Evolutionary Constraint in Mammalian Genomics: From Molecular Foundations to Clinical Breakthroughs

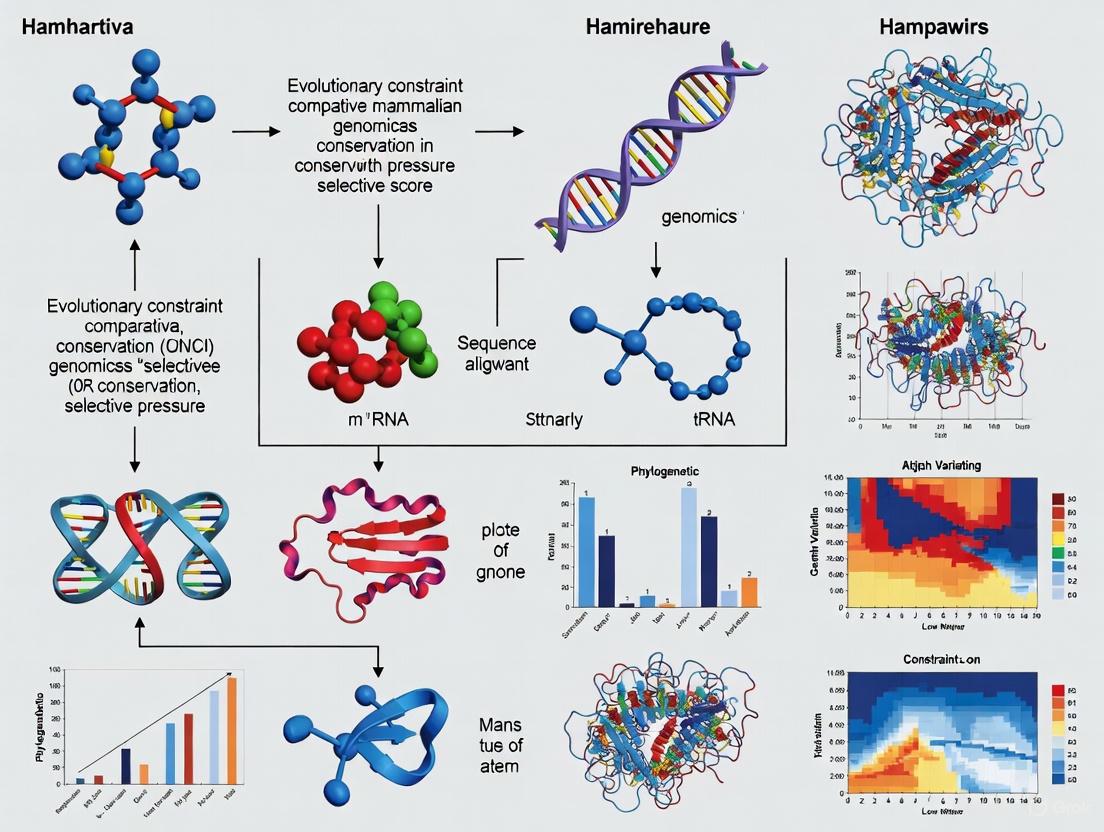

This article explores the critical role of evolutionary constraint in mammalian comparative genomics and its direct impact on biomedical research.

Evolutionary Constraint in Mammalian Genomics: From Molecular Foundations to Clinical Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of evolutionary constraint in mammalian comparative genomics and its direct impact on biomedical research. We first establish the foundational principles of conserved genomic elements and their identification. The discussion then progresses to advanced methodologies for detecting evolutionary signatures, such as accelerated regions and positive selection. A key focus is troubleshooting common challenges, including the high failure rates in drug development linked to a lack of genetic evidence. Finally, the article validates these approaches by demonstrating how evolutionary constraint serves as a powerful filter for prioritizing drug targets and understanding complex traits, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Blueprint of Life: Uncovering Conserved Elements in Mammalian Genomes

Defining Evolutionary Constraint and Genomic Conservation

In the field of comparative mammalian genomics, evolutionary constraint refers to the limited sequence evolution over time due to strong purifying selection acting on functional regions of the genome. It is a signature of biological importance, indicating that a mutation in that region has been selected against because it impairs a critical function, such as protein structure, gene regulation, or RNA processing. Genomic conservation is the observable pattern of sequence similarity across species that results from this constraint, serving as a powerful indicator of functional elements without prior knowledge of their molecular roles [1] [2].

The study of evolutionary constraint is foundational for interpreting genetic variation and understanding the functional architecture of genomes. It operates on the principle that common features between species are often encoded within evolutionarily conserved DNA sequences, allowing researchers to distinguish functionally important elements from neutrally evolving sequences [3] [2].

Quantifying Constraint: Methodologies and Metrics

Phylogenetic Conservation Scores (phyloP)

A primary method for quantifying base-pair-level constraint involves using phylogenetic conservation scores, such as phyloP. These scores are derived from multiple species sequence alignments and quantify the deviation of the observed sequence evolution from a neutral model of evolution [1] [2].

- Calculation: phyloP scores are generated from multi-species sequence alignments, such as the 240-species placental mammal alignment from the Zoonomia Project [1].

- Interpretation:

- Positive scores indicate constrained evolution (slower evolution than expected under neutrality, suggesting purifying selection).

- Scores near zero indicate neutral evolution.

- Negative scores indicate accelerated evolution (faster than expected) [1].

- Significance Threshold: A false discovery rate (FDR) threshold is often applied to identify sites under significant constraint. For the Zoonomia data, sites with a phyloP score ≥2.27 are considered significantly constrained at a 5% FDR [1].

Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling (GERP)

Another widely used method is Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling (GERP), which identifies constrained elements (CEs) by measuring the deficiency of substitutions in multiple alignments compared to the neutral expectation [2]. These elements are then used as a framework to interpret the functional impact of genetic variants present in individual genomes or populations.

Table 1: Proportion of Significantly Conserved Sites in Mammalian Protein-Coding Genes (phyloP ≥ 2.27) [1]

| Site Type | Functional Implication | Proportion Conserved |

|---|---|---|

| Nondegenerate Sites | Affect amino acid sequence | 74.1% |

| Twofold Degenerate (2d) Sites | Some synonymous, some amino acid changes | 36.6% |

| Threefold Degenerate (3d) Sites | Predominantly synonymous | 29.4% |

| Fourfold Degenerate (4d) Sites | Purely synonymous | 20.8% |

Mammalian Synonymous Site Conservation: A Case Study in Constraint

Synonymous sites, particularly four-fold degenerate (4d) sites, were historically considered neutral. However, recent research reveals that a significant fraction is under evolutionary constraint. An analysis of 2.6 million 4d sites across 240 placental mammal genomes found that 20.8% show significant conservation (phyloP ≥ 2.27) [1]. This conservation provides a model for investigating the mechanisms of constraint.

Key Drivers of Synonymous Site Constraint

- Exon Splicing Enhancement: Conservation is high at sites critical for accurate exon splicing, as proper transcript processing is essential for gene function [1].

- Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation: Conserved synonymous sites in developmental genes (e.g., homeobox genes) are often involved in epigenetic regulation, and these genes also exhibit lower mutation rates [1].

- The Unwanted Transcript Hypothesis (UTH): This hypothesis posits that high GC content at synonymous sites in native transcripts helps distinguish them from spurious, non-functional transcripts (e.g., from transposable elements or viral integrations). Spurious transcripts are often AT-rich, intronless, and have high CpG content, marking them for cellular degradation. Conservation of GC-rich sequences at synonymous sites thus protects against the costly production of unwanted transcripts, particularly in species with low effective population sizes like mammals [1].

Table 2: Base Composition at Human Four-Fold Degenerate (4d) Sites [1]

| Site Category | A | T | C | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All 4d Sites | ~25% | ~25% | ~25% | ~25% |

| Conserved 4d Sites (phyloP ≥ 2.27) | ~10% | ~10% | ~40% | ~40% |

Neutral Processes Mimicking Constraint

A critical aspect of interpretation is distinguishing true selective constraint from signatures left by neutral processes.

- GC-Biased Gene Conversion (gBGC): This meiotic process biases allele conversion towards GC base pairs, mimicking the signal of purifying selection for GC content. It is a primary driver of the high GC content observed at synonymous sites in mammals [1].

