | Genome-wide SNP coverage for imputation and association testing |

| Analysis Software | Cytoscape, PLINK, METAL, GECCO | Network visualization, genetic association analysis, meta-analysis, and interaction testing [5] |

| Annotation Databases | Gene Ontology, NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog | Functional annotation of identified loci and biological pathway analysis [5] |

| Consortia | Gene-Lifestyle Interactions Working Group, CHARGE Consortium | Facilitate large-scale meta-analyses through collaborative networks [3] |

The Personalized Environment and Genes Study (PEGS) deserves special mention as it represents a dedicated resource for G×E research, having collected DNA samples from nearly 20,000 participants with in-depth health history and environmental exposure data, with a subset of 5,000 individuals having whole-genome sequencing data [4].

Applications and Future Directions

Biological Insights from G×E Studies

Application of these methods has yielded important biological insights. For example, in a study of serum lipids, researchers identified and confirmed five loci (representing six independent signals) that interacted with either cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption [3]. These findings empirically demonstrated that interaction and mediation are major contributors to genetic effect size heterogeneity across populations.

The estimated lower bound of the interaction and environmentally mediated heritability was significant for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides in cross-population analyses, improving our understanding of the genetic architecture of these important cardiovascular risk factors [3].

Emerging Approaches and Precision Environmental Health

The field is evolving from candidate gene-environment studies to genome-wide interaction studies (GWIS) and incorporating multi-omics data to understand the mechanisms through which environments interact with genetic variation [6]. The concept of precision environmental health (PEH) aims to translate G×E findings into targeted interventions based on an individual's genetic profile and environmental exposures [6].

Future directions include:

- Integration of exposome-wide association studies with genomic data

- Development of advanced statistical methods that leverage biobank-scale data

- Application of G×E findings to clinical practice for personalized risk assessment

- Consideration of ethical implications including environmental justice, return of results, and data privacy [6]

These advances will ultimately enable researchers to move beyond the nature-versus-nurture dichotomy to a more integrated understanding of how genes and environments jointly shape health and disease across natural populations.

Gene–environment interactions (GxE) represent a fundamental concept in evolutionary biology, describing the process by which environmental factors influence the expression of heritable traits and how these traits, in turn, are shaped by natural selection. The impact of the environment on phenotype—encompassing cellular function, physiology, morphology, and behavior—has been recognized for centuries, with phenotypic plasticity identified as a core characteristic of life [7]. Phenotypic plasticity refers to the ability of individual genotypes to produce different phenotypes in response to different environmental conditions [7]. Understanding the genetic architecture of this plasticity remains a central challenge in evolutionary biology, despite decades of research describing GxE [7]. Within natural populations, organisms face both chronic and acute human-induced environmental changes at local and global scales, heightening the urgency to comprehend plastic responses to environmental change and how this plasticity evolves [7].

This framework is powerfully illustrated by two compelling case studies: the convergent evolution of lactase persistence in human populations and the transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of trauma responses. These examples demonstrate how natural selection operates on different mechanisms—from coding region mutations to epigenetic regulation—to shape adaptations in response to culturally and environmentally imposed selection pressures. The following sections explore these phenomena in detail, integrating quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualizations to elucidate the mechanistic bases of these evolutionary echoes.

Case Study I: Lactase Persistence as Gene-Culture Coevolution

Biological Mechanism and Global Distribution

Lactase persistence (LP) provides one of the clearest examples of niche construction and gene–culture coevolution in humans [8]. Biologically, lactase is the enzyme responsible for hydrolyzing lactose, the primary sugar in milk, into absorbable glucose and galactose [8]. In most mammals, including a significant portion of humans, lactase production declines after weaning, a developmental pattern known as lactase non-persistence [8]. However, some human populations exhibit lactase persistence—the continued production of lactase throughout adulthood—enabling them to digest fresh milk without discomfort [9].

The global distribution of lactase persistence reveals striking patterns that correlate with ancestral dairy practices. LP frequency varies widely, from approximately 15-54% in eastern and southern Europe to 62-86% in central and western Europe, and peaks at 89-96% in the British Isles and Scandinavia [8]. Similarly, in India, LP frequency is higher in the north (63%) than in the south (23%) [8]. Across Africa, the distribution is particularly patchy, with high frequencies predominantly found in traditionally pastoralist populations such as the Beni Amir of Sudan (64%), while neighboring non-pastoralist populations show much lower frequencies (~20%) [8]. This distribution pattern provided the initial clue that LP might represent an adaptation to dairy consumption.

Genetic Architecture and Convergent Evolution

Molecular genetic studies have revealed that lactase persistence represents a classic example of convergent evolution, with different genetic mutations arising independently in populations with histories of dairy farming and pastoralism [8].

Table 1: Lactase Persistence-Associated Genetic Variants Across Populations

| Population | Variant Name | Location | Estimated Age (years) | Estimated Selection Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European | rs4988235 (-13910*T) | MCM6 intron | 2,188 - 20,650 [8] | 1.4-19% [8] |

| African | rs145946881 (-14010*C) | MCM6 intron | 1,200 - 23,200 [8] | 1-15% [8] |

| African | rs41525747 (-13907*G) | MCM6 intron | Not specified | Not specified |

| African | rs41380347 (-13915*G) | MCM6 intron | Not specified | Not specified |

All identified LP-associated variants reside in an intron of the MCM6 gene, which neighbors the lactase gene (LCT) [8]. These variants affect lactase promoter activity, thereby influencing the persistence of lactase production into adulthood [8]. The remarkable aspect of this genetic architecture is that all functional variants cluster within the same 100-nucleotide region, yet occur on different haplotypic backgrounds, indicating multiple independent evolutionary origins [8] [9].

The estimated selection coefficients for these alleles range from 1% to an extraordinary 19%, ranking among the highest values reported for any human genes in the last 30,000 years [8]. These estimates suggest intense selective pressure, likely driven by the nutritional advantages of milk consumption in pastoralist societies.

Experimental Protocols for LP Research

Genotyping and Association Studies:

- Sample Collection: Collect DNA from individuals with known lactase persistence status (determined by hydrogen breath test or direct lactase activity measurement).

- Variant Screening: Perform PCR amplification of the MCM6 intronic region containing known LP-associated variants, followed by Sanger sequencing or targeted SNP genotyping.

- Association Analysis: Conduct case-control association studies to correlate genotype with phenotype, calculating odds ratios and population-specific heritability.

- Haplotype Analysis: Determine the haplotype background of LP-associated alleles using flanking markers to establish evolutionary independence across populations.

Functional Validation:

- Luciferase Reporter Assays: Clone DNA sequences containing different LP-associated alleles upstream of a minimal promoter and luciferase reporter gene.

