Ecogenomic Signatures in Bacteriophage Genomes: From Microbial Tracking to Precision Therapies

Bacteriophage ecogenomic signatures—distinct genetic patterns reflecting their microbial habitat—are emerging as powerful tools for diagnosing ecosystem health, tracking contamination sources, and developing precision antimicrobials.

Ecogenomic Signatures in Bacteriophage Genomes: From Microbial Tracking to Precision Therapies

Abstract

Bacteriophage ecogenomic signatures—distinct genetic patterns reflecting their microbial habitat—are emerging as powerful tools for diagnosing ecosystem health, tracking contamination sources, and developing precision antimicrobials. This article synthesizes current research for scientific and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles that underpin these habitat-specific signals. It details advanced methodologies for signature detection, including metagenomic and holo-transcriptomic approaches, and addresses key challenges in host prediction and data interpretation. By comparing signature stability across health and disease states, we highlight their validation as biomarkers for dysbiosis and their growing potential in combatting multidrug-resistant infections through engineered phage therapy, marking a new frontier in ecological and clinical microbiology.

Decoding the Habitat: The Origin and Principles of Phage Ecogenomic Signatures

Ecogenomic signatures are defined as habitat-specific genetic patterns embedded within bacteriophage genomes. These signatures arise from the co-evolution and adaptation of phages to specific microbial ecosystems, making them powerful diagnostic tools for tracking the origin and dynamics of microbial communities [1]. The core principle is that individual phages associated with a particular environment, such as the human gut, encode a distinct genetic profile. Homologues of these genes display a significantly higher relative abundance in metagenomes derived from that specific habitat compared to others [1]. This concept moves beyond single marker genes to encompass a genome-wide, habitat-associated signal.

The utility of these signatures is profound. A primary application is in Microbial Source Tracking (MST), where phage ecogenomic signatures can distinguish, for instance, human faecal contamination from that of other animals in environmental waters [1]. Furthermore, within the context of a broader thesis on phage ecogenomics, these signatures provide insight into ecosystem health. A recent meta-analysis revealed that while virome α-diversity changes variably during dysbiosis, a shift in viral β-diversity (community composition) is a more consistent signature of microbiome disturbance [2]. This breakdown in the predictable relationship between bacterial and phage diversity under disturbance suggests ecogenomic signatures could serve as broad indicators of ecosystem imbalance [2].

Key Experiments and Data

The foundational evidence for phage ecogenomic signatures was demonstrated through a series of comparative genomic and metagenomic analyses. The following table summarizes the quantitative findings from key experiments that established this concept.

Table 1: Experimental Evidence for Ecogenomic Signatures in Model Bacteriophages

| Bacteriophage (Habitat) | Analysis Type | Key Finding: Enrichment in Habitat | Statistical Significance & Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| ɸB124-14 (Human Gut) [1] | Viral Metagenomes | Significantly greater mean relative abundance of ORF homologues in human gut viromes vs. environmental viromes. | Yes (Significant); Profile distinct from marine and rhizosphere phages. |

| ɸB124-14 (Human Gut) [1] | Whole Community Metagenomes | Significantly greater representation in human-derived metagenomes vs. other body sites and environments. | Yes (Significant); Demonstrated detection in complex, non-viral metagenomes. |

| ɸSYN5 (Marine) [1] | Viral Metagenomes | Significantly greater representation in a subset of marine environment viromes vs. gut viromes. | Yes (Significant); Confirms habitat-specific signals are not unique to gut phages. |

| Virome Diversity (Multiple Hosts) [2] | Meta-Analysis (70 studies) | 69% of studies (47/68) reported a significant change in viral β-diversity with dysbiosis. | Highly consistent signature across diverse disease systems and hosts. |

| Virome Diversity (Multiple Hosts) [2] | Meta-Analysis (70 studies) | 89% of studies (62/70) reported significant enrichment of system-specific viral taxa under dysbiosis. | Indicates specific taxonomic shifts contribute to the ecogenomic signal. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing an Ecogenomic Signature

The following workflow details the methodology for identifying and validating an ecogenomic signature in a bacteriophage genome, based on established approaches [1].

Objective: To determine if a target bacteriophage genome encodes a genetic signature specific to a particular habitat (e.g., human gut).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Phage Genome Selection and Preparation:

- Select a bacteriophage of interest with a suspected habitat association (e.g., a phage infecting a common gut bacterium like Bacteroides fragilis).

- Ensure the phage genome is complete and accurately annotated. Follow rigorous guidelines for assembly, checking for terminal redundancies, circular permutation, and frameshift errors [3]. Tools like SPAdes or Shovill are recommended for de novo assembly, with read mapping verification using BWA-MEM or Bowtie2 [3].

Metagenomic Dataset Curation:

- Compile a diverse set of publicly available metagenomic datasets from the target habitat (e.g., human gut) and control habitats (e.g., marine, soil, bovine/porcine gut). These should include both viral-enriched (virome) and whole-community shotgun metagenomes.

Homology Search and Abundance Calculation:

- For each metagenomic dataset, use BLAST to identify all sequences with similarity to the open reading frames (ORFs) encoded by the target phage.

- Calculate the cumulative relative abundance of these phage ORF homologues within each metagenome. This metric normalizes the hit count by the total size of the metagenomic dataset.

Statistical Comparison and Signature Identification:

- Compare the cumulative relative abundance profiles of the target phage ORFs across all habitats using statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA).

- A statistically significant enrichment of ORF homologues in the target habitat (e.g., human gut) compared to non-target habitats indicates a positive ecogenomic signature.

- For validation, repeat the analysis with control phages of known habitat origin (e.g., a marine cyanophage). The control phage should show a distinct enrichment pattern (e.g., in marine metagenomes), confirming the specificity of the approach [1].

Discriminatory Power Assessment:

- Apply machine learning or clustering algorithms (e.g., PCA, random forests) to the ORF homologue abundance data to test if the signature can accurately segregate metagenomes based on their environmental origin.

- The signature's robustness can be further tested by challenging it with "contaminated" environmental metagenomes (e.g., simulated with in silico additions of human gut sequences) to see if it correctly identifies the pollution signal [1].

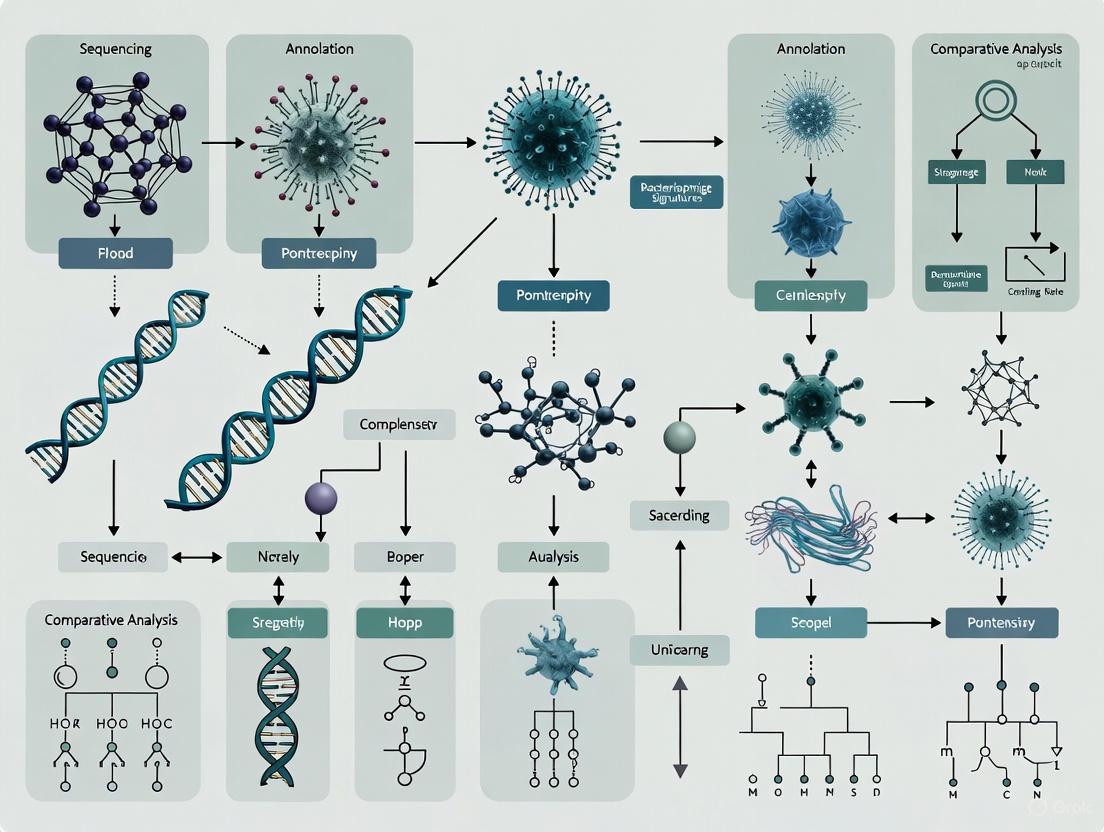

Diagram 1: Workflow for identifying a phage ecogenomic signature.