- Mutation Rate Heterogeneity: Variation in local mutation rates, influenced by factors like gene methylation, can lead to different rates of sequence divergence independently of selection [1].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Constrained Elements

Protocol 1: Identification and Population Genetic Analysis of Constrained Elements

This protocol details how to identify constrained elements and validate their functional significance using human genetic variation [2].

- Identify Constrained Elements: Use a tool like GERP on a multiple sequence alignment (e.g., from the Zoonomia Project) to identify genomic regions with a significant deficiency of substitutions (Rejected Substitutions or RS scores) [2].

- Design PCR Amplicons: Design primers to amplify these Constrained Elements (CEs), including some flanking neutral sequence for comparison.

- Resequencing: Sequence the amplicons across a multi-population cohort of individuals (e.g., 432 individuals from five geographically distinct populations).

- Variant Calling and Filtration: Identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and perform rigorous quality control.

- Allele Frequency Spectrum Analysis: Infer the derived allele by comparison to an outgroup (e.g., chimpanzee) and plot the derived allele frequency (DAF) spectrum.

- Interpretation: A DAF spectrum strongly skewed towards rare alleles in CEs, compared to flanking neutral regions, provides evidence that purifying selection has been acting against variants in the CEs throughout recent human demographic history [2].

Protocol 2: Comparative Genomics Pipeline for Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

This protocol, adapted from a study on Rhodococcus, outlines a high-throughput bioinformatics approach for comparative genomic analysis [4].

- Genome Acquisition and Curation: Download genomes from public databases (e.g., NCBI RefSeq) and include any novel, high-quality internal genomes.

- Data Filtering (Genome Level):

- Filter genomes by assembly quality (e.g., <200 contigs).

- Assess completeness (>98%) and contamination (<5%) using CheckM.

- Perform dereplication by calculating Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and removing highly similar genomes (>98% ANI).

- Functional Element Prediction: Use specialized tools (e.g., antiSMASH for Biosynthetic Gene Clusters - BGCs) to predict functional elements of interest in the filtered genome set.

- Comparative Analysis:

- Phylogenomics: Build a robust phylogenomic tree from core genes.

- Sequence Similarity Networking: Use a tool like BiG-SCAPE to group predicted BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on sequence similarity.

- Integration and Pattern Recognition: Overlay the distribution of GCFs onto the phylogenomic tree to identify patterns of vertical descent or horizontal transfer and prioritize unique BGCs for further study [4].

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Constraint and Conservation Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Zoonomia Project 240-Species Alignment | A massive multiple sequence alignment of placental mammals used to calculate base-pair-level conservation scores (e.g., phyloP) and identify constrained elements [1]. |

| GERP (Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling) | Software that calculates rejected substitution (RS) scores to identify evolutionarily constrained genomic elements from multiple sequence alignments [2]. |

| phyloP | A program that computes p-values for conservation or acceleration at each site in a genome alignment, providing a measure of evolutionary constraint [1]. |

| antiSMASH | A standalone or web-based pipeline for the automated genome-wide identification, annotation, and analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in bacterial and fungal genomes [4]. |

| BiG-SCAPE | A tool for constructing sequence similarity networks of BGCs, allowing their classification into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) to explore their diversity and evolutionary relationships [4]. |

| CheckM | A tool for assessing the quality of microbial genomes derived from isolates, single cells, or metagenomes by estimating completeness and contamination [4]. |

The precise definition and measurement of evolutionary constraint provide a powerful, annotation-agnostic framework for interpreting personal genomes and understanding functional genetics. Key insights reveal that putatively functional variation in an individual is dominated by noncoding polymorphisms that commonly segregate in human populations, underscoring that restricting analysis to coding sequences alone overlooks the majority of functional variants [2].

For drug development professionals, evolutionary constraint serves as a critical filter for prioritizing genetic variants from association studies and for guiding the discovery of functionally important, and often druggable, genomic elements. The integration of comparative genomics with functional studies bridges the gap between sequence conservation and biological mechanism, directly informing target identification and validation strategies.

The completion of the human genome project revealed that only a small fraction of our DNA (approximately 1-2%) codes for proteins, prompting intense scientific interest in the functional significance of the remaining non-coding regions. Evolutionary constraint, which identifies genomic sequences that have changed more slowly than expected under neutral drift due to purifying selection, has emerged as a powerful, agnostic approach for identifying functional elements in these non-coding regions [5]. This technical guide focuses on two sophisticated computational methods—phastCons and PhyloP—that leverage principles of comparative genomics to identify conserved non-coding elements (CNEs) with exceptional precision. These methods are particularly valuable because they can predict functional importance regardless of cell type, developmental stage, or disease mechanism, making them complementary to experimental functional genomics resources like ENCODE and GTEx [5].

Within mammalian genomics, approximately 3.3% of bases in the human genome show significant evolutionary constraint, with the vast majority (80.7%) residing in non-coding regions [5]. These constrained non-coding elements are disproportionately located near developmental genes and often function as crucial regulatory elements, such as enhancers that coordinate spatial-temporal gene expression during embryonic development [6]. The identification and characterization of these elements has become a cornerstone of evolutionary genomics and has profound implications for understanding the genetic basis of both shared mammalian traits and human diseases.

Theoretical Foundations: phastCons and PhyloP

Core Computational Principles

Both phastCons and PhyloP belong to the PHAST (Phylogenetic Analysis with Space/Time models) package and use multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees to identify signatures of selection in genomic sequences. However, they approach the problem from complementary perspectives:

phastCons uses a hidden Markov model (HMM) to identify conserved elements (CEs) based on the probability that each nucleotide belongs to a conserved state. It segments genomes into conserved and non-conserved regions by evaluating patterns of conservation across multiple species simultaneously. The method is particularly effective for identifying relatively long, consistently conserved elements and has been widely used to define sets of conserved non-coding elements (CNEs) across various evolutionary distances [6] [7].

PhyloP employs a phylogenetic p-value approach to test the null hypothesis of neutral evolution at individual nucleotides or predefined elements. Instead of identifying conserved elements directly, it evaluates whether observed patterns of substitution across a phylogeny deviate significantly from neutral expectations, allowing it to detect both significantly conserved and significantly accelerated (fast-evolving) regions [8].

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between phastCons and PhyloP

| Feature | phastCons | PhyloP |

|---|---|---|

| Primary function | Identifies conserved elements | Tests for deviation from neutral evolution |

| Statistical framework | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | Likelihood ratio, score, or goodness-of-fit tests |

| Unit of analysis | Regions/elements | Individual sites or predefined elements |

| Output interpretation | Probability of conservation (0-1) | p-value for neutral evolution hypothesis |

| Detection capability | Conservation only | Both conservation and acceleration |

| Lineage-specific analysis | Limited | Extensive (via subtree tests) |

Scoring Systems and Interpretation

The scoring systems for phastCons and PhyloP reflect their different methodological approaches:

phastCons scores range from 0 to 1, with scores closer to 1 indicating higher conservation. These scores represent the posterior probability that a nucleotide belongs to a conserved element based on the HMM. In practice, a score of ≥0.7-0.9 is often used as a threshold for significant conservation, depending on the specific application and evolutionary distance of the species compared [7].

PhyloP scores represent -log p-values under the null hypothesis of neutral evolution. Positive values indicate conservation (slower evolution than neutral expectation), while negative values indicate acceleration (faster evolution than neutral expectation). The absolute magnitude of the score reflects the statistical significance of the deviation from neutrality [9] [8].