- Transfection: Introduce constructs into cultured intestinal cell lines (e.g., Caco-2).

- Expression Quantification: Measure luciferase activity to determine the effect of each variant on promoter activity.

- Transcription Factor Binding: Perform electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) with nuclear extracts to identify specific transcription factors whose binding is altered by LP-associated variants.

Diagram 1: Gene-Culture Coevolution of Lactase Persistence

Case Study II: Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Trauma

Epigenetic Mechanisms in Trauma Responses

Epigenetics, a term first proposed by Conrad Hal Waddington in the 1940s, refers to stable but reversible changes in gene expression that occur without alterations to the primary DNA sequence [10]. The molecular mechanisms mediating epigenetic regulation include:

DNA Methylation: The covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5' position of cytosine residues within CpG dinucleotides, generally associated with gene silencing, though context-dependent activation is also observed [10].

Histone Modifications: Post-translational modifications including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, which alter chromatin structure and DNA accessibility [10].

Non-Coding RNAs: Regulatory RNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs) that modulate gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [10].

These mechanisms form an interconnected regulatory network that enables cells to adapt to environmental signals while preserving epigenetic memory across cell divisions [10]. Throughout life, the epigenome undergoes dynamic reprogramming, particularly in response to significant environmental exposures such as trauma.

Intergenerational vs. Transgenerational Inheritance

A critical distinction exists between intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic effects:

Intergenerational effects occur when the exposure directly affects multiple generations simultaneously. For maternal exposures during pregnancy, this includes the fetus (F1) and its developing germ cells (the future F2 generation) [10].

Transgenerational inheritance proper manifests in generations never directly exposed to the original environmental trigger (F2 or later for paternal exposures; F3 or later for maternal exposures) [10].

Table 2: Documented Epigenetic Correlates of Trauma Across Generations

| Study Population | Exposure Type | Generational Effect | Epigenetic Changes | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holocaust Survivor Offspring | Extreme trauma | Intergenerational | DNA methylation changes in stress-regulatory genes (FKBP5, NR3C1) [10] | Dysregulated HPA axis, increased PTSD and anxiety risk [10] |

| Dutch Hunger Winter Offspring | Prenatal famine | Intergenerational | Persistent DNA methylation changes in metabolic genes [10] | Altered metabolic parameters, increased cardiometabolic disease risk [10] |

| Animal Models (Rodents) | Predator stress, fear conditioning | Transgenerational | Sperm miRNA expression changes, altered DNA methylation in stress-related genes [10] | Behavioral changes, stress sensitivity in unexposed generations [10] |

The evidence from human studies remains largely correlational, with confounding factors such as parenting behaviors, socioeconomic conditions, and shared environment presenting challenges to establishing direct epigenetic causation [10]. However, animal models provide more controlled evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of trauma responses.

Experimental Protocols for Epigenetic Trauma Research

Human Association Studies:

- Cohort Establishment: Recruit individuals with documented trauma exposure and their descendants, plus appropriately matched controls.

- Epigenome-Wide Analysis: Perform DNA methylation profiling using bisulfite conversion followed by microarray or sequencing (e.g., Illumina EPIC array, WGBS).

- Targeted Validation: Conduct pyrosequencing of candidate loci (e.g., FKBP5, NR3C1) for validation in expanded cohorts.

- Functional Correlates: Link epigenetic marks to endocrine measures (cortisol levels) and psychological assessments (PTSD scales).

Animal Model Experiments:

- Trauma Exposure: Subject male rodents to defined trauma (e.g., unpredictable foot shocks, predator odor).

- Breeding Design: Mate exposed males with naive females to produce F1, then cross F1 to produce F2, F3.

- Behavioral Phenotyping: Test offspring generations for anxiety-like behaviors (elevated plus maze, open field) and learning (fear conditioning).

- Molecular Analysis: Profile sperm DNA methylation (RRBS, WGBS) and non-coding RNA expression in each generation.

- Embryo Transfer: Transplant F2 embryos into naive surrogates to control for in utero effects.

Diagram 2: Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GxE Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Profiling Kits | Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit, EZ DNA Methylation Kit | Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis | Bisulfite conversion and array-based methylation quantification |

| Chromatin Analysis | CUT&Tag Assay Kits, ChIP-seq Kits | Histone modification profiling | Mapping histone marks and transcription factor binding |

| Non-coding RNA Analysis | Small RNA-seq Kits, miRNA Inhibitors/Mimics | ncRNA functional studies | ncRNA profiling and gain/loss-of-function experiments |

| Genotyping Arrays | Global Screening Array, Custom SNP Panels | Population genetic studies | High-throughput variant screening |

| CRISPR Epigenetic Editors | dCas9-DNMT3A, dCas9-TET1 | Targeted epigenetic modification | Locus-specific DNA methylation editing |

| Cell Culture Models | Intestinal Organoids, Neuronal Cell Lines | Functional validation studies | In vitro modeling of gene regulation |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6 Mice, Rat Strains | Transgenerational inheritance studies | Controlled environmental exposure experiments |

Discussion: Implications for Disease Resistance and Therapeutic Development

The examples of lactase persistence and trauma inheritance illustrate how natural selection operates on different timescales and mechanisms to shape GxE interactions. Lactase persistence demonstrates rapid recent adaptation through positive selection on genetic variants, while trauma responses potentially represent maladaptive epigenetic inheritance that persists across generations. For drug development professionals, these evolutionary perspectives offer crucial insights.

First, understanding population-specific genetic adaptations like LP is essential for developing targeted therapies and recognizing differential disease risks and treatment responses across populations. Second, the emerging field of epigenetic therapeutics offers promising avenues for interventions that might reverse maladaptive epigenetic marks associated with trauma. Emerging therapies, including psychedelic-assisted treatments and mind-body interventions, show potential for addressing both psychological and epigenetic aspects of trauma [10].

Furthermore, enriched environments, cultural reconnection, and psychosocial interventions have demonstrated potential to mitigate trauma's impacts within and across generations [10]. This suggests that combining biological interventions with environmental manipulation may represent the most effective strategy for breaking cycles of trauma and promoting resilience.

The study of gene-environment interactions reveals the profound capacity of natural selection to shape human biology across diverse timescales and mechanisms. From the rapid genetic adaptation of lactase persistence to the potential transgenerational epigenetic echoes of trauma, these evolutionary processes continue to influence health and disease in contemporary human populations. Future research integrating evolutionary genetics, epigenetics, and neurobiology will be essential for developing effective, targeted interventions that address both the genetic and environmental components of disease risk, ultimately advancing toward a more comprehensive understanding of human health and resilience.

