Decoding Environmental Contamination: Phage Ecogenomic Signatures as Next-Generation Tools for Microbial Source Tracking

This article explores the emerging paradigm of using bacteriophage (phage) ecogenomic signatures for high-resolution microbial source tracking (MST).

Decoding Environmental Contamination: Phage Ecogenomic Signatures as Next-Generation Tools for Microbial Source Tracking

Abstract

This article explores the emerging paradigm of using bacteriophage (phage) ecogenomic signatures for high-resolution microbial source tracking (MST). As traditional fecal indicator bacteria face limitations in specificity and persistence, phage-encoded ecological signals offer a powerful, culture-independent alternative. We detail the foundational principles of habitat-associated signals embedded in phage genomes and review methodologies for their extraction from viral and whole-community metagenomes. The content covers bioinformatic pipelines for signature identification, addresses challenges in specificity and data interpretation, and provides a comparative analysis with existing MST methods. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current evidence and future directions, highlighting the potential of phage ecogenomics to revolutionize water quality monitoring and public health risk assessment.

The Signal in the Virus: Uncovering Habitat-Specific Patterns in Phage Genomes

Phage ecogenomic signatures represent a powerful conceptual and analytical framework for understanding virus-host-environment relationships through patterns embedded in viral genomic sequences. These signatures are defined as habitat-specific signals encoded within bacteriophage genomes, manifesting through both relative representation of gene homologues in metagenomic data sets and distinct nucleotide usage patterns that reflect co-evolution with bacterial hosts [1]. This paradigm has emerged from the fundamental observation that phages infecting the same or related host species often share similarities in global nucleotide usage patterns, creating a identifiable "genome signature" [2]. This signature persists despite the mosaic nature of phage genomes and provides a homology-free method for classifying phages and predicting host relationships when conventional approaches fail.

The application of ecogenomic signatures is particularly valuable in microbial source tracking (MST), where identifying the origin of fecal contamination in environmental waters represents a critical public health challenge [1] [3]. Traditional methods relying on fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) suffer from poor host specificity, environmental replication, and inability to distinguish human from non-human pollution sources [3] [4]. Phage-based signatures overcome these limitations by targeting viruses that exhibit high host specificity, greater environmental persistence than their bacterial hosts, and distinct habitat associations [1]. Furthermore, because phages co-evolve with and adapt to specific host microbiomes, they encode discernible signals diagnostic of underlying microbial ecosystems, making them ideal candidates for developing refined MST tools [1] [2].

Analytical Foundations: Core Methodological Principles

Genome Signature Analysis Using Oligonucleotide Patterns

The foundation of ecogenomic signature analysis rests on quantifying and comparing oligonucleotide usage patterns across phage genomes. This approach exploits the phenomenon that DNA sequences from related organisms often exhibit similar biases in their oligonucleotide (k-mer) composition, creating a quantifiable "genomic signature" that is taxonomically informative [5] [2].

The methodological workflow involves:

- Sequence preprocessing: Extraction of viral sequences from whole-community metagenomes or virus-like particle (VLP) enriched samples

- Oligonucleotide frequency calculation: Determination of normalized frequencies of k-mers (typically di-, tri-, or tetranucleotides) across target sequences

- Distance metric computation: Calculation of signature dissimilarity between phage and potential host genomes

- Statistical validation: Assessment of signature significance through comparison with appropriate control sequences

The distance between phage and host genomic signatures can be calculated using the formula:

[ D = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \left| \frac{f{\text{phage}}(i) - f{\text{host}}(i)}{f{\text{host}}(i)} \right| ]

where ( f(i) ) represents the normalized frequency of the i-th oligonucleotide, and N is the total number of possible oligonucleotides for a given k-mer length [5].

This signature-based approach successfully differentiates phage growth lifestyles, with temperate phages typically showing significantly smaller genomic signature distances from their hosts compared to lytic phages [5]. For example, analysis of Escherichia coli Caudoviridae revealed that lambda-like temperate phages formed a distinct cluster characterized by short signature distances from the E. coli genome, while lytic phages like the T7 super-group exhibited greater distances [5].

Functional Profiling of Signature-Associated Sequences

Complementary to nucleotide usage patterns, functional annotation of signature-identified sequences provides critical biological validation and insight into potential mechanisms underlying habitat adaptation. The functional profiling workflow encompasses:

- Open reading frame (ORF) prediction from signature-identified sequences

- Homology-based annotation using databases of phage and bacterial proteins

- Quantification of relative abundance of phage-encoded gene homologues across different habitat types

- Statistical comparison of functional profiles between habitats

This approach demonstrated its power in identifying gut-specific Bacteroidales-like phage sequences, which were enriched in human gut metagenomes compared to other body sites or environmental habitats [2]. Importantly, functional profiling confirmed these sequences encoded consistent phage-related proteins across their entire length, with significantly higher representation in phage genomes compared to chromosomal sequences, validating their viral origin [2].

