Environmental DNA Bioinformatics Pipelines: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of environmental DNA (eDNA) bioinformatics pipelines, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Environmental DNA Bioinformatics Pipelines: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of environmental DNA (eDNA) bioinformatics pipelines, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts, from basic workflows to the range of available software, and delves into methodological applications, including specialized pipelines for marine and terrestrial biomonitoring. The guide addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to minimize false positives and negatives, and offers a comparative analysis of pipeline performance for validation. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this resource aims to empower professionals in selecting, implementing, and validating eDNA bioinformatic workflows to advance biomedical discovery, pathogen surveillance, and bioprospecting efforts.

Demystifying eDNA Bioinformatics: Core Concepts and Pipeline Diversity

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive biomonitoring tool that enables multi-taxa identification from environmental samples such as water and soil [1]. This technique has demonstrated particular superiority over traditional ecological methods for surveying freshwater fish communities, offering higher sensitivity for detecting elusive species and achieving greater overall taxonomic coverage [1] [2]. The successful implementation of eDNA metabarcoding hinges upon a series of interconnected steps, from initial sample collection through computational analysis, with choices at each stage significantly influencing biodiversity outcomes [2]. This application note provides a detailed protocol for conducting comprehensive eDNA metabarcoding studies, with special emphasis on bioinformatic pipeline selection and its impact on biological interpretation.

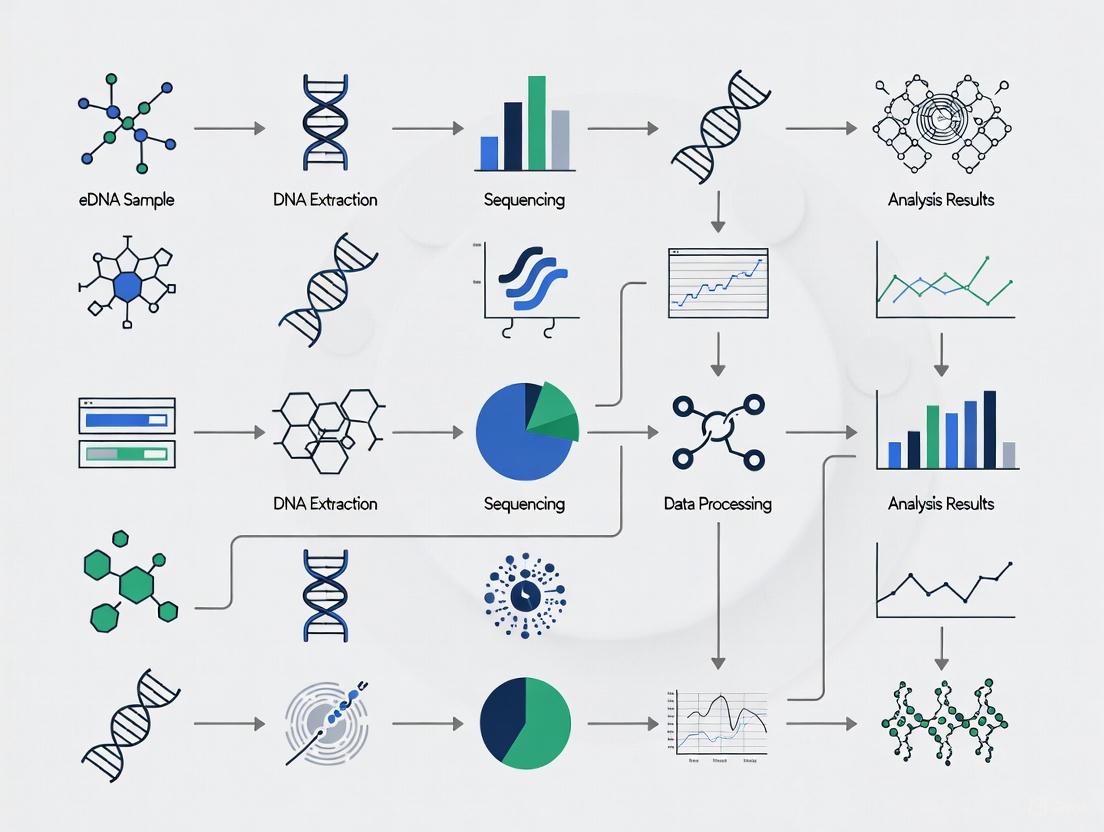

The eDNA metabarcoding workflow encompasses multiple phases: experimental design, sample collection, DNA extraction, library preparation, high-throughput sequencing, bioinformatic processing, and taxonomic assignment [2]. The following sections detail each critical step, with experimental protocols and bioinformatic considerations specifically framed within the context of eDNA bioinformatics pipelines research.

Figure 1: Complete eDNA metabarcoding workflow from sample collection to data interpretation. Orange boxes represent wet-lab procedures, while green boxes indicate bioinformatic steps. The red subgraph details the specific stages within bioinformatic processing.

Sample Collection & Processing Protocols

Sample Collection Methods

Water Sampling for Aquatic Ecosystems:

- Collect water samples using sterile containers or specialized eDNA filtration systems

- Filter appropriate water volumes (typically 1-2 liters) through membranes with 0.8-1.2 μm pore sizes [3]

- Preserve filters in appropriate buffer solutions (e.g., Longmire's buffer, ethanol) and store at -20°C until DNA extraction

- Include field negative controls (e.g., purified water processed alongside environmental samples) to monitor contamination

Specimen-Based Sampling for Macroinvertebrates:

- Live-sorting approach: Manually sort organisms from debris, preserving specimens in 96% ethanol at -20°C [3]

- Soft-lysis protocol: Non-destructive DNA extraction allowing morphological verification post-analysis [3]

- Aggressive-lysis protocol: Destructive homogenization for maximal DNA yield [3]

- Unsorted-debris protocol: Homogenize entire sample including substrate and plant material [3]

Comparative Performance of Sampling Methods

Table 1: Comparison of sampling protocol efficiency for macroinvertebrate monitoring based on peatland ditch samples [3]

| Sampling Protocol | Community Similarity to Morphology | Taxonomic Bias | Processing Time | Morphological Verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive-lysis | 70 ± 6% | Low | Moderate | Not possible |

| Soft-lysis | 58 ± 7% | Moderate (misses some beetles) | Moderate | Possible |

| Unsorted-debris | 31 ± 9% | High | Fast | Not possible |

| Water eDNA | 20 ± 9% | Very high | Fast | Not possible |

Laboratory Processing & Sequencing

DNA Extraction and Amplification

DNA Extraction Protocols:

- Utilize commercial extraction kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil, QIAamp) optimized for environmental samples

- Include extraction blank controls to monitor kit contamination

- For soft-lysis approaches: incubate intact specimens in lysis buffer (typically 4-24 hours) without physical disruption [3]

PCR Amplification:

- Select appropriate genetic markers:

- Incorporate dual indexing to minimize index hopping in multiplexed sequencing

- Perform multiple PCR replicates to address stochastic amplification

- Include positive controls (mock communities) and negative PCR controls

Sequencing Platform Selection

Table 2: Comparison of sequencing platforms for eDNA metabarcoding applications

| Platform | Chemistry | Read Length | Error Profile | Bioinformatic Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Reversible dye terminators | Short-read (75-300 bp) | Low error rate, predominantly substitutions | DADA2 error models optimized for this platform [1] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing | Short-read (up to 400 bp) | Higher indels, especially in homopolymers | Requires parameter adjustment for homopolymer regions [1] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | Long-read (potentially >10 kb) | Higher error rate, random errors | Enables near full-length marker sequencing [4] |

| PacBio SMRT | Circular consensus sequencing | Long-read with high accuracy | Low error rate after CCS | Suitable for full-length barcode sequencing [4] |

Bioinformatic Analysis

Pipeline Selection and Comparison

Bioinformatic processing represents a critical phase where raw sequencing data is transformed into biologically meaningful information. Multiple pipelines have been developed, each employing different algorithms for key steps including sequence inference (OTUs vs. ASVs) and taxonomic assignment.

Figure 2: Bioinformatic decision points in eDNA metabarcoding analysis. Red elements indicate critical algorithm choices that significantly impact biological interpretation.