Epigenetics represents a critical interface between the genome and the environment, comprising molecular processes that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These mechanisms provide a "bridge" through which environmental exposures can produce stable and sometimes heritable changes in gene function. The conceptual framework of epigenetics was first proposed by Conrad Hal Waddington in the 1940s, describing how genes and their products interact with the environment to determine developmental trajectories [11]. Contemporary research has identified several core epigenetic mechanisms that respond to environmental cues, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNAs, and three-dimensional genome organization [11] [12].

The dynamic nature of the epigenome allows for both flexibility and memory in gene regulation. Throughout life, epigenetic marks are continuously remodeled in response to environmental influences while maintaining cell type-specific gene expression patterns [11]. This plasticity is particularly evident during critical developmental windows, such as embryogenesis, when extensive epigenetic reprogramming occurs [12]. Environmental exposures during these sensitive periods can induce epigenetic changes that persist throughout the lifespan and may be transmitted to subsequent generations, representing a biological mechanism for the long-term effects of environmental experiences [11] [12].

Core Epigenetic Mechanisms

DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5' position of cytosine residues, primarily within CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [11]. This modification is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and typically associates with transcriptional repression when occurring in promoter regions [13] [12]. DNMT1 maintains existing methylation patterns during cell division, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish new methylation patterns during development and in response to environmental stimuli [12].

The methylation process is dynamic and reversible. Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes catalyze the oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and further oxidation products, initiating active demethylation pathways [11]. Notably, 5hmC is now recognized as an independent epigenetic mark with distinct roles in gene regulation, particularly enriched in neuronal tissues and associated with active transcription [11].

Environmental Influences: DNA methylation patterns are shaped by a complex interplay of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Twin studies estimate that genetic factors explain approximately 5-19% of variance in DNA methylation across most genomic sites, with higher heritability at loci with intermediate methylation levels [13]. Environmental exposures—including diet, toxins, stress, and lifestyle factors—contribute significantly to methylation variation, particularly during developmental windows when the epigenome is most plastic [13] [12].

Histone Modifications and Chromatin Organization

Histone proteins provide structural support for chromosomal DNA and undergo numerous post-translational modifications that influence chromatin accessibility and gene expression. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and newer discoveries such as malonylation, crotonylation, and lactylation [11]. These chemical groups are added to or removed from specific amino acid residues on histone tails by specialized enzymes (e.g., histone acetyltransferases/deacetylases, methyltransferases/demethylases) [12].

The combinatorial pattern of histone modifications constitutes a hypothesized "histone code" that determines transcriptional states by altering DNA-histone interactions and recruiting chromatin-associated proteins [11]. For example, histone acetylation generally associates with open, transcriptionally active chromatin, while certain methylation marks (e.g., H3K27me3) correlate with transcriptional repression [12].

Three-Dimensional Genome Architecture: Beyond chemical modifications, the spatial organization of chromatin within the nucleus represents another layer of epigenetic regulation. The proximity of genes to regulatory elements and their positioning within nuclear compartments significantly influences expression patterns [12]. Both DNA methylation and histone modifications contribute to establishing and maintaining three-dimensional genome architecture [12].

Non-Coding RNAs

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) represent a diverse class of functional RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and epigenetic levels without being translated into proteins [11]. Key categories include microRNAs (miRNAs), which typically bind complementary sequences in target mRNAs to promote degradation or translational inhibition; long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which can regulate chromatin architecture and serve as scaffolds for chromatin-modifying complexes; and circular RNAs (circRNAs), which function as miRNA sponges and interact with RNA-binding proteins [11].

These ncRNAs are essential for normal development and cellular function, and their dysregulation contributes to various diseases [11]. They participate in complex regulatory networks with other epigenetic mechanisms—for instance, certain lncRNAs recruit histone-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, while DNA methylation can influence ncRNA expression [11].

Environmental Exposures and Epigenetic Alterations

Environmental factors can induce epigenetic changes that potentially influence disease susceptibility and health outcomes across generations. The following table summarizes key exposure categories and their documented epigenetic effects.

Table 1: Environmental Exposures and Associated Epigenetic Alterations

| Exposure Category | Specific Exposures | Documented Epigenetic Changes | Biological/Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Stress | Childhood trauma, chronic stress, PTSD | Altered DNA methylation of stress-response genes (FKBP5, NR3C1); histone modifications in limbic brain regions [11] [14] | Dysregulated HPA axis; increased risk of psychiatric disorders; cognitive impairments [11] [14] |

| Toxic Substances | Heavy metals (arsenic, lead, cadmium), air pollutants (PM, benzene), endocrine disruptors | DNA methylation changes in immune/metabolic genes; histone modifications; global methylation alterations [15] [13] [16] | Neurodevelopmental deficits; immune dysfunction; metabolic syndrome; accelerated aging [15] [16] [17] |

| Nutritional Factors | Dietary methyl donors (folate, choline, B vitamins), high-fat diet, malnutrition | Altered DNA methylation of metabolic genes; persistent changes at metastable epialleles; histone modifications [13] [12] | Altered metabolism; increased disease risk; transgenerational effects [13] [12] |

| Lifestyle Factors | Smoking, alcohol, exercise, sleep patterns | Genome-wide DNA methylation changes; gene-specific methylation; histone modifications in tissues [13] | Addiction; metabolic diseases; cancer; inflammatory conditions [13] |

Intergenerational vs. Transgenerational Inheritance

A critical distinction exists between intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Intergenerational effects occur when the offspring (F1 generation) is directly exposed to the environmental factor through parental exposure, such as maternal smoking during pregnancy affecting the fetus (F1) and its germ cells (future F2) [11]. Transgenerational inheritance proper requires manifestations in generations without direct exposure (F3 or later for maternal exposures, F2 or later for paternal exposures) [11].

In mammals, establishing transgenerational inheritance is methodologically challenging because it requires that epigenetic changes escape two waves of comprehensive epigenetic reprogramming—during primordial germ cell development and early embryogenesis [11] [12]. While well-documented in plants and invertebrates, evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals remains an area of active investigation and debate [11].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Model Organisms and Study Designs

Research on environmental epigenetics employs diverse model systems, each offering distinct advantages. Murine models permit controlled environmental manipulations and multigenerational tracking in a mammalian system with well-characterized genetics [11] [12]. Epidemiological studies in humans examine associations between ancestral exposures and epigenetic marks in descendants, though establishing causality is challenging due to confounding variables [11]. Birth cohorts with biological sample banks and exposure records enable prospective studies linking early-life exposures to lifelong epigenetic trajectories [15] [12].