Data Visualization and Analysis

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting the complex data generated in ecogenomic studies. The field of untargeted metabolomics offers a parallel; its workflows are also highly dependent on expert "human-in-the-loop" input facilitated by visual tools that make abstract data tangible [4]. The following strategies are essential:

- Occupancy (Meta-)Plots: Show the average distribution of sequencing reads (e.g., from a metagenomic BLAST search) across a defined genomic region, such as the transcription start sites of host genes or the center of phage genomic islands. This reveals consistent patterns across many loci [5].

- Density Heatmaps: Display the signal strength of a habitat-specific signature (e.g., abundance of phage ORF homologues) for a large set of target genes or genomic intervals, ordered by a relevant metric. This allows for the visual identification of clusters with shared ecogenomic profiles [5].

- Comparative Visual Encodings: Use visualizations like UpSet plots instead of traditional Venn diagrams to clearly illustrate the complex intersections of phage genes present across multiple metagenomic habitats, especially when dealing with more than three sets [6].

The diagram below illustrates a proposed analytical pipeline for processing metagenomic data to extract and visualize these signatures.

Diagram 2: Data analysis pipeline for ecogenomic signatures.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section provides a curated list of essential reagents, software, and data resources for conducting research on phage ecogenomic signatures.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Phage Ecogenomics

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Relevance to Ecogenomic Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPAdes/Shovill [3] | Software (Assembler) | De novo assembly of phage genomes from sequencing reads. | Generates the high-quality, complete phage genomes required for downstream signature analysis. |

| PHASTER [7] | Web Server | Identification and annotation of prophage sequences within bacterial genomes. | Discovers cryptic phage elements in host genomes that may carry habitat-specific signals. |

| BLAST Suite [1] | Software (Alignment) | Finding regions of local similarity between phage sequences and metagenomic datasets. | The core tool for identifying homologues of phage ORFs in metagenomes to calculate abundance. |

| PhageTerm [3] | Software | Predicts phage genome termini type (e.g., circularly permuted, terminally redundant). | Confirms genome completeness and configuration, a critical prerequisite for accurate annotation. |

| VirNucPro/DeepPhage [8] | AI-Based Tool | Annotation of viral sequences using machine learning and language models. | Improves functional annotation of phage "dark matter," uncovering novel genes potentially contributing to signatures. |

| AlphaFold [8] | AI-Based Tool | Protein structure prediction from amino acid sequences. | Aids in functional prediction of orphan phage proteins, linking sequence to potential habitat-specific function. |

| RefSeq Genome Database [5] | Data Resource | Provides curated chromosome size and gene annotation files for various genome assemblies. | Essential for normalizing and mapping metagenomic data to a consistent genomic coordinate system. |

| MetaViralSPAdes [8] | Software (Assembler) | Metagenomic assembler specifically designed for viral sequences. | Recovers novel and divergent viral genomes from complex metagenomes, expanding the reference database. |

The concept of ecogenomic signatures refers to the distinct, habitat-associated genetic patterns encoded within bacteriophage genomes. These signatures arise from the prolonged co-evolution and adaptation of phages and their bacterial hosts within specific ecosystems. The genomic composition of an individual phage can serve as a diagnostic marker for its originating environment, reflecting the selective pressures and functional requirements of that niche. Research has demonstrated that individual phages, such as the gut-associated ɸB124-14, encode a clear habitat-related signal, with their gene homologues showing significantly different representation across viromes from different environments [1]. This foundational principle enables researchers to utilize phage genomes as robust indicators of microbial community structure and function.

The dynamics of the arms race between bacteria and phages are a primary evolutionary force shaping these signatures. Bacteria have developed sophisticated immune systems—including both passive adaptations (inhibiting phage adsorption, preventing DNA entry) and active defense systems (restriction-modification systems, CRISPR-Cas)—to counter phage infection [9]. In response, phages continuously evolve counter-measures, creating an ongoing molecular dialogue that leaves distinct evolutionary imprints on both parters' genomes. This co-evolutionary process generates the specific genetic patterns that constitute identifiable ecogenomic signatures [9] [1].

Quantitative Evidence of Phage-Ecosystem Relationships

Analysis of viral metagenomes (viromes) across habitats reveals that phages encode discernible ecological signals. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from a systematic review of 74 studies investigating virome signatures in dysbiosis:

Table 1: Virome Diversity Changes in Dysbiosis Across 74 Studies [2]

| Metric of Change | Number of Studies Reporting Significant Changes | Percentage of Studies | Directional Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-diversity (within-sample) | 28 out of 69 | 41% | Variable (58% decrease, 42% increase) |

| β-diversity (between-sample composition) | 47 out of 68 | 69% | More consistent signature of dysbiosis |

| Taxon Enrichment (specific viral taxa) | 62 out of 70 | 89% | System-specific viral taxa enriched |

Further evidence comes from studies tracking specific phage genes across environments. The relative abundance of gene homologues from the human gut-associated phage ɸB124-14 is significantly enriched in human gut viromes compared to environmental viromes, confirming that individual phage genomes can carry a strong habitat-specific signal [1]. Conversely, cyanophage SYN5, isolated from marine environments, shows the inverse pattern, with greater representation in marine metagenomes [1]. This indicates that the ecogenomic signature is a generalizable phenomenon applicable to phages from diverse habitats.

Table 2: Ecogenomic Signatures in Model Bacteriophages [1]

| Phage | Natural Habitat | Representation in Human Gut Viromes | Representation in Environmental Viromes | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ɸB124-14 | Human Gut (Bacteroides) | High | Low | p < 0.05 |

| ɸSYN5 | Marine (Cyanobacteria) | Low | High (Marine) | p < 0.05 |

| ɸKS10 | Plant Rhizosphere | Very Low | Very Low | Not Discernible |

A critical insight from meta-analysis is that the relationship between bacterial diversity and phage diversity follows ecological patterns. Bacterial α-diversity is a strong predictor of virome α-diversity in healthy states (mean r² = 0.380), but this correlation breaks down under dysbiosis (mean r² = 0.118) [2]. This decoupling during disturbance suggests that the phage-bacteria relationship is a key feature of ecosystem health and a potential diagnostic signature.

Protocols for Ecogenomic Signature Discovery

Protocol 1: Holo-Transcriptomic Profiling of Phage-Host Dynamics

Principle: This approach captures the entire transcriptome (host, bacteria, and phage) within a sample to identify transcriptionally active microbes and phage-host interactions, providing a dynamic view of community activity beyond mere presence/absence [10].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Acquisition & Storage: Collect biological material (e.g., stool, tissue, environmental sample) and immediately flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Store at -80°C to preserve RNA integrity.

- RNA Extraction: Use a commercial kit designed for co-extraction of total RNA, including small RNAs. Treat samples with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Host RNA Depletion: To enrich for microbial and viral transcripts, treat total RNA with a probe-based hybridization method (e.g., NuGEN's AnyDeplete) to remove abundant host ribosomal RNA.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Convert the depleted RNA into a sequencing library using a strand-specific protocol. Sequence on an Illumina platform to achieve a minimum of 20-30 million paired-end reads per sample.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Assess read quality using FastQC [10]. Trim adapters and low-quality bases (Q<30) using Cutadapt, removing reads shorter than 35-50 bp [10].

- Host Transcript Removal: Map reads to the host reference genome (e.g., human, mouse) and discard mapped reads.

- Metatranscriptomic Assembly: De novo assemble the remaining reads into contigs using a dedicated assembler (e.g., MEGAHIT, rnaSPAdes).

- Phage & AMR Gene Identification: Classify contigs using a combination of:

- Reference-based: Map reads to curated phage genome databases like PhageScope or IMG/VR using BWA-MEM or minimap2 [10].