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods for Phage Ecogenomic Signature Resolution

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Analysis | Tetranucleotide Usage Profiling (TUP) | Host-range prediction & phage classification | Homology-free; works with novel sequences |

| Distance Metrics | Genomic Signature Distance | Lifestyle prediction (lytic vs temperate) | Quantifies phage-host co-evolution |

| Functional Analysis | Relative Abundance Scoring | Habitat association assessment | Validates biological significance |

| Sequence Recovery | Phage Genome Signature-based Recovery (PGSR) | Targeted phage sequence extraction from metagenomes | Accesses subliminal, phylogenetically-targeted phages |

Experimental Protocols: Resolving Habitat-Associated Signatures

Protocol 1: Ecogenomic Signature Profiling Using Metagenomic Data

This protocol outlines the methodology for evaluating habitat-associated ecogenomic signatures using viral and whole-community metagenomes, as demonstrated in the analysis of ϕB124-14, a human gut-associated Bacteroides phage [1].

Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect viral metagenomes from target habitats (human gut, porcine gut, bovine gut, aquatic environments)

- Process samples through VLP purification, nucleic acid extraction, and sequencing

- Obtain whole-community metagenomes from same habitats for comparison

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Reference phage selection: Identify target phage genomes with known habitat associations (e.g., ϕB124-14 for human gut, ϕSYN5 for marine environments)

- ORF database construction: Translate all open reading frames from reference phage genomes

- Metagenome screening: Identify sequences generating valid hits (e-value < 0.001) to reference ORFs in each metagenome

- Abundance quantification: Calculate cumulative relative abundance of sequences similar to reference phage ORFs in each habitat

- Statistical comparison: Perform pairwise comparisons of relative abundance between habitats using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test)

Validation and Controls:

- Include control phages from divergent habitats (e.g., marine cyanophage SYN5, rhizosphere-associated KS10)

- Verify that control phages show distinct ecological profiles (e.g., ϕSYN5 enrichment in marine environments)

- Confirm that habitat associations are not general properties of all phages in a dataset

This protocol successfully demonstrated that ϕB124-14 encoded a clear gut-associated ecogenomic signature, with significantly greater representation in human gut viromes compared to environmental datasets [1]. The signature showed sufficient discriminatory power to distinguish "contaminated" environmental metagenomes (subject to simulated human fecal pollution) from uncontaminated datasets [1] [6].

Protocol 2: Phage Genome Signature-Based Recovery (PGSR) from Metagenomes

The PGSR approach enables targeted extraction of subliminal phage sequences from conventional whole-community metagenomes based on tetranucleotide usage patterns [2].

Driver Sequence Selection:

- Select known phage sequences with desired host range (e.g., Bacteroidales phage for human gut virome)

- Curate high-quality reference genomes for signature derivation

Metagenome Interrogation:

- Preprocess metagenomic contigs: Filter for large contigs (≥10 kb) from target metagenomes

- Calculate tetranucleotide profiles: Generate tetranucleotide usage patterns for all contigs and driver phages

- Similarity assessment: Identify metagenomic fragments with TUPs similar to driver sequences using distance metrics

- Functional binning: Annotate recovered sequences and categorize as phage or non-phage based on functional profiles

Fidelity Validation:

- Annotate randomly selected PGSR sequences and evaluate ORFs for phage association

- Compare gene distribution between PGSR phage and PGSR non-phage sequences

- Confirm high representation of PGSR phage genes in phage databases versus chromosomal sequences

Application of this protocol to 139 human gut metagenomes recovered 85 phage fragments (20.83% of signature-positive sequences) ranging from 10-63.7 kb, including 16 nearly complete phage genomes [2]. Comparative analysis showed the PGSR approach outperformed conventional alignment-driven methods, recovering phage sequences that blast-based searches failed to detect [2].

