Ecogenomics: HUGO CELS's Vision for a One Health Approach in Genomics and Drug Development

This article explores the transformative perspective of the HUGO Committee on Ethics, Law, and Society (CELS) on Ecogenomics—an interdisciplinary field that integrates genomic sciences with ecological and environmental research through...

Ecogenomics: HUGO CELS's Vision for a One Health Approach in Genomics and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative perspective of the HUGO Committee on Ethics, Law, and Society (CELS) on Ecogenomics—an interdisciplinary field that integrates genomic sciences with ecological and environmental research through a One Health lens. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we detail the foundational principles of the proposed 'Ecological Genome Project,' its methodological applications in multi-omics and AI, the challenges in data integration and ethical governance, and its validation through frameworks like benefit-sharing and biodiversity targets. The synthesis provides a roadmap for embedding ecological and ethical considerations into the future of biomedical research and therapeutic development.

What is Ecogenomics? Exploring HUGO's Vision for Genomic and Environmental Integration

Ecogenomics represents a paradigm shift in genomic sciences, emerging as an integrated, unifying approach to study genomes within their broader social and natural environments. The Human Genome Organisation (HUGO), through its Committee on Ethics, Law and Society (CELS), has championed this expanded vision that connects human genomics to ecological systems. This perspective moves beyond anthropocentric views to recognize that human health and genomic expression are intrinsically linked to the health of ecosystems and the planetary biosphere [1]. The field has evolved from earlier concepts of human ecology and ecogenetics, which initially focused on human responses to environmental contaminants, into a comprehensive framework that acknowledges the reciprocal interactions between human genomes and the complex ecological networks we inhabit [1].

This conceptual expansion aligns with global environmental frameworks, particularly the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted at COP15, which emphasizes the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity [1]. HUGO CELS has identified this international policy shift as significant for genomic sciences, advocating for Ecogenomics as a blueprint to address the interconnected environmental challenges facing modern societies, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation [1]. The Ecological Genome Project emerges as an aspirational global initiative within this framework, inspired by the ambitious scale of The Human Genome Project, aiming to explore the profound connections between human well-being and the diversity of non-human species that sustain planetary health [1].

Defining the Ecogenomics Framework: Core Principles and Scope

Conceptual Foundations and Definition

Ecogenomics constitutes the conceptual study of genomes within their social and natural environments, investigating how environmental factors influence an organism's genome through ambient conditions in the biosphere and direct contact with chemical, physical, and biological agents [1]. The field recognizes three interconnected domains of inquiry: (1) the application of genomic approaches to develop biotechnological solutions for sustainable development goals; (2) the study of how human genomes are embedded within and influenced by ecosystems; and (3) the understanding of environments as dynamic spaces connecting humans with other biotic communities through shared natural histories and genomic similarities [1].

This framework operates on the core principle that human life on Earth fundamentally relies on the diversity of other species, creating dependencies and interactions that Ecogenomics seeks to understand through integrated multi-omics approaches [1]. The field expands human ecology into a grand vision of our planetary "home" (from the Greek oikos), connecting molecular and exposome studies of human and non-human life within shared environments and communities [1]. These relationships affect organisms throughout their lifetimes and can produce heritable changes that shape evolutionary trajectories across species boundaries.

HUGO's Vision and the One Health Approach

HUGO CELS formally recommends adopting an interdisciplinary One Health approach in genomic sciences to promote ethical environmentalism [1]. The One Health framework is defined by the World Health Organization as "an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems" [1]. This approach recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent [1].

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework explicitly calls for a One Health Approach, affirming the "rights of nature and rights of Mother Earth" as integral to its successful implementation [1]. Within this context, HUGO's vision involves supporting multiple intellectual trajectories to achieve global biodiversity targets through promoting public good, advocating for benefit sharing, and exploring global governance mechanisms for genomic resources [1]. This represents a significant evolution from HUGO's initial focus on human genomics to encompass environmental research and ecological conservation, reflecting a growing recognition that genomic sciences must address the interconnected crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation [2].

Table: The Three Core Domains of Ecogenomics According to HUGO CELS

| Domain | Focus Area | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Biotechnological Development | Using genomics to develop solutions from ecosystem services | Gene-edited crops; Modified compounds for SDGs; Benefit-sharing frameworks |

| Environmental Genomic Influence | Studying how genomes are embedded in ecosystems | Molecular study of environmental influences; Heritable variations; Personal microbiome changes |

| Dynamic Environmental Connections | Understanding interdependent relationships with nature | Ethical, legal, and social investigation of species relationships; Comparative genomic diversity |

Methodological Approaches in Ecogenomics Research

Experimental Workflows and Technical Protocols

Ecogenomics research employs sophisticated methodological approaches that integrate field sampling, molecular analysis, and computational techniques. The experimental workflow typically begins with comprehensive environmental sampling across stratified ecosystems to capture biological gradients and ecological niches. For example, in marine systems like the Yongle Blue Hole (YBH), researchers collect water samples across oxic, chemocline, and anoxic zones using Niskin bottles, followed by sequential filtration to separate cellular fractions (>0.22μm) from viral fractions (<0.22μm) [3]. This fractionation enables specialized analysis of different biological components within the same ecosystem.

For terrestrial ecosystems, the Microflora Danica project exemplifies large-scale environmental genomic sampling, utilizing deep long-read Nanopore sequencing of 154 soil and sediment samples (median ~95 Gbp per sample) to recover microbial genomes from highly complex environmental matrices [4]. The project developed the mmlong2 bioinformatics workflow, which incorporates multiple optimizations for recovering prokaryotic metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from extremely complex datasets through metagenome assembly, polishing, eukaryotic contig removal, and extraction of circular MAGs as separate genome bins [4]. This workflow employs differential coverage binning (incorporating read mapping information from multi-sample datasets), ensemble binning (using multiple binners on the same metagenome), and iterative binning (repeated binning of the metagenome) to maximize MAG recovery from high-complexity samples [4].

Table: Key Methodological Approaches in Ecogenomics Studies

| Methodology | Technical Specifications | Applications in Ecogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic Sequencing | Deep long-read Nanopore sequencing (~100 Gbp/sample); SPAdes assembly with multiple k-mer sizes | Recovery of microbial genomes from complex soils and sediments; Viral community characterization |

| Fractionation Techniques | Sequential filtration (0.22μm membranes); Iron chloride flocculation for viral concentration | Separation of cellular and viral fractions; Analysis of host-virus interactions in environments |

| Bioinformatics Workflows | mmlong2 pipeline; VirSorter2, VIBRANT, DeepVirFinder for viral identification; CheckV for quality assessment | MAG recovery from complex samples; Viral contig identification; Genome quality evaluation |

| Community Analysis | vOTU clustering at species level (CD-HIT, 95% identity, 85% coverage); Taxonomic assignment with Prodigal | Viral diversity assessment; Comparative analysis across redox gradients; Functional potential evaluation |