- De novo: Use annotation tools like PhANNs or PhaGAA to identify phage-related contigs based on intrinsic genomic features [10].

- Functional Annotation: Annotate contigs against AMR gene databases (e.g., CARD, ARG-ANNOT) and general protein databases (e.g., UniProt, KEGG) to identify active antibiotic resistance genes and metabolic pathways.

<100: Holo-Transcriptomic Profiling Workflow

Protocol 2: Metagenomic Validation of Ecogenomic Signatures

Principle: This protocol uses whole-community or viral metagenomic sequencing to validate the habitat-specificity of phage-encoded ecogenomic signatures, as demonstrated for phage ɸB124-14 [1].

Experimental Workflow:

- Metagenomic Sample Collection: Obtain a set of metagenomes from distinct habitats (e.g., human gut, other mammalian guts, various environmental waters).

- Sequence Data Processing: Download quality-filtered metagenomic reads or assemblies from public repositories or process raw sequences through a standardized pipeline (quality control, adapter trimming).

- Ecogenomic Signature Quantification:

- Reference Selection: Choose one or more well-characterized phage genomes as reference ecogenomic signatures (e.g., ɸB124-14 for human gut).

- Homology Search: For each metagenome, perform a translated search (using BLASTX or DIAMOND) of all reads/contigs against the proteome of the reference phage.

- Calculate Cumulative Relative Abundance: For a given metagenome and reference phage, calculate the cumulative relative abundance (CRA) of its ORFs using the formula:

CRA = (Total number of valid hits to all phage ORFs) / (Total number of sequences in metagenome)

- Statistical Analysis & Discrimination:

- Compare the CRA values for the target phage across different habitats using statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test).

- Use the CRA profile to build a classification model (e.g., LDA, random forest) to discriminate metagenomes based on their environmental origin (e.g., contaminated vs. uncontaminated water) [1].

<100: Metagenomic Validation of Phage Signatures

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Ecogenomic Signature Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Phage Genome Databases | Reference for sequence-based identification and classification of phages. | PhageScope, IMG/VR, Microbe Versus Phage database [10]. |

| Phage Annotation Tools | De novo identification and functional annotation of phage sequences in omics data. | PhANNs, PhaGAA web servers [10]. |

| AMR Gene Databases | Annotation of antibiotic resistance genes in phage and bacterial genomic data. | CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) [10]. |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models | Generating context-rich protein embeddings for predicting phage-host interactions. | ProtBERT, ProT5 [11]. |

| Host Depletion Kits | Enrichment of microbial and viral RNA in holo-transcriptomic studies by removing host ribosomal RNA. | Commercial probe-based kits (e.g., NuGEN AnyDeplete) [10]. |

| AI-Based Genome Design Tools | Generating novel, functional phage genomes to explore sequence-function relationships and overcome resistance. | Evo genomic foundation models [12]. |

Advanced Predictive Modeling of Phage-Host Interactions

Accurately predicting which bacteria a phage can infect is fundamental to applying ecogenomic principles. MoEPH (Mixture-of-Experts for Phage-Host prediction) is a novel framework that integrates transformer-based protein embeddings (from ProtBERT, ProT5) with domain-specific statistical descriptors (Amino Acid Composition, Atomic Composition) [11]. This model uses a gated fusion mechanism to dynamically combine features, achieving high accuracy (99.6% on balanced datasets) and significantly improved robustness on imbalanced data, which is common in biological studies [11]. The model's interpretability, provided by visualizing expert weights, builds trust and offers biological insight, making it suitable for clinical applications like phage therapy selection.

<100: MoEPH Model for Predicting Phage-Host Interactions

Bacteriophages (phages), the viruses that infect bacteria, are now recognized as critical drivers of microbial ecosystem dynamics. A pivotal advancement in environmental microbiology has been the discovery that the genomes of individual bacteriophages encode discernible, habitat-specific signals, termed ecogenomic signatures [1]. These signatures are based on the relative abundance of phage-encoded gene homologues in different metagenomic datasets and are diagnostic of the underlying host microbiome [1]. This application note details the patterns of these ecogenomic signatures across major habitats, focusing on the human gut and aquatic environments, and provides detailed protocols for their resolution and application in fields such as microbial source tracking (MST) and therapeutic development.

Data Presentation: Ecogenomic Signatures Across Habitats

The core evidence for habitat-specific patterns in phages comes from quantifying the representation of phage-encoded open reading frames (ORFs) in viral and whole-community metagenomes from different environments. The gut-associated phage ɸB124-14, which infects Bacteroides fragilis, serves as a key model organism [1].

Table 1: Cumulative Relative Abundance of ɸB124-14 ORFs in Viral Metagenomes

| Habitat | Mean Relative Abundance | Statistical Significance (vs. Environmental) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gut | High | Significantly greater | Notable variation between individual viromes |

| Porcine & Bovine Gut | High | Not significant (vs. Human Gut) | |

| Aquatic Environments (Marine/Freshwater) | Low | Baseline |

Table 2: Comparative Ecogenomic Profiles of Model Phages

| Phage | Natural Host / Origin | Ecogenomic Profile in Metagenomes | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ɸB124-14 | Bacteroides fragilis / Human Gut | Enriched in mammalian gut viromes [1] | Microbial Source Tracking (MST) for human faecal pollution |

| ɸSYN5 | Cyanobacteria / Marine Environment | Enriched in marine metagenomes; low in gut viromes [1] | Environmental habitat marker |

| ɸKS10 | Burkholderia cenocepacia / Plant Rhizosphere | Poorly represented; no discernible profile in datasets analysed [1] | Distantly related control phage |

Analysis of whole-community metagenomes further confirms that the ɸB124-14 ecogenomic signature can distinguish human-derived data sets from those of other origins, demonstrating its power to segregate metagenomes according to environmental source and even identify environments subject to simulated human faecal contamination [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Resolving an Ecogenomic Signature from a Bacteriophage Genome

This protocol outlines the steps to identify and validate a habitat-associated ecogenomic signature for a target phage, such as ɸB124-14 [1].

1. Define the Query and Reference Databases:

- Query Phage Genome: Obtain the complete genome sequence of the phage of interest (e.g., ɸB124-14, GenBank: NC_007804.1).

- Reference Metagenomic Databases: Curate a diverse set of metagenomic datasets from public repositories (e.g., NCBI SRA). The set should include:

- Viral metagenomes (viromes) and whole-community metagenomes.

- Habitats of interest (e.g., human gut) and control habitats (e.g., other mammalian guts, aquatic environments, soils).

2. Homology Search and Abundance Calculation:

- ORF Prediction: Predict all Open Reading Frames (ORFs) from the query phage genome using tools like

Prodigal. - Sequence Similarity Search: For each ORF, search against the processed metagenomic datasets using translated search tools (e.g.,

BLASTxorDIAMOND). Use a standardized e-value threshold (e.g., 1e-5). - Calculate Cumulative Relative Abundance: For each metagenome, calculate the cumulative relative abundance of all hits to the query phage's ORFs. This is typically normalized by the total number of sequences or total base pairs in the metagenome.

3. Data Analysis and Signature Validation:

- Statistical Comparison: Use statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test) to compare the relative abundance of the phage's ORFs between different habitat groups (e.g., human gut vs. aquatic environments).

- Discriminatory Power Assessment: Apply machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest) to evaluate if the signature can accurately predict the habitat origin of blinded metagenomic samples.

- Control Comparisons: Validate the specificity of the signature by repeating the analysis with phages from other, non-target habitats (e.g., ɸSYN5 as a marine control).

Protocol: Phage Amplification-Based Detection of Bacteria via Quantitative Imaging

This protocol leverages phage amplification for sensitive bacterial detection, utilizing fluorescence imaging as an alternative to PCR [13].

1. Sample Enrichment and Phage Infection:

- Incubate the sample (e.g., coconut water, spinach wash water) with a growth medium to enrich for the target bacteria (e.g., E. coli) for a period (e.g., 4-6 hours).

- Add a high titer of a lytic phage specific to the target bacterium (e.g., T7 phage for E. coli) to the enriched sample.

- Incubate to allow for phage infection, replication, and host cell lysis (typically 25-40 minutes for T7).

2. Phage Particle Enrichment and Staining:

- Centrifuge the lysed sample to pellet bacterial debris.

- Collect the supernatant containing the amplified phage particles.

- Stain the phage particles in the supernatant with a nucleic acid stain, such as SYBR Green I.