Practical Implementation and Workflows

Analytical Framework for CNE Identification

The following diagram illustrates the core analytical workflow for identifying conserved non-coding elements using phastCons and PhyloP:

Experimental Protocol for Comprehensive CNE Analysis

Input Data Requirements:

- Multiple sequence alignment of orthologous genomic regions from target species

- Phylogenetic tree with reliable branch lengths (preferably in expected substitutions per site)

- Neutral reference model typically estimated from fourfold degenerate (4D) sites

phastCons Execution Protocol:

- Estimate conserved elements using the

phastConscommand with species-specific parameters - Recommended parameters for mammalian alignments:

--expected-length=45 --target-coverage=0.3 --rho=0.31 - Process output to extract elements exceeding conservation probability threshold (typically ≥0.7)

PhyloP Execution Protocol:

- Conduct all-branch or subtree tests using

phyloPwith appropriate method flag - Recommended statistical test:

--method LRT(likelihood ratio test) for balanced sensitivity/specificity - Adjust for multiple testing using false discovery rate (FDR) control, with significance threshold of p < 0.05

Validation and Filtering:

- Annotate elements with genomic coordinates relative to known genes

- Filter out coding sequences using genome annotation files

- Prioritize elements based on conservation scores and genomic context

Applications in Mammalian Genomics Research

Key Biological Insights from Large-Scale Projects

The application of phastCons and PhyloP in large-scale genomic consortia has yielded fundamental insights into mammalian genome evolution and function:

The Zoonomia Project, which analyzed 240 placental mammalian species, demonstrated that evolutionary constraint effectively identifies functional elements, with 3.3% of the human genome showing significant constraint. This constraint information has proven more enriched for disease single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-heritability (7.8-fold enrichment) than other functional annotations, including nonsynonymous coding variants (7.2-fold) and fine-mapped expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL)-SNPs (4.8-fold) [5].

Mammalian and Avian Accelerated Regions identified through PhyloP analysis have revealed hotspots of evolutionary innovation. A 2025 study identified 3,476 noncoding mammalian accelerated regions (ncMARs) and 2,888 avian accelerated regions (ncAvARs) clustered in key developmental genes. Remarkably, the neuronal transcription factor NPAS3 contained the largest number of human accelerated regions (HARs) and also accumulated numerous ncMARs, suggesting certain genomic loci are repeatedly targeted during lineage-specific evolution [10].

Interpretation Framework for Conservation Scores

The diagram below illustrates the decision process for interpreting phastCons and PhyloP scores in biological contexts:

Quantitative Findings from Recent Studies

Table 2: Distribution of Constrained and Accelerated Elements in Vertebrate Genomes

| Genomic Category | Mammals | Birds | Functional Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constrained bases | 3.3% of human genome [5] | N/A | Disease heritability (7.8×) [5] |

| Coding constrained bases | 57.6% of coding sequence [5] | N/A | Pathogenic variants [5] |

| Noncoding accelerated elements | 3,476 ncMARs [10] | 2,888 ncAvARs [10] | Developmental genes [10] |

| Coding accelerated elements | 20,531 cMARs [10] | 2,771 cAvARs [10] | Various functions [10] |

| Proportion noncoding | 14.4% of MARs [10] | 51% of AvARs [10] | Lineage-specific differences [10] |

Table 3: Essential Resources for CNE Identification and Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHAST package | Software | phastCons & PhyloP implementation | All-branch and subtree tests; multiple statistical methods [8] |

| Zoonomia Constraint | Database | Mammalian constraint scores | 240-species phyloP scores; 3.3% constrained bases identified [5] |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Platform | Conservation visualization | phastCons and phyloP tracks for 30-44 vertebrate species [7] [8] |

| UCNEbase | Database | Ultraconserved non-coding elements | ≥95% identity over 200bp in human-chicken genomes [6] |

| ANCORA | Database | Conserved regions in animals | ≥70% sequence identity over 30-50bp in metazoa [6] |

| VISTA Enhancer Browser | Database | Experimentally validated enhancers | In vivo tested enhancer activity with conservation data [6] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integration with Functional Genomics

The true power of phastCons and PhyloP emerges when integrated with functional genomic data. A 2025 study demonstrated that while most cis-regulatory elements (CREs) in embryonic mouse and chicken hearts lack sequence conservation (only ~10% of enhancers show conservation), synteny-based algorithms can identify up to fivefold more orthologous CREs than alignment-based approaches alone [11]. This suggests that functional conservation often persists despite sequence divergence, highlighting the importance of combining evolutionary constraint analyses with chromatin profiling and spatial genomic organization data.

Advanced approaches now combine phastCons/PhyloP with:

- Chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) to validate regulatory potential

- Three-dimensional chromatin architecture (Hi-C) to connect elements with target genes

- Machine learning models to predict enhancer activity across species

- Massively parallel reporter assays for high-throughput functional validation

Translational Applications in Disease Genomics

Evolutionary constraint metrics have profound implications for human disease research. Pathogenic variants in ClinVar are significantly more constrained than benign variants (P < 2.2 × 10⁻¹⁶) [5], enabling improved variant prioritization. Furthermore, incorporating constraint information enhances functionally informed fine-mapping and improves polygenic risk score accuracy across multiple traits [5].

The application of these methods extends to cancer genomics, where constraint information helps distinguish driver from passenger mutations in non-coding regions. For example, incorporating constraint into the analysis of non-coding somatic variants in medulloblastomas has identified novel candidate driver genes that would have been missed by conventional approaches [5].

phastCons and PhyloP represent sophisticated computational approaches that leverage deep evolutionary history to identify functional non-coding elements in mammalian genomes. While phastCons excels at identifying broadly conserved elements through its HMM framework, PhyloP provides greater flexibility for detecting both conservation and acceleration in specific lineages. Together, these methods have revealed that approximately 3.3% of the human genome shows evidence of functional constraint, with the vast majority residing in non-coding regions that likely regulate crucial biological processes, particularly during development.

As genomic datasets continue to expand in both size and taxonomic breadth, the precision and utility of these evolutionary analyses will only increase. Future directions will likely focus on integrating these comparative genomic approaches with single-cell functional genomics, sophisticated machine learning models, and high-throughput experimental validation to comprehensively decipher the regulatory code of mammalian genomes. For drug development professionals and biomedical researchers, understanding and applying these tools is becoming increasingly essential for translating genomic discoveries into biological insights and therapeutic innovations.

The study of evolutionary constraint provides a powerful lens for identifying functional genomic elements. Regions that are highly conserved across vast evolutionary timescales are presumed to be under purifying selection due to their biological importance. A compelling phenomenon occurs when these normally constrained sequences exhibit unexpectedly accelerated substitution rates along specific lineages. These genomic elements, known as accelerated regions, serve as natural experiments that reveal genomic locations potentially underlying clade-defining traits [10].

Mammalian and Avian Accelerated Regions (MARs and AvARs) represent sequences highly conserved across vertebrates that subsequently accumulated substitutions at faster-than-neutral rates in the basal mammalian or avian lineages, respectively [10]. Their identification relies on comparative genomic approaches that detect the signature of relaxed constraint or positive selection acting on previously conserved elements. This case study examines the identification, functional validation, and evolutionary significance of MARs and AvARs within the broader context of comparative mammalian genomics research, highlighting how the breakdown of evolutionary constraint in specific lineages can illuminate the genetic basis of phenotypic innovation.

Identification and Genomic Characteristics of MARs and AvARs

Computational Identification Pipeline

The discovery of accelerated regions requires a multi-step phylogenetic approach that integrates both conservation and acceleration signals across vertebrate genomes. The standard methodology involves:

Genome Alignment and Conservation Detection: The process begins with whole vertebrate genome alignments. Using the phastCons program from the PHAST package, researchers identify sequences that have remained highly conserved across vertebrate evolution [10]. For mammalian studies, a requirement is that the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), as a basal mammalian species, must be present in alignments and share nucleotide changes with other mammals [10].

Acceleration Detection with phyloP: The conserved sequences are then analyzed using the phyloP software to detect lineage-specific acceleration signals [10]. This program employs likelihood ratio tests to identify regions where the substitution rate in a target lineage (e.g., basal mammals or birds) significantly exceeds the neutral expectation [10] [12].

Lineage-Specific Filtering: For AvAR identification, the methodology requires that at least one early-diverging bird (white-throated tinamou or ostrich) shares nucleotide changes with other bird species while differing from the consensus sequence of other tetrapods [10]. This ensures the identified regions represent true avian-specific accelerations.

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for Identifying Accelerated Regions

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| phastCons | Identifies evolutionarily conserved regions across multiple species | Conservation threshold, minimum element size (typically 100bp) |

| phyloP | Detects lineage-specific acceleration in conserved regions | Likelihood ratio tests, branch-specific models |

| Evolutionary Rate Decomposition | Discovers genes with covarying evolutionary rates across lineages | Principal component analysis of rate variation [13] |

Genomic Distribution and Properties

Recent research has revealed striking differences in the genomic distribution and characteristics of MARs versus AvARs:

Quantity and Coding vs. Non-coding Distribution: Researchers identified 24,007 mammalian accelerated regions (MARs), of which 85.6% (20,531) were coding (cMARs) and only 14.4% (3,476) were noncoding (ncMARs) [10]. In contrast, birds exhibited 5,659 Avian Accelerated Regions (AvARs) with a nearly equal distribution between coding (49%, 2,771) and noncoding (51%, 2,888) elements [10].