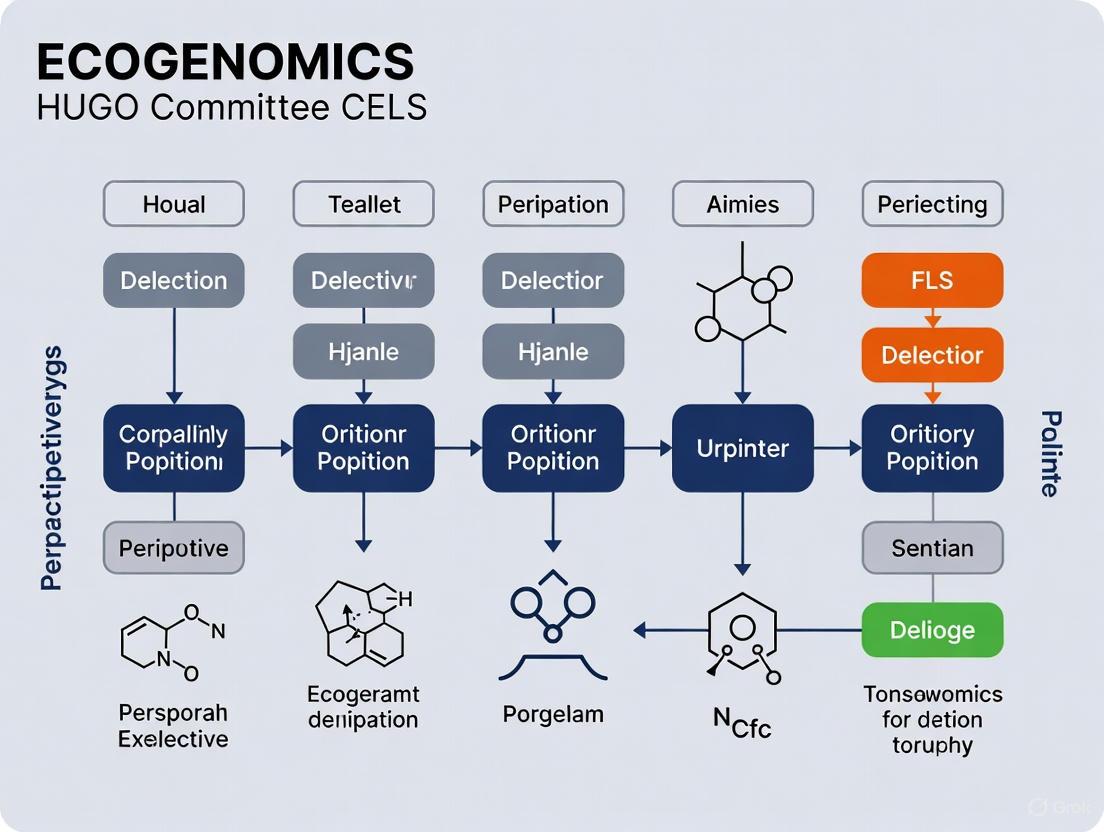

Visualization of Ecogenomics Research Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for ecogenomics research, particularly in stratified aquatic ecosystems like the Yongle Blue Hole:

Ecogenomics Research Workflow: Integrated experimental and computational pipeline for studying complex ecosystems.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ecogenomics Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ecogenomics Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Ecogenomics Research |

|---|---|---|

| Polycarbonate Membranes | 142-mm diameter, 0.22-µm pore size (Millipore) | Collection of microbial cells and planktonic viruses from water samples |

| DNA Extraction Kits | FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals) | High-yield DNA extraction from complex environmental matrices |

| Library Preparation Kits | VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina V3 (Vazyme) | Metagenomic library construction for high-throughput sequencing |

| Concentration Devices | 100 kDa Amicon centrifugal devices | Concentration of viral particles from filtered water samples |

| Resuspension Buffer | Ascorbic-EDTA buffer (0.1 M EDTA, 0.2 M MgCl₂, 0.2 M ascorbic acid, pH 6.0) | Preservation and resuspension of concentrated viral particles |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina Novaseq 6000 (2×150 bp); Nanopore sequencing | Generation of metagenomic data from environmental samples |

Key Research Findings and Ecological Insights

Viral Ecogenomics in Stratified Marine Ecosystems

Research in the Yongle Blue Hole (YBH) has revealed remarkable viral diversity and niche separation across oxygen gradients. Metagenomic analysis identified 1,730 viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs), with over 70% affiliated with Caudoviricetes and Megaviricetes classes, particularly within Kyanoviridae, Phycodnaviridae, and Mimiviridae families [3]. The study demonstrated significant stratification in viral communities, with deeper anoxic layers containing a high proportion of novel viral genera, while oxic layer viral genera overlapped with those found in open waters of the South China Sea [3].

Functional analysis revealed that YBH viruses encode diverse auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) that may influence photosynthetic and chemosynthetic pathways, as well as methane, nitrogen, and sulfur metabolisms [3]. Several high-abundance AMGs appeared potentially involved in prokaryotic assimilatory sulfur reduction, suggesting viruses play crucial roles in biogeochemical cycling within this enclosed ecosystem [3]. Virus-linked prokaryotic hosts predominantly belonged to Patescibacteria, Desulfobacterota, and Planctomycetota phyla, indicating specific virus-host interactions across the redox gradient [3].

Terrestrial Microbial Diversity Expansion Through Long-Read Sequencing

The Microflora Danica project demonstrated the power of long-read sequencing for expanding known microbial diversity in terrestrial habitats. Through deep Nanopore sequencing of 154 soil and sediment samples, researchers recovered 15,314 previously undescribed microbial species, spanning 1,086 previously uncharacterized genera and expanding the phylogenetic diversity of the prokaryotic tree of life by 8% [4]. The mmlong2 workflow enabled recovery of 6,076 high-quality and 17,767 medium-quality MAGs from these highly complex environmental samples [4].

The study revealed substantial variation in MAG recovery across different habitat types, with coastal habitats yielding the highest MAG recovery metrics, while agricultural field samples showed relatively poor yields despite comparable sequencing efforts [4]. This variation was attributed to ecological differences between habitats, including differences in microbial community composition, microdiversity, and the presence of dominant species [4]. The incorporation of these recovered genomes into public genomic databases substantially improved species-level classification rates for soil and sediment metagenomic datasets, highlighting the value of expanding reference databases for ecological studies [4].

Visualization of Ecological Gradients and Microbial Community Structure

The following diagram illustrates the stratified ecosystem of the Yongle Blue Hole and the distribution of viral communities across redox gradients:

Stratified Ecosystem and Viral Distribution: Microbial and viral community structure across redox gradients in the Yongle Blue Hole.

HUGO's Strategic Implementation and Future Directions

Ethical Framework and Global Governance

HUGO CELS has established a comprehensive ethical framework for Ecogenomics that emphasizes benefit sharing, genomic solidarity, and ethical environmentalism. This framework builds upon HUGO's pioneering 2000 statement recommending that "all humanity share in, and have access to, the benefits of genomic research" [1]. The 2019 reaffirmation by HUGO CELS established solidarity as a prerequisite for an ethical open commons in which data and resources are shared, emphasizing that reducing health inequalities among populations requires promoting egalitarian access to the benefits of scientific progress [1].

In response to evolving global challenges, HUGO is coordinating workshops to re-examine the ethics and law of data sovereignty in the context of common human heritage and population-specific genomic variation [2]. This includes developing new statements that reflect contemporary ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of genomic research, moving beyond historical frameworks to address issues of community engagement, indigenous data sovereignty, and equitable participation in genomic sciences [1] [2]. These efforts align with the World Health Organization's recent guidance for human genome data collection, access, use, and sharing, which aims to "promote the use of common principles in laws, policies, frameworks and guidelines, within and across countries and contexts" [2].

Implementation Initiatives and Capacity Building

HUGO's Education Committee has undertaken significant capacity-building initiatives to support the global implementation of genomic sciences. In 2024, the committee maintained strong direct links to international genomics education committees through its geographically widespread international members [2]. The committee's web pages have received visits from over 100 countries worldwide, demonstrating global engagement with genomic education resources [2].

Specific initiatives include the Genetic Counselling Subcommittee's completion of a Delphi study to identify essential educational components for genetic counsellor training programs in regions where the profession is non-existent or in early development stages [2]. The HUGO Variants in Journals committee has advanced efforts to improve diagnostic rates by standardizing variant naming in literature through implementation of VariantValidator [2]. Additionally, the South Asia Genomic Healthcare Alliance, initiated by the Genomic Medicine Foundation UK in collaboration with academic institutions and healthcare providers across South Asia, has established genomic education as central to its objectives [2].