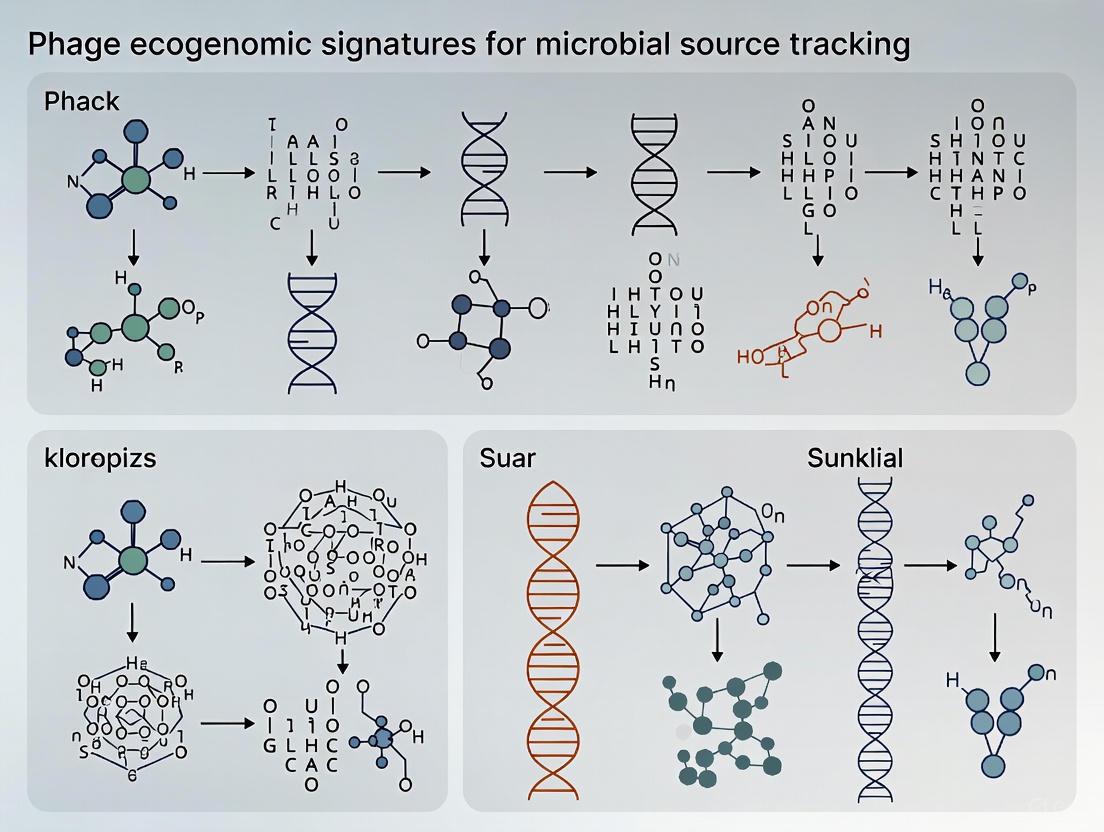

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for resolving phage ecogenomic signatures from metagenomic data, encompassing sample preparation, computational signature analysis, and biological validation stages.

Quantitative Data Synthesis: Signature Performance Across Habitats

Habitat Discrimination Performance

The discriminatory power of phage ecogenomic signatures has been quantitatively demonstrated across multiple studies and phage types. Analysis of ϕB124-14 showed significantly greater mean relative abundance of encoded ORFs in human gut viromes compared to environmental datasets [1]. Meanwhile, control phages from non-gut habitats exhibited distinct patterns, with cyanophage SYN5 showing significantly greater representation in marine environments [1].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Selected Phage-Based MST Markers in Field Studies

| Marker Phage/Host System | Sensitivity in Human Sewage | Specificity Against Non-Human Sources | Key Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides fragilis GB-124 | 71-93% (seasonal variation) | 95% (absent in 95% animal samples) | Low-cost MST in resource-limited settings | [3] [4] |

| Somatic coliphages (WG-5) | 100% | 10-60% (present in multiple species) | General fecal indicator | [3] [4] |

| crAss-like phage (Genus VI) | 98.3% (human fecal samples) | High (theoretical, requires validation) | Broad-spectrum human MST | [7] |

| ϕB124-14 (in silico) | Significantly enriched in human gut metagenomes | Discriminates human vs. non-human gut viromes | Metagenomic MST | [1] |

Signature Distance Correlates with Phage Lifestyle

Quantitative analysis of genomic signature distances between phages and their hosts reveals systematic patterns correlating with phage lifestyle. Examination of 46 E. coli Caudoviridae genomes demonstrated that temperate phages (e.g., lambda-like phages) cluster with significantly shorter signature distances from the host genome compared to lytic phages (e.g., T7 super-group) [5].

Figure 2: Relationship between phage lifestyle, genomic signature distance from host, and implications for microbial source tracking applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ecogenomic Signature Research

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Application/Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Phages | ϕB124-14 (Bacteroides fragilis phage) | Human gut signature model | Infects restricted set of human-associated B. fragilis [1] |

| Reference Phages | Cyanophage SYN5 | Marine environment signature control | Represents non-gut habitat signatures [1] |

| Bacterial Hosts | Bacteroides fragilis GB-124 | Phage propagation for MST assays | Low-cost fecal monitoring in field settings [3] [4] |

| Bacterial Hosts | E. coli WG-5 | Somatic coliphage detection | General fecal indicator, non-source specific [3] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Tetranucleotide Usage Profiling | Genome signature analysis | K-mer based habitat association [1] [2] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Phage Genome Signature-based Recovery | Targeted sequence extraction | Accesses subliminal phage sequences [2] |

| Analytical Databases | Custom phage ORF databases | Functional profiling & homology assessment | Enables relative abundance calculations [1] |

| Laboratory Equipment | Virus-like particle purification systems | Viral metagenome preparation | Enriches for free phage particles [2] |

Discussion: Implementation Considerations and Future Directions

The resolution of habitat-associated ecogenomic signatures in phage genomes represents a paradigm shift in microbial source tracking, moving beyond indicator organisms to exploit co-evolutionary signals embedded in viral genomes. The consistent demonstration that individual phages encode discernible habitat-specific signatures supports their utility as next-generation MST tools with superior discriminatory power [1] [2].

Critical implementation considerations include:

Geographic and Temporal Stability: Field studies demonstrate that phage-based markers like GB-124 exhibit seasonal variations in detection levels (71% in dry season vs. 93% in rainy season) [3]. This temporal dynamics must be accounted for in monitoring programs and suggests that complementary marker systems may be necessary for robust year-round detection.