Lineage-Specific Hotspots: Both MARs and AvARs accumulate in key developmental genes, particularly those encoding transcription factors [10]. A remarkable example is the neuronal transcription factor NPAS3, which carries 30 ncMARs in its locus—the largest number of noncoding mammalian accelerated regions found in any single gene [10]. This gene also carries the largest number of human accelerated regions (HARs), suggesting that certain genomic loci may be repeated targets of accelerated evolution across different lineages [10].

Table 2: Comparative Genomics of Mammalian and Avian Accelerated Regions

| Characteristic | Mammalian Accelerated Regions (MARs) | Avian Accelerated Regions (AvARs) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Identified | 24,007 | 5,659 |

| Noncoding (ncMARs/ncAvARs) | 3,476 (14.4%) | 2,888 (51%) |

| Coding (cMARs/cAvARs) | 20,531 (85.6%) | 2,771 (49%) |

| Key Genomic Hotspots | NPAS3 locus (30 ncMARs) | ASHCE near Sim1 gene [10] |

| Evolutionary Period | Basal mammalian lineage | Basal avian lineage |

Functional Significance and Validation of Accelerated Regions

Functional Enrichment and Phenotypic Associations

Gene ontology analyses reveal that genes associated with both MARs and AvARs are significantly enriched for functions related to development and regulation [10] [12]. Specifically:

Developmental Processes: A substantial proportion (52%) of noncoding HARs are located within 1 megabase of developmental genes [12]. This pattern extends to MARs and AvARs, which are enriched near genes involved in morphological patterning and organogenesis [10].

Neuronal and Cognitive Functions: The NPAS3 locus represents a notable hotspot for accelerated regions across multiple lineages. NPAS3 is a neuronal transcription factor implicated in neurodevelopment, and its associated HARs have been shown to function as enhancers during brain development [10] [12]. This suggests accelerated evolution of regulatory elements influencing brain development and function in multiple lineages.

Shared Phenotypic Traits: Birds and mammals independently evolved several similar traits, including homeothermy, insulation (feathers or hair), similar cardiovascular systems, complex parental care, improved hearing, vocal communication, and high basal metabolism [10]. The convergence of these phenotypes may be reflected in parallel acceleration of regulatory elements governing these traits.

Experimental Validation of Regulatory Function

Traditional Enhancer Assays

Traditional low-throughput methods for validating accelerated regions include transgenic animal models:

Transgenic Mouse Assays: Both human and chimpanzee versions of candidate HARs can be tested in transgenic mice to compare enhancer activity [12]. For example, testing of 29 ncHARs in transgenic mice revealed that 24 functioned as developmental enhancers, with five showing suggestive differences between human and chimpanzee sequences at embryonic day 11.5 [12].

Zebrafish Transgenic Assays: The functional importance of mammalian accelerated regions has been further demonstrated by testing the five most accelerated ncMARs in transgenic zebrafish, all of which exhibited transcriptional enhancer activity [10].

High-Throughput Functional Screening

Recent advances have enabled massively parallel approaches for characterizing non-coding regulatory elements:

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs): These assays enable high-throughput functional screening of thousands of non-coding variants in parallel for their effects on gene expression [14]. Library of putative cis-regulatory sequences are cloned upstream of a minimal promoter driving a reporter gene, transfected into relevant cell types, and regulatory activity is quantified by comparing RNA transcripts to DNA molecules [14].

CRISPR-Based Screening: CRISPR technologies enable direct perturbation of candidate accelerated regions to assess effects on gene expression and phenotypes [14]. Pooled CRISPR screens in human neural stem cells have identified thousands of enhancers impacting proliferation, including many HARs, supporting their importance in human neurodevelopment [14].

Experimental Workflow for Accelerated Regions Research

Evolutionary Dynamics and Drivers of Genomic Acceleration

Life History Correlates of Evolutionary Rates

Genome-wide evolutionary rates in birds show distinctive patterns related to life history traits:

Clutch Size and Generation Length: Analysis of 23 life-history, morphological, ecological, geographical, and environmental traits across birds revealed that clutch size shows a significant positive association with mean dN, dS, and rates in intergenic regions [13]. Generation length emerged as the most important variable in driving molecular rate variation, showing a negative relationship with evolutionary rates [13].

Ecological Correlates: Species-level analyses revealed that taxa with shorter tarsi (often associated with aerial and arboreal lifestyles) exhibited elevated rates of dN and intergenic region evolution [13]. This suggests that flight-intensive lifestyles may be associated with genomically widespread adaptations, potentially related to the oxidative stress of intensive flight [13].

Temporal Dynamics of Genomic Diversity

Temporal genomics approaches comparing historical and modern samples provide insights into recent evolutionary dynamics:

Genomic Diversity Trends: Studies of eight generalist highland bird species from the Ethiopian Highlands revealed an assemblage-wide increase in genomic diversity through time, contrasting with general trends of diversity declines in specialist or imperiled species [15]. This suggests that generalist species may respond differently to anthropogenic environmental changes compared to specialists.

Mutation Load Dynamics: The same study found an assemblage-wide trend of decreased realized mutational load over the past century, indicating that potentially deleterious variation may be selectively purged or masked in these generalist populations [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Accelerated Regions Research

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| phastCons/phyloP | Identifies conserved and accelerated regions from multiple sequence alignments | Requires whole genome alignments; sensitive to alignment quality and species sampling [10] |

| MPRA Libraries | High-throughput testing of thousands of candidate regulatory sequences and variants | Can test synthetic oligos outside endogenous context; requires careful library design [14] |

| CRISPR gRNA Libraries | Pooled screening of regulatory element function in endogenous genomic context | Enables functional screening in relevant cell types; can target non-coding regions systematically [14] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Characterization of cell-type specific gene expression patterns across species | Enables identification of cell-type specific expression differences; requires careful cross-species integration [16] |

| Evolutionary Rate Decomposition | Identifies subsets of genes and lineages that dominate evolutionary rate variation | Uses principal component analysis of rate variation; reveals coordinated evolution [13] |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Genomic studies have revealed specific molecular pathways influenced by accelerated evolution:

Neuronal Function and Connectivity: Comparative single-cell analyses of amniote brains have identified approximately 3,000 differentially expressed homologous genes between birds and mammals, including the paralogous gene pair SLC17A6 and SLC17A7 in cortical excitatory neurons [16]. These genes exhibit significant expression differences associated with genomic variations between species, with structural analyses revealing that minor mutations could induce substantial changes in their transmembrane domains [16].

Cerebellar Specialization: Avian brains contain a distinct Purkinje cell type (SVIL+) marked by significant differentiation and unique gene expression profiles compared to ALDOC+ and PLCB4+ Purkinje cells in mammals [16]. This cell type displays pronounced differences in gene expression, suggesting a distinct evolutionary trajectory that likely reflects unique evolutionary pressures in birds, potentially related to flight adaptation [16].

Regulatory Logic of Accelerated Regions

Mammalian and Avian Accelerated Regions represent powerful natural experiments that reveal how the breakdown of evolutionary constraint in specific lineages can facilitate phenotypic innovation. The integrated approaches discussed—combining comparative genomics, functional validation, and evolutionary analysis—provide a roadmap for understanding how changes in gene regulation contribute to clade-defining traits. Future research in this field will benefit from increased taxonomic sampling, improved functional genomics resources across diverse species, and the application of novel high-throughput methods to dissect the functional consequences of accelerated evolution. These advances will further illuminate the genetic basis of evolutionary innovation and the relationship between genomic constraint and phenotypic diversity.