Table: HUGO's Strategic Priorities for Ecogenomics Implementation

| Strategic Area | Current Initiatives | Future Directions |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical Framework | Revisiting benefit sharing statements; Workshops on data sovereignty | Developing new ELSI statements; Aligning with WHO governance frameworks |

| Education & Capacity Building | Genetic counselling training; Global genomic education initiatives | Expanding educational resources for LMICs; Developing international consensus curricula |

| Research Expansion | Ecogenomics Socratic workshops; Conference sessions on environmental genomics | Including ecological sessions at genome meetings; Promoting interdisciplinary collaboration |

| Technical Standards | HGVS nomenclature updates; ISCN 2024 guidelines; VariantValidator implementation | Enhancing machine readability; Maintaining stability for clinical applications |

The vision for Ecogenomics articulated by HUGO CELS represents a transformative expansion of genomic sciences beyond anthropocentric perspectives to embrace the complex interconnections between human genomes and the ecological systems we inhabit. This paradigm recognizes that social determinants of health, environmental conditions, and genetic factors work synergistically to influence risk profiles for complex illnesses across human populations and ecosystems alike [1]. The proposed Ecological Genome Project emerges as an aspirational framework for exploring these connections through interdisciplinary engagement between genomics, ecology, and conservation practice [1].

The methodological advances in environmental genomics, demonstrated through studies of stratified aquatic ecosystems and terrestrial microbial diversity, provide powerful tools for cataloging planetary biodiversity and understanding the functional interactions that sustain ecosystem health [3] [4]. HUGO's ethical framework of benefit sharing, genomic solidarity, and responsible governance offers principles for ensuring these scientific advances translate to equitable benefits for both human communities and the ecological systems on which we depend [1] [2]. As genetic testing becomes increasingly important in healthcare and research, the integration of ecological perspectives through Ecogenomics will be essential for developing sustainable approaches to managing the health of people, animals, and the planetary biosphere as an interconnected whole.

The Role of the HUGO Committee on Ethics, Law, and Society (CELS)

The Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) was established in 1988 as an international coordinating scientific body to promote genomic research and bring its benefits to humanity worldwide [5] [6]. Within this framework, the HUGO Committee on Ethics, Law and Society (CELS) serves as a proactive interdisciplinary working group tasked with analyzing bioethical matters in genomics at a conceptual level with an international perspective [7] [5]. Originally formed as the HUGO Ethics Committee in 1992 under the leadership of Nancy Wexler, the committee was reconstituted as CELS in 2010 to broaden its scope [5]. CELS functions as a unique bioethical interface between scientific and medical communities, identifying opportunities for cultural change within scientific communities whose aspirations align with the public good [7].

CELS has established itself as a thought leader through scholarly engagement, thought-provoking papers, and policy-guiding statements [5]. The committee's mission encompasses several key objectives: leading discussion of ethical, legal, and social issues relating to genomic knowledge; collaborating with international bodies to establish standards; providing ELSI advice to the HUGO Board; and disseminating research through academic publications and formal statements [7]. Under the current leadership of Chair Benjamin Capps, CELS has increasingly focused on emerging challenges including ecological genomics, data sovereignty, and the ethical implications of gene editing technologies [7] [2] [8].

Table: Historical Development of HUGO CELS

| Year | Key Milestone | Leadership | Major Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | First HUGO Ethics Committee meeting | Nancy Wexler (Chair) | Establishment of foundational ethical principles |

| 1996-2008 | Expansion of ethical guidelines | Bartha Knoppers (Chair) | Multiple statements on DNA sampling, benefit sharing, and cloning |

| 2010 | Reconstitution as CELS | Ruth Chadwick (Chair) | Broader mandate encompassing law and society |

| 2017-present | Focus on emerging technologies | Benjamin Capps (Chair) | Ecogenomics, gene editing ethics, data sovereignty |

The Conceptual Framework of Ecogenomics: A CELS Perspective

Defining Ecogenomics and its Principles

The CELS perspective on Ecogenomics represents a significant expansion of HUGO's mandate to include ecological genomics, positioning it as a conceptual study of genomes within their social and natural environments [1]. This framework emerged from the recognition that the environment influences an organism's genome through ambient factors in the biosphere, epigenetic effects of chemicals and pollution, and interactions with pathogenic organisms [1]. Ecogenomics, as articulated by CELS, moves beyond anthropocentric outcome measures to explore reciprocal interactions between genomic theory and empirical observations from fields, laboratories, and clinics [2].

CELS defines Ecogenomics through three interconnected areas of concern. First, it examines how genomics develops biotechnological opportunities from ecosystem services to achieve Sustainable Development Goals, particularly emphasizing the Nagoya Protocol's principle of fair and equitable benefit-sharing from genetic resources [1]. Second, it recognizes how the human genome is embedded within ecosystems and influenced by diverse environmental factors, representing the molecular study of environmental influences on an organism's genome [1]. Third, it investigates ethical, legal, and social dimensions of human relationships with other species, acknowledging the dynamic nature of environments that connect humans to nature in interdependent ways [1].

The One Health Approach and Ecological Genome Project

Central to the CELS Ecogenomics framework is the One Health approach, defined as "an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems" [1]. This approach provides a common language and knowledge framework that underpins environmental-genomic research, recognizing that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems are closely linked and interdependent [1] [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic particularly illustrated these connections through narratives involving contact with bats, lockdowns with companion animals, limited access to nature, and the "social lives" of microorganisms [1].

CELS has proposed an aspirational Ecological Genome Project inspired by the ambitious global endeavor of the Human Genome Project [1]. This project aims to connect an ecology built around genomic sequencing of the world around us to human genomics, expanding human ecology into a grand vision of our "home" (from the Greek oikos)—the biosphere of Planet Earth [1]. The project seeks to build on the significance of genes to cultures with natural history, connecting molecular and exposome studies of human and non-human life within shared environments and communities [1].

Ecogenomics Framework and Relationships

Methodological Approaches and Research Protocols in Ecogenomics

Interdisciplinary Research Framework

The CELS vision for Ecogenomics requires methodological integration across multiple disciplines to effectively study connections between human genomes and natural systems. This approach necessitates breaking down traditional academic silos and creating novel collaborative structures that can address the complexity of genome-environment interactions [1]. The methodological framework incorporates both empirical observation and ethical reflection, recognizing that scientific and ethical inquiries are inherently intertwined in this domain [2].

The Socratic Workshop model employed by CELS at the Brocher Foundation in Geneva (2024) exemplifies this integrative approach, bringing together geneticists, bioethicists, legal scholars, genetic counselors, and ecologists to develop a comprehensive understanding of Ecogenomics [2]. This workshop methodology facilitates deep interdisciplinary dialogue that connects genomic theory with empirical observations from field, laboratory, and clinical settings [2]. The outcome of such engagements is a refined conceptual framework that acknowledges HUGO's evolving role to include environmental research and advocates for widening the study of reciprocal interactions between genomic sciences and ecological systems [2].

Experimental and Analytical Workflows

Ecogenomics research employs sophisticated experimental workflows that span molecular analyses to ecosystem-level observations. The field utilizes environmental DNA (e-DNA) approaches to study biodiversity and ecosystem health, while comparative genomic analyses reveal diversity across non-human species [1]. Multi-omics integration represents a core methodological challenge, requiring coordinated analysis of genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and exposomic data within ecological contexts [1].

Table: Ecogenomics Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Tools

| Research Component | Essential Materials/Reagents | Function in Ecogenomics Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Environmental DNA sampling kits | Captures genetic material from various environmental sources (soil, water, air) |

| Genomic Sequencing | Next-generation sequencing platforms | Generates comprehensive genomic data from diverse biological specimens |

| Data Analysis | Bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., VariantValidator) | Standardizes variant naming and facilitates data integration across studies [2] |

| Variant Interpretation | MANE Select transcripts | Provides consistent reference for transcript selection and annotation [2] |

| Ethical Framework | Benefit-sharing protocols | Ensures equitable distribution of research benefits per Nagoya Protocol [1] |

The methodological approach also includes careful consideration of ethical dimensions throughout the research process. This includes implementing benefit-sharing mechanisms in accordance with the Nagoya Protocol, which requires fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources [1]. Research design must incorporate community engagement practices and respect for Indigenous data sovereignty, recognizing that different communities may have distinct relationships with and rights over genetic resources [1].