Technical Accessibility: While computational approaches like PGSR offer powerful solutions for analyzing existing metagenomic datasets [2], low-cost phage cultivation methods (e.g., GB-124 based assays) provide accessible alternatives for resource-limited settings where molecular capabilities are constrained [3] [4]. The 18-24 hour turnaround time for phage cultivation-based methods represents a significant advantage over culture-independent approaches requiring sophisticated instrumentation.

Marker Validation Frameworks: Successful implementation requires rigorous specificity testing against diverse non-target hosts. For example, GB-124 phages were absent in 95% of animal samples tested, with detection limited to three porcine samples [3]. This level of comprehensive validation is essential before deployment in monitoring programs.

Future developments will likely focus on expanding phage marker panels to cover diverse pollution scenarios, integrating computational and cultivation-based approaches for verification, and establishing standardized protocols for cross-study comparisons. The emergence of crAss-like phages as human-specific markers [7] further expands the toolkit available for MST applications. As sequencing technologies become more accessible and analytical methods more refined, phage ecogenomic signatures are poised to become central elements in water quality management and public health protection strategies worldwide.

Bacteriophages, the most abundant biological entities on Earth, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to sense and record environmental conditions within their genomes. This whitepaper details the core principles by which phages acquire and retain diagnostic host and habitat signals, forming the foundation for their use in microbial source tracking. We examine molecular acquisition pathways, genomic retention strategies, and experimental methodologies for deciphering these ecogenomic signatures. The precise molecular interactions between phages and their hosts create a record of environmental conditions, enabling researchers to reconstruct microbial interactions and habitat influences through phage genomic analysis.

Bacteriophages (phages) serve as natural biological sensors that continuously monitor and respond to their environments. Through co-evolution with bacterial hosts, phages have developed exquisite mechanisms for acquiring information about host physiology, population density, and environmental conditions. These signals become embedded within phage genomes through specific molecular interactions, mutation patterns, and gene content adaptations. The resulting ecogenomic signatures provide a retrievable record of environmental conditions and host interactions that can be exploited for microbial source tracking and diagnostics. Phages are particularly valuable for this purpose due to their abundance, diversity, and host-specificity, with an estimated global population of 10³¹ particles that inhabit every niche where bacteria exist [8] [9].

The fundamental premise of phage-based microbial source tracking rests on two core principles: signal acquisition (how phages detect and respond to environmental and host cues) and signal retention (how these cues leave durable, detectable signatures in phage genomes or phenotypic behaviors). Understanding these mechanisms provides researchers with a powerful framework for developing precise tracking tools that can identify contamination sources, monitor microbial community dynamics, and track pathogen movements across diverse ecosystems.

Molecular Mechanisms of Signal Acquisition

Phages employ sophisticated molecular machinery to detect and respond to host and environmental signals, fine-tuning their infection strategies to optimize survival. These acquisition mechanisms represent the frontline of phage-environment interaction.

Communication-Based Sensing Systems

The Arbitrium System represents a paradigm-shifting discovery in phage-host communication. Initially identified in Bacillus-infecting phages, this peptide-based signaling mechanism enables phages to coordinate lysis-lysogeny decisions at the population level [10]. The system operates through a precise molecular pathway:

- AimP Peptide Production: During infection, phages transcribe and translate the aimP gene, producing a precursor peptide that is processed into a mature 6-amino acid peptide by host proteases.

- Signal Secretion and Accumulation: The mature AimP peptide is secreted into the extracellular environment via host secretion systems, where its concentration directly reflects the density of infected hosts.

- AimR Receptor Detection: Under low host density conditions, the AimR transcription factor maintains an "open" conformation that activates transcription of the aimX regulatory element.

- Conformational Switching: At high host densities, accumulated AimP binds to the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain of AimR, inducing a "closed" conformation that prevents DNA binding and represses aimX transcription.

- Lysis-Lysogeny Decision: The aimX output determines phage fate, promoting lytic genes during host scarcity and lysogenic integration during host abundance [10].

This sophisticated quorum-sensing analog allows phages to optimize their replication strategy based on host availability, avoiding premature host depletion while maximizing propagation opportunities.

Cross-Talk with Bacterial Quorum Sensing: Phages also eavesdrop on bacterial communication systems. In Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, phage receptors are directly regulated by bacterial LuxR-family transcription factors that respond to exogenous acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signals. Specifically, PsaR1 and PsaR3 detect environmental AHLs and repress expression of the outer membrane protein OmpV, which serves as a phage receptor. This regulation creates a defensive mechanism where bacteria can reduce phage susceptibility in response to population density cues, while simultaneously providing phages with information about bacterial communicative activity [11].

Surface Receptor Recognition and Adaptation

Receptor Binding Specificity: Phage infection initiates with precise recognition of host surface receptors, including outer membrane proteins, lipopolysaccharides, flagella, and pili. This interaction represents the primary host-sensing event and determines infection specificity. For example, phage KBC54 infecting Pseudomonas syringae targets the OmpV outer membrane protein, with bacterial quorum-sensing systems modulating this receptor availability in response to environmental AHL signals [11].