3. Imaging and Quantification:

- Pipette a defined volume of the stained solution onto a microscope slide and apply a coverslip.

- Image the sample using a standard fluorescence microscope.

- Perform quantitative image analysis to enumerate the fluorescent phage particles. A significant increase in phage count compared to a negative control (no host bacteria) indicates the presence of the target bacterium in the original sample. This method can detect as low as 10 CFU/ml in 8 hours, including enrichment time [13].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing a phage ecogenomic signature, from initial bioinformatic analysis to practical application.

Diagram 1: Workflow for establishing a phage ecogenomic signature.

The experimental protocol for detecting bacteria via phage amplification and imaging is summarized in the following workflow.

Diagram 2: Workflow for phage amplification-based bacterial detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Ecogenomic and Phage-Based Detection Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Model Phages | Benchmark organisms for establishing habitat-specific signatures and detection assays. | ɸB124-14 (Human gut, infects Bacteroides fragilis), T7 phage (for E. coli detection), ɸSYN5 (Marine control) [1] [13]. |

| Reference Metagenomic Datasets | Publicly available data for calculating gene homologue abundance across habitats. | Human Gut Virome, Marine Virome, Freshwater Metagenomes, Soil Metagenomes (e.g., from NCBI SRA) [1]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Software for ORF prediction, sequence similarity search, and statistical analysis. | Prodigal (ORF prediction), BLAST or DIAMOND (homology search), R packages (for statistical testing and graphing) [1]. |

| Lytic Phages | Used in detection protocols to infect and lyse specific target bacteria. | Wild-type or genetically modified phages with a broad host range within the target bacterial species [13]. |

| Nucleic Acid Stain | To fluorescently label amplified phage particles for imaging-based quantification. | SYBR Green I [13]. |

| Fluorescence Microscope | Equipment for visualizing and counting stained phage particles. | Conventional fluorescence microscope with appropriate filters [13]. |

Bacteriophages (phages), the viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant biological entities on Earth, playing a crucial role in shaping microbial community structure and function through their predatory activity and horizontal gene transfer [14] [15]. The concept of phage ecogenomic signatures refers to the unique genetic patterns encoded within phage genomes that reflect their adaptation to specific habitats and microbial communities [16]. These signatures represent a powerful framework for assessing ecosystem health and detecting perturbations, as phages co-evolve with their bacterial hosts and carry a genetic record of these interactions. Research has demonstrated that individual phage genomes encode clear habitat-related signals that can distinguish microbial ecosystems based on the relative representation of phage-encoded gene homologues in metagenomic datasets [16]. For instance, the gut-associated phage ϕB124-14 encodes an ecogenomic signature that can successfully segregate metagenomes according to environmental origin and even distinguish contaminated environmental metagenomes from uncontaminated datasets [16]. This capacity to serve as precise indicators of microbial community structure and health positions phages as invaluable tools for ecosystem monitoring, public health protection, and therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundations of Phage Ecogenomics

Ecological Principles of Phage-Host Interactions

Phages influence microbial community structure through multiple ecological mechanisms that ultimately define their utility as ecosystem indicators. The fundamental dynamic is based on density-dependent lysis of bacterial populations, similar to Lotka-Volterra predator-prey relationships, which promotes microbial diversity and resource utilization efficiency [14]. Through this regulatory function, phages prevent the dominance of any single bacterial taxon, thereby maintaining ecosystem balance and resilience.

The lifestyle strategies of phages significantly impact their indicator capabilities. Lytic phages directly kill their host cells through lysis, providing immediate feedback on the presence and abundance of specific bacterial hosts [17]. In contrast, temperate phages can integrate into bacterial chromosomes as prophages, entering a state of lysogeny that provides both a historical record of bacterial populations and a mechanism for horizontal gene transfer [14]. The prophage reservoir within a microbial community represents a genetic archive of past infections and co-evolutionary relationships [14]. Environmental conditions influence the lysis-lysogeny decision, with unfavorable conditions and low host density typically favoring lysogeny, although recent evidence suggests high host densities may also select for this strategy in complex communities [14]. This intricate relationship between phage life history strategies and microbial population dynamics forms the theoretical basis for interpreting phage ecogenomic signatures in ecosystem assessment.

Molecular Basis of Ecogenomic Signatures

The genomic composition of phages reflects their evolutionary adaptation to specific environments and hosts, creating identifiable patterns that serve as diagnostic markers. Tetranucleotide frequency profiles represent one such pattern, where the relative abundance of specific DNA four-mer sequences creates a distinctive signature that can associate phages with particular habitats or host organisms [16] [18]. Research on Proteus mirabilis bacteriophages demonstrated how tetranucleotide profiling could reveal broader host ranges and ecological affiliations, with one myophage showing a recent evolutionary association with Morganella morganii and other members of the Morganellaceae family despite being isolated using a P. mirabilis host [19].

Another crucial molecular signature lies in codon adaptation patterns, where phage genomes exhibit preferential use of certain codons that match the tRNA pools of their preferred bacterial hosts [18]. Analysis of marine Pseudoalteromonas phage H105/1 revealed that regions of the phage genome with the most host-adapted proteins also carried the strongest bacterial tetranucleotide signature, while the least host-adapted proteins displayed the strongest phage tetranucleotide signature [18]. This differential adaptation across functional modules within a single phage genome provides insights into the evolutionary history of phage proteins and their ecological relationships.

Table 1: Molecular Features Comprising Phage Ecogenomic Signatures

| Molecular Feature | Description | Ecological Significance | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetranucleotide Frequency | Relative abundance of DNA 4-mer sequences | Reflects evolutionary adaptation to specific habitats | Frequency profiling, Machine learning |

| Codon Adaptation Index | Measure of codon usage bias matching host preferences | Indicates host specificity and co-evolution | Comparative genomics |

| Auxiliary Metabolic Genes (AMGs) | Phage-encoded genes modulating host metabolism | Directly influences ecosystem biogeochemical cycling | Metagenomic sequencing, Functional annotation |

| Host Range Genetic Determinants | Genes encoding tail fibers, receptor-binding proteins | Defines breadth of susceptible bacterial hosts | Phylogenetic analysis, Protein structure prediction |

Detection and Analysis Methodologies

Computational Workflows for Signature Identification

The identification of phage ecogenomic signatures from complex microbial communities relies on integrated computational workflows that combine sequence similarity-based methods with machine learning approaches. Modern phage detection tools have evolved from early composition-based algorithms to sophisticated hybrid frameworks that integrate multiple analytical strategies [17]. The current state-of-the-art encompasses four principal approaches:

- Sequence similarity-based methods identify viral regions by homology to known phage proteins using BLAST or hidden Markov models (HMMs) from databases such as pVOGs [17]. These methods offer high accuracy when close reference sequences exist but poorly detect novel or highly divergent phages.

- K-mer-based approaches classify sequences using the frequency of short nucleotide substrings of length k (k-mers), enabling alignment-free detection of viruses with limited similarity to known phages [17].

- Machine learning and deep learning models apply random forests (RF), support vector machines (SVMs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to learn complex patterns distinguishing viral from microbial sequences [17].

- Hybrid approaches integrate similarity-based methods with homology-independent features (GC/AT skew, transcription directionality, gene density, tRNA occurrence) to achieve higher accuracy and flexibility [17].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated computational pipeline for phage ecogenomic signature analysis:

Experimental Protocol: Ecogenomic Signature Profiling for Microbial Source Tracking

Protocol 1: Detection of Habitat-Associated Phage Signatures for Water Quality Assessment

Background: This protocol describes a method for detecting phage ecogenomic signatures to identify faecal contamination in water resources, enabling microbial source tracking (MST) with higher specificity and persistence than traditional faecal indicator bacteria [16].