Ecogenomics Research Workflow

Key Research Areas and Strategic Directions

Biodiversity Conservation and Genomic Research

CELS has emphasized the critical importance of genomic research for achieving the targets set forth in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which includes protecting 30% of terrestrial and marine areas by 2030 and effectively reducing anthropogenic pollution [1]. Genomic institutions are recognized as having direct and indirect impacts on biodiversity through their use of ecosystem services, responsibility to reduce negative impacts, production of benefits related to environmental determinants of health, and implementation of appropriate biosafety measures [1].

CELS recommends that genomic scientists adapt their work to support sustainable futures by contributing to interdisciplinary research aimed at stabilizing ecological determinants of health [1]. This requires cultural and social responsiveness to different community perspectives and engagement with international governance challenges related to genetic resources [1]. The committee specifically advocates for genomic research that acknowledges the rights of nature and Mother Earth, as affirmed in the Kunming-Montreal Framework, while also addressing the collective need for healthy food, water, energy, and air [1].

Ethical Governance and Data Sovereignty

A central research priority for CELS involves reexamining the ethics and law of data sovereignty in the context of population-specific genomic variation [2]. This work builds on historical HUGO statements, including the 1996 Statement on the Principled Conduct of Genetics Research that first recognized "the human genome is part of the common heritage of humanity," and the 2000 Statement on Benefit Sharing that called for dedicating a percentage of commercial profit to public healthcare infrastructure and humanitarian efforts [1] [5].

CELS is currently coordinating workshops to revisit these foundational statements and develop updated guidance that reflects contemporary ELSI issues, particularly regarding how local reference databases will combine with global genomic diversity initiatives [2]. This work aligns with the World Health Organization's 2024 guidance for human genome data collection, access, use, and sharing, which aims to "Promote the use of common principles in laws, policies, frameworks and guidelines, within and across countries and contexts" [2]. The committee's approach balances global framing with national interests while maintaining core commitments to genomic solidarity and egalitarian access to scientific benefits [1] [8].

Implementation and Global Impact

Translating Ecogenomics into Practice

The implementation of Ecogenomics principles requires concrete strategies for bridging scientific discovery and practical application. CELS advocates for research that connects molecular analyses of environmental influences on genomes with tangible interventions that promote ecosystem health [1]. This translational approach acknowledges that patterns of molecular, genetic, and epigenetic change must be studied in ways that account for communities' complex social histories, exposures to stress, and access to basic resources and opportunities that promote community health [1].

CELS promotes the development of standardized nomenclature and data sharing practices to facilitate Ecogenomics research. Recent updates to the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) Nomenclature have improved machine readability while maintaining human interpretability, featuring refined syntax for gene fusion descriptions and recommendations for MANE Select transcripts [2]. Similarly, implementation of VariantValidator helps standardize variant naming in scientific literature to increase diagnostic rates and improve data consistency across studies [2]. These technical standards support the broader goals of Ecogenomics by enabling more effective collaboration and data integration across traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Future Directions and Scientific Agenda

Looking forward, CELS has identified several priority areas for advancing Ecogenomics research and implementation. The committee has proposed including environmental sessions at future Human Genome Meetings that are inclusive of ecology and conservation genome specialists [2]. These sessions would provide forums for presenting research on ecological dimensions of health, environmental DNA (e-DNA) applications, and comparative genomic diversity of non-human species [1].

CELS continues to develop its conceptual framework for Ecogenomics through ongoing scholarly publications and policy engagements. A manuscript on "The Ecological Genome Project and the Promises of Ecogenomics for Society" has been submitted to The Lancet Planetary Health, articulating a vision for realizing Ecogenomics through a One Health approach [2]. This work positions HUGO to contribute meaningfully to addressing what over two hundred health journals have recognized as a systemic "global health emergency" related to environmental degradation and biodiversity loss [2]. Through these efforts, CELS aims to ensure that genomic sciences evolve to address the pressing environmental challenges that societies face in the 21st century [1].

The One Health framework is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems. This approach recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent [9]. The concept has gained significant traction in recent years, particularly in response to global health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which underscored the intricate connections between human health, animal health, and ecosystem integrity [10]. The collaborative approach mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines, and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems [10].

The Quadripartite organizations – the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) – have jointly endorsed and promoted a comprehensive definition of One Health through the One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) [10]. This definition serves as the foundation for global efforts to implement the One Health approach, emphasizing the need for shared and effective governance, communication, collaboration, and coordination across sectors and disciplines [9]. The approach can be applied at community, subnational, national, regional, and global levels, making it a versatile framework for addressing complex health challenges.

The Ecogenomics Perspective: HUGO CELS Initiative

The Human Genome Organisation's Committee on Ethics, Law and Society (HUGO CELS) has proposed a visionary expansion of genomic sciences to include ecological considerations through the concept of Ecogenomics [1]. This initiative represents a significant alignment between genomics and the One Health approach, suggesting that an interdisciplinary One Health perspective should be adopted in genomic sciences to promote ethical environmentalism [1] [2].

The Ecological Genome Project is an aspirational opportunity to explore connections between the human genome and nature, providing a blueprint to respond to the environmental challenges that societies face [1]. HUGO CELS envisions Ecogenomics as comprising three core areas:

- Biotechnological applications of genomics to achieve Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to climate action and life on land and below water

- Study of environmental influences on the human genome, including the impacts of ambient agents on heritable variations and changes in the personal microbiome

- Ethical, legal, and social investigation of human relationships with other species, recognizing that human life on Earth relies on the diversity of other species [1]

This perspective has been formally endorsed by both HUGO CELS and the HUGO Executive Board, signaling a commitment to integrating environmental considerations into genomic research and applications [1].

Quantitative Foundations of One Health

The imperative for a One Health approach is supported by compelling quantitative data that demonstrates the interconnected nature of health threats across human, animal, and environmental domains.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence Supporting the One Health Approach

| Category | Statistic | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Disease Origins | 60% of human pathogens originate from animals [10] | Highlights the animal-human interface as a critical pathway for disease emergence |

| Emerging Diseases | 75% of emerging infectious diseases have an animal origin [10] | Underscores the importance of animal health surveillance for pandemic prevention |

| Bioterrorism Threats | 80% of potential bioterrorism pathogens originate in animals [10] | Links animal health to national security concerns |

| Food Security | 20% of animal production losses linked to diseases [10] | Demonstrates the economic impact of animal health on food systems |

| Deforestation Impact | >25% forest cover loss increases human-wildlife contact [10] | Shows environmental change as a driver of disease transmission |

| Environmental Alteration | 75% of terrestrial environments altered by humans [10] | Illustrates the scale of human impact on ecosystems |

Table 2: Economic and Social Dimensions of One Health Challenges

| Factor | Impact | One Health Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Global Hunger | 811 million people go to bed hungry each night [10] | Connects health of agricultural systems to food security |

| Future Protein Demand | >70% more animal protein needed by 2050 [10] | Projects increasing pressure on animal health systems |

| Poverty Connections | >75% of people living on <$2/day depend on livestock [10] | Links animal health to economic resilience of vulnerable populations |

These quantitative findings demonstrate that effective management of global health threats requires an integrated approach that addresses the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health systems.

Operationalizing One Health: Implementation Frameworks

Global Implementation Architecture

The One Health Joint Plan of Action (OH JPA), developed by the Quadripartite organizations, provides a comprehensive framework for implementing One Health approaches at global, regional, and national levels [9] [10]. This framework is organized around six interdependent Action Tracks:

- Enhancing capacity to strengthen health systems under a One Health approach

- Reducing risks from emerging zoonotic epidemics and pandemics

- Controlling and eliminating endemic zoonotic diseases

- Strengthening assessment and management of food safety risks

- Curbing antimicrobial resistance (AMR)

- Better integrating the environment into One Health [10]

The OH JPA is supported by an implementation guide that describes three pathways and a five-step process for countries to adopt and adapt the plan to strengthen and support national One Health actions [10].