Table 2: Key Methodological Approaches in Environmental Epigenetics

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenome Profiling | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS), ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, methylation arrays | Genome-wide mapping of DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility | Cost, coverage, resolution; cell-type specificity requires pure populations or deconvolution algorithms [12] |

| Multi-omics Integration | Combined DNA methylation, transcriptome, metabolome profiling on same samples | Uncovering mechanistic links between exposure, epigenetic changes, and functional outcomes | Computational complexity; requires specialized statistical approaches [15] [6] |

| Exposure Assessment | Questionnaires, environmental monitoring, geographic information systems (GIS), biomonitoring, epigenetic fingerprinting | Quantifying environmental exposures; reconstructing past exposures using epigenetic signatures [15] [18] | Recall bias; exposure misclassification; complex mixture effects |

| Germline Epigenetics | Sperm and oocyte epigenetic profiling, preimplantation embryo analysis | Direct assessment of epigenetic information transmitted through gametes [11] [12] | Technical challenges of low input material; ethical considerations in human studies |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Multigenerational Epigenetic Effects

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for investigating transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in a murine model, adaptable for studying various environmental exposures:

1. Exposure Paradigm and Breeding Scheme:

- F0 Generation: Expose adult male and female mice to the environmental factor (e.g., specific toxicant, stress paradigm, dietary intervention) for a defined period before mating. Include appropriate control groups.

- F1 Generation: Generate two types of F1 offspring—directly exposed (via in utero exposure if maternal exposure continues) and indirectly exposed (through paternal germline only). Cross F1 animals with unexposed partners to produce F2 generation.

- F2 and F3 Generations: Continue breeding each generation with unexposed partners to distinguish intergenerational (F2) from true transgenerational (F3) effects, as the F3 generation is the first completely unexposed.

2. Tissue Collection and Processing:

- Collect relevant tissues (e.g., brain regions, liver, blood) at consistent developmental time points across generations.

- Isolate germ cells (sperm/oocytes) at specific developmental stages to assess epigenetic marks in gametes.

- Process samples for multiple molecular analyses, including DNA/RNA extraction, chromatin preparation, and histology.

3. Epigenetic Analysis:

- Perform DNA methylation analysis using WGBS or RRBS on germ cells and somatic tissues across generations.

- Conduct histone modification profiling via ChIP-seq for key marks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9ac) in tissues of interest.

- Analyze ncRNA expression in germ cells and plasma using small RNA-seq.

4. Functional Validation:

- Correlate epigenetic changes with transcriptomic data (RNA-seq) from matching tissues.

- Employ epigenetic editing (e.g., CRISPR-dCas9 systems targeting DNMTs/TETs or histone modifiers) to validate causal relationships between specific epigenetic marks and phenotypic outcomes.

- Conduct behavioral, metabolic, or physiological assessments to link molecular changes to functional phenotypes.

5. Data Integration and Statistics:

- Implement appropriate statistical models that account for litter effects, sex differences, and multiple comparisons.

- Use bioinformatic approaches to integrate epigenomic, transcriptomic, and phenotypic data.

- Apply pathway analysis to identify biological processes affected by transgenerational epigenetic changes.

Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Environmental Epigenetics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical treatment that converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, enabling detection of methylation status | EZ DNA Methylation kits (Zymo Research), MethylCode Bisulfite Conversion Kit (Thermo Fisher) - essential for WGBS, RRBS, and array-based methylation analysis |

| DNMT/HDAC Inhibitors | Chemical inhibitors that block DNA methyltransferase or histone deacetylase activity, used to experimentally manipulate epigenetic states | 5-azacytidine (DNMT inhibitor), Vorinostat/Trichostatin A (HDAC inhibitors) - tools for establishing causal relationships between epigenetic marks and gene expression |

| Epigenetic Antibodies | Target-specific antibodies for immunoprecipitation or visualization of epigenetic marks | Anti-5-methylcytosine, anti-H3K27me3, anti-H3K9ac - required for ChIP-seq, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry applications |

| Single-Cell Multi-omics Platforms | Technologies enabling simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers from single cells | 10x Genomics Multiome (ATAC + gene expression), single-cell bisulfite sequencing - resolves cell-type-specific epigenetic changes in heterogeneous tissues |

| Epigenetic Editing Systems | CRISPR-based tools for targeted manipulation of specific epigenetic marks at defined genomic loci | dCas9-DNMT3A/TET1 fusion constructs, dCas9-p300 - enables functional validation of epigenetic changes without altering DNA sequence |

| Methylation Arrays | Microarray platforms for cost-effective profiling of DNA methylation at predefined genomic sites | Illumina EPIC array (850,000 CpG sites) - widely used in human epidemiological studies for epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Workflows

Figure 1: Environmental Exposures Trigger Epigenetic Changes That Influence Health Outcomes Across Generations. This pathway illustrates how diverse environmental factors converge on biological processes that modify epigenetic regulation, leading to altered gene expression and potentially heritable health effects.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Transgenerational Epigenetics Research. This workflow outlines key methodological stages for investigating how environmental exposures induce epigenetic changes that may be inherited across generations.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The field of environmental epigenetics continues to evolve with several promising research directions emerging. Precision Environmental Health represents a paradigm shift that integrates genetics, environmental exposure data, and multi-omics measurements to understand individual susceptibility and develop targeted prevention strategies [18] [6]. This approach moves beyond traditional "one exposure at a time" studies to embrace the exposome framework—a more holistic assessment of all environmental exposures throughout the lifespan and their corresponding biological responses [18].

Emerging Therapeutic Approaches that target epigenetic mechanisms offer promising avenues for intervention. Psychedelic-assisted treatments, mind-body interventions, and enriched environments have shown potential to address both psychological and epigenetic aspects of trauma [11]. Similarly, epigenetic editing technologies provide tools for precise manipulation of epigenetic marks to establish causal relationships and explore therapeutic applications [16].

Methodological Innovations in multi-omics integration, single-cell epigenomics, and computational modeling are advancing the field's capacity to decipher complex gene-environment interactions [15] [6]. Extracellular vesicles are emerging as promising tools for non-invasive assessment of tissue-specific epigenetic changes, potentially enabling "liquid biopsies" for environmental health monitoring [18].

The evidence supporting environmentally induced epigenetic changes continues to grow, but significant challenges remain in establishing causal relationships and understanding the extent of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in human populations. Future research will need to address methodological limitations, account for confounding variables, and develop ethical frameworks for translating these findings into effective public health interventions and personalized prevention strategies [11] [12]. By integrating biological, social, and cultural perspectives, the field moves closer to understanding how environmental experiences become biologically embedded and how to potentially mitigate negative health impacts across generations.