Sequence Inference Methods

OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) Clustering:

- Groups sequences by similarity threshold (typically 97%)

- Uparse algorithm: Widely used for OTU clustering; mitigates overestimation of diversity from sequencing errors [2]

- Limitations: Can produce misclassification, nested sequences, and expansion of taxonomic number [2]

ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) Inference:

- DADA2: Achieves single-nucleotide resolution through error modeling and sequence correction [1] [2]

- Provides higher resolution than OTU methods but may reduce detected taxon numbers [2]

ZOTU (Zero-radius OTU) Denoising:

- UNOISE3: Outputs biologically meaningful sequences without clustering [2]

- Similar to ASV approach in providing high resolution

Performance Comparison of Bioinformatic Pipelines

Table 3: Comparative analysis of five bioinformatic pipelines for fish eDNA metabarcoding data [1] [2]

| Pipeline | Sequence Inference | Taxonomic Assignment | Key Features | Ecological Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacapa | DADA2 (ASVs) | BLCA (Bayesian method) | Combines ASV inference with Bayesian classification | High similarity in alpha/beta diversity across pipelines [1] |

| Barque | No clustering (read annotation) | VSEARCH (global alignment) | Alignment-based taxonomy without clustering | Consistent taxa detection with increased sensitivity [1] |

| metaBEAT | VSEARCH (OTUs) | BLAST (local alignment) | Creates OTUs through VSEARCH | Similar ecological interpretation despite methodological differences [1] |

| MiFish | Custom workflow | BLAST-based alignment | Specifically designed for MiFish primers | Mantel test shows significant similarity between pipelines [1] |

| SEQme | Modified workflow | RDP (Bayesian classifier) | Sequence merging before trimming; machine learning approach | Choice of pipeline does not significantly affect ecological interpretation [1] |

Table 4: Impact of sequence inference methods on diversity metrics in fish eDNA metabarcoding [2]

| Bioinformatic Method | Algorithm Type | Effective Sequences | Detected Taxa | Community Composition Correlation | Impact on Diversity-Environment Relationships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTU (Uparse) | Similarity clustering (97%) | 43,288 | Higher | Lower similarity to morphology | Overestimation potential |

| ZOTU (UNOISE3) | Denoising algorithm | 49,561 | Intermediate | Intermediate similarity | Moderate underestimation |

| ASV (DADA2) | Error model-based | 37,912 | Lower | Higher resolution | Possible underestimation of correlations [2] |

Taxonomic Assignment Approaches

Conventional Methods

Alignment-Based Approaches:

- BLAST: Local alignment-based tool; accurate but computationally intensive [1] [4]

- VSEARCH: Global alignment implementation; faster than BLAST with similar accuracy [1]

Bayesian Classifiers:

- RDP Classifier: Naïve Bayesian approach; faster than alignment methods but faces scalability challenges [4]

- BLCA: Bayesian lowest common ancestor method; requires no training step, relies on reference database alignment [1]

Emerging Machine Learning Approaches

DeepCOI Framework:

- Implements large language model (LLM) for taxonomic assignment of COI sequences [4]

- Employs hierarchical multi-label classification from phylum to species level

- Performance advantages: AU-ROC of 0.958 and AU-PR of 0.897, outperforming existing methods [4]

- Efficiency: Approximately 4x faster than RDP classifier and 73x faster than BLAST [4]

- Effectively handles congeneric species through weighted BCELoss accounting for ancestral labels

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential research reagents and computational tools for eDNA metabarcoding

| Category | Item | Specification/Version | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | DNA Extraction Kit | DNeasy PowerSoil, QIAamp | Environmental DNA isolation and purification |

| PCR Primers | 12S rRNA, COI, 16S rRNA | Target-specific amplification of barcode regions | |

| Ethanol | 96% | Sample preservation and soft-lysis protocols [3] | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | DADA2 | Latest version | ASV inference incorporating platform-specific error models [1] |

| VSEARCH | Current build | Sequence clustering and alignment-based taxonomy [1] | |

| BLAST+ | Updated versions | Local alignment for taxonomic assignment [1] | |

| DeepCOI | Pre-trained model | LLM-based taxonomic classification of COI sequences [4] | |

| Reference Databases | BOLD | Version 4+ | Curated COI reference database for animal species [4] |

| SILVA, Greengenes | Latest releases | Ribosomal RNA databases for 12S/16S assignments | |

| Custom databases | Study-specific | Curated databases for particular taxonomic groups |

The eDNA metabarcoding workflow represents an integrated system where choices at each stage—from sample collection through bioinformatic analysis—significantly impact final biodiversity assessments. While bioinformatic pipeline selection influences specific outcomes such as community composition and diversity metrics, recent comparative studies indicate that ecological interpretation remains consistent across major pipelines [1]. For researchers designing eDNA studies, we recommend: (1) selecting sampling protocols based on compatibility with traditional methods versus processing efficiency requirements [3]; (2) utilizing ASV-based approaches for high-resolution data [2]; and (3) considering emerging machine learning classifiers like DeepCOI for enhanced accuracy and efficiency in taxonomic assignment [4]. As the field advances, standardization of protocols and continued benchmarking of bioinformatic tools will further strengthen the application of eDNA metabarcoding in environmental monitoring and ecosystem assessment.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has revolutionized biodiversity monitoring, enabling non-invasive, multi-taxa identification from environmental samples such as water, soil, and air [1]. The successful implementation of eDNA metabarcoding hinges upon bioinformatic pipelines that transform raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful information. These pipelines perform a series of computational steps including sequence demultiplexing, quality filtering, chimera removal, clustering or denoising, and taxonomic assignment [1]. The landscape of available pipelines has expanded dramatically, creating both opportunities and challenges for researchers seeking to implement robust, reproducible amplicon analysis.

The choice between Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) represents a fundamental methodological division in pipeline design. OTU-based approaches cluster sequences based on a defined similarity threshold (typically 97%), while ASV-based methods employ denoising algorithms to distinguish biological sequences from sequencing errors at single-nucleotide resolution [2] [5]. This distinction profoundly influences downstream ecological interpretations, with ASVs offering higher taxonomic resolution and cross-study comparability, while OTUs may provide more robust clustering for markers with high intragenomic variation, such as fungal ITS regions [6].

Table 1: Core Methodological Approaches in Amplicon Processing

| Approach | Definition | Key Algorithms | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTU Clustering | Groups sequences based on similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) | UCLUST, VSEARCH, OptiClust, UPARSE | Fungal ITS analysis, 16S rRNA gene studies with high intragenomic variation |

| ASV Denoising | Infers biological sequences using error models | DADA2, UNOISE3, Deblur | High-resolution biodiversity studies, strain-level differentiation |

| Alignment-based Taxonomy | Assigns taxonomy using sequence alignment to reference databases | BLAST, VSEARCH global alignment | Verifying specific species detections, curated reference databases |

| Machine Learning Taxonomy | Employs classifiers trained on reference databases | RDP Bayesian classifier, SINTAX | High-throughput assignments, well-established reference databases |

The following section provides a comprehensive overview of documented amplicon processing pipelines, highlighting their methodological foundations, key features, and applicability to eDNA research.

Table 2: Overview of Amplicon Processing Pipelines

| Pipeline Name | Core Methodology | Key Features | Target Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacapa | ASV inference (DADA2), BLCA taxonomy | Modular design, detailed documentation | Fish eDNA metabarcoding, general purpose | [1] |

| Barque | Read annotation, alignment-based taxonomy | No OTU/ASV clustering, VSEARCH global alignment | Direct read assignment, vertebrate detection | [1] |

| metaBEAT | OTU clustering (VSEARCH), BLAST taxonomy | Similar to Barque but with OTU creation | General eDNA metabarcoding | [1] |

| MiFish | BLAST-based taxonomy | Specialized for fish-specific 12S markers | Fish diversity assessment, marine ecosystems | [1] |

| SEQme | Machine learning taxonomy (RDP) | Sequence merging before trimming | Alternative workflow organization | [1] |

| DADA2 | ASV inference via error model | Single-nucleotide resolution, R package | High-resolution community profiling | [2] [6] |

| UNOISE3 (UPARSE) | ZOTU inference via abundance filtering | Denoising, chimera removal, USEARCH implementation | Noise reduction in complex communities | [2] |

| mothur | OTU clustering (OptiClust) | Fully transparent workflow, command-line tool | Microbial ecology, fungal ITS analysis | [6] |

| REVAMP | ASV inference (DADA2), BLAST taxonomy | Automated visualization, cloud-based options | NOAA observatories, marine biodiversity | [7] |

| Dix-seq | Containerized, modular design | Single-command processing, parameter sheet | Custom analysis, entry-level users | [8] |

| QIIME 2 | Multiple methods (DADA2, Deblur, VSEARCH) | Extensive plugins, user-friendly interface | General purpose microbiome analysis | [5] |

| FROGS | OTU clustering | PHYLOSEQ compatibility, SWARM algorithm | Standardized microbial ecology | [9] |

| OCToPUS | Multiple clustering methods | Customizable workflow, benchmarking tools | Method comparison studies | [9] |

| PEMA | Flexible framework | Multiple aligners, reproducible research | Cross-platform compatibility | [9] |

| AmpliconTagger | Hybrid approach | Combines different methodological elements | Verification through multiple approaches | [9] |

Additional pipelines referenced in the literature but not detailed in the search results include MED, Deblur, UCLUST, FROGS, Natrix, MicrobiomeAnalyst, AmpliconTagger, PEMA, OCToPUS, USEARCH, VSEARCH-based custom pipelines, SILVAngs, and Kraken 2, bringing the total well beyond the 32+ pipelines mentioned in the title. This diversity underscores the highly active development field and the absence of a single gold-standard approach [9].