National Implementation: U.S. National One Health Framework

The United States has developed its first-ever National One Health Framework to Address Zoonotic Diseases and Advance Public Health Preparedness (2025-2029) [11]. This framework, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Department of the Interior (DOI) in response to a Congressional mandate, provides a strategic approach to One Health implementation that includes:

- Establishing a structured platform for cross-agency communication, training, and information sharing

- Formalizing the integration of human, animal, and environmental health data to improve disease threat monitoring

- Creating a system that can be applied to complex public health challenges beyond zoonotic diseases [12]

This national framework represents a significant advancement in operationalizing One Health principles through coordinated government action.

Ecogenomics Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Metagenomic Approaches in Ecogenomics

Metagenomic sequencing represents a cornerstone methodology in ecogenomics research, enabling comprehensive analysis of genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples. The following workflow illustrates a standardized protocol for viral ecogenomics studies based on recent research in marine systems [3]:

Diagram 1: Viral ecogenomics workflow for aquatic samples. This standardized protocol enables characterization of viral communities and their functional potential in environmental samples.

Multiomics and Ecological Spatial Analysis (MESA)

The MESA framework represents an advanced methodological approach that integrates spatial omics with single-cell datasets and applies ecological principles to analyze tissue organization [13]. This approach introduces several innovative metrics:

- Multiscale Diversity Index (MDI): Evaluates diversity variations across spatial scales

- Global Diversity Index (GDI): Assesses whether patches of similar diversity are spatially adjacent

- Local Diversity Index (LDI): Distinguishes regions by their diversity patterns and identifies 'hot spots' and 'cold spots'

- Diversity Proximity Index (DPI): Evaluates spatial relationships among hot/cold spots [13]

The MESA pipeline involves several key steps, beginning with the integration of spatial omics with corresponding single-cell datasets from the same tissue type and disease condition using MaxFuse [13]. The framework then characterizes the local neighborhood of each cell to identify conserved, distinct cellular neighborhoods by aggregating multiomics information from spatially determined neighbors. Subsequent steps include using k-means clustering to identify conserved neighborhood patterns, followed by differential expression analysis and gene set enrichment analysis to explore functional pathways and implications [13].

Forensic Ecogenomics Applications

Ecogenomics methodologies have been adapted for forensic applications, particularly in estimating post-mortem intervals through characterization of soil microbial communities. The forensic ecogenomics approach involves:

- Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS) to characterize soil microbial communities in graves with remains

- Analysis of microbial succession patterns from early to skeletal stages of decomposition

- Estimation of post-burial interval (PBI) based on temporal changes in gravesoil microbiology

- Detection of post-translocation interval (PTI) for remains that have been moved from primary deposition sites [14]

This application demonstrates how ecogenomics methodologies can be adapted to address specific practical challenges while maintaining rigorous scientific standards.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ecogenomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Ecogenomics Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals) [3] [15] | DNA extraction from environmental samples | Efficient lysis of difficult-to-break environmental microorganisms, including Gram-positive bacteria | DNA extraction from viral particles concentrated from marine blue holes [3] |

| PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories) [15] | DNA extraction from soil and water samples | Removal of PCR inhibitors (humic acids, phenols) while maintaining DNA yield | Processing freshwater lake samples for CPR bacteria study [15] |

| VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme) [3] | Library preparation for metagenomic sequencing | Fragmentation, end repair, adapter ligation, and library amplification for Illumina platforms | Preparation of viral metagenome libraries from Yongle Blue Hole [3] |

| ZR Soil Microbe DNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research) [15] | DNA purification from soil filters | Rapid purification of microbial DNA from soil and filter samples | DNA extraction from 0.22μm filters of lake water samples [15] |

| Polycarbonate membrane filters (0.22μm, Millipore) [3] [15] | Sample collection and fractionation | Size-based separation of microbial cells and viral particles from environmental samples | Collection of "cellular fraction" (>0.22μm) and "viral fraction" (<0.22μm) [3] |

| Amicon centrifugal devices (100 kDa) [3] | Viral concentration | Concentration of viral particles from large volume water samples | Concentrating viral particles after iron chloride flocculation [3] |

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Networks in Ecogenomics

Ecogenomics research has revealed complex metabolic interactions between viruses and their microbial hosts in various ecosystems. Analysis of viral metagenomes from stratified environments like the Yongle Blue Hole has identified diverse auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) that influence key biogeochemical cycles [3]:

Diagram 2: Viral influence on host metabolic pathways. Viruses can significantly impact ecosystem functioning through expression of auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) that reprogram host metabolism during infection.

The functional significance of these AMGs is particularly evident in stratified environments like the Yongle Blue Hole, where viral communities in different redox zones contain distinct complements of metabolic genes [3]. In the oxic layer, viral AMGs may influence photosynthetic processes, while in the anoxic zone, they predominantly affect chemosynthetic pathways and sulfur metabolism [3]. This differential distribution of metabolic capabilities demonstrates how virus-host interactions are finely tuned to local environmental conditions.

Integrated Case Studies and Applications

Successful One Health Implementation: Rabies Control in Sri Lanka

A documented example of successful One Health implementation is the rabies control program in Sri Lanka, which employed a coordinated, multi-sectoral approach to address a persistent zoonotic disease [12]. The program included several key components:

- Mass canine vaccination: Large-scale, strategic vaccination of the dog population to control virus spread at its source

- Human vaccination and public awareness: Implementation of human post-exposure prophylaxis and public education campaigns

- Dog population management: Development of effective strategies for managing dog populations

- Cross-sectoral collaboration: Integration of expertise from health officials, veterinarians, and public health epidemiologists [12]

This comprehensive approach yielded significant results, with human fatalities from rabies dropping to less than 50 in 2012 following implementation of the One Health strategies [12]. This case demonstrates the practical effectiveness of using a multi-disciplinary approach to address a complex zoonotic disease.

One Health in Pandemic Response: COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a real-world test of One Health principles and highlighted both the value of cross-sectoral collaboration and the need for stronger implementation of the One Health approach [9] [10]. During the pandemic, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention coordinated the One Health Federal Interagency Coordination Committee, which brought together more than 20 federal agencies to respond to the pandemic [12]. Key activities included:

- Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 spread between people and animals

- Development of guidance for companion animals, wildlife, and food production animals

- Integration of surveillance and genomic data from human and animal samples to understand viral transmission patterns [12]

The pandemic underscored the necessity of strengthening cross-sectoral collaboration, increasing policy coordination, and promoting the development of integrated indicators to address upstream drivers of disease, with a focus on prevention [9].

Future Directions and Research Agenda

The future development of the One Health framework and its integration with ecogenomics involves several critical frontiers:

Methodological Innovations

Advancements in multiomics integration and spatial analysis will be essential for unraveling the complex interactions between humans, animals, and ecosystems. The MESA framework represents a promising approach that combines ecological principles with multiomics data to quantify tissue states and spatial organization [13]. Similar approaches could be adapted to environmental samples to better understand ecosystem health states.

Further development of standardized protocols for ecogenomics research across different ecosystems will enhance data comparability and meta-analysis potential. Methodological consistency is particularly important for long-term monitoring of ecosystem health and for detecting subtle changes that may signal emerging health threats.