Gene-environment interactions (G × E) refer to phenomena where the effect of a genetic variant on a phenotype depends on an individual's exposure to specific environmental factors, and vice versa. Statistically, this is represented as a deviation from the expected combined effect of genetic and environmental factors acting alone [19]. The investigation of G × E is crucial for understanding the "missing heritability" in complex traits—the gap between broad-sense heritability estimates from family studies and the narrow-sense heritability attributable to identified genetic variants [19]. For autism spectrum disorder (ASD), while heritability estimates reach up to 80%, solely genetic causes account for only 10-30% of cases, creating a substantial etiological gap that G × E research aims to fill [20] [21]. Furthermore, the dramatic increase in ASD prevalence over recent decades cannot be fully explained by diagnostic substitution alone, suggesting environmental factors interact with genetic susceptibilities [20]. This case study examines ASD as a model condition for understanding G × E dynamics, with particular focus on metabolic dysregulation as a key interface where genetic and environmental influences converge.

Autism Spectrum Disorder: A G×E Case Study

Genetic Architecture and Environmental Risk Landscape

ASD presents a clinically and etiologically heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition characterized by core deficits in social communication and restrictive, repetitive behaviors [20] [21]. Its genetic architecture involves hundreds of genes operating through diverse mechanisms, including rare inherited or spontaneous mutations with large effects (e.g., copy number variants at 16p11.2 or mutations in CHD8, SHANK3) and common variants of small effect that exert additive influences in a polygenic manner [21]. Twin studies indicate that environmental factors contribute approximately 40-60% of the variance in ASD susceptibility [20] [21].

Environmental factors associated with ASD risk include advanced parental age, maternal autoimmune conditions, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, infection during pregnancy, perinatal complications, and prenatal exposure to environmental chemicals such as air pollutants, pesticides, and certain medications [20] [21]. The developing brain is particularly vulnerable to these environmental insults during critical neurodevelopmental windows.

Table 1: Key Environmental Factors Associated with ASD Risk

| Environmental Factor Category | Specific Examples | Proposed Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Health Factors | Advanced parental age, autoimmune disease, obesity, diabetes, hypertension | Inflammation, oxidative stress, epigenetic modifications [21] |

| Medications/Teratogens | Valproic acid, thalidomide, misoprostol | Epigenetic changes, endocrine disruption, altered neural migration [22] |

| Environmental Chemicals | Air pollutants (PM, NO₂, PAHs), pesticides, BPA, phthalates, PCBs, heavy metals | Oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, endocrine disruption, hypoxic damage [20] [22] |

| Perinatal Factors | Prematurity, obstetric complications, neonatal hypoxia | Mediation of maternal factors, direct injury to developing brain [21] |

Mechanistic Insights: Biological Pathways of G×E Convergence

G × E in ASD converges on several core pathophysiological mechanisms, with metabolic and immunologic pathways representing major interfaces.

Metabolic Dysregulation

Metabolic disturbances are increasingly recognized as central to ASD pathophysiology. A recent Mendelian randomization study identified 55 known blood metabolites and 13 metabolite ratios significantly associated with ASD, highlighting tryptophan metabolism as the most notable disrupted pathway [23]. Specific metabolites implicated include dodecenedioate, methionine sulfone, and the cysteine-to-alanine and proline-to-glutamate ratios [23]. These findings point to disruptions in cellular glucuronidation, glucuronosyltransferase activity, bile secretion, and apical cellular functions [23].

Brain energy metabolism is particularly crucial, with studies demonstrating mitochondrial dysfunction characterized by impaired oxidative phosphorylation, elevated lactate and alanine levels, carnitine deficiency, abnormal reactive oxygen species production, and altered calcium homeostasis [24]. These disturbances are especially impactful in high-energy brain regions like the precuneus, which serves as an integrative default mode network hub and shows both functional and structural abnormalities in ASD [24].

The following diagram illustrates the core pathway through which genetic mutations in synaptic genes lead to neurometabolic alterations and neuronal dysfunction in ASD, integrating findings from genetic and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies:

Diagram 1: Genetic variants to ASD behaviors pathway

Immune and Inflammatory Pathways

Immune dysregulation represents another major pathway for G × E in ASD. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal significant upregulation of immune-related genes coupled with disruptions in amino acid and lipid metabolism [25]. Key transcription factors identified in this dysregulation include RARA, NFKB2, and ETV6, which regulate the expression of genes involved in immune responses and pro-inflammatory cytokine production [25]. These immune alterations interact with metabolic pathways, creating a vicious cycle of neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction.

The following table summarizes key molecular profiles identified through multi-omics studies in ASD:

Table 2: Multi-Omics Profile in ASD from Integrated Studies

| Molecular Layer | Key Alterations | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | 85 upregulated genes (immune activation); 33 downregulated genes (synaptic function) | Increased neuroinflammation; impaired synaptic transmission and plasticity [25] |

| Metabolomics | 13 upregulated, 2 downregulated metabolites; altered amino acid/lipid metabolism | Disrupted cellular energetics; substrate availability for neurotransmission [25] |

| Pathway Convergence | Antigen processing/presentation; nuclear-cytoplasmic transport; cytokine signaling | Altered immune surveillance; disrupted cellular communication [25] |

Xenobiotic Response Systems

Genes involved in detoxification pathways and physiological barrier function regulate individual susceptibility to environmental xenobiotics. An analysis of ASD datasets identified 77 XenoReg genes with predicted damaging variants, including 47 genes encoding detoxification enzymes and 30 genes involved in physiological barrier function [22]. These include highly polymorphic genes such as CYP1A2, ABCB1, ABCG2, GSTM1, and CYP2D6, which interact with ubiquitous xenobiotics including benzo-(a)-pyrene, valproic acid, bisphenol A, particulate matter, methylmercury, and perfluorinated compounds [22].

Individuals carrying damaging variants in these genes likely have less efficient detoxification systems or impaired physiological barriers (blood-brain barrier, placenta, respiratory epithelium), making them particularly vulnerable to early-life exposure to neurotoxicants during critical windows of brain development [22]. These exposures can trigger neuropathological mechanisms including epigenetic changes, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, hypoxic damage, and endocrine disruption [22].

Methodological Approaches for G×E Investigation

Analytical Frameworks and Study Designs

G × E research employs diverse analytical frameworks tailored to specific research questions and available data. Key approaches include:

- Genome-Wide Interaction Studies (GWIS): Test for interactions between environmental factors and genetic variants across the genome, typically using linear regression with an interaction term [19] [3].

- Mendelian Randomization (MR): Uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to assess causal relationships between exposures and outcomes, with recent extensions to test G × E [23] [3].

- Case-Only Designs: Estimate G × E under the assumption of gene-environment independence, offering greater efficiency for rare diseases [19].