Evolutionary Hotspots: The NPAS3 Gene Locus as a Paradigm

The NPAS3 (Neuronal PAS domain protein 3) gene encodes a brain-developmental transcription factor of the bHLH–PAS family and presents an exceptional case study in evolutionary genomics. Comparative genomic analyses have consistently identified this locus as containing the largest cluster of human-accelerated regions (HARs) in the human genome, as well as a significant accumulation of mammalian-accelerated regions (MARs) [17] [10] [18]. This whitepaper details how the NPAS3 locus serves as a paradigm for evolutionary hotspots, exploring the functional consequences of its accelerated evolution, its role in neurodevelopment and disease, and the experimental methodologies used to decipher its regulatory landscape. This analysis is framed within the broader context of evolutionary constraint in mammalian genomics, illustrating how certain genomic regions are repeatedly targeted for evolutionary innovation.

Evolutionary constraint, which identifies genomic sequences under purifying selection, provides a powerful lens for pinpointing functional elements in the genome. Comparative analysis of 29 mammalian genomes confirmed that approximately 5.5% of the human genome is under purifying selection, with constrained elements covering about 4.2% of the genome [19]. Within this constrained background, certain loci exhibit signatures of accelerated evolution—lineage-specific rapid accumulation of nucleotide substitutions—suggesting positive selection for functional shifts.

These accelerated regions are often non-coding and can modify gene regulatory networks, thereby contributing to lineage-specific traits. The NPAS3 gene stands out as a premier example. A meta-analysis combining four independent genome-wide scans for human-accelerated elements (HAEs) identified the NPAS3 locus as the most densely populated with non-coding accelerated regions in the entire human genome, containing up to 14 HAEs [18]. More recent comparative genomics work has further revealed that NPAS3 also carries the largest number of non-coding Mammalian Accelerated Regions (ncMARs), with 30 such elements identified in its locus [10]. This repeated targeting by accelerated evolution in both the mammalian and human lineages establishes NPAS3 as a canonical evolutionary hotspot, offering profound insights into the genetic underpinnings of neural evolution and its link to disease.

The NPAS3 Gene: Molecular Function and Clinical Significance

Molecular Structure and Function

NPAS3 is a class I basic helix-loop-helix PER-ARNT-SIM (bHLH-PAS) transcription factor. Its protein structure consists of several key functional domains:

- A bHLH domain for DNA binding and protein interaction.

- Two PAS domains (PAS A and PAS B) involved in protein dimerization and potential ligand binding.

- A C-terminal transactivation domain [20].

NPAS3 functions as a true transcription factor by forming a heterodimer with an obligatory class II bHLH-PAS partner, predominantly ARNT (Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator) or its neuronally enriched isoform ARNT2 [20] [21]. This heterodimer is capable of gene regulation through direct association with E-box DNA sequences in target gene promoters. Key experimentally validated transcriptional targets of NPAS3 include VGF and TXNIP, which have roles in neurogenesis and metabolic regulation [20].

Role in Neurodevelopment and Disease

NPAS3 is predominantly expressed in the developing and adult central nervous system, with critical roles in:

- Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Mouse knockout models show a marked reduction in adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, primarily due to increased apoptosis of neural progenitors [20].

- Cortical Interneuron Formation: Deletion of Npas3 leads to reduced numbers of cortical interneurons born in the subpallial ganglionic eminences [20].

- Behavior and Cognition: Npas3-deficient mice exhibit behavioral deficits, including impaired performance on hippocampal-dependent memory tasks and altered emotional tone [20].

Given its crucial neurodevelopmental functions, it is unsurprising that NPAS3 disruption is linked to psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders. Genetic evidence includes:

- Chromosomal translocations disrupting NPAS3 that segregate with schizophrenia and intellectual disability [20] [22].

- Rare loss-of-function variants (e.g., truncating mutations disrupting the PAS A domain) identified in individuals with developmental delay or intellectual disability [21].

- Associations from genome-wide studies with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and treatment response to antipsychotics [20] [22].

Table 1: Key Domains and Variants of the NPAS3 Protein

| Protein Domain | Function | Consequence of Disruption | Associated Human Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| bHLH | DNA binding; dimerization with ARNT/ARNT2 | Loss of DNA binding and transcriptional activity [20] | --- |

| PAS A | Protein dimerization | Loss of heterodimerization and transcriptional activity; linked to neurodevelopmental disorders [21] | G201R, G229R [21] |

| PAS B | Protein dimerization; ligand binding? | Loss of heterodimerization and transcriptional activity [21] | --- |

| C-terminal | Transactivation | Reduced or altered target gene regulation [20] | --- |

The NPAS3 Locus as an Evolutionary Hotspot

Evidence from Comparative Genomics

The NPAS3 locus is distinguished by an extraordinary high density of lineage-specific accelerated sequences, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Accelerated Evolutionary Elements in the NPAS3 Locus

| Lineage | Type of Accelerated Element | Number Identified | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Human-Accelerated Elements (HAEs/HARs) | 14 (the largest cluster in the human genome) | [17] [18] |

| Mammalian (Basal Branch) | Non-Coding Mammalian Accelerated Regions (ncMARs) | 30 (the largest number for any gene) | [10] |

| Avian | Non-Coding Avian Accelerated Regions (ncAvARs) | A significant accumulation reported | [10] |

This pattern suggests that the NPAS3 regulatory landscape has been a repeated target for evolutionary remodeling across different vertebrate lineages, potentially driving innovations in brain development and function [10].

Functional Validation of Accelerated Elements

Bioinformatic identification of these elements is supported by robust functional assays. A seminal study tested the enhancer activity of 14 NPAS3 HAEs in transgenic zebrafish and found that 11 (79%) functioned as transcriptional enhancers during development, with most driving expression in the nervous system [18]. This confirms that these accelerated sequences are bona fide regulatory elements.

One of the best-characterized examples is the 2xHAR142 element, located in the fifth intron of NPAS3. Transgenic mouse assays revealed that the human version of 2xHAR142 drives an extended expression pattern of a reporter gene (lacZ) in the developing forebrain, including the cortex, compared to the orthologous sequences from chimpanzee and mouse [17]. This provides direct experimental evidence that human-specific nucleotide substitutions in this hotspot element altered its function as a developmental enhancer, potentially contributing to the evolution of human-specific brain features—a phenomenon known as human-specific heterotopy [17].

Experimental Methodologies for Analyzing Hotspot Function

Characterizing Transcription Factor Function

To molecularly characterize NPAS3 and its variants, a suite of standard molecular biology techniques are employed, as detailed in mechanistic studies [20] [21].

Key Protocol: Assessing NPAS3 Transcriptional Activity via Reporter Gene Assay

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the coding sequence of NPAS3 (and its variants) into an expression vector (e.g., pcI-HA). A reporter plasmid contains a firefly luciferase gene under the control of a minimal promoter and upstream E-box elements. A control Renilla luciferase plasmid is used for normalization.

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Culture HEK 293T cells in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with high glucose at 37°C and 5% CO₂. Plate cells and transfect 24 hours later using a transfection reagent (e.g., Mirus TransIT-LT1) with a mix of the NPAS3 expression plasmid, the reporter plasmid, and the control plasmid.

- Reporter Gene Assay: Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-transfection. Measure firefly and Renilla luciferase activities using a dual-luciferase assay system. Normalize firefly luciferase activity to Renilla activity to calculate relative transcriptional activity [20] [21].

Key Protocol: Verifying Protein-Protein Interaction via Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

- Cell Lysis: Lyse transfected cells (e.g., HEK 293T) expressing NPAS3 and ARNT (or ARNT2) in a non-denaturing lysis buffer.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the cell lysate with an antibody specific to a tag on one protein (e.g., HA-tag on NPAS3) and protein A/G beads. Use a control IgG for a negative control.

- Western Blot: Wash the beads extensively to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound proteins and separate them by SDS-PAGE. Transfer to a membrane and probe with antibodies against the interaction partner (e.g., ARNT) to detect co-precipitation [21].

Validating Enhancer Activity In Vivo

To test the function of non-coding accelerated elements identified in the NPAS3 locus, transgenic animal models are the gold standard.

Key Protocol: Testing Enhancer Activity with Transgenic Mice

- Element Cloning: Clone the conserved non-coding accelerated element (e.g., 2xHAR142 from human, chimp, and mouse) upstream of a minimal promoter (e.g., Hsp68) driving the lacZ reporter gene.

- Generation of Transgenic Mice: Microinject the constructed vector into fertilized mouse oocytes to generate multiple independent founder transgenic lines for each species' ortholog of the element.