Tail Fiber Evolution: Phage tail proteins, particularly tail fibers and spike proteins, exhibit rapid evolutionary adaptation to host surface determinants. These specialized structures recognize specific bacterial receptors with exquisite molecular precision, serving as the most important checkpoint in the infection process and defining phage host range. The genetic regions encoding these proteins often display heightened mutation rates and modular architecture, enabling rapid host range adaptation [11].

Environmental Stress Sensing

Phages directly sense and respond to environmental stressors through integration of host stress responses. When bacteria experience DNA damage (e.g., from UV exposure or chemicals), they activate the SOS response, which simultaneously triggers prophage induction from lysogenic states. This mechanism allows phages to escape compromised hosts while recording exposure to environmental stressors through induction frequency [12]. Additional environmental sensing includes:

- Nutrient Availability: Phages monitor host metabolic status through intracellular nucleotide pools and energy currency availability, influencing lysis-lysogeny decisions.

- Oxidative Stress: Bacterial oxidative stress responses can induce phage activation, linking phage behavior to environmental redox conditions.

- Temperature Sensing: Through host heat-shock protein regulation, phages indirectly sense thermal fluctuations that impact infection parameters.

Table 1: Molecular Mechanisms of Signal Acquisition in Bacteriophages

| Acquisition Mechanism | Molecular Components | Information Acquired | Phage Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbitrium Communication | AimP peptide, AimR receptor, AimX regulator | Host population density | Lysis-lysogeny decision |

| Bacterial Quorum Sensing Eavesdropping | LuxR-type receptors, AHL signals | Bacterial population density & communication | Receptor expression modulation |

| Surface Receptor Recognition | Tail fibers, spike proteins, OMP receptors | Host identity & availability | Infection initiation & host range determination |

| Stress Response Integration | SOS response regulators, RecA, CI repressor | Environmental stress & DNA damage | Prophage induction & replication strategy shift |

| Metabolic State Sensing | Nucleotide pools, ATP levels, translation machinery | Host metabolic activity & growth rate | Lysis timing & progeny yield |

Genomic Retention of Habitat Signals

Once acquired, environmental and host signals become embedded within phage genomes through multiple retention mechanisms that create durable, detectable signatures for microbial source tracking.

Auxiliary Metabolic Genes (AMGs) and Habitat Adaptation

Phages frequently encode auxiliary metabolic genes that redirect host metabolism toward phage replication, creating habitat-specific genomic signatures. These AMGs represent direct acquisitions from previous hosts that provide selective advantages in specific environments. The functional profiles of AMG content strongly correlates with habitat type and can serve as diagnostic markers [13] [8].

Environmental Specialization Examples:

- Freshwater Lakes: Limnohabitans phages from eutrophic Dianchi Lake carried AMGs for nucleotide metabolism, while those from oligotrophic Fuxian Lake encoded antibiotic resistance genes, reflecting adaptation to distinct trophic conditions [8].

- Wastewater Treatment: Phages in biological wastewater systems contain AMGs involved in carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur cycling, with gene complements specifically adapted to the high-nutrient, high-stress environment [13].

- Human Gut: Temperate phages from the human gut microbiome carry specialized AMGs for digesting host-derived polysaccharides and resisting bile salts, reflecting adaptation to the gastrointestinal environment [12].

CRISPR Spacer Acquisition and Host History

Phages themselves can harbor CRISPR-Cas systems that acquire spacers from competing genetic elements, creating a genomic record of previous encounters. Analysis of 741,692 phage genomes revealed that 3.7% contain CRISPR arrays with spacers targeting other phages or mobile genetic elements [9]. These spacer acquisitions provide:

- Historical Infection Records: Spacer sequences match regions of other phage genomes, documenting previous competitive interactions.

- Host Range Determination: Self-targeting spacers can limit host range and create niche specialization.

- Temporal Tracking: Spacer acquisition patterns reflect the evolutionary history of phage-phage interactions in specific environments.

Genomic Signature Retention Through Mutation Patterns

Phage genomes accumulate habitat-specific mutational patterns through selective pressures that create durable signatures:

- Host-Restricted Adaptation: Phages co-evolving with specific hosts accumulate mutations in tail fiber proteins that optimize receptor binding, creating host-specific phylogenetic clusters.

- Codon Usage Bias: Phages exhibit codon usage patterns that match their preferred hosts, reflecting long-term adaptation to specific bacterial taxa.

- GC Content Variation: Phage genomes often display GC content similar to their primary hosts, resulting from mutational biases and selection for efficient gene expression.

Table 2: Genomic Retention Mechanisms for Habitat Signals

| Retention Mechanism | Genomic Manifestation | Diagnostic Application | Persistence |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMG Content & Organization | Acquisition of host-derived metabolic genes | Habitat metabolic profiling & nutrient status | Stable, vertically inherited |

| CRISPR Spacer Acquisition | Spacer sequences from competing genetic elements | History of phage-phage interactions & host adaptation | Durable record of past encounters |

| Prophage Integration Sites | Specific bacterial attachment (att) sites | Host identification & strain tracking | Stable through bacterial generations |

| Mutation Spectrum & Rate | Host-specific codon usage & GC content | Long-term habitat adaptation & host range | Slowly accumulating but durable |

| Mobile Genetic Element Capture | Transposases, antibiotic resistance genes | Exposure to anthropogenic pollutants | Horizontally transferable |

Experimental Methodologies for Signal Detection

Deciphering phage ecogenomic signatures requires specialized experimental approaches that capture both genomic and phenotypic information.