- Polygenic Score × Environment (PGS×E): Examines how environmental factors modify the effects of aggregate genetic risk scores on traits [19].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a two-sample Mendelian randomization study, an approach used to identify causal relationships between blood metabolites and ASD:

Diagram 2: Mendelian randomization workflow

Integrated Omics Approaches

The combination of multiple omics technologies provides powerful insights into G × E mechanisms. For example:

- Combined Transcriptomics-Metabolomics: Integration of gene expression data with metabolic profiles can reveal how genetic susceptibilities translate into functional phenotypic alterations through metabolic rearrangements [25].

- Imaging Genetics: The combination of neuroimaging (e.g., 1H-MRS) with genetic analysis allows investigation of how genetic variants affect brain metabolism and neurochemistry [26]. One study integrated genetic variants in neurotransmission and synaptic genes with 1H-MRS data, finding that ASD patients with predicted damaging variants showed lower levels of total creatine and total N-acetyl aspartate, markers of bioenergetics and neuronal metabolism, respectively [26].

Statistical Considerations and Challenges

G × E studies face several methodological challenges, including inadequate statistical power due to the enormous multiple testing burden, difficulty in accurately measuring environmental exposures, confounding by population stratification, and collinearity between genetic and interaction terms in regression models [19] [3]. Novel approaches are emerging to address these challenges, including methods that leverage the connection between Mendelian randomization and G × E testing [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for G×E Studies in ASD

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | Autism Genome Project (AGP); Autism Sequencing Consortium (ASC); gnomAD; Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) | Genetic variant discovery; control population frequencies; large-scale genetic association data [26] [23] |

| Analytical Tools | Two-sample MR; IVW, MR-Egger methods; Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA); Ensemble Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | Causal inference; network-based transcriptomics; functional prediction of genetic variants [23] [25] [26] |

| Metabolomic Resources | Canadian Longitudinal Study of Aging (CLSA) metabolomics data; Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) | Metabolite quantitative trait loci; chemical-gene interaction data [23] [22] |

| Animal Models | BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J mouse model; Mecp2, Shank3, Ube3a mutant models | Study of metabolic, behavioral, and neurobiological phenotypes; testing therapeutic interventions [24] [21] |

| Pathway Analysis | KEGG; Gene Ontology; Reactome; SynaptomeDB | Biological pathway enrichment; functional annotation of gene sets [25] [26] |

The investigation of gene-environment interactions in ASD reveals a complex landscape where genetic susceptibilities modulate individual responses to environmental exposures, and environmental factors influence the expression of genetic risks. Metabolic pathways serve as a crucial interface where these interactions converge, with disruptions in mitochondrial function, neurotransmitter metabolism, and immunometabolic crosstalk contributing to disease pathophysiology.

Future research directions should include: (1) larger sample sizes with deep phenotyping to enhance statistical power; (2) longitudinal designs to capture dynamic G × E across development; (3) integration of multi-omics data to elucidate biological mechanisms; (4) development of advanced analytical methods to detect subtle interactions; and (5) translation of G × E findings into personalized prevention strategies for environmentally susceptible genetic subgroups [19] [6] [22]. Understanding these complex interactions will ultimately enable more precise diagnostic approaches and targeted interventions for ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Advanced Tools and Translational Applications: From Multi-Omics to Clinical Breakthroughs

The field of genomics has undergone a profound methodological transformation, moving from cataloguing simple genetic associations to untangling the complex interplay between genes and environmental factors. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) marked the first major paradigm, successfully identifying thousands of genetic variants linked to traits and diseases. However, their limitation in explaining the "missing heritability" and accounting for environmental context spurred the development of gene-environment interaction (GxE) analyses. Initially, these were constrained to candidate genes due to computational limitations. The emergence of genome-wide interaction studies (GWIS) and dedicated GxE frameworks represents the current frontier, enabling unbiased discovery at scale. This evolution is crucial for natural population research, where genetic effects are not static but are shaped and modified by a myriad of environmental exposures, paving the way for true precision medicine and public health interventions [27] [4].

The Foundational Era of Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

Core Principles and Landmark Achievements

The GWAS approach, catalyzed by landmark studies around 2005-2007, tests hundreds of thousands to millions of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome for association with a specific trait or disease, without prior hypothesis about biological function. The fundamental output is the identification of genomic loci significantly associated with phenotypic variation. This methodology rests on the principle of linkage disequilibrium (LD), allowing genotyped tags SNPs to serve as proxies for ungenotyped causal variants.

The success of GWAS is undeniable. Over the past two decades, thousands of GWAS have been published, uncovering tens of thousands of loci for human traits ranging from common diseases like cardiovascular conditions to unconventional traits such as family income [27]. These studies have provided profound biological insights, validated the highly polygenic nature of most complex traits, and have directly informed drug discovery. Notable examples include the identification of:

- PCSK9 as a target for lipid-lowering therapies (discovered just before the GWAS era) [27].

- CYP2C19 polymorphisms affecting clopidogrel metabolism, leading to genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy [27].

- IL6R variants linked to C-reactive protein levels, motivating trials of IL6R antagonists [27].

Inherent Limitations and the Drive for Advancement

Despite these successes, foundational challenges with GWAS became apparent, driving the need for more sophisticated analytical frameworks.

Table 1: Persistent Obstacles in Traditional GWAS

| Obstacle | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Technological Inertia | Slow adoption of new genomic references (e.g., T2T, pangenome) beyond older builds like GRCh37. | Restricted genomic resolution and inaccurate representation of structural variants and diversity [27]. |

| LD Bottleneck | Reliance on massive, population-specific LD matrices for imputation and analysis. | Computationally burdensome and limits portability and scalability, especially in diverse populations [27]. |

| Heritability over Actionability | Focus on explaining phenotypic variance at the population level. | Limited translational value for clinical decision-making or individual-level risk prediction [27]. |

| Lack of Diversity | Over 80% of GWAS participants are of European ancestry. | Limited generalizability, equity, and failure to capture population-specific biology [27] [28]. |

A stark reality check was the 2025 bankruptcy of 23andMe, which served as a reminder of the limited translational value of GWAS findings and polygenic risk scores (PRS) for the general public [27]. Furthermore, while a GWAS for height identified over 12,000 independent SNPs, the practical, actionable insights from such a discovery remain limited [27]. These limitations underscored that genetics alone is insufficient; context is key, propelling the field toward interaction analyses.

The Rise of Gene-Environment Interaction (GxE) Analyses

Conceptual Framework and Biological Significance

GxE analysis investigates how genetic and non-genetic factors interplay to influence complex traits. It posits that the effect of a genetic variant on a phenotype is dependent on an individual's exposure to a specific environmental factor, and vice-versa. This framework is biologically grounded in the understanding that environmental exposures can regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself, primarily through epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modification [29] [14].