- Expression Analysis: At specific developmental stages (e.g., E10.5, E12.5, E14.5), harvest embryos and stain for β-galactosidase activity to visualize the spatial pattern of lacZ expression driven by the enhancer. Compare patterns driven by orthologs from different species to identify lineage-specific changes [17].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key findings from this experimental approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogues essential materials and reagents used in the featured NPAS3 experiments, providing a resource for researchers seeking to replicate or extend these findings.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NPAS3 and Evolutionary Hotspot Studies

| Reagent / Material | Specific Example / Assay | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Gateway-converted pcI-HA vector [20] | For cloning and expressing tagged NPAS3 and its domain constructs in mammalian cells. |

| Tagged Protein Systems | HaloTag-ARNT, HA-tagged NPAS3 [20] | Facilitates protein detection, purification, and interaction studies (e.g., Co-IP). |

| Reporter Gene Systems | Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System [21] | Quantifies transcriptional activity of NPAS3:ARNT heterodimers on target promoters. |

| Cell Lines | HEK 293T cells [20] | A robust model system for transient transfection and functional characterization of transcription factors. |

| Transgenic Constructs | Hsp68-minimal-promoter-lacZ vector [17] | The standard construct for testing enhancer activity of genomic elements in vivo. |

| Antibodies for Immunodetection | Anti-HA antibody, Anti-ARNT antibody [20] [21] | Critical for Western Blot and Co-Immunoprecipitation experiments to confirm protein expression and interactions. |

The NPAS3 gene locus stands as a powerful paradigm for understanding evolutionary hotspots. Its unique status, arising from the convergence of extreme genomic features—the largest clusters of both human and mammalian accelerated regions—highlights the existence of specific genomic "hotspots" that are repeatedly targeted for evolutionary innovation across lineages [10] [18]. The functional characterization of these elements has demonstrated that accelerated evolution has likely modified the NPAS3 regulatory landscape, contributing to the complex spatiotemporal control of a critical neurodevelopmental transcription factor [17].

Future research must focus on elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms by which these accelerated regions fine-tune NPAS3 expression and how these changes have impacted human brain circuitry and cognitive specializations. Furthermore, understanding how genetic variation within these hotspots predisposes to psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders represents a critical frontier for translational neuroscience. The NPAS3 locus exemplifies how integrating comparative genomics with rigorous experimental validation can unravel the genetic architecture underlying both evolutionary adaptations and human disease.

In the field of comparative mammalian genomics, evolutionary constraint—the phenomenon where DNA sequences are preserved through purifying selection—serves as a powerful indicator of functional importance. Research has demonstrated that approximately 5.5% of the human genome has undergone purifying selection, with constrained elements covering roughly 4.2% of the genome [23]. These conserved regions represent crucial functional components that have been maintained throughout mammalian evolution, while carefully identified accelerated regions reveal where rapid evolution may have driven phenotypic innovations. This technical guide examines the methodologies and analytical frameworks that enable researchers to decipher the functional significance of genomic sequences, with a particular focus on the interplay between constraint and innovation in shaping mammalian phenotypes.

Decoding Evolutionary Signatures in Genomic Sequences

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

- Evolutionary Constraint: The action of purifying selection that preserves functional genomic sequences against mutation across evolutionary time, indicating biological importance [23].

- Accelerated Regions: Genomic sequences, either coding or non-coding, that have accumulated substitutions at a faster-than-neutral rate in specific lineages, often associated with phenotypic adaptations [10].

- Phenotypic Plasticity: The ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions, representing an alternative evolutionary strategy to genetic canalization [24].

Quantitative Landscape of Constrained and Accelerated Elements in Mammals

Table 1: Genomic Elements Under Evolutionary Selection in Mammals

| Element Type | Genomic Proportion | Number of Elements | Primary Genomic Location | Functional Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Constrained Sequence | 5.5% of human genome | 3.6 million elements | 4.2% of genome | Various functional elements |

| Mammalian Accelerated Regions (MARs) | Not quantified | 24,007 total (3,476 noncoding) | 85.6% coding, 14.4% noncoding | Key developmental genes |

| Avian Accelerated Regions (AvARs) | Not quantified | 5,659 total (2,888 noncoding) | 49% coding, 51% noncoding | Developmental transcription factors |

| Human Accelerated Regions (HARs) | >1,000 elements | ~3,000 elements | Predominantly non-coding | Brain development, neurological diseases |

Experimental Methodologies for Detecting Evolutionary Signatures

Identification of Conserved and Accelerated Elements

The standard pipeline for identifying evolutionary significant regions involves multiple computational steps utilizing specialized software tools.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Evolutionary Genomics

| Method Objective | Tools Used | Key Parameters | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identify conserved sequences | phastCons (PHAST package) [10] | Minimum 100bp size; vertebrate conservation | 93,881 conserved mammalian sequences; 155,630 conserved avian sequences |

| Detect acceleration signals | phyloP (PHAST package) [10] | Lineage-specific substitution rates vs. neutral expectation | 24,007 MARs; 5,659 AvARs |

| Multiple sequence alignment | Multiz [23], LAST, MACSE, PRANK [25] | Phylogenetic tree-aware alignment | Codon-level alignment for orthologous genes |

| Detect positive selection in coding sequences | PAML codeml (branch-site model) [25] | ModelA: model=2, NSsites=2, fix_omega=0, omega=1.5 | Likelihood Ratio Test with BH correction, p<0.01 |

Workflow for Comparative Genomic Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for identifying and validating functionally significant genomic elements:

From Sequence to Function: Mechanistic Insights

Structural Clustering of Positively Selected Sites

Advanced analyses integrating evolutionary sequence data with protein structural information reveal that positively selected sites frequently cluster in three-dimensional space rather than distributing randomly. These clusters predominantly localize to functionally important regions of proteins, contravening the conventional principle that functionally important regions are exclusively conserved [26]. This pattern is particularly evident in:

- Immune-related proteins (e.g., MHC molecules, toll-like receptors)

- Metabolic enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450 family members)

- Detoxification systems

The clustering of positively selected sites in structurally and functionally coordinated regions suggests that adaptive evolution often acts through concerted changes at multiple residues that jointly alter protein function, rather than through isolated changes with small individual effects [26].

Phenotypic Plasticity as an Evolutionary Strategy

Experimental evolution studies demonstrate that environmental variability can select for increased phenotypic plasticity rather than genetic canalization. Research in nematode worms revealed that exposure to fast temperature cycles with little parent-offspring environmental autocorrelation led to the evolution of increased body size plasticity compared to slowly changing environments with high autocorrelation [24]. This plasticity followed the temperature-size rule (decreased size at higher temperatures) and was adaptive, illustrating how environmental patterns shape genomic strategies for phenotype generation.

In agricultural systems, studies of wheat improvement have documented systematic changes in phenotypic plasticity for 17 agronomic traits during domestication from landraces to cultivars. The reaction norm parameters (intercept and slope) based on environmental indices captured trait variation across environments, revealing that plant architecture traits and yield components exhibited distinct patterns of plasticity evolution [27].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Evolutionary Genomics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Alignment Tools | Multiz, LAST, PRANK, MACSE | Multiple sequence alignment and codon-level analysis |

| Evolutionary Rate Analysis | PAML codeml, SiPhy-ω, SiPhy-π | Detection of selection pressure and substitution patterns |

| Conservation/Acceleration Detection | phastCons, phyloP (PHAST package) | Identification of constrained and accelerated elements |

| Genomic Datasets | Zoonomia Project (240 species), B10K Project (363 bird genomes) | Comparative genomic frameworks across mammals and birds |

| Functional Validation | Transgenic zebrafish assays, CRISPR screens | Experimental testing of regulatory element function |

| Multi-omics Integration | GWAS, environmental indices (CERIS) | Linking genomic variation to phenotypic outcomes |

Case Studies: Integrated Analysis of Evolutionary Innovation

NPAS3: A Hotspot of Mammalian Regulatory Evolution

The neuronal transcription factor NPAS3 exemplifies how specific genomic loci can serve as repeated targets for evolutionary innovation. Research has revealed that NPAS3 carries:

- The largest number of human accelerated regions (HARs) of any gene

- 30 noncoding mammalian accelerated regions (ncMARs) in its locus

- Multiple noncoding avian accelerated regions (ncAvARs)

This concentration of accelerated elements in a transcription factor involved in neuronal development suggests that regulatory rewiring of developmental genes represents a fundamental mechanism for phenotypic evolution across multiple lineages [10]. The recurrence of acceleration in the same gene across different evolutionary lineages indicates the existence of evolutionary hotspots that are particularly amenable to functional innovation.