Comparative Performance and Ecological Interpretation

Methodological Comparisons and Benchmarking Studies

Rigorous comparisons of bioinformatic pipelines are essential for assessing their reliability and suitability for specific research applications. A study comparing five pipelines (Anacapa, Barque, metaBEAT, MiFish, and SEQme) on fish eDNA from Czech reservoirs found consistent taxa detection across pipelines, with alpha and beta diversities exhibiting significant similarities. The key conclusion was that the choice of bioinformatic pipeline did not significantly affect metabarcoding outcomes or their ecological interpretation [1].

However, other studies reveal important nuances. Research in the Pearl River estuary demonstrated that different pipelines (Uparse/OTU, UNOISE3/ZOTU, and DADA2/ASV) can influence biological interpretation, with denoising algorithms (DADA2, UNOISE3) potentially reducing the number of detected taxa and affecting correlations with environmental factors [2]. For fungal ITS data, performance differences emerge clearly, with mothur identifying higher fungal richness compared to DADA2 at a 99% similarity threshold. Additionally, mothur generated more homogeneous relative abundances across technical replicates, while DADA2 results showed higher heterogeneity [6].

A comprehensive benchmarking of 16S rRNA algorithms using a complex mock community of 227 bacterial strains revealed that ASV algorithms (particularly DADA2) produced consistent output but suffered from over-splitting, while OTU algorithms (especially UPARSE) achieved clusters with lower errors but more over-merging [10]. Both UPARSE and DADA2 showed the closest resemblance to the intended microbial community structure in alpha and beta diversity measures [10].

Robustness and Reproducibility Considerations

The reproducibility of bioinformatic results across different pipelines is a critical concern. A reprocessing study of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing data from oral microbiome studies found that while four mainstream pipelines (VSEARCH, USEARCH, mothur, and UNOISE3) generally provided similar results, P-values sometimes differed between pipelines beyond significance thresholds [9]. This highlights the disconcerting reality that statistical conclusions can be pipeline-dependent, potentially altering biological interpretations.

Only 57% of articles with deposited data made all sequencing and metadata available, hampering reproducibility efforts. Issues were frequently encountered due to read characteristics, tool differences, and lack of methodological detail in articles [9]. These findings underscore the importance of detailed methods reporting and data sharing for reproducible amplicon sequencing research.

Experimental Protocols for Pipeline Comparison

Protocol 1: Cross-Pipeline Validation Using Mock Communities

Purpose: To evaluate the performance of different amplicon processing pipelines using DNA from a mock community of known composition.

Materials and Reagents:

- Mock Community DNA: Comprising genomic DNA from 227 bacterial strains (HC227) or other validated mock communities [10]

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina MiSeq for 2×300 bp paired-end reads [10]

- Quality Assessment Tool: FastQC (v.0.11.9) for initial sequence quality check [10]

- Primer Removal Tool: cutPrimers (v.2.0) for stripping primer sequences [10]

- Read Processing Tools: USEARCH (v.11.0.667) for read merging, PRINSEQ (v.0.2.4) for length trimming [10]

- Reference Database: SILVA (Release 132) for orientation checking [10]

Experimental Procedure:

- Sequence Generation: Amplify the mock community targeting appropriate variable regions (e.g., V3-V4 for 16S rRNA) and sequence on Illumina platform [10]

- Data Preprocessing: Subsample to 30,000 reads per sample to standardize sequencing depth [10]

- Parallel Processing: Process identical datasets through multiple pipelines (e.g., DADA2, UNOISE3, UPARSE, mothur) using standardized parameters [10]

- Error Rate Calculation: Compare output sequences to expected composition to calculate false positive and false negative rates [10]

- Diversity Assessment: Calculate alpha and beta diversity metrics from each pipeline and compare to expected values [10]

- Over-merging/Splitting Analysis: Assess whether pipelines incorrectly merge distinct sequences or split genuine biological variants [10]

Protocol 2: Ecological Validation Using Field Samples

Purpose: To assess how pipeline choice influences ecological interpretation of field-collected eDNA samples.

Materials and Reagents:

- Field Samples: eDNA from water, soil, or air samples collected from environmentally characterized sites [1] [2]

- Positive Controls: DNA from known species added to samples to monitor detection sensitivity [1]

- Negative Controls: Extraction and PCR blanks to identify contamination [1]

- Traditional Survey Data: Parallel conventional ecological surveys (e.g., trawling, visual transects) for validation [2]

Experimental Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect eDNA samples from designated sites following standardized protocols [1]

- DNA Extraction: Extract eDNA using appropriate kits for the sample matrix [6]

- Library Preparation: Amplify target genes (e.g., 12S rRNA for fish, ITS for fungi) and prepare sequencing libraries [1] [6]

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on Illumina or other platforms [1]

- Multi-Pipeline Analysis: Process data through at least three different pipeline types (OTU-based, ASV-based, alignment-based) [1] [2]

- Comparative Metrics: Calculate and compare alpha diversity, beta diversity, Mantel tests, and taxa detection across pipelines [1]

- Ecological Correlation: Assess how pipeline outputs correlate with environmental variables and traditional survey data [2]

Visualization of Pipeline Workflows and Method Selection

Logical Workflow of a Generic Amplicon Processing Pipeline

Decision Framework for Pipeline Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Amplicon Processing

| Category | Item | Specification/Version | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | NucleoSpin Soil Kit | Macherey-Nagel | DNA extraction from environmental samples |

| ¼ Ringer + Tween 80 solution | 0.01% (v/v) | Soil slurry preparation for DNA extraction | |

| PCR primers | Species-specific (e.g., 12S for fish) | Target gene amplification | |

| Mock Community DNA | HC227 (227 bacterial strains) | Pipeline validation and benchmarking | |

| Reference Databases | SILVA database | Release 132+ | rRNA reference for taxonomy assignment |

| NCBI nt database | Current version | Comprehensive taxonomy assignment | |

| Greengenes | 13_8 (or current) | 16S rRNA gene reference | |

| Barcode of Life Database | Current version | Species-level identification | |

| Computational Tools | FastQC | v.0.11.9+ | Initial sequence quality assessment |

| Cutadapt | v.1.18+ | Primer and adapter removal | |

| DADA2 | R package | ASV inference via error modeling | |

| mothur | v.1.41.3+ | OTU clustering and analysis | |

| VSEARCH | v.2.11.0+ | Open-source alternative to USEARCH | |

| QIIME 2 | Current version | Integrated microbiome analysis | |

| Statistical Frameworks | R vegan package | Current version | Ecological diversity analysis |

| phyloseq | R package | Microbiome data visualization | |

| PERMANOVA | Statistical testing of group differences |

The landscape of amplicon processing pipelines is diverse and continually evolving, with different tools offering distinct advantages for specific research applications. While consistency across pipelines has been demonstrated in some studies, particularly for fish eDNA metabarcoding [1], important differences in biological interpretation can emerge from alternative processing approaches [2]. The fundamental division between OTU and ASV methodologies represents not merely technical alternatives but different philosophical approaches to handling biological variation and sequencing error.

Future developments will likely focus on improved standardization, benchmarking, and reproducibility. Tools like REVAMP [7] and Dix-seq [8] represent moves toward more automated, reproducible workflows. The emergence of long-read sequencing technologies [11] and novel analysis approaches like micov for differential coverage analysis [12] will further expand the analytical toolbox available to researchers.

Critical considerations for pipeline selection include marker gene characteristics, required taxonomic resolution, computational resources, and research objectives. For fungal ITS analysis, OTU-based approaches may be preferable [6], while ASV methods excel when single-nucleotide resolution is required [5]. Ultimately, researchers should validate their chosen pipeline using mock communities and report methodological details with sufficient precision to enable reproduction and comparison across studies.

In environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding research, the bioinformatic processing of raw sequencing data into meaningful biological units is a critical step that significantly influences downstream ecological interpretations [1] [2]. The scientific community has primarily adopted two philosophical approaches for this: the established method of clustering into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and the more recent method of denoising to resolve Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Zero-radius OTUs (ZOTUs) [13] [14]. The choice between these methods directly impacts the resolution of biodiversity data, affecting the detection of rare species, estimates of alpha diversity, and the accuracy of taxonomic assignments [15] [2]. Understanding the conceptual and practical distinctions between these approaches is therefore essential for designing robust eDNA bioinformatics pipelines, particularly in applied contexts such as biomonitoring and invasive species detection [16].

This application note provides a structured comparison of OTU clustering and ASV denoising, detailing their underlying principles, respective workflows, and practical performance. It is framed within the context of developing standardized eDNA bioinformatic protocols for reproducible research in aquatic ecosystems.

Conceptual Foundations: OTUs, ASVs, and ZOTUs

Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) via Clustering

The OTU approach is based on clustering sequences together based on a predefined similarity threshold, traditionally 97% for bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA genes [17]. This method operates on the idea that sequencing errors are rare and that clustering will minimize their impact by grouping erroneous sequences with their correct, more abundant "mother" sequence [13] [17]. An OTU is thus an abstracted consensus of a cluster of similar sequences.

- Reference-free (de novo) Clustering: Clusters sequences without a reference database. It is computationally expensive and results are study-dependent, as the same sequence may cluster differently when new data is added [17].

- Reference-based (closed-reference) Clustering: Compares sequences to a pre-existing reference database. It is computationally fast and allows for easy cross-study comparison but will discard sequences not present in the database, leading to a loss of novel diversity [17].

- Open-reference Clustering: A hybrid approach that first clusters sequences against a reference database (like closed-reference) and then clusters the remaining sequences de novo. This aims to balance computational efficiency with the retention of novel sequences [17].

Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and ZOTUs via Denoising

In contrast to clustering, denoising attempts to correct sequencing errors to identify biologically real sequences at single-nucleotide resolution [15]. The results are called Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or, when using the UNOISE3 algorithm, Zero-radius OTUs (ZOTUs) [13] [14]. These terms are often used interchangeably to refer to exact biological sequences inferred from the data.

- DADA2 (ASVs): Uses a parametric error model trained on the entire sequencing run to distinguish between true biological sequences and those generated by sequencing errors [15] [2].

- UNOISE3 (ZOTUs): Employs a one-pass clustering strategy that does not depend on quality scores but rather on pre-set parameters to discard sequences believed to be errors [15].

Denoising does not rely on arbitrary similarity thresholds and produces units that are reproducible and directly comparable across studies, as a given biological sequence will always result in the same ASV [17] [15].

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Trade-offs

The choice between clustering and denoising involves significant trade-offs that can influence the biological interpretation of eDNA metabarcoding data.

Table 1: Conceptual and Practical Trade-offs between Clustering and Denoising

| Aspect | OTU Clustering (e.g., VSEARCH) | ASV Denoising (e.g., DADA2, UNOISE3) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Clusters sequences based on a % similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) [13] [17]. | Infers exact biological sequences by correcting sequencing errors [17] [15]. |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Lower resolution; may lump multiple species into one OTU or split one species into multiple OTUs [13] [17]. | Higher resolution; can distinguish intra-species genetic variation, potentially to the haplotype level [17] [14]. |

| Reproducibility & Cross-study Comparison | Low for de novo; Clusters are study-specific. High for closed-reference if the same database is used [17]. | High; ASVs are exact sequences, making them portable and comparable across studies [17] [15]. |

| Handling of Sequencing Errors | Mitigates errors by clustering them with abundant sequences [17]. | Explicitly models and removes errors [15]. |

| Sensitivity to Rare Taxa | Can retain rare sequences but at the cost of also retaining spurious OTUs [17]. | DADA2 is highly sensitive to rare sequences, though this may increase false positives; UNOISE3 is more conservative [15]. |

| Dependence on Reference Databases | Required for closed-reference, bypassed for de novo [17]. | Denoising is reference-free; taxonomic assignment afterward requires a database [14]. |

| Computational Demand | De novo is computationally intensive; closed-reference is fast [17]. | DADA2 is computationally demanding; UNOISE3 is very fast [15]. |

Table 2: Empirical Comparison of Pipeline Outputs from a Fish eDNA Study Data adapted from a study in the Pearl River Estuary, which compared outputs from three pipelines on the same dataset [2].

| Pipeline (Method) | Number of Effective Features | Number of Detected Fish Taxa | Key Characteristics in Fish Community Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| UPARSE (OTU) | 43,288 | 66 | Produced the highest alpha diversity. More sensitive to environmental factors. Better for revealing community patterns under environmental pressure [2]. |

| UNOISE3 (ZOTU) | 49,561 | 68 | Detected more fish taxa than OTU. Showed the best performance in separating fish community compositions in Beta diversity analysis [2]. |

| DADA2 (ASV) | 36,102 | 63 | Produced the fewest features and taxa. Resulted in underestimation of the correlation between community composition and environmental factors [2]. |

Complementary Workflow: Denoising and Clustering

While often presented as alternatives, evidence suggests that denoising and clustering are complementary, particularly for highly variable markers like the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene used in metazoan metabarcoding [14]. The high intraspecies variability of COI contains valuable phylogeographic information that is lost if sequences are clustered at a 97% threshold but can be preserved by a combined approach.

The following workflow, implemented with VSEARCH, illustrates a protocol that incorporates both denoising and clustering steps for a comprehensive analysis.

Diagram 1: A Combined Denoising and Clustering Bioinformatics Workflow. The workflow proceeds through quality control and denoising as a primary path, with an optional secondary clustering step to generate species-level units from the denoised sequences.

Detailed Wet-Lab and In Silico Protocol

This protocol outlines the key steps for processing eDNA metabarcoding data, from sample collection to the generation of a feature table.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

| Category | Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Universal Metabarcoding Primers (e.g., 12S, COI) | Amplify short, variable gene regions from a wide range of target taxa in a single reaction [1] [16]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Reduces PCR errors during library amplification. | |

| Negative Control (PCR-grade Water) | Monitors for contamination during lab processing [1]. | |

| Positive Control (Mock Community) | A defined mix of DNA from known species, essential for validating bioinformatic pipeline performance [15] [18]. | |

| Bioinformatic Software | VSEARCH | A versatile open-source tool for processing sequence data; used for dereplication, denoising, clustering, and chimera detection [13]. |

| DADA2 (R Package) | A denoising pipeline that uses a parametric error model to infer ASVs [1] [15]. | |

| USEARCH (UNOISE3) | A algorithm for denoising that generates ZOTUs via a one-pass clustering strategy [14] [15]. | |

| QIIME 2 | A powerful, modular platform for managing and executing metabarcoding analysis pipelines [15]. | |

| Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes (16S) | Curated databases of ribosomal RNA genes for taxonomic assignment of prokaryotes. |

| MIDORI, BOLD (COI) | Curated databases of the COI gene for taxonomic assignment of eukaryotes [1]. |

Experimental Procedure:

Sample Collection & DNA Extraction:

- Collect water samples using sterile techniques to prevent contamination.

- Filter water through fine-pore filters (e.g., 0.22µm) to capture eDNA.

- Extract DNA from filters using a commercial eDNA or soil extraction kit, including both negative and positive controls in each extraction batch [16].

Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- Amplify the target genetic marker (e.g., 12S rRNA for fish, COI for invertebrates) using well-established primer sets [1] [16].

- Attach dual indices and sequencing adapters in a subsequent PCR step.

- Purify the final library and quantify accurately. Pool libraries in equimolar ratios and sequence on an Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq platform to generate paired-end reads [16].

Bioinformatic Processing (In Silico):

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequences to samples based on their unique index combinations.

- Quality Filtering & Trimming: Use a tool like

cutadaptto remove primers and adapter sequences. Trim low-quality bases from read ends based on quality scores [13] [15]. - Dereplication: Combine identical sequences into a single unique sequence while retaining abundance information using

vsearch --derep_fulllength[13]. - Denoising: Apply a denoising algorithm to correct errors.