Expanded Implementation Frameworks

The One Health Joint Plan of Action provides a foundation for systematic implementation of One Health principles at national and regional levels [10]. Future efforts should focus on:

- Developing indicators and monitoring frameworks to track One Health implementation progress

- Strengthening governance mechanisms for cross-sectoral collaboration

- Building capacity for One Health approaches in both developed and developing countries

- Enhancing data sharing across human, animal, and environmental health sectors

The HUGO CELS initiative on Ecogenomics aligns with this expanded implementation framework by advocating for the inclusion of environmental considerations in genomic research and policy [1] [2]. This integration of genomic sciences with environmental health represents an important frontier in the evolution of the One Health approach.

The One Health framework provides an essential paradigm for addressing complex health challenges at the interface of humans, animals, and ecosystems. The integration of ecogenomics approaches through initiatives like HUGO CELS's Ecological Genome Project expands the scope of traditional genomic sciences to encompass environmental dimensions, creating new opportunities for understanding and managing health in an interconnected world.

The quantitative evidence supporting One Health implementation, combined with developing methodological frameworks like MESA and standardized ecogenomics protocols, provides a robust foundation for advancing this integrated approach to health. As demonstrated by successful applications in rabies control, pandemic response, and environmental monitoring, the One Health framework offers practical solutions to real-world health challenges while promoting sustainable balance among human, animal, and ecosystem health.

Ecogenomics represents a paradigm shift in biological sciences, integrating genomic technologies with ecological principles to study organisms within their natural environments. This field enables researchers to decipher the complex interactions between genomic information, environmental factors, and ecosystem dynamics without the necessity of laboratory cultivation. For the HUGO Committee CELS perspective research, ecogenomics provides a foundational framework for understanding how genomic elements function within environmental contexts, offering transformative insights for biotechnology development, therapeutic discovery, and environmental management. Through high-throughput sequencing and computational analysis, ecogenomics reveals the vast functional potential encoded within environmental microbiomes, illuminating previously inaccessible biological diversity and metabolic capabilities that drive global biogeochemical cycles.

Core Area I: Biotechnology and Applied Genomics

Metabolic Pathway Discovery and Engineering

Ecogenomics enables the identification of novel metabolic pathways from uncultivated microorganisms with significant biotechnological potential. Patescibacteria (CPR), for instance, exhibit highly reduced genomes with unique metabolic traits that inspire innovative bioprocessing strategies. Research on freshwater lake microbiomes has revealed that despite their metabolic dependence, certain CPR lineages encode ion-pumping rhodopsins and heliorhodopsins that may function in light-energy capture and oxidative stress mitigation [16]. These molecular systems offer templates for developing novel optogenetic tools and biosensors. Additionally, the discovery of carbohydrate-active enzymes in permafrost lake CPR genomes indicates potential for biotechnology applications in biomass conversion and biofuel production [16].

Table 1: Biotechnologically Relevant Genes Identified Through Ecogenomic Studies

| Gene/Pathway | Source Organism | Potential Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-pumping rhodopsins | Freshwater CPR | Optogenetics, bioenergy | [16] |

| Heliorhodopsins | Freshwater CPR | Oxidative stress protection | [16] |

| Carbohydrate-active enzymes | Permafrost lake CPR | Biofuel production, bioremediation | [16] |

| Auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) | YBH viruses | Metabolic engineering | [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Bioprospecting

Metagenomic Library Construction and Screening Protocol:

Sample Collection: Filter 20-60L of water through sequential 20-μm, 5-μm, and 0.22-μm polyethersulfone membrane filters until complete clogging occurs [16] [17].

DNA Extraction: Utilize commercial kits (e.g., PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil) with modifications for environmental samples. For difficult-to-lyse organisms, incorporate bead-beating steps [16] [17].

Library Preparation: Employ VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina V3 or similar systems. Size selection is critical for capturing complete operons and gene clusters [17].

Sequencing: Perform on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq 6000, NextSeq 500) with 2×151 bp paired-end reads for optimal assembly [16] [17].

Functional Screening: Clone large-insert fragments (fosmid, BAC) into heterologous hosts. Screen for activities of interest using phenotypic assays or sequence-based analyses [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ecogenomics Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Function in Ecogenomics |

|---|---|---|

| PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | MoBio Laboratories | Extracts high-quality DNA from difficult environmental matrices |

| FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil | MP Biomedicals | Efficient lysis of diverse microorganisms including recalcitrant species |

| Polyethersulfone membrane filters (0.22μm) | Millipore | Size-fractionation of microbial cells and viral particles |

| VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit | Vazyme | Preparation of sequencing libraries from low-input DNA |

| ZR Soil Microbe DNA MiniPrep Kit | Zymo Research | Rapid purification of microbial DNA with inhibitor removal |

Core Area II: Environmental Influences on the Genome

Genome Reduction and Adaptation Mechanisms

Environmental pressures exert profound influences on genomic architecture, driving adaptive evolution through gene loss, horizontal transfer, and functional specialization. Studies of Patescibacteria in freshwater lakes reveal extensive genome reduction as an adaptation to nutrient-rich host-associated niches. These organisms display median genome sizes of approximately 1 Mbp – significantly smaller than free-living bacteria – with corresponding reductions in metabolic capabilities [16]. This streamlining results in loss of biosynthetic pathways for amino acids, nucleotides, and lipids, creating metabolic dependencies that dictate symbiotic lifestyles. Environmental factors such as oxygen availability further shape genomic content, selecting for specialized systems including terminal oxidases for O₂ scavenging and fermentative metabolic pathways for energy generation in anoxic conditions [16].

Genomic Signatures of Environmental Stress

Ecogenomic analyses identify characteristic genomic features associated with environmental stress responses. In the stratified ecosystems of Yongle Blue Hole, viral communities demonstrate redox-dependent diversification, with anoxic zones harboring novel viral genera distinct from oxic waters [17]. Prokaryotic genomes from these environments encode stress response systems, including DNA repair mechanisms and oxidative stress mitigation pathways. The prevalence of heliorhodopsins in CPR genomes suggests photoprotective functions against light-induced damage in surface waters [16]. These genomic adaptations represent functional conservation shaped by environmental constraints, providing insights into evolutionary processes under extreme conditions.

Table 3: Environmental Factors and Associated Genomic Adaptations

| Environmental Factor | Genomic Adaptation | Organisms Observed | Functional Consequence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen limitation | Terminal oxidases for O₂ scavenging | Freshwater CPR | Protection from oxidative damage | [16] |

| Host association | Genome reduction | Patescibacteria | Metabolic dependency | [16] |

| Nutrient scarcity | Auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) | YBH viruses | Host metabolic reprogramming | [17] |

| Light exposure | Rhodopsins & heliorhodopsins | Freshwater CPR | Energy capture & stress mitigation | [16] |

Protocol for Assessing Environmental Influences on Genomes

Integrated Metagenomic and Fluorescence Analysis Protocol:

Sample Collection Across Gradients: Collect samples across environmental transects (e.g., depth profiles, oxygen gradients) using Niskin bottles or similar devices [17].

Catalyzed Reporter Deposition-FISH (CARD-FISH):

- Fix samples with paraformaldehyde (3% final concentration)

- Apply horseradish peroxidase-labeled oligonucleotide probes targeting specific phylogenetic groups

- Amplify signal via tyramide deposition

- Visualize using epifluorescence or confocal microscopy [16]

Metagenomic Assembly: Assemble sequences using MEGAHIT v1.1.4-2 with k-mer sizes: 29, 49, 69, 89, 109, 119, 129, and 149 [16].

Bin Extraction and Validation: Extract metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using MetaBAT2 with tetranucleotide frequencies and coverage data. Assess completeness using single-copy genes (SCGs) and remove contaminants [16].

Comparative Genomics: Annotate genomes via Prodigal v2.6.3 and compare functional profiles across environmental conditions to identify habitat-specific adaptations [16] [17].