This interaction is fundamental to understanding behavior, disease risk, and treatment response. For instance, the Diathesis/Stress model in psychiatry provides a framework where genetic vulnerabilities (diatheses) interact with environmental stressors to trigger mental health disorders [14]. Epigenetics serves as the mechanistic link, with studies showing that experiences like chronic social defeat stress can alter DNA methylation profiles in male germ cells in mice, suggesting a pathway for the transgenerational inheritance of environmentally acquired traits [29] [14].

Methodological Evolution: From Candidate GxE to Genome-Wide Interaction Studies (GWIS)

The initial approach to GxE was candidate-based, focusing on pre-specified genetic variants in biologically plausible pathways. While informative, this method was inherently restricted by prior knowledge and failed to discover novel interactions.

The field subsequently advanced to genome-wide interaction studies (GWIS), which test for interactions across the entire genome, analogous to GWAS. A key application has been in exploring how genetic effects change over the life course. For example, a 2025 GWIS on cardiometabolic risk factors in over 270,000 individuals identified that the effect of specific genetic variants (e.g., rs429358 tagging APOE4) on apolipoprotein B and triglycerides significantly changes with age, with effect sizes generally moving toward the null as people get older [30]. This demonstrates the importance of modeling age as a key environmental modifier.

However, GWIS and early GxE methods faced significant hurdles:

- Massive Sample Size Requirements: Detecting interactions typically requires larger samples than detecting marginal genetic effects [31].

- Computational Intensity: Early methods involved fitting full models across the genome, which was prohibitive for large-scale biobanks [31].

- Trait Limitation: Most early scalable methods were designed only for quantitative or binary traits, leaving out richer data types like time-to-event or ordinal traits [31].

- Population Stratification: Failure to properly account for diverse ancestries and admixture could lead to inflated false-positive rates [31] [28].

State-of-the-Art Frameworks for Genome-Wide Interaction Analysis

The limitations of earlier methods have spurred the development of next-generation computational frameworks designed for the scale and complexity of modern biobank data.

The SPAGxECCT Framework and Its Derivatives

A leading example of modern GxE methodology is the SPAGxECCT framework, introduced in 2025. This framework is designed for scalability and accuracy across diverse trait types in large-scale cohorts [31] [32].

Core Workflow of SPAGxECCT: The method employs a two-step, retrospective approach that considers genotype as a random variable, making it robust to model misspecification.

Diagram 1: The SPAGxECCT analytical workflow. Its two-step process and hybrid p-value calculation ensure efficiency and accuracy.

A key innovation is its use of a hybrid strategy for p-value calculation, combining normal approximation with saddlepoint approximation (SPA). This is particularly crucial for obtaining accurate results when analyzing low-frequency variants or traits with highly unbalanced distributions (e.g., a rare disease) [31].

Advanced Extensions for Complex Data Structures

The SPAGxECCT framework has been extended to address specific analytical challenges:

- SPAGxEmixCCT: This extension accounts for population stratification and is applicable to multi-ancestry or admixed populations. It can be further refined to SPAGxEmixCCT-local, which uses local ancestry information to identify ancestry-specific GxE effects [31].

- SPAGxE+: This extension incorporates a genetic relationship matrix (GRM) to effectively control for sample relatedness within the analysis [31].

These methods represent a significant power advance over approaches that simply include principal components as covariates, as they more directly model the complex patterns of ancestry that can confound GxE analyses.

Application in Complex Trait Analysis: A Case Study on CRC

The power of genome-wide GxE analysis is exemplified by a 2025 study exploring pathways for colorectal cancer (CRC) risk. This research conducted genome-wide interaction analyses for 15 environmental exposures (e.g., BMI, physical activity, processed meat intake). It used advanced statistical methods like the adaptive combination of Bayes Factors (ADABF) and over-representation analysis (ORA) to find pathways enriched for GxE effects [33].

The study identified 1,227 genes within enriched pathways, 50% of which mapped to established hallmarks of cancer, most notably "Sustaining Proliferative Signalling." This approach provided a basis for elucidating the etiology behind risk factor associations and for informing personalized prevention strategies for CRC [33].

Conducting robust genome-wide interaction studies requires a suite of methodological tools, computational resources, and biological data.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Genome-Wide Interaction Analysis

| Category / Resource | Function / Description | Application in GxE |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Software | ||

| SPAGxECCT/SPAGxEmixCCT [31] | Scalable framework for GxE analysis of diverse traits (binary, time-to-event, ordinal) in large biobanks. | Primary analysis of GxE effects, especially for low-frequency variants and in multi-ancestry populations. |

| GEM (Gene-Environment Interaction Analysis) [30] | A tool for performing GWIS, used in studies of age-interaction on cardiometabolic traits. | Testing for interaction effects between genetic variants and specific environmental exposures like age. |

| PLINK Epistasis Module [34] | Performs logistic regression for genome-wide SNP-SNP interaction (epistasis) analysis. | Exploring genetic epistasis, as used in studies of colorectal cancer recurrence. |

| Data Resources | ||

| Large-scale Biobanks (e.g., UK Biobank [31] [30]) | Cohorts with genetic, phenotypic, and environmental data from hundreds of thousands of participants. | Provides the necessary sample size and rich data for well-powered GxE discovery. |

| Open Targets Platform (OTP) [33] | Integrates evidence on gene-disease associations from genetics, genomics, and drugs. | Prioritizing genes identified in GxE studies based on existing biological evidence. |

| PEGS Study [4] | The NIEHS Personalized Environment and Genes Study, merging genetics with detailed health/exposure history. | A resource specifically designed for deep GxE investigation across a range of common diseases. |

| Methodological Concepts | ||

| Saddlepoint Approximation (SPA) [31] | A statistical technique for accurate p-value calculation when distribution is skewed or sample is small. | Critical for controlling type I error rates when testing low-frequency variants or in unbalanced case-control studies. |

| Cauchy Combination Test (CCT) [31] | A method for combining p-values from multiple related tests. | Used in SPAGxEmixCCT to combine evidence from global and local ancestry interaction tests. |

Experimental Protocols for Genome-Wide GxE Analysis

Implementing a genome-wide GxE study involves a structured pipeline from quality control to functional validation. The following protocol outlines the key steps for a typical analysis using a framework like SPAGxEmixCCT.

Diagram 2: End-to-end GxE analysis workflow, from data preparation to biological interpretation.