Materials:

- Water samples (1L each) from target aquatic environments

- 0.22µm pore-size filters for bacterial concentration

- DNase I to eliminate free bacterial DNA

- DNA extraction kits (for viral DNA)

- PCR reagents and primers for host-specific phage detection

- Metagenomic sequencing library preparation kits

Procedure:

Sample Processing and Viral Concentration

- Filter 500mL water through 0.22µm membranes to remove bacteria and particulate matter

- Concentrate viral particles from filtrate using ultrafiltration (100kDa MWCO) or iron chloride flocculation

- Treat concentrate with DNase I (1U/µL, 30min, 37°C) to degrade free bacterial DNA

Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Extract viral DNA using commercial kits with modifications for environmental samples

- Include viral internal standards (e.g., phage ϕX174) for quantification and extraction efficiency assessment

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay)

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Prepare metagenomic libraries using Illumina-compatible kits with dual index barcodes

- Perform quality control on libraries using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation

- Sequence on Illumina platform (2x150bp, minimum 10M read pairs per sample)

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Quality trim reads using Trimmomatic or FastP

- Assemble reads into contigs using metaSPAdes or MEGAHIT with multiple k-mer sizes

- Identify viral sequences using VirSorter2 and DeepVirFinder with default parameters

- Annotate phage genomes using Prokka with custom viral databases

- Calculate relative abundance of target phage signatures (e.g., ϕB124-14 homologs) using BLASTn and custom scripts

Signature Validation

- Compare signature abundance across habitats using statistical tests (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn's post-hoc)

- Construct receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to determine discriminatory power

- Validate specificity using samples from known contamination sources

Troubleshooting:

- Low viral DNA yield: Increase starting water volume or use alternative concentration methods

- High host DNA contamination: Optimize DNase treatment duration and concentration

- Poor assembly: Sequence to higher depth or use hybrid assembly approaches

Applications in Ecosystem Monitoring

Microbial Source Tracking in Water Quality Assessment

Phage ecogenomic signatures offer a powerful approach for detecting faecal contamination in water resources and identifying its sources. Traditional methods relying on faecal indicator bacteria (FIB) such as E. coli and Enterococcus spp. suffer from limitations including lack of specificity to human faeces, poor persistence in environments, and potential regrowth [16]. Phage-based approaches overcome these limitations through:

- Extended environmental persistence compared to bacterial indicators

- Human-specific associations through co-evolution with gut microbiota

- Amplification capability via propagation in host bacteria

Research has demonstrated that the gut-associated phage ϕB124-14 encodes a distinct ecogenomic signature that enables discrimination of human gut viromes from other environmental data sets [16]. Sequences with similarity to ϕB124-14 open reading frames showed significantly greater relative abundance in human gut viromes compared to environmental datasets, while non-gut phages like Cyanophage SYN5 and Burkholderia prophage KS10 displayed entirely different ecological profiles [16]. This specificity forms the basis for developing molecular assays that can distinguish human faecal contamination from animal sources in water quality monitoring.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Phage-Based vs. Traditional Microbial Source Tracking Approaches

| Parameter | Culture-Based FIB | Molecular FIB Detection | Phage Ecogenomic Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turnaround Time | 24-48 hours | 4-6 hours | 8-12 hours (sequencing-based) |

| Human Specificity | Low | Moderate | High |

| Environmental Persistence | Variable, may regrow | DNA may persist after cell death | High, longer than bacterial hosts |

| Sensitivity | 10-100 CFU/mL | 1-10 gene copies/mL | Varies with signature and sequencing depth |

| Source Discrimination | Limited | Moderate to High | High (multiple signature types) |

| Cost per Sample | $10-20 | $15-30 | $50-100 (decreasing with sequencing costs) |

Agricultural Ecosystem Health Assessment

Agricultural environments represent complex microbial ecosystems where phage ecogenomic signatures can monitor pathogen dissemination and antibiotic resistance gene transfer. A metagenomic investigation of an organic farm revealed how bacteriophages mediate antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) dissemination between bacterial populations in fecal and environmental samples [20]. The study demonstrated:

- Similarities in ARG-associated viruses across fecal and environmental components despite differences in total microbiome composition

- Caudovirales phages, particularly the Siphoviridae family, contained diverse ARG types and interacted with various bacterial hosts

- Predictive models of phage-bacterial interactions on bipartite ARG transfer networks identified key vectors for resistance dissemination

The following diagram illustrates the phage-mediated ARG transfer network in agricultural ecosystems:

Therapeutic Ecosystem Management

Phage ecogenomic signatures extend beyond environmental monitoring to therapeutic applications where they guide precise microbiome interventions. Unlike broad-spectrum antibiotics that cause widespread dysbiosis, phage therapy demonstrates remarkable specificity with minimal impact on non-target bacterial communities [21]. A controlled study comparing phage treatment to antibiotics found:

- Phage treatment caused no significant differences in bacterial density, α- and β-diversity, successional patterns, and community assembly when the host bacterium was present

- Antibiotics induced significant changes in all community characteristics investigated, including a bloom of γ-proteobacteria and a shift from selection to ecological drift dominating community assembly

- Higher amounts of bacterial host increased the contribution of stochastic community assembly but did not amplify phage treatment impacts [21]

This preservation of community structure during targeted pathogen control represents a fundamental advantage for therapeutic applications where microbiome integrity is crucial for host health, such as in human medicine, aquaculture, and agricultural disease management.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Phage Ecogenomic Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Tools | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Concentration | 0.22µm filters, 100kDa MWCO ultrafiltration units, Iron chloride flocculation reagents | Concentrate viral particles from large-volume environmental samples | Efficient recovery of diverse phage morphologies |

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy PowerWater Kit, QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit, Custom protocols with DNase treatment | Isolation of high-quality viral nucleic acids | Effective removal of contaminating bacterial DNA |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, MiSeq; Oxford Nanopore GridION, PromethION | Metagenomic sequencing of viral communities | High throughput for detection of rare signatures |

| Bioinformatic Tools | VirSorter2, DeepVirFinder, PhiSpy, metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT | Viral sequence identification and genome assembly | Machine learning approaches for novel phage detection |

| Reference Databases | pVOGs, IMG/VR, RefSeq, RVDB | Functional annotation and classification | Curated collections of viral protein families |

| Analysis Frameworks | Kaiju, Kraken2, MetaVir, iVirus | Taxonomic classification and ecological profiling | Integrated workflows for virome analysis |

Phage ecogenomic signatures represent a transformative approach for tracking microbial community structure and health across diverse ecosystems. The specificity of these genetic signatures to particular habitats and host organisms enables precise monitoring of environmental changes, contamination events, and ecosystem perturbations. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, the resolution and applicability of phage-based ecosystem assessment will expand accordingly.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on standardized signature panels for specific ecosystem types, rapid detection methodologies that bypass metagenomic sequencing, and integration of phage ecogenomic data with other molecular profiling approaches for comprehensive ecosystem assessment. The growing recognition of phages as key players in microbial ecosystems ensures that their ecogenomic signatures will play an increasingly important role in environmental monitoring, public health protection, and therapeutic interventions aimed at preserving or restoring microbial community health.

The study of bacteriophages has entered a revolutionary phase with the emergence of ecogenomics, which investigates the genetic adaptations of viruses to specific ecological niches. Within this framework, the concept of an "ecogenomic signature" has become pivotal—referring to a distinct pattern of gene homologs and genomic features that consistently associates with a particular habitat, providing a diagnostic marker for that environment [16]. The human gut microbiome represents a complex ecosystem where bacteriophages exert profound influence on microbial community structure and function. Despite their importance, the gut virome remains largely uncharted biological "dark matter," with few well-characterized reference genomes available [22] [23]. Bacteriophage ϕB124-14 infecting Bacteroides fragilis has emerged as a paradigm for understanding these habitat-associated genetic signatures. This case study explores how ϕB124-14 serves as a model system for detecting and exploiting ecogenomic signatures, with applications ranging from microbial source tracking to therapeutic development.

ϕB124-14 Characterization and Genomic Properties

Physical and Biological Characteristics

ϕB124-14 is a bacteriophage that specifically infects human gut-associated strains of Bacteroides fragilis. Physical characterization through transmission electron microscopy reveals that ϕB124-14 possesses a binary morphology with an icosahedral head (49.8 ± 3.9 nm in diameter) and a non-contractile tail (162 ± 21 nm in length, 13.6 ± 1.6 nm in diameter), classifying it within the Caudovirales order and Siphoviridae family [22] [23]. The phage produces small, clear plaques (0.7 ± 0.3 mm) when plated on its original host, Bacteroides fragilis GB-124, and demonstrates notable environmental stability, particularly regarding UV resistance [22].

Host range analysis demonstrates that ϕB124-14 exhibits remarkably narrow tropism, infecting only a subset of closely related B. fragilis strains isolated from the same municipal wastewater source, along with reference strain DSM 1396 (originally from human pleural fluid) [23]. This restricted host range underscores the high specialization of gut phages and reflects the niche adaptation that occurs at fine phylogenetic scales within the gut ecosystem [23].