- Using VSEARCH:

vsearch --cluster_unoise sorted_combined.fasta --sizein --sizeout --centroids centroids.fasta[13]. - This step produces a set of error-corrected sequences (ZOTUs).

- Using VSEARCH:

- Chimera Removal: Remove chimeric sequences formed during PCR.

- Using VSEARCH:

vsearch --uchime3_denovo centroids.fasta --nonchimeras otus.fasta[13].

- Using VSEARCH:

- (Optional) Clustering: Cluster the denoised sequences to generate species-level units.

- Using VSEARCH:

vsearch --cluster_size otus.fasta --centroids cluster_otus.fasta --id 0.97 --sizeout[13].

- Using VSEARCH:

- Construct Feature Table: Map all quality-filtered reads back to the final set of representative sequences (ZOTUs or OTUs) to create a frequency table.

- Using VSEARCH:

vsearch --usearch_global ../data/fasta/combined.fasta --db otus.fasta --id 0.9 --otutabout otu_frequency_table.tsv[13].

- Using VSEARCH:

The decision to use OTU clustering, ASV denoising, or a combined approach should be guided by the research question, the genetic marker used, and the state of reference databases. Denoising provides superior resolution and reproducibility, making it ideal for tracking specific haplotypes or strains and for cross-study comparisons. Clustering remains a useful method for generating species-level units, especially for markers with high and biologically meaningful intraspecific variation like COI [14].

For eDNA studies targeting fish and other metazoans with the 12S or COI genes, a pragmatic and increasingly recommended approach is to perform both denoising and clustering [14]. This strategy allows researchers to report results at two biological levels: the denoised sequences (ESVs) as a proxy for haplotypes, enabling high-resolution and metaphylogeographic studies, and the clusters (MOTUs) as a proxy for species, facilitating traditional biodiversity assessments and comparisons with older studies. By adopting this dual framework, researchers can maximize the biological information extracted from their eDNA metabarcoding data.

Within environmental DNA (eDNA) bioinformatics pipelines, the selection of genetic markers and primers is a foundational decision that profoundly influences the accuracy, scope, and reliability of biodiversity assessments [19] [20]. The metabarcoding workflow, from sample collection to taxonomic assignment, is susceptible to various biases, among which primer bias is a critical constraint that can skew community composition profiles [19]. This application note provides a critical evaluation of four predominant genetic markers—12S rRNA, COI, 16S rRNA, and ITS—synthesizing recent research to guide their application in eDNA studies targeting fish, vertebrates, fungi, and other eukaryotes. We present structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and a standardized bioinformatic workflow to enhance the reproducibility and robustness of eDNA metabarcoding research.

Marker Performance Comparison and Selection Guidelines

The performance of metabarcoding primers varies significantly based on the target taxonomic group, ecosystem, and specific primer set used. Below, a comparative analysis of key marker genes is provided to inform selection.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Key Metabarcoding Markers

| Marker | Primary Target | Key Primer Sets | Amplicon Length | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12S rRNA | Fish, Vertebrates | MiFish12S, Riaz12S, Valentini_12S [21] | 63-171 bp [21] | High taxonomic resolution for fishes; effective for elusive species like elasmobranchs (e.g., Riaz_12S) [21]; high detection success in vertebrates [22]. | Species detection varies by primer set (e.g., 32 vs. 55 species detected by different 12S primers) [21]. |

| COI | Animals, Metazoans | Leray, COI_Leray [23] | ~313 bp [23] | Extensive reference database (BOLD, NCBI) [24]; standard barcode for animals. | High primer degeneracy can lead to non-target amplification [21]; less commonly used for eDNA metabarcoding due to this issue [21]. |

| 16S rRNA | Prokaryotes, Fish | Berry_16S [21] | 219 bp [21] | Reliable for fish diversity; comparable species detection (49 species) to best 12S primers [21]. | Primarily used for prokaryotes; application in vertebrates is more limited. |

| ITS | Fungi | ITS1, ITS2 [25] | Variable (often 200-600 bp) | Official fungal barcode [25]; high taxonomic resolution. | Inconsistent performance between subregions; ITS1 outperforms ITS2 in richness and resembles shotgun metagenomic profiles more closely [25]. |

Multi-marker approaches are highly recommended to maximize species detection and improve the reliability of results [21] [22]. For instance, employing a combination of the Riaz12S and Berry16S primers detected 93.4% of the total fish species identified in a complex estuarine system, whereas the best-performing single primer set detected only 85.5% [21]. Similarly, using multiple universal primer sets targeting different genes (12S, 16S, COI) can theoretically increase vertebrate species detection success to over 99% [22].

Table 2: Quantitative Detection Rates of Different Primer Sets in Empirical Studies

| Study Context | Primer Set(s) | Target Gene | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estuarine Fish (Indian River Lagoon, Florida) | Riaz_12S | 12S rRNA | Detected 55 species and the highest number of elasmobranchs (6 species) [21]. | [21] |

| Berry_16S | 16S rRNA | Detected 49 species, performance comparable to Riaz_12S [21]. | [21] | |

| MiFish_12S | 12S rRNA | Detected 34 species [21]. | [21] | |

| Valentini_12S | 12S rRNA | Detected 32 species [21]. | [21] | |

| Riaz12S + Berry16S | 12S & 16S | Combined detection of 71 out of 76 total species (93.4%) [21]. | [21] | |

| Fungal Bioaerosols | ITS1 | ITS | Outperformed ITS2 in richness and taxonomic coverage; profile more closely resembled shotgun metagenomic results [25]. | [25] |

| Universal Vertebrate Primers | VertU (V12S-U, V16S-U, VCOI-U) | 12S, 16S, COI | Over 90% species detection success in mock and zoo eDNA tests, outperforming previous primer sets [22]. | [22] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for eDNA Metabarcoding

The following protocol outlines a standardized workflow for water sample collection through to library preparation, adaptable for a multi-marker approach.

Materials and Equipment

- Sterile Sampling Bottles: Nalgene bottles, sterilized with 20% sodium hypochlorite [21].

- Filtration System: Sterilized filter holders and forceps [21].

- Filters: 0.45 μm mixed cellulose ester (MCE) membranes [21].

- Preservation Buffer: Longmire's buffer or similar DNA preservation solution [21].

- PCR Reagents: Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, appropriate buffer with MgCl₂ [24].

- Primer Stocks: Aliquot primer sets (e.g., Riaz12S, Berry16S, ITS1) at 10 μM working concentration [21] [24].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Field Sampling and Filtration:

- Collect water samples (e.g., 500 mL) in sterile bottles from the target environment [21]. Include field negative controls using bottled water processed identically [21].

- Filter water samples onto 0.45 μm MCE filters using sterilized equipment. For turbid waters, pre-filtration or smaller volumes may be necessary [21].

- Using sterile forceps, transfer each filter to a labeled tube containing 3 mL of Longmire's buffer. Store at -20°C until DNA extraction [21].

DNA Extraction:

- Perform DNA extraction in a dedicated, PCR-free workspace to prevent contamination [21].

- Extract genomic DNA from half of each filter membrane using a commercial soil or water DNA extraction kit, following the manufacturer's protocol. Elute DNA in a final volume of 50-100 μL.

- Include a laboratory negative control (extraction blank) during the extraction process.

PCR Amplification and Library Preparation:

- Primer Selection: Select appropriate primer sets based on the target taxa (Refer to Table 1). For comprehensive vertebrate surveys, use a multi-marker approach (e.g., V12S-U, V16S-U, VCOI-U) [22].

- PCR Reaction: Set up reactions in a total volume of 10-25 μL. A sample 10 μL mixture includes [24]:

- 7.0 μL ultrapure water

- 1.0 μL 10X PCR buffer (containing 2.5 mM MgCl₂)

- 0.3 μL dNTP mix (10 mM each)

- 0.25 μL each forward and reverse primer (10 μM)

- 0.2 μL Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL)

- 1.0 μL template DNA

- Thermal Cycling: Conditions must be optimized for each primer set. An example profile for 12S amplification is [24]:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- 35-40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 1 minute.

- Annealing: 57°C (Optimize for specific primer: e.g., 55°C for Riaz12S, 61.5°C for MiFish12S) [21] for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes.

- Library Indexing and Purification: Index each sample with unique dual indices in a subsequent limited-cycle PCR. Clean up the final amplified libraries using magnetic beads.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

Post-sequencing analysis requires a robust and reproducible bioinformatic pipeline to transform raw sequencing data into reliable taxonomic assignments.