Phase 1: Data Preparation and Quality Control (QC)

- Genotype & Phenotype Data: Start with quality-controlled genetic data (e.g., imputed dosages) and precisely defined phenotypes (binary, quantitative, time-to-event, or ordinal).

- Quality Control (QC): Apply stringent QC to genetic data. For SNPs, this includes filters for call rate (e.g., >98%), minor allele frequency (MAF) (threshold depends on sample size, e.g., >0.01), and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE p-value > 1x10⁻⁶). Remove individuals with excessive missingness or heterozygosity. For GxE, special attention must be paid to the accurate measurement of the environmental exposure [34] [28].

- Covariate Selection: Define covariates to adjust for potential confounding. These typically include age, genetic sex, and genetic principal components (PCs) to account for population stratification. In admixed populations, local ancestry may be a necessary covariate [31] [30].

Phase 2: Model Fitting and Genome-wide Scan

- Fit Covariates-Only Model: Using a framework like SPAGxECCT, fit a null model that includes the environmental factor of interest and all covariates, but no genotypes. This step is performed only once for the entire genome scan and yields the model residuals [31].

- Genome-wide Scan (GxE): For each SNP, test the GxE term using a score test that projects out the marginal genetic effect from the interaction term to avoid collinearity. Use SPA-based methods for accurate p-value calculation, especially for variants with MAF < 0.01 [31].

- Significance Thresholding: Account for multiple testing. While a standard genome-wide significance threshold is p < 5x10⁻⁸, some studies applying Bonferroni correction for testing multiple traits may use a more stringent threshold (e.g., p < 1x10⁻⁸ for five traits) [30].

Phase 3: Validation and Biological Interpretation

- Replication and Functional Look-up: Seek independent replication of top GxE hits in a separate cohort. For validated signals, use public resources like the Open Targets Platform and functional genomic databases to assess prior evidence and potential mechanisms [33].

- Pathway and Enrichment Analysis: Input the list of genes from significant GxE loci into pathway analysis tools (e.g., FUMA, GOrilla) to identify over-represented biological processes, molecular functions, and hallmarks of cancer, as demonstrated in the CRC GxE study [33] [30].

Future Directions and Translational Challenges

The trajectory of genome-wide interaction analysis points toward greater integration and personalization. A major frontier is the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning models. These could potentially learn complex LD patterns and generate necessary matrices without explicit enumeration, overcoming a major computational bottleneck [27]. Furthermore, there is a push to move beyond explaining heritability and toward evaluating actionability, shifting the focus to how discoveries can directly inform clinical decisions and public health strategies [27].

The expansion of diverse cohorts is both a scientific and moral imperative. Initiatives like the Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) consortium are critical for ensuring that the benefits of genomic research are equitably distributed and for uncovering population-specific biological interactions that remain invisible in Eurocentric studies [28]. The ultimate translation of these findings will be in precision medicine, where an individual's unique genetic and environmental profile can inform tailored prevention strategies and therapeutic interventions, particularly in areas like mental health [14]. Deconvoluting this complex interplay will require not just genetic data, but also integrated epigenetic profiles that capture a "memory" of environmental exposures, potentially leading to tools like an "epigenetic score metre" for disease risk [14].

The molecular processes underlying human health and disease are highly complex, arising from intricate interactions between genetic predispositions and environmental exposures [35]. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, and mental health disorders pose a significant global health challenge, accounting for the majority of fatalities and disability-adjusted life years worldwide [36]. These conditions originate from the dynamic interplay between an individual's largely static genetic code and responsive molecular layers that react to environmental changes, representing key mechanisms through which gene-environment (G×E) interactions manifest [36].

Multi-omics technologies provide a powerful framework for systematically investigating these complex interactions by integrating data across multiple biological layers [37]. This integration encompasses molecular profiles from the genome, epigenome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, lipidome, and microbiome—collectively referred to as multi-omics—along with environmental exposures known as the exposome [36]. Rapid advancements in computational methodologies and high-throughput technologies have made the integration of these diverse datasets increasingly feasible, generating comprehensive biological data at an unprecedented scale [36]. This multi-omics approach enables researchers to move beyond studying individual biological components in isolation toward a holistic understanding of how these systems interact across multiple molecular levels in response to environmental challenges [37].

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies for Studying G×E Interactions

| Omics Layer | Analytical Focus | Key Technologies | Relevance to G×E |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence variations | Whole genome sequencing, GWAS | Identifies genetic risk variants and their interaction with environmental factors |

| Epigenomics | Heritable changes in gene expression without DNA sequence alteration | ChIP-seq, bisulfite sequencing, ATAC-seq | Captures molecular modifications that respond to environmental exposures |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression dynamics | RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq | Reveals how environmental factors alter gene expression patterns |

| Proteomics | Protein functions and interactions | LC-MS/MS, affinity-based methods | Connects genetic and environmental influences to functional protein-level effects |

| Exposomics | Lifelong environmental exposures | Sensors, geographical data, questionnaires | Quantifies cumulative environmental burden that interacts with genetic makeup |

Core Omics Technologies and Methodologies

Genomics and Epigenomics

Genomics, the most established omics technology, has profoundly enhanced our understanding of NCDs through extensive profiling of genetic variants including SNPs, insertions-deletions, and structural variants [36]. Pioneering advancements in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have been crucial, providing extensive genome-wide coverage that is faster and more cost-effective than ever before [36]. To date, over 6000 genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been conducted for more than 3000 traits, yielding thousands of associated genetic variants [36]. These studies genotype thousands of cases and controls to identify statistically significant genetic associations between particular variants and disease phenotypes [35].

Epigenomics explores the molecular modifications that regulate gene activity without changing the DNA sequence, serving as a crucial interface between the genome and environmental exposures [36]. Techniques such as chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and bisulfite sequencing enable researchers to map epigenetic marks including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility [35]. These epigenetic mechanisms dynamically respond to environmental changes, affecting gene expression and cellular functions, representing key mechanisms through which G×E interactions manifest [36].

Transcriptomics, Proteomics, and Exposomics

Transcriptomics examines gene expression dynamics through technologies such as RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), which quantifies the complete set of RNA transcripts in a biological sample under specific environmental conditions [36]. This layer provides critical insights into how genetic variants and environmental exposures converge to alter gene expression patterns. Advanced methods like single-cell RNA-seq enable researchers to investigate transcriptional responses at cellular resolution, revealing cell-type-specific effects of environmental exposures [36].

Proteomics investigates the complete set of proteins and their functions, providing a direct link to phenotypic manifestations [38]. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enables identification and quantification of thousands of proteins, along with their post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation and acetylation [37]. These PTMs fine-tune protein activities in response to developmental and environmental changes and have profound impacts on phenotypic diversities and trait variations [37].