Long-Distance Migration in Mammals: Convergent Molecular Evolution

Comparative genomic analysis of 21 long-distance migratory mammals has identified distinct evolutionary signatures associated with this complex behavior. Researchers detected:

- Positive selection in genes related to memory, sensory perception, and locomotor abilities

- Accelerated evolution in coding sequences underlying energy metabolism and stress response

- Convergent evolution in biological processes including genomic stability and navigation

These molecular adaptations illustrate how similar phenotypic innovations (migration) can arise through parallel genetic mechanisms in distantly related species, highlighting the predictive power of comparative genomic approaches for understanding complex traits [25].

Future Directions and Implementation Considerations

The integration of evolutionary genomics with functional validation represents the frontier of understanding how genomic sequences translate to phenotypic innovation. Key emerging approaches include:

- Single-cell genomics and spatial transcriptomics for resolving cellular heterogeneity in phenotypic responses [28]

- Multi-omics integration combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data [28]

- Machine learning applications for predicting functional consequences of evolutionary signatures [28]

- Advanced genome editing using CRISPR-based screens to validate putative functional elements [28]

Implementation of these approaches requires careful consideration of statistical power, multiple testing corrections, and functional validation strategies to distinguish causal relationships from correlative associations. The continued expansion of genomic resources across diverse species will further enhance our ability to decipher the functional significance of genomic sequences and their role in phenotypic innovation.

Decoding the Signals: Methods for Detecting Evolutionary Signatures and Their Applications

In the field of comparative mammalian genomics, understanding evolutionary constraint is pivotal for identifying functionally important genomic regions and linking genetic variation to phenotypic outcomes and disease. This whitepaper details a core bioinformatics toolkit—comprising the PHAST software suite, the PAML package, and Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) models—that enables researchers to detect signatures of natural selection and evolutionary constraint. We provide a technical guide on the application of these tools, complete with experimental protocols, data interpretation guidelines, and visualization workflows. Framed within contemporary studies of mammalian evolution, including analyses of longevity, migration, and base-level constraint, this resource equips scientists and drug development professionals with methodologies to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying complex traits and disease.

Evolutionary constraint, measured by the signature of purifying selection acting on genomic elements, serves as a powerful and mechanism-agnostic predictor of biological function. Recent analyses of whole-genome alignments from 240 placental mammals have identified that 3.5% of the human genome is significantly constrained, enriching for variants explaining common disease heritability more than any other functional annotation [29]. Such constrained regions are critical for interpreting genome-wide association studies (GWAS), copy number variations, and clinical genetics findings.

The quantitative analysis of evolutionary constraint relies on a sophisticated statistical toolkit that accounts for phylogenetic relationships among species. This guide focuses on three essential components: PHAST (PHASTcons, PHyloP), for base-wise conservation scores from multiple sequence alignments; PAML (Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood), particularly its CODEML program for detecting selection in protein-coding genes; and Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS), for testing trait correlations while controlling for shared evolutionary history [29] [30] [31]. Together, these tools enable researchers to move from genomic alignments to biological insights about mammalian adaptation, longevity, and disease.

The PHAST Software Suite

The PHAST (Phylogenetic Analysis with Space/Time Models) software suite enables genome-scale phylogenetic modeling, with its most widely used tools being phyloP and phastCons. These programs calculate evolutionary conservation and constraint by comparing observed patterns of nucleotide substitution across a multiple sequence alignment to expectations under a neutral model of evolution.

Core Functions and Applications

- phyloP: Uses phylogenetic p-values to measure conservation or acceleration at individual alignment columns. Negative scores indicate faster-than-neutral evolution (acceleration), while positive scores indicate slower-than-neutral evolution (constraint) [29].

- phastCons: Uses a phylogenetic hidden Markov model (phylo-HMM) to identify conserved elements by segmenting the genome into constrained and non-constrained regions [29].

In recent mammalian genomics, phyloP scores derived from 240 placental mammal genomes have been used to define a base as significantly constrained at a phyloP score ≥ 2.27 (FDR 0.05), identifying 100 million bases (3.53%) of the human genome as functional [29]. This base-pair resolution constraint has proven more effective than other functional annotations for enriching disease heritability from GWAS.

Experimental Protocol: Detecting Constrained Bases with phyloP

Input Requirements: A whole-genome multiple sequence alignment in MAF (Multiple Alignment Format) and a species phylogenetic tree with branch lengths.

Workflow:

- Model Fitting: Estimate a neutral evolutionary model from fourfold degenerate sites in the alignment using the

phyloFitprogram. - Conservation Scoring: Run

phyloPwith the estimated model to compute conservation p-values for every base in the reference genome. - Threshold Application: Apply a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold (e.g., 5%) to define a set of significantly constrained bases.

Table: Key phyloP Parameters and Settings for Mammalian Constraint Analysis

| Parameter | Setting | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

--method |

LRT |

Uses likelihood ratio test for scoring conservation. |

--mode |

CON |

Computes conserved sites (use ACC for accelerated). |

--branch |

(Specified tree) | Specifies the species tree and branch lengths. |

--FDR |

0.05 |

Controls the false discovery rate for significance. |

Figure: Workflow for identifying evolutionarily constrained bases from a whole-genome alignment using the PHAST suite.

PAML (Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood)

PAML is a software package for maximum likelihood analysis of protein and DNA sequences. Its program CODEML is the gold standard for detecting positive selection acting on protein-coding genes by comparing nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitution rates, with a dN/dS ratio (ω) > 1 indicating positive selection [30].

Core Codon Models for Positive Selection

- Branch Models: Test for divergent selection pressures across phylogenetic lineages (e.g., foreground vs. background branches) [30] [25].

- Site Models: Detect positive selection affecting specific amino acid sites across all lineages in the phylogeny [30].

- Branch-site Models: Identify positive selection acting on a subset of sites along specific pre-defined lineages [30] [25].

Experimental Protocol: Branch-Site Test with CODEML

The branch-site test is frequently used to detect positive selection associated with a specific trait (e.g., longevity, migration) in a lineage of interest.

Input Requirements: A codon-aligned sequence file (FASTA format), a rooted species tree (Newick format) with foreground branch(es) labeled, and a control file (codeml.ctl).

Workflow:

- Tree Preparation: Label the branches of interest (e.g., long-distance migratory mammals) as the "foreground" in the tree file [25].

- Control File Configuration: Set up two

codemlruns for the null and alternative hypotheses of the branch-site test. - Model Execution: Run

CODEMLseparately for both the null and alternative models. - Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT): Compare the two model fits using the LRT statistic, 2Δℓ = 2(ℓalt - ℓnull), which follows a χ² distribution [30].

- Site Identification: For significant genes, use the Bayes Empirical Bayes (BEB) analysis to identify specific amino acid sites under positive selection with posterior probability > 0.80 or 0.95 [30] [25].

Table: Branch-Site Model Setup and Null Hypothesis Test

| Component | Null Model (ModelAnull) | Alternative Model (ModelA) |

|---|---|---|

| Codeml.ctl parameters | model = 2, NSsites = 2, fix_omega = 1, omega = 1 |

model = 2, NSsites = 2, fix_omega = 0, omega = 1.5 |

| Foreground branches ω | Fixed at ω = 1 (neutral) | Allowed to be ≥ 1 (can include positive selection) |

| LRT Interpretation | Significant result (p < 0.05) rejects the null, indicating positive selection on foreground branches. |

Figure: CODEML branch-site analysis workflow for detecting lineage-specific positive selection.

Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS)

Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) is a comparative method that tests for correlations between traits while accounting for non-independence of species due to shared evolutionary history [31]. It corrects for phylogenetic signal by incorporating the expected variance-covariance structure of residuals based on an evolutionary model and a phylogenetic tree.