Critical Steps and Tool Recommendations

- Read Preprocessing & Denoising: Use tools like SEQPREP for pairing forward and reverse reads [26]. Denoising, which includes the removal of rare clusters, sequences with putative errors, and chimeric sequences, can be performed with DADA2 to generate Exact Sequence Variants (ESVs) for higher resolution than traditional OTUs [26].

- Taxonomic Assignment: This is a critical step influenced by the classifier and reference database.

- Classifier Selection: Benchmarks on marine vertebrates show that MMSeqs2 and Metabuli generally outperform BLAST for 12S and 16S rRNA markers, providing higher F1 scores and being less susceptible to false positives [23]. For COI markers, Naive Bayes Classifiers (NBC) like Mothur can outperform sequence-based classifiers [23].

- Reference Database Curation: The importance of using a custom-curated reference database cannot be overstated. Public databases often contain mislabeled sequences, which compromise identification accuracy [23] [19]. Database curation has been shown to increase species detection rates and reliability [23]. Always use a database tailored to your study region and target taxa.

Integrated Pipeline Solutions

Pipelines like MetaWorks provide a harmonized environment for processing multi-marker metabarcoding data [26]. MetaWorks supports popular markers (12S, 16S, COI, ITS, etc.), incorporates the RDP classifier for taxonomic assignment with confidence measures, and includes marker-specific processing steps like ITS region extraction and pseudogene removal for protein-coding genes [26]. Its use of Snakemake ensures scalability and reproducibility on high-performance computing clusters [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for eDNA Metabarcoding

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Sterile Sampling Bottles | Collection and transport of water samples without cross-contamination. | Sterilized Nalgene bottles [21]. |

| Mixed Cellulose Ester (MCE) Filters | Capturing eDNA particles from water samples. | 0.45 μm pore size [21]. |

| Longmire's Buffer | Preservation of DNA on filters post-filtration, preventing degradation. | Liquid preservation buffer for storage at -20°C [21]. |

| Taxon-Specific Primers | PCR amplification of target barcode regions from eDNA. | MiFish12S (fish), Riaz12S (vertebrates), ITS1 (fungi) [21] [25]. |

| Curated Reference Database | Accurate taxonomic assignment of sequenced ESVs/OTUs. | Custom database of local species; critical for reliability [23] [19]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Processing raw sequencing data into taxonomic assignments. | MetaWorks, QIIME2, DADA2 [26]. |

The selection of genetic markers and corresponding primers is a critical step that directly determines the success of an eDNA metabarcoding study. No single marker is universally optimal; each has strengths and weaknesses for specific taxonomic groups and applications. The current state of the art strongly advocates for a multi-marker approach to maximize species detection and improve the reliability of results [21] [22]. This strategy, coupled with rigorous laboratory protocols, the use of curated reference databases, and robust bioinformatic pipelines like MetaWorks that leverage high-performance classifiers such as MMSeqs2, is essential for generating accurate and reproducible biodiversity data [23] [26]. By adhering to these guidelines and leveraging the provided protocols, researchers can significantly enhance the effectiveness of their eDNA bioinformatics pipelines, ultimately contributing to more confident conservation and management decisions.

The Impact of Pipeline Philosophy on Biological Interpretation of Data

In environmental DNA (eDNA) research, the bioinformatic pipeline is a critical bridge between raw genetic sequences and biological insights. The choice of pipeline, however, extends beyond mere technical preference—it embodies a particular philosophy regarding how sequence data should be processed, clustered, and classified. These philosophical differences manifest in critical design choices: whether to cluster sequences by similarity into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) or to resolve exact biological sequences as amplicon sequence variants (ASVs); whether to use alignment-based, Bayesian, or machine learning approaches for taxonomic assignment; and whether to prioritize computational efficiency over maximum sensitivity [1] [27]. Within the context of eDNA bioinformatics, these philosophical commitments may potentially influence the resulting biodiversity metrics and ecological interpretations. This application note examines how these underlying philosophies impact biological conclusions in eDNA studies, providing researchers with structured comparisons and experimental protocols to inform their analytical choices.

Philosophical Approaches in eDNA Bioinformatics

Bioinformatic pipelines for eDNA analysis incorporate distinct philosophical approaches to data processing, each with implications for biological interpretation.

Clustering Philosophy: OTUs vs. ASVs

The fundamental division in pipeline philosophy concerns the treatment of sequence variants. OTU-based approaches cluster sequences based on a similarity threshold (typically 97%), operating under the philosophical premise that molecular operational units should approximate species-level distinctions while accommodating technical noise. In contrast, ASV-based approaches attempt to resolve exact biological sequences through error modeling, embodying the philosophy that true biological sequences can be distinguished from PCR and sequencing errors without relying on arbitrary clustering thresholds [1]. The Anacapa pipeline exemplifies the ASV philosophy through its implementation of DADA2, while metaBEAT utilizes VSEARCH for OTU creation, representing these divergent approaches [1].

Taxonomic Assignment Philosophy

Pipelines also diverge philosophically in their approach to taxonomic classification:

- Alignment-based methods (Barque, metaBEAT, MiFish) use global or local alignment against reference databases, prioritizing sequence similarity as the primary criterion for taxonomic placement [1].

- Bayesian methods (Anacapa's BLCA implementation) utilize Bayesian lowest common ancestor algorithms that incorporate probabilistic reasoning about taxonomic placement without requiring a training step [1].

- Machine learning approaches (SEQme's use of RDP classifier) employ trained models to classify sequences, emphasizing pattern recognition over direct sequence alignment [1].

Comparative Analysis of Pipeline Performance

Empirical Comparison of Taxonomic Detection

A systematic comparison of five bioinformatic pipelines (Anacapa, Barque, metaBEAT, MiFish, and SEQme) using eDNA samples from Czech reservoirs revealed both consistency and divergence in taxonomic detection.

Table 1: Comparison of Five Bioinformatics Pipelines for eDNA Metabarcoding

| Pipeline | Clustering Method | Taxonomic Assignment | Key Characteristics | Species Detection Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacapa | ASV (DADA2) | Bayesian (BLCA) | Distinguishes biological sequences from errors; no training step required | High sensitivity for true variants |

| Barque | No clustering | Alignment-based (VSEARCH) | Read annotation only; global alignment | Dependent on reference database quality |

| metaBEAT | OTU (VSEARCH) | Alignment-based (BLAST) | Local alignment for taxonomy; similar tools to Barque | Balanced sensitivity/specificity |

| MiFish | Custom | Alignment-based (BLAST) | Protocol-specific tools; BLAST classification | Optimized for 12S rRNA targets |

| SEQme | Custom | Machine Learning (RDP) | Sequence merging before trimming; Bayesian classifier | Pattern recognition approach |

Despite their philosophical differences, the study found consistent taxa detection across pipelines, with increased sensitivity compared to traditional survey methods [1]. Statistical analyses of alpha and beta diversity measures showed significant similarities between pipelines, suggesting that core ecological patterns remain robust to pipeline philosophy [1]. The Mantel test further confirmed these relationships, indicating that overall community composition patterns were preserved across analytical approaches.

Impact on Ecological Interpretation

The Czech reservoir study demonstrated that the choice of bioinformatic pipeline did not significantly alter the primary ecological conclusions regarding seasonal patterns and reservoir differences [1]. However, finer-scale analysis revealed that divergences became more pronounced when examining specific interactions between reservoir location, seasonal timing, and their combined effects [1]. This suggests that while broad ecological patterns are robust to pipeline choice, more nuanced environmental interpretations may be philosophy-dependent.

Experimental Protocol for Pipeline Comparison

Sample Collection and Processing

Materials:

- Sampling Equipment: Sterile water collection bottles, filters (0.22-1.0 μm pore size), filtration apparatus

- Preservation Solution: Longmire's buffer or ethanol for sample preservation

- Extraction Kit: Commercial DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerWater Kit)

- PCR Reagents: Primers targeting appropriate barcode region (e.g., 12S rRNA for fish), high-fidelity polymerase, dNTPs

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina, Ion Torrent, or other NGS platform

Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect water samples from predetermined sites, ensuring appropriate spatial and temporal replication for the ecological question.

- Filtration: Filter 1-2 liters of water through sterile membranes using aseptic technique to capture eDNA.

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from filters following manufacturer protocols, including negative controls to monitor contamination.

- Library Preparation: Amplify target region (e.g., 12S rRNA) using metabarcoding primers with attached adapters. Include positive controls (known species DNA) and negative (no-template) PCR controls.

- Sequencing: Sequence amplified libraries on appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) with sufficient depth (>100,000 reads per sample).