Table 1: Physical and Biological Properties of ϕB124-14

| Property | Specification |

|---|---|

| Family | Siphoviridae |

| Morphology | Icosahedral head with non-contractile tail |

| Head Diameter | 49.8 ± 3.9 nm |

| Tail Dimensions | 162 ± 21 nm length, 13.6 ± 1.6 nm diameter |

| Plaque Morphology | Small (0.7 ± 0.3 mm), clear plaques |

| Host Specificity | Restricted subset of Bacteroides fragilis strains |

| Environmental Stability | High UV resistance |

Genomic Features and Unusual Functions

ϕB124-14 contains a circular double-stranded DNA genome, with comparative analyses revealing its closest relationship to ϕB40-8, another Bacteroides phage [22] [23]. At the time of its characterization, only one other complete Bacteroides phage genome was publicly available, highlighting the unexplored nature of this phage gene-space [22]. The ϕB124-14 genome encodes functions previously considered rare in viral genomes and human gut viral metagenomes, including genes that may confer advantages to either the phage or its bacterial host [22] [23].

The genomic characterization of ϕB124-14 has been extended through the identification of a novel wastewater Bacteroides fragilis bacteriophage, vBBfrS23, which shares similar ecological and genomic features with ϕB124-14 [24]. This more recently isolated phage has a genome of 48,011 bp, encoding 73 putative open reading frames, and displays stability at temperatures of 4°C and 60°C for at least one hour [24].

Table 2: Genomic Characteristics of ϕB124-14 and Related Bacteroides Phages

| Genomic Feature | ϕB124-14 | vBBfrS23 | ϕB40-8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Type | Circular dsDNA | Circularly permuted dsDNA | dsDNA |

| Genome Size | Not specified | 48,011 bp | Not specified |

| ORF Count | Not specified | 73 | Not specified |

| Relatedness | - | Similar to ϕB124-14 | Closest relative to ϕB124-14 |

| Unusual Genes | Encodes rare viral functions | Not specified | Not specified |

Ecological Profiling and Habitat Association

Human Gut-Specific Distribution

Comparative metagenomic analysis provides compelling evidence for the human gut-specific nature of ϕB124-14. Initial investigations failed to identify homologous sequences in 136 non-human gut metagenomic datasets, while demonstrating prevalence in human gut microbiomes and viromes from diverse geographic regions including Europe, America, and Japan [22] [23]. This distribution pattern suggests both human specificity and potential geographic variation in carriage [22].

Further ecological profiling using both gene-centric phylogenetic analyses and alignment-free approaches confirmed that ϕB124-14 and related Bacteroides phages populate a distinct ecological landscape within the human gut microbiome [22] [23]. This specialized niche adaptation forms the foundation of their utility as ecological markers.

Ecogenomic Signature Concept and Validation

The ecogenomic signature of ϕB124-14 manifests as the relative abundance of its gene homologs within metagenomic datasets, which is significantly enriched in human gut samples compared to other environments [16]. This signature was systematically validated by analyzing the cumulative relative abundance of sequences similar to ϕB124-14 open reading frames (ORFs) across diverse viral metagenomes from human, porcine, and bovine guts, as well as various aquatic environments [16].

The habitat-specificity of this signature becomes evident when compared to phages from other environments. While ϕB124-14 shows significant enrichment in human gut viromes, cyanophage SYN5 (from marine environments) displays the opposite pattern—greater representation in marine samples—whereas Burkholderia prophage KS10 shows no discernible habitat association [16]. This comparative approach demonstrates that individual phage can encode clear habitat-related ecogenomic signatures reflective of their underlying host microbiomes [16].

Research Protocols and Methodologies

Phage Isolation and Purification Protocol

Principle: Bacteriophages infecting Bacteroides fragilis can be isolated from wastewater samples, which contain human gut-derived phage particles.

Materials:

- Bacteroides fragilis GB-124 (host strain)

- Raw municipal wastewater sample

- Bacteriophage recovery medium (BPRM)

- Anaerobic chamber (5% CO₂, 5% H₂, 90% N₂ at 37°C)

- Filtration units (0.45 μm and 0.22 μm PES membranes)

- Amicon Ultra-15 10K centrifugal filter units

Procedure:

- Collect 100 mL raw wastewater and filter through 0.45 μm membrane

- Concentrate filtrate by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min using Amicon Ultra-15 10K filters

- Mix 1 mL concentrated filtrate with 1 mL mid-exponential growth phase B. fragilis GB-124 (OD₆₂₀ 0.3-0.4)

- Allow 5 minutes for phage adsorption

- Mix with semi-soft BPRM agar (0.35%) and pour onto BPRM agar (1.5%) base layers

- Incubate anaerobically for 18 hours at 37°C

- Pick individual plaques and resuspend in BPRM medium with fresh host culture

- Incubate for 18 hours to propagate phages

- Filter through 0.22 μm membrane to remove bacteria

- Repeat plaque purification three times to obtain pure phage stock [24]

Ecogenomic Signature Detection Protocol

Principle: The habitat-specificity of ϕB124-14 can be quantified by calculating the cumulative relative abundance of its gene homologs in metagenomic datasets.

Materials:

- Assembled metagenomes from target habitats

- ϕB124-14 reference genome sequence

- Bioinformatics tools (BLAST, sequence alignment algorithms)

- Computational resources for large-scale sequence analysis

Procedure:

- Compile metagenomic datasets from various habitats (human gut, other body sites, environmental samples)

- Annotate ϕB124-14 genome to identify all open reading frames (ORFs)

- For each metagenome, identify sequences with similarity to ϕB124-14 ORFs using tBLASTn or similar tools

- Calculate cumulative relative abundance by summing the normalized hit counts across all ϕB124-14 ORFs for each metagenome

- Compare abundance profiles across habitats using statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA)

- Validate specificity by comparing with control phages from other habitats [16]

Genome Signature-Based Phage Sequence Recovery

Principle: The phage genome signature-based recovery (PGSR) approach exploits similarities in tetranucleotide usage patterns to identify phylogenetically related phage sequences in metagenomic data.

Diagram 1: PGSR Workflow for Phage Sequence Recovery (Title: Phage Genome Signature Recovery Workflow)

Materials:

- Assembled metagenomic contigs (≥10 kb) from human gut samples

- Bacteroidales phage driver sequences

- Bioinformatics tools for tetranucleotide frequency calculation

- Functional annotation pipelines (e.g., Prokka, RAST)

- Reference databases of phage and bacterial genomes

Procedure:

- Compile large contigs (≥10 kb) from human gut metagenomes

- Calculate tetranucleotide usage profiles (TUPs) for driver phage sequences and metagenomic contigs

- Identify contigs with TUPs similar to Bacteroidales phage drivers

- Perform functional profiling of candidate contigs to categorize as phage or chromosomal

- Annotate ORFs of recovered phage fragments to verify consistent phage-related signals

- Validate by comparing relative abundance of homologous ORFs in phage genomes versus chromosomes [25]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ϕB124-14 and Gut Phage Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Host | Bacteroides fragilis GB-124 | Phage isolation & propagation | Provides susceptible host for phage replication |

| Culture Medium | Bacteriophage Recovery Medium (BPRM) | Bacterial & phage culture | Supports anaerobic growth of host and phage propagation |

| Anaerobic Chamber | 5% CO₂, 5% H₂, 90% N₂ at 37°C | All cultivation steps | Maintains anaerobic conditions essential for Bacteroides |

| Filtration Membranes | 0.45 μm & 0.22 μm PES membranes | Phage purification | Removes bacterial cells while allowing phage passage |

| Concentration Devices | Amicon Ultra-15 10K filters | Sample processing | Concentrates phage particles from large volumes |

| Reference Genomes | ϕB124-14, ϕB40-8 sequences | Bioinformatic analyses | Provides reference for comparative genomics & signature identification |

| Metagenomic Datasets | Human gut, environmental viromes | Ecological profiling | Enables habitat association studies |

Applications and Technological Implications

Microbial Source Tracking (MST) Tools

The strong human gut-specific ecogenomic signature of ϕB124-14 enables its application in microbial source tracking (MST) for water quality assessment [16]. Phage-based MST offers significant advantages over traditional fecal indicator bacteria, including longer environmental persistence, greater abundance than host bacteria, and human-specific signals that distinguish contamination sources [16]. The ϕB124-14 ecogenomic signature can successfully discriminate human gut viromes from other datasets and identify 'contaminated' environmental metagenomes in simulated fecal pollution scenarios [16].