Core Concepts and Applications

PGLS is a special case of generalized least squares where the error structure follows a multivariate normal distribution with a covariance matrix V derived from the phylogeny [31]. Common models for V include Brownian motion, Ornstein-Uhlenbeck, and Pagel's λ. PGLS has been instrumental in pan-mammalian studies of traits like longevity and body size, allowing researchers to identify genes whose evolutionary rates (e.g., dN/dS) correlate with traits across dozens of species [32].

Experimental Protocol: Correlating Evolutionary Rates with a Continuous Trait

Input Requirements: A species phylogeny with branch lengths, a continuous phenotype (e.g., maximum lifespan) for each species, and evolutionary rates for each gene of interest (e.g., dN/dS from CODEML).

Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Compile a dataset containing the trait values and gene evolutionary rates for all species in the phylogeny.

- Model Selection: Choose an evolutionary model for the covariance structure (e.g., Brownian motion).

- PGLS Regression: Fit a PGLS model for each gene, testing the association between its evolutionary rate and the trait.

- Significance Testing: Apply multiple testing correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg FDR) to identify significant associations [32].

A recent pan-mammalian analysis used this approach with relative evolutionary rates (RERs) and found that ~15% of genes showed significant correlations between their evolutionary rates and a longevity-body size trait, highlighting processes like DNA repair and immunity [32].

Table: PGLS Model Components for Trait-Gene Association Studies

| Component | Description | Example from Longevity Research |

|---|---|---|

| Response Variable | The evolutionary statistic for a gene (e.g., dN/dS, RER). | Relative evolutionary rate (RER) of a protein [32]. |

| Predictor Variable | The continuous trait of interest across species. | Maximum lifespan or a composite longevity-body size trait [32]. |

| Covariance Matrix (V) | Phylogenetic variance-covariance from a tree and model. | Brownian motion model of trait evolution [31]. |

| Biological Interpretation | A significant negative correlation suggests increased constraint in species with high trait values. | Genes for DNA repair show increased constraint (slower evolution) in long-lived species [32]. |

Figure: Logical workflow for a PGLS analysis testing associations between gene evolutionary rates and phenotypic traits across species.

Integrated Workflow in Mammalian Genomics

These tools are most powerful when used in an integrated fashion. A typical research pipeline might: 1) use phastCons to identify conserved non-coding elements; 2) apply CODEML to test protein-coding genes within these regions for positive selection; and 3) employ PGLS to correlate evolutionary rates of these candidate genes with quantitative phenotypes across the mammalian phylogeny.

Case Study: Uncovering the Genetics of Long-Distance Migration

A recent study of long-distance migratory mammals exemplifies this integrated approach [25]. Researchers:

- Alignment & Orthology: Constructed a codon-level alignment of 11,308 orthologous genes from 52 mammalian species.

- Selection Tests: Used

CODEMLbranch-site models to detect positive selection in 21 migratory species, with a stringent significance threshold (corrected p-value < 0.01). - Accelerated Evolution: Applied

CODEMLbranch models to identify genes with accelerated evolution (ω) in the migratory lineage. - Trait Correlation: Conducted PGLS regression of root-to-tip ω values against migratory status, identifying genes whose evolutionary rates correlate with this behavior.

This multi-pronged analysis revealed genes under selection involved in memory, sensory perception, and energy metabolism—key biological systems for long-distance migration [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key bioinformatics resources and datasets essential for conducting evolutionary constraint analyses in mammals.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Mammalian Evolutionary Genomics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Source/Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zoonomia Alignment | Genomic Data | A multiple genome alignment of 240 placental mammals; the primary dataset for calculating mammalian constraint [29] [25]. | Zoonomia Project |

| PHAST Software Suite | Software Tool | Calculates base-wise conservation (phyloP) and identifies conserved elements (phastCons) from genome alignments [29]. |

http://compgen.cshl.edu/phast/ |

| PAML Software Package | Software Tool | Performs maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis, including detection of positive selection with CODEML [30]. |

http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk/software/paml.html |

| TimeTree Database | Web Resource | Provides pre-calculated phylogenetic trees and divergence times for constructing species trees in PAML/PGLS [25]. | http://timetree.org/ |

| AnAge Database | Phenotypic Data | A curated database of animal ageing and life history data, essential for obtaining traits like maximum lifespan for PGLS [33] [32]. | https://genomics.senescence.info/species/ |

The integrated use of PHAST, PAML, and PGLS provides a robust statistical framework for deciphering evolutionary constraint and adaptation from genomic data. As exemplified by recent large-scale mammalian studies, these tools can pinpoint constrained functional elements, reveal genes under positive selection, and correlate evolutionary patterns with complex traits like longevity and migration. For drug development professionals, this toolkit offers a powerful approach for prioritizing disease-associated genes and understanding the fundamental genetic constraints that shape human health and disease. Continued development of these methods, coupled with ever-larger genomic datasets, promises to further illuminate the molecular basis of mammalian evolution and phenotypic diversity.

Identifying Lineage-Specific Accelerated Evolution in Coding and Non-Coding Regions

The identification of lineage-specific accelerated regions represents a cornerstone of modern comparative genomics, sitting at the intersection of evolutionary constraint and adaptive innovation. The core premise of evolutionary constraint posits that functional genomic elements—both coding and non-coding—are preserved across deep evolutionary timescales due to purifying selection. However, certain lineages experience periods of rapid, accelerated evolution in specific genomic elements, potentially underlying the emergence of novel phenotypic traits. This technical guide examines the methodologies for identifying these accelerated regions, the quantitative patterns distinguishing mammalian and avian lineages, and the experimental frameworks for validating their functional significance. The field has progressed from focusing exclusively on protein-coding sequences to encompassing regulatory elements, recognizing that changes in gene regulation often constitute the primary drivers of morphological evolution [10].

The conceptual foundation rests on detecting sequences that are highly conserved across broad phylogenetic groups (indicating functional importance) yet show significantly elevated substitution rates along particular lineages (suggesting positive selection). This approach has revealed genetic elements potentially responsible for defining mammalian characteristics like dentition, hair development, and high-frequency hearing, as well as avian features such as flight feathers and respiratory adaptations [10]. Contemporary studies leverage increasingly comprehensive genome alignments—such as the Zoonomia project's 240-species alignment for mammals and the B10K project's 363 avian genomes—to achieve unprecedented resolution in detecting these evolutionary signatures [10].

Computational Identification of Accelerated Regions

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

Lineage-specific accelerated regions are genomic elements that have undergone significantly accelerated evolutionary rates in a specific lineage compared to background neutral evolution. These are categorized as:

- Coding Accelerated Regions (cARs): Accelerated elements overlapping protein-coding exons, potentially affecting protein structure and function.

- Non-coding Accelerated Regions (ncARs): Accelerated elements in regulatory regions, including enhancers, promoters, and other cis-regulatory elements, potentially altering gene expression patterns [10].

The fundamental assumption is that sequences functional in gene regulation remain significantly more conserved than non-functional DNA across evolutionary timescales, while lineage-specific acceleration signals potential adaptive evolution [10].

Core Methodological Pipeline

The standard workflow for identifying lineage-specific accelerated regions integrates several bioinformatic tools and analytical steps:

Step 1: Genome Alignment and Conservation Detection

- Input: Multi-species whole-genome alignments spanning the target lineage and appropriate outgroups.

- Process: Identify deeply conserved sequences using programs like phastCons from the PHAST package [10].

- Parameters: Typically requires minimum sequence length (e.g., 100bp) and conservation across broad phylogenetic spectra.

- Output: Set of conserved non-coding elements (CNEs) or other conserved genomic regions.

Step 2: Acceleration Detection

- Process: Apply acceleration detection algorithms like phyloP (from the PHAST package) to conserved sequences identified in Step 1 [10].

- Parameters: Test for substitution rates significantly faster than neutral expectation across specific lineage branches.

- Lineage Specification: For mammalian accelerated regions (MARs), include basal mammals like platypus to distinguish mammalian-specific changes. For avian accelerated regions (AvARs), include early-diverging birds like tinamou or ostrich [10].

- Output: Catalog of lineage-specific accelerated regions with statistical significance measures.

Step 3: Functional Annotation

- Process: Annotate accelerated regions with genomic context (coding/non-coding), proximity to genes, overlap with regulatory marks (e.g., ENCODE ChIP-seq data), and transcription factor binding motifs.

- Validation: Select candidate regions for experimental validation of regulatory potential.