Core Area III: Dynamic Ecosystems and Microbial Interactions

Viral-Mediated Ecosystem Engineering

Viruses serve as crucial ecosystem engineers in dynamic environments, modulating microbial communities and biogeochemical cycles through host infection and lysis. In the Yongle Blue Hole ecosystem, viral communities demonstrate distinct stratification across redox gradients, with anoxic zones containing a high proportion of novel viral genera (classes Caudoviricetes and Megaviricetes) compared to oxic layers [17]. These viruses encode auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) that potentially manipulate host metabolic pathways during infection, impacting photosynthesis, methane metabolism, nitrogen cycling, and sulfur transformations [17]. Through these mechanisms, viruses directly influence carbon and nutrient fluxes in stratified ecosystems, demonstrating their integral role in ecosystem dynamics.

Host-Associated Lifestyles and Ecosystem Function

Microbial interactions fundamentally shape ecosystem processes, with host-associated lifestyles representing key ecological strategies. Ecogenomic studies reveal that Patescibacteria employ diverse lifestyle strategies ranging from obligate symbiosis to potential free-living existence [16]. CARD-FISH analyses show distinct CPR lineages (ABY1, Paceibacteria, Saccharimonadia) either attached to host organisms, associated with 'lake snow' particles, or existing in free-living states [16]. These interaction modalities influence organic matter transformation, with particle-associated CPR potentially contributing to complex carbon degradation in lacustrine systems. The detection of carbohydrate-active enzymes in freshwater CPR genomes supports their role in processing dissolved organic matter, linking microbial interactions to broader ecosystem functions [16].

Methodologies for Studying Ecosystem Dynamics

Viral Ecogenomics Workflow for Ecosystem Analysis:

Viral Particle Concentration:

- Pre-filter water through 0.22-μm membranes to remove cellular material

- Concentrate viral particles via iron chloride flocculation

- Resuspend in ascorbic-EDTA buffer (0.1 M EDTA, 0.2 M MgCl₂, 0.2 M ascorbic acid, pH 6.0)

- Further concentrate using 100 kDa Amicon centrifugal devices [17]

Viral Metagenome Processing:

- Identify viral contigs using VirSorter2 (score ≥ 0.9), VIBRANT, and DeepVirFinder (score ≥ 0.9, p < 0.1)

- Assess viral contigs with CheckV v.0.8.1 to determine virus-host boundaries

- Cluster ≥5 kb viral contigs into vOTUs using CD-HIT (95% identity, 85% coverage) [17]

Host-Virus Linkage:

- Predict open reading frames with Prodigal v2.6.3

- Identify prokaryotic hosts using CRISPR spacers, tRNA matches, and sequence homology

- Annotate AMGs by comparing to functional databases [17]

Network Analysis:

- Construct gene-sharing networks to visualize viral relatedness across ecosystems

- Identify habitat-specific viral populations and cross-ecosystem distributions [17]

Quantitative Ecosystem Profiling

Table 4: Distribution of Microorganisms Across Dynamic Ecosystems

| Ecosystem Type | CPR Prevalence | Dominant CPR Classes | Viral Diversity (vOTUs) | Key Metabolic Processes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater Lakes (hypolimnion) | 162 MAGs recovered | ABY1, Paceibacteria, Saccharimonadia | Not assessed | Fermentation, O₂ scavenging | [16] |

| Yongle Blue Hole (oxic zone) | Not specified | Not specified | Overlaps with open ocean | Photosynthesis, assimilatory sulfur reduction | [17] |

| Yongle Blue Hole (anoxic zone) | Patescibacteria detected | Not specified | High novel diversity | Methane, nitrogen, and sulfur metabolism | [17] |

| Groundwater (reference) | High diversity | Gracilibacteria, Saccharimonadia | Not assessed | Fermentation, host dependence | [16] |

Integrated Research Applications

Cross-Domain Methodological Integration

The power of ecogenomics lies in integrating approaches across its three core areas to address complex biological questions. The HUGO Committee CELS perspective benefits from this integration through improved functional annotation of genomic elements in environmental contexts. For instance, combining single-cell genomics with metatranscriptomics can validate predicted functions of uncultivated organisms, while CARD-FISH spatially localizes these functions within environmental gradients [16]. Similarly, coupling viral metagenomics with host activity measurements reveals how viral reprogramming influences ecosystem-scale processes [17]. These integrated approaches bridge the gap between genomic potential and ecological reality, offering a more complete understanding of biological systems.

Computational Framework for Ecogenomic Integration

FUNCODE Analysis for Functional Conservation:

Data Integration: Combine genomic data from mismatched environmental samples using in silico matching algorithms [18].

Functional Profiling: Annotate regulatory elements and metabolic pathways across phylogenetic boundaries.

Conservation Scoring: Quantify functional conservation of DNA elements across species and ecosystems.

Cross-Validation: Apply findings to predict new cis-regulatory elements and identify discoveries translatable across species [18].

This computational framework enables researchers to distinguish conserved functional elements from context-specific adaptations, facilitating identification of core biological processes with broad relevance to human health and disease.

Ecogenomics provides a powerful integrative framework that connects genomic information to environmental context and ecosystem function. For the HUGO Committee CELS perspective research, this approach offers unprecedented insights into how genomic elements function within natural systems, with significant implications for understanding gene-environment interactions relevant to human health. The three core areas – biotechnology applications, environmental influences on genomes, and dynamic ecosystem processes – collectively advance our ability to discover novel biological mechanisms, understand adaptive evolution, and predict ecosystem responses to environmental change. As methodological innovations continue to enhance our resolution of environmental genomics, ecogenomics will increasingly inform therapeutic development, diagnostic strategies, and our fundamental understanding of life's complexity across biological scales.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework as a Catalyst

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) represents a transformative global agreement adopted in 2022 with 23 action-oriented targets for 2030 and 4 long-term goals for 2050. This technical analysis examines how the GBF serves as a catalytic instrument for advancing the emerging field of Ecogenomics—the study of genomes within their social and natural environments. From the perspective of the HUGO Committee on Ethics, Law and Society (CELS), the framework provides essential scaffolding for interdisciplinary research bridging genomic sciences, ecology, and conservation biology. The GBF's robust monitoring infrastructure, commitment to equitable benefit-sharing, and emphasis on the One Health approach collectively establish unprecedented research imperatives and practical methodologies for investigating the complex relationships between human genomes, biodiversity, and planetary health. This whitepaper provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with technical protocols and analytical frameworks for aligning ecogenomics research with global biodiversity targets.

Historical Context and Adoption

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework was formally adopted in December 2022 during the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity. This historic agreement culminated from a four-year consultation and negotiation process, establishing an ambitious pathway toward achieving the global vision of "a world living in harmony with nature by 2050" [19]. The framework builds upon previous strategic plans and supports the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals while introducing specific, measurable targets for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use.

The GBF's adoption coincided with the Fourth Meeting of the Parties to the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization, highlighting the interconnectedness of genetic resource governance and biodiversity conservation [20]. This temporal alignment underscores the framework's relevance to genomic sciences and establishes new ethical and operational parameters for research involving genetic resources.

Structural Components of the GBF

The framework is organized around several core structural elements that guide its implementation:

- 4 Goals for 2050: Long-term outcome-oriented goals focusing on ecosystem integrity, species conservation, sustainable use, and resource mobilization

- 23 Targets for 2030: Action-oriented targets addressing reduced threats to biodiversity, meeting people's needs through sustainable use, and tools/ solutions for implementation [19]

- Comprehensive Implementation Package: Supporting decisions on monitoring framework, planning mechanisms, financial resources, capacity development, and digital sequence information [19]

This structured approach enables systematic progress assessment and facilitates the integration of biodiversity considerations across sectors and scientific disciplines, including genomic research.

Ecogenomics: Theoretical Foundation and GBF Alignment

Conceptual Framework and Definition

Ecogenomics represents an interdisciplinary field that investigates the complex relationships between genomes and their environmental contexts. The HUGO CELS perspective defines ecogenomics as "the conceptual study of genomes within the social and natural environment" [20]. This paradigm recognizes that the environment influences an organism's genome through multiple pathways, including ambient factors in the biosphere (climate, UV radiation), epigenetic and mutagenic effects of chemicals and pollution, and interactions with pathogenic organisms [21].