The development of culture-independent detection methods based on ϕB124-14's genetic signature provides a pathway toward rapid, sensitive water quality monitoring that could potentially deliver results in near real-time [16]. This application addresses critical public health needs for managing water resources and safeguarding against fecal contamination.

Therapeutic Exploration and Biotechnological Applications

While ϕB124-14 itself is not currently deployed therapeutically, its characterization contributes to the growing foundation for phage therapy applications. Bacteriophages in general are gaining attention as promising alternatives to antibiotics for multidrug-resistant infections, with the ability to target specific pathogens, disrupt biofilms, and reach intracellular pathogens [26]. The detailed understanding of narrow host-range phages like ϕB124-14 informs therapeutic strategies for targeting specific pathogenic strains without disrupting commensal microbiota.

Recent regulatory advances, including the EMA's "Guideline on quality aspects of phage therapy medicinal products," establish frameworks for characterizing therapeutic phages, requiring taxonomic classification, host range determination, genome sequencing, and detailed characterization of phage seed lots [27]. The methodologies applied to ϕB124-14 provide a template for such characterization.

Visualizing Ecogenomic Signature Analysis

Diagram 2: Ecogenomic Signature Analysis Pipeline (Title: Ecogenomic Signature Analysis Workflow)

ϕB124-14 exemplifies how individual bacteriophages can encode distinct habitat-associated genetic signatures that reflect their co-evolution with host bacteria and adaptation to specific ecosystems. The ecogenomic signature of ϕB124-14 provides a powerful tool for detecting human fecal contamination in environmental waters, with potential for development into rapid, culture-independent microbial source tracking methods [16]. Furthermore, the genomic characterization of ϕB124-14 and related Bacteroides phages illuminates a portion of the biological "dark matter" within the human gut virome, revealing a population of potentially gut-specific Bacteroidales-like phages that are poorly represented in virus-like particle-derived metagenomes [25].

Future research directions should focus on expanding the catalog of well-characterized gut phages, refining ecogenomic signature detection methodologies, and translating these findings into practical applications for water quality monitoring and therapeutic development. As sequencing technologies advance and regulatory frameworks mature [27] [26], the principles demonstrated through ϕB124-14 will undoubtedly find broader applications in managing microbial ecosystems and combating antibiotic-resistant infections.

From Sequence to Solution: Detecting and Applying Phage Ecogenomic Signatures

Ecogenomic signatures are habitat-specific genetic patterns encoded within phage genomes, serving as powerful indicators of their microbial ecosystem origins. The discovery that individual bacteriophages encode discernible habitat-associated signals has opened new frontiers in microbial source tracking (MST) and therapeutic development [1]. This application note details standardized protocols for extracting these signatures from complex metagenomic data, enabling researchers to classify phage origins and identify novel therapeutic candidates. By integrating computational mining with experimental validation, we provide a comprehensive framework for leveraging phage ecogenomics in drug development and diagnostic applications.

Quantitative Foundations of Phage Ecogenomics

The Oral Phage Database (OPD) exemplifies the scale of modern phage ecogenomics, comprising 189,859 representative phage genomes from 5,427 metagenomic samples across diverse populations [28]. This resource reveals that oral phages demonstrate remarkable genetic diversity with a median genome size of 27.61 kbp, including 3,416 huge phages (>200 kbp). Notably, over 90% of oral phages represent previously unknown genetic diversity, encoding an enormous variety of "dark proteins" with uncharacterized functions [28].

Table 1: Quantitative Profile of Oral Phage Database (OPD)

| Parameter | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total metagenomic samples | 5,427 | Cross-population coverage |

| Representative phage genomes | 189,859 | Extensive sequence diversity |

| Median genome size | 27.61 kbp | Benchmark for oral phages |

| Huge phages (>200 kbp) | 3,416 | Expanded complexity |

| Complete/high-quality genomes | 4,709 (2.5%) | High-quality reference set |

| Medium-quality genomes | 53,432 (28.1%) | Usable draft genomes |

| Non-singleton viral clusters | 1,915 | Taxonomic grouping |

| Sub viral clusters (subVCs) | 9,983 | Strain-level diversity |

Comparative analysis reveals distinct ecological partitioning between body sites. The OPD exhibits minimal overlap with gut virome databases (GVD, GPD), confirming specialized phage communities adapt to specific microbial habitats [28]. This ecological specialization forms the foundation for reliable ecogenomic signature identification.

Experimental Workflow for Signature Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for phage ecogenomic signature discovery:

Core Protocol: Identifying Phage Ecogenomic Signatures

Computational Protocol: Ecogenomic Signature Extraction

Objective: Identify habitat-specific genetic signatures in phage genomes from metagenomic data.

Materials:

- High-quality metagenomic sequencing data from target habitats

- High-performance computing cluster with ≥64GB RAM

- Reference databases: OPD, GVD, IMG/VR [28] [29]

Methodology:

Viral Sequence Recovery

Database Construction & Clustering

- Assess genome completeness using CheckV (>50% completeness for draft genomes) [28]

- Cluster viral genomes using vConTACT2 based on shared protein clusters

- Generate viral clusters (VCs) and sub-clusters (subVCs) for taxonomic analysis

Ecogenomic Signature Identification

- Annotate representative genomes using geNomad with ICTV MSL39 database [28]

- Calculate cumulative relative abundance of phage-encoded ORFs across habitats

- Perform comparative analysis against reference phage (ɸB124-14 for gut, ɸSYN5 for marine) [1]

- Identify signature genes significantly enriched in target habitat (p<0.05, fold-change>2)

Machine Learning Enhancement

- Predict protein-protein interactions between phage and bacterial hosts

- Train random forest classifiers using PPI features and experimental host-range data [30]

- Validate model accuracy through cross-validation (>80% accuracy benchmark)

Deliverables: Habitat-specific phage signatures, classified phage genomes, trained prediction models.

Experimental Protocol: Signature Validation & Host Range Determination

Objective: Validate computational predictions of phage-host interactions through experimental assays.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains from target species (e.g., Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli)

- Phage isolates or synthetic phage variants

- Luria-Bertani broth and agar

- 96-well microtiter plates

- Microplate reader with temperature control

Methodology:

Quantitative Host Range Assay

- Grow bacterial cultures to ~1×10^8 CFU/mL in appropriate media

- Dilute cultures to 1×10^6 CFU/mL and mix with bacteriophage at 2×10^8 PFU/mL (MOI=20)

- Incubate in microtiter plate at 37°C with continuous agitation

- Monitor OD600 every 10 minutes for 6 hours

- Calculate growth inhibition as percentage reduction in area under curve versus untreated control

- Classify as "sensitive" (>15% inhibition) or "resistant" (<15% inhibition) [30]

Plaque Assay Validation

- Mix 100μL overnight bacterial culture with 6mL 0.45% soft agar

- Pour over 1.5% agar plates and allow to solidify

- Spot 10μL of each bacteriophage (1×10^8 PFU/mL) on bacterial lawns

- Incubate overnight at 37°C

- Score lytic activity by presence of clearance zones or distinct plaques

Therapeutic Efficacy Assessment

- Select phage variants with validated host range against target pathogens

- Test efficacy under physiologically relevant conditions (pH, temperature, media)

- For E. coli O121 targeting: use Meta-SIFT engineered T7 phage variants [29]

Deliverables: Experimentally validated phage-host interaction network, therapeutic candidate prioritization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Phage Ecogenomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Analysis Tools | VirSorter2, VirFinder, CheckV | Viral sequence identification, quality assessment [28] [17] |

| Classification & Clustering | vConTACT2, geNomad | Taxonomic classification, viral cluster generation [28] |

| Metagenomic Mining | Meta-SIFT | Functionally relevant motif discovery [29] |

| Reference Databases | OPD, GVD, IMG/VR, pVOGs | Reference sequences, functional annotation [28] [17] [29] |

| Host Range Assay | 96-well microtiter plates, LB media | High-throughput interaction validation [30] |

| PCR Reagents | PCR Biosystems reagents | Target gene amplification, diagnostic development [31] |

Advanced Applications in Therapeutic Development

Meta-SIFT: Metagenomic Mining for Phage Engineering

The Meta-SIFT (Metagenomic Sequence Informed Functional Training) platform enables mining of functionally validated sequence motifs from metagenomic databases to engineer phage host range [29]. This method uses deep mutational scanning (DMS) data to create weighted substitution profiles, then searches metagenomic databases for matching motifs in structural proteins. When applied to T7 phage, Meta-SIFT identified 15,561 6mer motifs from 61,017 metagenomic structural proteins, enabling engineering of variants with novel host specificity, including activity against foodborne pathogen E. coli O121 where wild-type phage lacked efficacy [29].