Multi-Pipeline Analysis Workflow

Computational Requirements:

- Computing Resources: High-performance computing cluster or workstation with sufficient RAM (≥32GB) and multi-core processors

- Containerization: Docker or Singularity for pipeline implementation

- Reference Databases: Curated taxonomic databases (e.g., MIDORI, SILVA, custom local databases)

Protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Demultiplex sequences by sample and remove primers using cutadapt or similar tools.

- Parallel Processing: Implement each bioinformatic pipeline (Anacapa, Barque, metaBEAT, MiFish, SEQme) using identical input files and parameter settings where applicable.

- Output Standardization: Convert all pipeline outputs to standardized format (e.g., BIOM table) for comparative analysis.

- Statistical Comparison: Calculate alpha diversity (Shannon, Simpson indices), beta diversity (Bray-Curtis, Jaccard distances), and perform Mantel tests between resulting community matrices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for eDNA Pipeline Analysis

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab | Filtration Apparatus | Capturing eDNA from water samples | Pore size (0.22-1.0 μm) affects DNA recovery |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolating high-quality eDNA | Compatibility with filter type; inhibitor removal | |

| Metabarcoding Primers | Amplifying target genes | Taxonomic coverage; amplification bias | |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Reducing PCR errors | Critical for ASV-based approaches | |

| Bioinformatics | Reference Databases | Taxonomic assignment | Coverage and curation impact assignment accuracy |

| Containerization Tools | Reproducible pipeline execution | Docker/Singularity for environment consistency | |

| Quality Control Tools | Assessing sequence data quality | FastQC for initial quality assessment | |

| Statistical Software | Ecological analysis | R with phyloseq, vegan packages |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The philosophical differences embedded in bioinformatic pipelines represent varied approaches to managing the inherent uncertainties in eDNA analysis. While empirical evidence suggests that broad ecological conclusions remain stable across pipeline choices [1], researchers should select pipelines whose underlying philosophy aligns with their specific research questions. For studies requiring fine taxonomic resolution or tracking of specific strains, ASV-based approaches (e.g., Anacapa) may be preferable. For broader ecological surveys or when working with limited reference databases, OTU-based or alignment-based methods may offer practical advantages.

Future developments in eDNA bioinformatics should focus on integrating multiple approaches rather than treating them as mutually exclusive alternatives. Combined use of multiple primer pairs targeting different gene markers and leveraging both local and public databases can improve the sensitivity and reliability of fish eDNA analyses [20]. Furthermore, the emerging field of airborne eDNA and shotgun sequencing approaches presents new challenges and opportunities for pipeline development [28] [29], potentially requiring novel philosophical approaches to data analysis that can handle the complexity of pan-domain-of-life detection without targeted amplification.

The consistency of ecological interpretation across pipeline philosophies provides confidence in the robustness of eDNA metabarcoding as a biomonitoring tool. By understanding the philosophical underpinnings, practical implementations, and empirical performance of different pipelines, researchers can make informed decisions that strengthen the validity and impact of their biological conclusions.

From Code to Discovery: Implementing Pipelines for Biomedical and Ecological Applications

Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive tool for biodiversity monitoring, enabling the characterization of biological communities from various environmental samples such as water, soil, and air [2] [30]. This approach detects traces of genetic material shed by organisms into their environment, bypassing the need for direct observation or physical collection which can be costly, taxonomically biased, and logistically challenging [2]. The field of eDNA research generates vast amounts of sequencing data, creating a critical bottleneck in bioinformatic processing and analysis. The complexity of analyzing millions of sequences demands robust, reproducible, and standardized computational approaches [7] [31].

Automated end-to-end bioinformatic pipelines have been developed to address these challenges, providing integrated solutions that process raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful results. These pipelines streamline the computationally intensive steps of demultiplexing, quality filtering, sequence variant deduction, taxonomic assignment, and data visualization within a unified framework [7] [32]. This article examines three prominent automated pipelines—REVAMP, Anacapa, and PacMAN—detailing their workflows, applications, and experimental protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing these tools for eDNA metabarcoding studies. Their development represents a significant step toward operationalizing eDNA approaches for large-scale biodiversity monitoring and conservation efforts [7].

Comparative Analysis of Pipeline Architectures

The three pipelines, while sharing the common goal of streamlining eDNA analysis, are architecturally and functionally distinct, each designed with specific applications and user communities in mind. REVAMP (Rapid Exploration and Visualization through an Automated Metabarcoding Pipeline) is designed for rapid data exploration and visualization, generating hundreds of figures to facilitate hypothesis generation [7]. The Anacapa Toolkit provides a modular solution for processing multilocus metabarcode datasets with high precision, employing a Bayesian method for taxonomic assignment [33] [32]. In contrast, the PacMAN (Pacific Islands Marine Bioinvasions Alert Network) pipeline is a specialized, action-oriented framework focused on the early detection of marine invasive species and features an operational dashboard for decision-makers [34].

Table 1: Core Functional Comparison of REVAMP, Anacapa, and PacMAN

| Feature | REVAMP | Anacapa Toolkit | PacMAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Rapid data exploration & visualization [7] | High-precision taxonomy assignment [33] | Early detection of marine invasive species [34] |

| Key Input | Raw FASTQ files [7] | Raw FASTQ files [33] | Processed eDNA observations & WRiMS data [34] |

| ASV Deduction | DADA2 [7] | DADA2 [33] | Information not specified |

| Taxonomy Assignment | BLASTn against NCBI nt or SILVAngs [7] | Bayesian LCA algorithm [33] | Integrated with OBIS & WRiMS [34] |

| Key Output | 985+ figures for ecological patterns [7] | ASV tables & taxonomy assignments [33] | Risk assessments & pest status in a dashboard [34] |

| Unique Strength | Extensive automated visualization | Customizable reference databases with CRUX [33] | Decision-support tool for environmental managers [34] |

Table 2: Technical and Performance Specifications

| Specification | REVAMP | Anacapa Toolkit | PacMAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Database | NCBI nt, SILVA [7] | GenBank (via CRUX) [33] | OBIS, WRiMS [34] |

| Reported Runtime | ~3.5 hours for 84 samples (6 processors) [7] | Information not specified | Information not specified |

| Containerization | Not specified | Available via Singularity [33] | Not specified |

| Data Integration | Oceanographic contextual data [7] | Multi-locus marker support [32] | WRiMS distribution & thermal niche data [34] |

A critical consideration for any bioinformatic pipeline is its performance in deducing biological sequences from raw data. REVAMP and Anacapa both utilize the DADA2 algorithm to resolve Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), which provides single-nucleotide resolution and is considered superior to older Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) clustering methods in sensitivity and accuracy [7] [2] [31]. Comparative studies on fish eDNA metabarcoding have demonstrated that denoising algorithms like DADA2 effectively reduce sequencing errors and provide more biologically realistic data, though they may sometimes lead to a reduction in the number of detected taxa compared to OTU-based methods [2].

Workflow Diagrams and Logical Processes

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical workflows for the REVAMP, Anacapa, and PacMAN pipelines, providing a visual guide to their architecture and key decision points.

Diagram 1: REVAMP Workflow. The pipeline processes raw sequences through quality control, denoising, and taxonomic assignment before generating extensive visualizations for ecological analysis [7].

Diagram 2: Anacapa Toolkit Workflow. This modular workflow begins with the optional creation of a custom reference database, processes sequences to ASVs, and uses a Bayesian classifier for taxonomy, culminating in an R-based exploration tool [33] [32].

Diagram 3: PacMAN Operational Framework. This action-oriented framework integrates molecular data with global biodiversity databases to feed a dashboard that supports timely decision-making for marine biosecurity [34].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Implementing the REVAMP Pipeline

The REVAMP pipeline is implemented through a series of defined steps, from raw data processing to visualization. The following protocol is adapted from its application on an EcoFOCI dataset from Alaska and the Arctic, which consisted of 84 samples sequenced for two markers (16S and 18S) [7].

Step 1: Sequence Preprocessing and ASV Inference.

- Input: Raw paired-end sequencing files in FASTQ format.

- Demultiplexing: Use Cutadapt to remove primers and index sequences, assigning reads to their respective samples [7].

- Quality Filtering and Denoising: Process demultiplexed reads through the DADA2 algorithm to correct sequencing errors, merge paired-end reads, remove chimeric sequences, and infer biological Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). This step transforms the raw sequence data into a table of ASVs by sample [7].

Step 2: Taxonomic Assignment.