Phage Isolation and Host Range Profiling

Protocol: Phage Isolation from Environmental Samples [8]:

- Sample Collection: Collect environmental samples (water, soil, biological specimens) in sterile containers.

- Host Preparation: Grow target bacterial strains to logarithmic phase in appropriate media (e.g., R2A for freshwater isolates).

- Enrichment Culture: Mix 10mL logarithmic-phase host culture with 30mL environmental sample, incubate overnight with aeration.

- Clarification: Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 20 minutes, filter supernatant through 0.22μm membrane.

- Plaque Assay: Combine filtered supernatant with fresh host culture, adsorb 20 minutes, add soft agar overlay, and incubate.

- Plaque Purification: Pick individual plaques, resuspend in sterile water, and repeat plaque assay through 3-5 serial dilutions.

- Phage Propagation: Prepare high-titer stocks from purified plaques for downstream analysis.

Host Range Determination: Test phage lysates against a panel of bacterial isolates using spot tests or efficiency of plating assays. Document lysis efficiency across multiple host species and strains to establish host range specificity [11].

Genomic Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

Protocol: Phage Genome Sequencing and Assembly [8] [9]:

- DNA Extraction: Concentrate phage particles by polyethylene glycol precipitation, treat with DNase I and RNase A to remove external nucleic acids, inactivate nucleases, then extract DNA using phenol-chloroform method or commercial kits.

- Library Preparation: Use Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore technologies appropriate for genome size and required resolution.

- Genome Assembly: Employ hybrid assembly approaches (Unicycler, SPAdes) for complete genome reconstruction.

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate genome completeness with CheckV, identify potential contaminants.

- Annotation: Predict open reading frames (Prokka, Pharokka), identify functional domains (HMMER, InterProScan), and classify taxonomically (geNomad, VICTOR).

AMG Identification Pipeline [9]:

- Gene Calling: Annotate protein-coding genes from phage genomes.

- Metabolic Annotation: Search against KEGG, COG, and Pfam databases.

- Cellular Function Filtering: Identify genes with predicted metabolic functions typically found in cellular organisms.

- Host Homology Assessment: Compare with host genomes to identify recently acquired genes.

- Functional Verification: Express genes in heterologous systems or analyze mutant phenotypes.

Prophage Induction and Integration Site Mapping

Protocol: Prophage Induction Profiling [12]:

- Induction Conditions: Apply diverse inducing agents including mitomycin C (0.3-3μg/mL), hydrogen peroxide (0.5mM), Stevia (3.7-37mg/mL), nutrient depletion, and host-derived signals.

- Community Co-culture: Construct synthetic microbial communities to simulate natural interactions.

- Host Factor Testing: Apply eukaryotic cell lysates (e.g., Caco-2 intestinal cells) to identify host-derived induction triggers.

- Induction Quantification: Monitor phage release through plaque assays or qPCR of structural genes.

- Integration Site Mapping: Use PCR walking or next-generation sequencing approaches to identify bacterial attachment sites.

Phage Signal Acquisition and Retention Pathway

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

The following toolkit summarizes critical reagents and methodologies for investigating phage ecogenomic signatures.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Phage Ecogenomic Studies

| Research Tool | Function & Application | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Induction Agents | Trigger prophage excision and lytic cycle | Mitomycin C (0.3-3μg/mL), hydrogen peroxide (0.5mM), Stevia (3.7-37mg/mL) [12] |

| Host Panel Arrays | Determine phage host range and specificity | Culture collections representing target bacterial taxa and related species [11] [8] |

| CRISPR Spacer Analysis Tools | Identify phage-host interaction history | CRISPRCasFinder, MiniCED, custom spacer databases [9] |

| AMG Annotation Pipeline | Identify metabolic genes in phage genomes | HMMER searches against KEGG, COG, TIGRFAM databases [13] [9] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Platforms | Resolve phenotypic heterogeneity in infected populations | NanoSIMS-SIP, BONCAT-FISH, microfluidic cultivation [14] |

| Phage Genome Databases | Reference data for comparative genomics | PGD50, IMG/VR, GenBank, GVD [9] |

| Genetic Engineering Systems | Modify phages for mechanistic studies | CRISPR-based phage engineering, rebooting systems, synthetic biology toolkits [10] |

Bacteriophages represent sophisticated natural biosensors that continuously acquire, retain, and update information about their hosts and habitats through defined molecular mechanisms. The core principles outlined in this technical guide provide a framework for exploiting these ecogenomic signatures in microbial source tracking research. As sequencing technologies advance and functional understanding of phage-host interactions deepens, phage-based tracking approaches will offer increasingly precise tools for mapping microbial contamination sources, reconstructing pathogen transmission pathways, and monitoring ecosystem health. The integration of phage ecogenomics with traditional microbiological approaches creates powerful synergies for addressing complex challenges in public health, environmental science, and biotechnology.

Bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant biological entities in the human body and across Earth's ecosystems. Their profound influence on microbial community structure, function, and evolution positions them as powerful tools for microbial source tracking (MST) research. This whitepaper synthesizes recent evidence from Nature family journals on the ecogenomic signatures of phages across three critical environments: the human gut, global oceans, and oral cavity. By examining phage diversity, host interaction dynamics, and environmental responses, we establish a foundation for leveraging phage genetic signatures as precise tracers of microbial origins and activities. These case studies demonstrate how phage ecogenomics can illuminate complex ecosystem dynamics and provide novel methodologies for tracking microbial contributions to human health and environmental processes.

Gut-Associated Phages: Induction Dynamics and Therapeutic Editing

Temperate Phage Induction in the Human Gut

The human gut microbiota contains a complex consortium of temperate phages existing as prophages integrated into bacterial genomes. A 2025 study provided unprecedented insights into the induction dynamics of these temperate phages from human gut bacterial isolates [12]. Through systematic analysis of 252 human gut bacterial isolates exposed to 10 different induction conditions, researchers characterized 134 inducible prophages, expanding experimentally validated temperate phage-host pairs from the human gut [12].

Table 1: Prophage Induction Across Bacterial Phyla in the Human Gut

| Bacterial Phylum | Isolates with Predicted Prophages | Isolates with Induced Prophages | Induced Prophage Predictions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidota | 44% (41/93) | 44% (41/93) | 27% (80/297) |

| Pseudomonadota | 94% (53/57) | 30% (17/57) | 12% (29/254) |

| Bacillota | 78% (40/51) | 20% (10/51) | 15% (16/109) |

| Actinomycetota | 86% (43/50) | 10% (5/50) | 8% (6/76) |

| Overall | 94% (237/252) | 32% (80/252) | 18% (134/736) |

Notably, only 18% of computationally predicted prophages could be experimentally induced in pure cultures, highlighting the limitation of prediction-only approaches [12]. Induction efficiency varied significantly across bacterial phyla, with Bacteroidota isolates showing the highest concordance between prediction and induction (27%), while Pseudomonadota, despite having the highest number of predicted prophages per isolate (4.5), showed only 12% induction rate [12].

A key finding was that human host-associated factors significantly influence prophage induction. When bacterial communities were co-cultured with human colonic epithelial cells (Caco2), induction rates increased to 35% of phage species, compared to 17% in community co-culture alone [12]. Furthermore, experiments with Caco2 cellular lysates induced 25 prophages, with nine previously undetected by standard induction agents, suggesting that human gastrointestinal cell lysis products may serve as natural induction triggers in vivo [12].

Longitudinal Phage-Bacteria Dynamics in Early Life

The development of phage communities in early life reveals fundamental patterns of microbial succession. A 2025 reanalysis of 12,262 longitudinal samples from 887 children in the TEDDY study provided unprecedented insight into phage-bacteria dynamics during the first four years of life [15]. Researchers developed the Marker-MAGu pipeline, creating a trans-kingdom profiling tool that simultaneously assesses phage and bacterial dynamics using a database of 49,111 phage taxa [15].

The study revealed that viral communities exhibit higher turnover rates than bacterial communities, with individuals harboring hundreds of distinct phages that accumulate into more diverse communities over time [15]. While bacterial species-level genome bins (SGBs) reached saturation in detection curves, viral SGBs did not, indicating substantially higher phage diversity [15]. Phage populations were highly individual-specific but showed clear ecological succession patterns that correlated with putative host bacteria abundance [16].

Notably, the addition of phage data improved machine learning models' ability to discriminate samples by geographic origin compared to bacterial data alone, highlighting the potential of phage signatures for tracking microbial origins [15]. In the context of type 1 diabetes, decreased rates of change in both bacterial and viral communities were observed in children aged one and two years who developed the condition, suggesting that phage dynamics could serve as ecosystem indicators for disease states [15].

Therapeutic Microbiota Editing with Phage Delivery Systems

Advanced phage delivery platforms represent a promising approach for precise gut microbiota editing. A 2025 study developed double-responsive hydrogel microspheres (HMs) for targeted oral phage delivery to treat bacterial colitis [17]. The HMs composed of sodium alginate, hyaluronic acid, and Eudragit S100 achieved 90% encapsulation efficiency for Salmonella-targeting phage cocktails and protected acid-sensitive phages from gastric conditions [17].

Table 2: Hydrogel Microsphere Sizes Based on Precursor Solution Concentration

| Precursor Solution Concentration | Microsphere Size (μm) | Application Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 133 ± 19 | Optimal for precision delivery in preclinical models |

| 3% | 347 ± 22 | Balanced protection and delivery |

| 6% | 890 ± 25 | Maximum protection, longer retention |

In a murine model of Salmonella Typhimurium-induced colitis, HMs-encapsulated phages reduced intestinal pathogen burden by nearly 2000-fold and lowered proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) to 60% of infected group levels [17]. The targeted phage approach achieved antibacterial efficacy comparable to ciprofloxacin while avoiding antibiotic-associated microbiota dysbiosis and diarrhea, effectively restoring gut homeostasis [17].