Machine Learning for Strain-Specific Predictions

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) data coupled with experimental host-range datasets enables training of machine learning models with 78-94% accuracy for predicting strain-specific phage-host interactions [30]. This approach overcomes limitations of taxonomy-based prediction by incorporating molecular interaction data, providing more reliable therapeutic candidate selection.

Ecogenomic signatures in bacteriophage genomes represent a powerful tool for understanding microbial ecosystems and developing targeted therapeutic interventions. The integrated computational and experimental framework presented here enables researchers to reliably extract these signatures from complex metagenomic data and validate their functional significance. As phage ecogenomics continues to evolve, these approaches will play an increasingly vital role in combating antimicrobial resistance and developing precise microbial community management strategies.

Holo-transcriptomics: Capturing Transcriptionally Active Phage-Host Interactions

The study of bacteriophages has entered a revolutionary phase with the emergence of holo-transcriptomics, a powerful approach that captures the complete transcriptome of an ecosystem by simultaneously sequencing host, bacterial, and phage RNAs. This technique provides unprecedented insights into the dynamic interactions between phages and their bacterial hosts, moving beyond static genomic information to reveal the functionally active components of these relationships. When framed within the context of ecogenomic signatures—the habitat-specific genetic patterns embedded in phage genomes—holo-transcriptomics enables researchers to identify not only which phages are present in a particular environment, but which are transcriptionally active and potentially influencing microbial community structure and function [10] [1].

The significance of this approach lies in its ability to bridge the gap between genomic potential and functional activity. While genomic studies have revealed that bacteriophage genomes encode discernible habitat-associated signals, holo-transcriptomics illuminates how these genetic signatures are expressed in different environmental contexts [1] [32]. This is particularly valuable for understanding phage therapy applications, monitoring antimicrobial resistance (AMR) dynamics, and investigating how phages modulate microbiomes in various disease states [10]. By capturing the transcriptional activity of all biological entities within a sample, researchers can now explore the intricate defense and counter-defense interactions that occur during phage infection, providing essential insights for advancing bacterial control in clinical settings [10] [33].

Theoretical Foundation: From Genomic Signatures to Transcriptional Activity

Ecogenomic Signatures in Phage Genomes

The concept of ecogenomic signatures is fundamental to understanding phage ecology. Research has demonstrated that individual phage genomes encode habitat-specific signals based on the relative representation of their gene homologues in metagenomic datasets [1]. For example, the gut-associated phage ɸB124-14 carries a distinct ecological signature that enables segregation of metagenomes according to their environmental origin, effectively distinguishing human fecal contamination in environmental samples [1] [32]. These signatures arise from the co-evolution and adaptation of phage and host to specific environments, creating a genomic record of their ecological relationships [1].

The power of these ecogenomic signatures lies in their discriminatory capability. Studies have shown that phages from different habitats—human gut, marine environments, soil ecosystems—maintain distinct genomic profiles that reflect their ecological origins [1] [34]. For instance, while the gut-associated ɸB124-14 shows significant enrichment in mammalian gut-derived viromes, marine cyanophage SYN5 displays greater representation in marine environmental datasets [1]. This habitat-specific signal provides a foundation for investigating how environmental conditions influence phage gene expression and host interactions.

The Holo-Transcriptomic Advantage

Holo-transcriptomics advances beyond ecogenomic profiling by capturing the functionally active dimension of phage-host relationships. Where genomic approaches identify which phages are present, holo-transcriptomics reveals which are actively transcribing genes, engaging with hosts, and potentially influencing microbial community dynamics [10]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying transcriptionally active microbes (TAMs) and their phage predators, offering insights into the functional state of a microbial ecosystem [10].

The application of holo-transcriptomics enables researchers to:

- Identify novel viral transcripts and phage-encoded small regulatory RNAs [33]

- Characterize transcription unit architectures and phage-specific regulatory elements [33]

- Detect active antimicrobial resistance genes during phage infection [10]

- Uncover phage-mediated modulation of host metabolic pathways [35]

- Profile temporal changes in bacterial and viral gene expression during infection [36]

By integrating these transcriptional insights with established ecogenomic principles, researchers can develop a more comprehensive understanding of how phage-host interactions shape microbial communities across different habitats.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Holo-Transcriptomic Sequencing Framework

The successful application of holo-transcriptomics to phage-host interactions requires careful experimental design and execution. The following workflow outlines the key steps in a standard holo-transcriptomic protocol:

Table 1: Key Steps in Holo-Transcriptomic Workflow for Phage-Host Studies

| Step | Procedure | Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection & Stabilization | Immediate stabilization of RNA using reagents like RNAlater | Preserves in situ transcriptional profiles | Critical for capturing transient infection events; sample volume must be sufficient for downstream analyses [35] |

| RNA Extraction | Total RNA isolation using commercial kits with modifications for viral RNA | Captures host, bacterial, and phage transcripts | Must optimize for diverse RNA species; include DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination [36] |

| Host RNA Depletion | Selective removal of ribosomal and eukaryotic host RNAs | Enriches for microbial and viral transcripts | Significantly improves detection of low-abundance phage transcripts; can use probe-based hybridization [10] |

| Library Preparation | Construction of strand-specific RNA-seq libraries | Maintains transcriptional directionality | Essential for identifying antisense transcripts and precise mapping of transcription start sites [33] |

| Sequencing | High-throughput sequencing on Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore platforms | Generates comprehensive transcriptomic data | Long-read technologies (ONT, PacBio) facilitate full-length transcript assembly and operon mapping [10] [33] |

| Bioinformatic Analysis | Multi-step computational pipeline for quality control, assembly, and annotation | Extracts biological insights from raw data | Requires specialized databases (PhageScope, IMG/VR) and both reference-based and de novo approaches [10] |

Specialized Methodologies for Phage Transcriptomics

Several advanced methodologies have been developed specifically to address the unique challenges of studying phage transcriptomes:

Differential RNA-seq (dRNA-seq): This technique employs terminator exonuclease treatment to degrade processed transcripts, thereby enriching for primary transcripts and enabling precise mapping of transcription start sites (TSSs) and their associated promoters [33]. The application of dRNA-seq to jumbo phage ΦKZ infection in Pseudomonas aeruginosa revealed distinct promoter motifs and phage transcription unit architectures, uncovering previously unknown regulatory elements [33].

Term-seq: This approach specifically sequences exposed 3´-transcript termini, enabling high-throughput discovery of transcription termination events [33]. When combined with TSS mapping, this provides a comprehensive view of transcript boundaries and operon structures.

Long-read transcriptome sequencing: Methodologies utilizing Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) or PacBio sequencing allow for full-length transcript characterization without assembly, greatly facilitating the annotation of complex transcriptional architectures [33]. The recent application of ONT-cappable-seq to phages LUZ7 and LUZ100 has provided high-resolution maps of transcriptional regulatory elements in both the virus and its host from a single experiment [33].

Temporal transcriptomic profiling: Time-series sampling during phage infection reveals the dynamic sequence of transcriptional events. For example, a study tracking E. coli infection with phage vBEcoK1B4 identified precise temporal regulation of both host and phage genes, showing how the phage sequentially redirects host resources while countering bacterial defense mechanisms [36].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for holo-transcriptomic analysis of phage-host interactions:

Key Research Applications and Findings

Characterizing Phage-Host Transcriptional Dynamics

Holo-transcriptomic approaches have revealed intricate transcriptional interplay between phages and their hosts. A study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infected with lytic phage PaP1 demonstrated that 7.1% (399/5655) of host genes were differentially expressed, with the majority (354 genes) being downregulated during late infection [35]. These suppressed genes were predominantly involved in amino acid and energy metabolism pathways, indicating strategic reprogramming of host resources to support phage replication [35].

Complementary metabolomic profiling of the same system revealed significant alterations in metabolite levels, including increased thymidine (supported by phage-encoded thymidylate synthase expression) and drastic reduction of intracellular betaine with corresponding choline accumulation [35]. These findings illustrate how phage-directed host gene expression, combined with phage-encoded auxiliary metabolic genes, collaboratively reprograms host metabolism to support viral replication.

Ecogenomic Applications in Microbial Source Tracking