- Assign taxonomy to each ASV by performing a BLASTn search against the NCBI nucleotide (nt) database and determining the consensus taxonomy of the best hits. Alternatively, for microbial communities, REVAMP can integrate output from the SILVAngs pipeline, which uses a curated taxonomy [7].

Step 3: Data Exploration and Visualization.

- Execute the REVAMP visualization module, which automatically generates a suite of figures (e.g., KRONA plots, alpha and beta diversity analyses) using packages like phyloseq and vegan. This facilitates rapid exploration of ecological patterns and hypothesis generation [7].

Implementing the Anacapa Toolkit

The Anacapa Toolkit employs a modular approach, with its uniqueness lying in the construction of custom reference databases. The protocol below outlines its core steps [33] [32].

Step 1: Reference Database Construction with CRUX.

- Purpose: To create a comprehensive and customized reference database for specific metabarcode markers.

- Process: The CRUX module uses ecoPCR and iterative BLAST searches to extract and curate relevant sequences from GenBank based on the user-specified primer pairs. This ensures the reference database is tailored to the specific genetic marker used in the study [33].

Step 2: Sequence Processing and Classification.

- Quality Control and ASV Inference: The "Anacapa QC and dada2" module demultiplexes raw reads and processes them through DADA2 to generate ASVs [33].

- Taxonomic Assignment: The "Anacapa classifier" module uses Bowtie2 to map ASVs to the custom database built in Step 1. It then employs a modified Bayesian Least Common Ancestor (BLCA) algorithm to assign taxonomy, providing a confidence score for each taxonomic level from kingdom to species [33] [32].

Step 3: Data Analysis with ranacapa.

- Analyze the results using the ranacapa R package and Shiny web app. This tool allows for easy upload of ASV and taxonomy tables, along with sample metadata, to perform preliminary analyses and visualizations, making it accessible for educational and non-specialist use [33].

Deployment of the PacMAN Framework

The PacMAN framework is distinct in its integration of bioinformatics with a decision-support system for environmental management [34].

Step 1: Field and Laboratory Work.

- Collect eDNA samples from the marine environment (e.g., seawater).

- Extract eDNA and perform targeted metabarcoding for relevant species, followed by high-throughput sequencing.

Step 2: Bioinformatics Analysis.

- Process the raw sequence data through the PacMAN bioinformatics pipeline (hosted on GitHub) to identify species present in the samples [35].

Step 3: Data Integration and Risk Assessment.

- Integrate the species detection data with the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS) to access global distribution records.

- Cross-reference detected species with the World Register of Introduced Marine Species (WRiMS) to identify known invasive species and assess their introduction pathways and impacts [34].

Step 4: Dashboard Visualization and Action.

- Input results into the PacMAN operational dashboard. The dashboard provides an intuitive interface for environmental managers to:

- Review and validate species detections.

- Modify the pest status of species in specific areas.

- Access synthesized risk assessments based on distribution and thermal niche data.

- Make informed decisions for mitigation and management actions [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of eDNA experiments relies on a foundation of carefully selected laboratory and computational reagents. The following table details key materials and their functions, as implied by the protocols of the featured pipelines.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for eDNA Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Through Sequencing Platform | Generates raw sequence data (e.g., Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq) [33]. |

| Metabarcode Primers | Target specific gene regions for PCR amplification (e.g., 12S for vertebrates, 16S for microbes, 18S for metazoans) [7] [30]. |

| Reference Database | Curated collection of DNA sequences with verified taxonomy for assigning identities to unknown ASVs (e.g., NCBI nt, SILVA, BOLD, custom CRUX DB) [33] [7] [31]. |

| Bioinformatic Software Dependencies | Underlying tools for specific tasks (e.g., Cutadapt for demultiplexing, DADA2 for denoising, BLASTn for sequence similarity, Bowtie2 for sequence alignment) [33] [7]. |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-performance computing cluster or server with sufficient memory (e.g., 55 GB for REVAMP) and processors for timely data processing [7]. |

The development of automated, end-to-end bioinformatic pipelines like REVAMP, Anacapa, and PacMAN is critical for standardizing and scaling eDNA metabarcoding into a robust tool for biodiversity science and conservation. REVAMP excels in rapid, automated ecological visualization, the Anacapa Toolkit provides high-precision, customizable taxonomy across multiple loci, and PacMAN translates detections into actionable insights for biosecurity. The choice of pipeline depends heavily on the study's objectives: exploratory biodiversity assessment, taxonomically precise community profiling, or targeted monitoring for resource management. As these tools continue to evolve, their integration with growing reference databases and user-friendly interfaces will further empower researchers and managers to harness the full potential of eDNA for understanding and protecting global ecosystems.

The Ocean Biomolecular Observing Network (OBON) is a global programme championing biomolecular techniques like environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis to revolutionize ocean biodiversity monitoring [36]. This initiative leverages the universal presence of biomolecular traces—such as DNA, RNA, and proteins—shed by all marine organisms into their environment. The core vision is to accelerate informed decision-making to restore ocean health by creating a centralized hub for the biomolecular measurement of marine life [36]. Operationalizing these technologies is critical for understanding and predicting ecosystem changes in response to climate change and anthropogenic pressures, thereby supporting sustainable fisheries management and overall ocean stewardship [37].

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is at the forefront of integrating these 'Omics tools into its core mission. NOAA's strategy focuses on developing technology to improve science and stewardship, transitioning results for societal benefit, and providing the foundational biodiversity information necessary for climate-resilient ecosystem-based fisheries management [37]. This involves a concerted effort to move from proof-of-concept studies to robust, operational workflows that can be routinely deployed on observatories and research vessels to deliver reliable, actionable data.

Strategic Framework and Core Objectives

The strategic framework for operationalizing ocean biomolecular observatories is built upon a set of clearly defined, interconnected objectives designed to ensure comprehensive and sustainable implementation.

Objective 1: Build a Multi-Omics Biodiversity Observing System – This objective focuses on establishing a coordinated global network for biomolecular data collection. It involves developing capabilities for the collection, analysis, and archival of biomolecules from both fixed locations (e.g., time-series stations like the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS) and the Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT)) and autonomous platforms [36]. The long-term goal is to deploy a global network of autonomous platforms with biomolecular sensing capability, analogous to the Argo network for physical ocean measurements, to achieve persistent synoptic observations of ocean biology [36].

Objective 2: Develop and Transfer Capacity – A key pillar of the strategy is to ensure global equity in biomolecular observation capabilities. This involves initiating additional marine biomolecular observation activities through targeted training programs coupled with funded equipment programs [36]. These programs, developed in collaboration with involved nations, will focus on addressing issues outlined in the UN Ocean Decade goals and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as predicting biological hazards and managing protected ecosystems [36].

Objective 3: Enhance Marine Ecosystem Models – This objective aims to bridge the gap between raw data and predictive understanding by integrating biomolecular components into marine ecosystem models. The models will utilize data from coordinated molecular observations to generate 4D multi-omic biodiversity seascapes [36]. The strategy emphasizes supporting basic open-source modeling efforts and ensuring that data flows are standardized and harmonized (FAIR principles) to secure a robust digital legacy [36].

Objective 4: Address Pressing Scientific and Management Questions – The final objective ensures that the observing system is developed in partnership with end-users and stakeholders. The programme is designed from the outset to provide solutions for scientific, management, and policy challenges related to the state and dynamics of marine life, including exploited resources [36]. This user-centric approach is essential for communicating the system's importance and ensuring its utility for sustainable development.

Table 1: Key Challenges and Strategic Solutions in Operationalizing eDNA for Stock Assessments [38]

| Challenge | Strategic Solution |

|---|---|

| Linking eDNA signal to species abundance | Improve quantitative understanding of eDNA shedding and decay rates; develop mechanistic frameworks. |

| Reducing detection errors (false positives/negatives) | Establish and adhere to widely accepted best practices for experiment design and data analysis. |

| Understanding eDNA spatial and temporal dynamics | Conduct targeted studies on eDNA fate and transport; integrate with hydrodynamic models. |

| Acquiring biological data (age, weight, etc.) | Pair eDNA surveys with traditional methods (trawl surveys, fishery observers) for complementary data. |

| Measuring and accounting for uncertainty | Conduct rigorous evaluations to quantify sources of error in eDNA-based estimates. |

| Overcoming skepticism towards new methods | Foster interdisciplinary collaboration; demonstrate reliability through intercalibration and validation. |

Application Notes: Protocols for Ocean Biomolecular Observation

Sample Collection and Processing Workflow