The Ecological Genome Project, proposed as an aspirational global initiative, aims to explore connections between the human genome and nature through integrated multi-omics approaches [20]. This project expands human ecology into a grand vision of our planetary 'home' (oikos), connecting molecular and exposome studies of human and non-human life within shared environments and communities.

One Health Integration

The GBF explicitly advocates for a One Health approach, recognizing the interconnectedness of human, animal, and ecosystem health [20]. This integrated perspective aligns fundamentally with ecogenomics principles, as it acknowledges that "the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment are closely linked and interdependent" [20]. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a powerful demonstration of these interconnections, illustrating how human-wildlife interactions, social behaviors, and environmental factors collectively influence health outcomes across species boundaries.

Table: Core Principles of Ecogenomics within the GBF Context

| Principle | Theoretical Foundation | GBF Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Embeddedness | Genomes are influenced by diverse environmental factors through epigenetic and mutagenic mechanisms | Targets 7, 8, and 13 addressing pollution, climate impacts, and agricultural management |

| Inter-species Connectivity | Genomic similarities between species reveal evolutionary relationships and shared vulnerabilities | Targets 4, 9, and 10 focusing on species conservation, wild species management, and sustainable agriculture |

| Benefit-sharing Ethics | Genetic resources should yield equitable benefits for conservation and community well-being | Target 13 on fair and equitable benefit-sharing from genetic resource utilization |

| Knowledge Integration | Traditional knowledge and scientific data collectively inform understanding | Target 21 on accessible data, information, and knowledge for decision-making |

GBF Targets as Research Catalysts: Technical Analysis

Direct Research Imperatives

Several GBF targets establish direct research imperatives for the ecogenomics community, creating specific catalytic opportunities:

Target 4: Species Recovery and Genetic Diversity This target requires "maintaining and restoring genetic diversity within and between populations of native, wild and domesticated species to maintain their adaptive potential" [22]. This establishes technical requirements for:

- Population genomic monitoring using neutral and adaptive genetic markers

- Assessment of effective population sizes (Ne) across taxa

- Development of genetic rescue strategies for threatened species

- Integration of in situ and ex situ conservation approaches

Target 7: Pollution Reduction The pollution reduction target specifically addresses "reducing the overall risk from pesticides and highly hazardous chemicals by at least half" [22]. This creates research imperatives for:

- Genomic and epigenomic assessments of chemical impacts on non-target species

- Development of biomarker systems for pollution monitoring

- Mechanistic studies of contaminant-induced mutagenesis

Target 13: Access and Benefit-Sharing This target mandates "fair and equitable sharing of benefits that arise from the utilization of genetic resources and from digital sequence information" [22]. This necessitates:

- Transparent provenance tracking for genetic resources

- Ethical frameworks for commercial application of biodiversity discoveries

- Equitable partnership models between researchers and source countries

Biodiversity Monitoring Infrastructure

The GBF establishes sophisticated monitoring requirements that directly enable ecogenomics research through standardized data collection and analysis frameworks. Target 21 specifically focuses on ensuring "the best available data, information and knowledge are accessible to decision makers, practitioners and the public" [23]. The monitoring framework for this target includes several technically rigorous components:

Table: Biodiversity Monitoring Components for Ecogenomics Research

| Monitoring Component | Technical Specification | Ecogenomics Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Diversity Metrics | Time series of censused abundances from populations monitored for effective population size with genetic markers | Tracking adaptive potential in changing environments; identifying populations at genetic risk |

| Species Information Index | Measurement of how well existing species occurrence data covers expected geographic ranges | Assessing landscape genomic connectivity; identifying sampling gaps for genetic resources |

| Ecosystem Condition Assessment | In situ and local knowledge of ecosystem structure and functioning | Correlating environmental parameters with genomic adaptation patterns |

| Traditional Knowledge Integration | Documentation of indigenous knowledge through frameworks like Indigenous Navigator | Incorporating locally-adapted genetic knowledge into conservation strategies |

The GBF monitoring framework emphasizes Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs)—a minimum set of critical variables required to study, report, and manage biodiversity change [24]. For ecogenomics, the genetic composition EBV class is particularly relevant, encompassing parameters such as genetic diversity, genetic differentiation, and inbreeding coefficients. Standardized measurement of these variables enables cross-taxa and cross-ecosystem comparisons essential for understanding broad ecological genomic patterns.

Methodological Protocols for GBF-Aligned Ecogenomics

Genomic Monitoring for Target 4 Compliance

Protocol Title: Landscape Genomic Assessment of Adaptive Potential in Threatened Species

Objective: To quantify neutral and adaptive genetic diversity in threatened species populations to inform GBF Target 4 implementation and assess adaptive potential under environmental change.

Materials and Reagents:

- Non-invasive sampling kits (feather, fur, scat, or tissue collection apparatus)

- DNA extraction and purification systems (e.g., silica membrane-based kits)

- Whole-genome sequencing or reduced-representation library preparation reagents

- Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) or RAD-seq kits for population assessment

- Environmental DNA (eDNA) filtration and concentration equipment

Methodology:

- Stratified Sampling Design: Establish sampling transects across environmental gradients and protection status categories (aligned with GBF Target 3 on protected areas)

- Non-invasive Sample Collection: Implement minimally-invasive sampling protocols to reduce research impact on threatened populations

- DNA Extraction and Quality Control: Extract genomic DNA with rigorous quality controls and quantification standards

- Sequencing Library Preparation: Utilize appropriate sequencing depth and coverage for population genomic inferences

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Alignment to reference genome (if available) or de novo assembly

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) calling with quality filtering

- Population structure analysis using clustering algorithms

- Detection of outlier loci under selection using FST-based methods

- Gene-environment association analysis using redundancy analysis or latent factor mixed models

- Genetic Diversity Metrics Calculation:

- Observed and expected heterozygosity

- Allelic richness

- Inbreeding coefficients (FIS)

- Effective population size (Ne) estimation using linkage disequilibrium or temporal methods

- Data Reporting and Submission: Submit raw sequences to public repositories (e.g., INSDC databases) and occurrence data to GBIF with complete metadata

Implementation Considerations:

- Engage indigenous peoples and local communities in sampling design with free, prior, and informed consent [23]

- Integrate traditional ecological knowledge with genomic data interpretation

- Align monitoring efforts with national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs)

Benefit-Sharing Framework for Genetic Resource Research

Protocol Title: Ethical Access and Benefit-Sharing for Genomic Research on Genetic Resources

Objective: To establish legally and ethically compliant procedures for accessing genetic resources and ensuring fair and equitable benefit-sharing in accordance with GBF Target 13 and the Nagoya Protocol.

Materials and Documentation:

- Prior Informed Consent (PIC) templates

- Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT) documentation

- Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs)

- Traditional Knowledge Associated (TKA) recording equipment

- Digital Sequence Information (DSI) provenance tracking systems

Methodology:

- Due Diligence Assessment: Research applicable access and benefit-sharing legislation in provider country

- Stakeholder Identification: Identify relevant indigenous peoples and local communities with rights or interests in target genetic resources

- Prior Informed Consent Negotiation: Engage rights-holders in culturally appropriate consultation processes to secure PIC

- Mutually Agreed Terms Establishment: Negotiate MAT covering:

- Non-monetary benefits (capacity building, technology transfer, research participation)

- Monetary benefits (royalty sharing, research funding contributions)

- Intellectual property arrangements

- Traditional knowledge protection measures

- Research Implementation with Provenance Tracking: Maintain chain of custody documentation throughout research process

- Benefit Implementation: Fulfill benefit-sharing obligations throughout research lifecycle

- Transparency Reporting: Publicly disclose research outcomes and benefit-sharing implementation

Implementation Considerations:

- Establish community advisory boards for long-term research programs

- Incorporate fair benefit-sharing principles into institutional policies