The electrohydrodynamic spraying method enabled precise control over microsphere size (100-900μm), with higher polymer concentrations producing denser surfaces that provided better protection against harsh gastrointestinal environments [17]. This platform demonstrates the potential for precise in situ microbiota editing by integrating targeted pathogen eradication with commensal microbiota conservation.

Marine Phages: Diversity and Biogeographic Patterns

Autographiviridae: A Dominant and Diverse Marine Phage Family

Marine viral communities harbor astounding diversity, with the double-stranded DNA phage family Autographiviridae among the most abundant in oceanic environments. A 2025 metagenomic study recovered 1,253 complete marine Autographiviridae uncultivated viral genomes (UViGs) from global datasets, revealing extensive previously uncharacterized diversity [18].

Phylogenomic analysis based on seven conserved core genes classified these marine Autographiviridae into 14 distinct groups, six of which were previously undescribed [18]. These groups varied significantly in genomic features including G+C content, genome size, and specific gene content, suggesting adaptation to different ecological niches and host ranges [18].

Metagenomic recruitment analysis demonstrated that Autographiviridae phages are globally distributed but enriched in upper ocean layers of tropical and temperate zones, with differential distribution patterns among groups mirroring the ecological niches of their potential hosts [18]. This phylogeographic patterning underscores the top-down control these phages exert on host populations and their potential as indicators of specific microbial processes in marine environments.

The core genome of marine Autographiviridae consisted of seven conserved genes, while accessory genes contributed to functional diversity and niche adaptation [18]. Host prediction efforts identified diverse bacterial taxa, including Cyanobacteria (Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus), SAR11 (Pelagibacterales order), and Roseobacter, highlighting the broad host range and ecological significance of this phage family in marine ecosystems [18].

Microviridae: Widespread ssDNA Phages Across Global Oceans

Small single-stranded DNA phages of the Microviridae family represent a prevalent yet understudied component of marine viral communities. A 2024 study isolated six novel Microviridae roseophages infecting Roseobacter RCA strains and identified 232 marine uncultivated virus genomes affiliated with the Occultatumvirinae subfamily from environmental datasets [19].

Genomic analysis revealed that the six roseophages had small circular genomes (5,409-5,978 nt) encoding 6-8 open reading frames, with conserved synteny of major capsid protein (VP1), DNA pilot protein (VP2), and replication initiator protein (VP4) genes [19]. Phylogenetic analysis based on concatenated VP1 and VP4 sequences placed these phages within the Occultatumvirinae/Family 7 cluster, representing the first isolation of marine Occultatumvirinae phages infecting Roseobacter [19].

Phylogenomic analysis of 433 Occultatumvirinae genomes (including the new isolates and UViGs) revealed 11 distinct subgroups with differential distribution patterns [19]. Metagenomic read-mapping showed global distribution of these microviruses, with two low G+C subgroups exhibiting particularly widespread prevalence across ocean basins. One phage in subgroup 2 was described as "extremely ubiquitous," suggesting successful adaptation to diverse marine conditions [19].

The study expanded the known diversity of ssDNA phages infecting ecologically important marine bacteria and provided insights into their distribution, highlighting the need to include these often-overlooked phages in marine microbial source tracking efforts.

Oral Phages: Database Development and Diversity

The Oral Phage Database: Expanding Oral Virome Knowledge

The oral cavity represents the second most diverse microbial habitat in the human body, yet its phage component remained largely unexplored until recent efforts. A 2025 study established the Oral Phage Database (OPD) through comprehensive analysis of 5,427 metagenomic samples and 2,178 cultivated bacterial genomes from diverse geographical populations [20].

The OPD comprises 189,859 representative phage genome sequences, including 3,416 huge phages with genomes exceeding 200 kbp, dramatically expanding the known diversity of oral viruses [20]. CheckV evaluation assigned 4,709 sequences (2.5%) as complete and high quality (>90% completeness) and 53,432 sequences (28.1%) as medium quality (50-90% completeness) [20]. The viral draft genomes (completeness >50%) had a median length of 48,519 bp and median completeness of 65.1%, providing substantial material for functional annotation and analysis [20].

Protein clustering analysis using vConTACT2 generated 9,983 sub viral clusters (subVCs), with 64.8% comprising only one member, indicating tremendous novel diversity distant from previously known phages [20]. Notably, oral phages exhibited little overlap with gut phage catalogs, revealing distinct phage compositions in these two body sites [20]. A total of 20,136 phage genomes did not cluster with genomes from other catalogs, highlighting the unique viral community of the oral cavity [20].

Geographic distribution analysis identified 33 subVCs present across all sampled countries, representing globally distributed phage strains that may infect globally distributed bacteria [20]. Additionally, 7,620 subVCs (79.65% of China-associated subVCs) were not detected in other countries, indicating substantial geographic patterning in oral phage communities [20].

Functional Capacity and Host Interactions of Oral Phages

Functional analysis of oral phages revealed several features with potential implications for bacterial ecology and human health. Numerous oral phages carry anti-defense genes, auxiliary metabolic genes, and virulence factors that may affect bacterial metabolism and influence human health [20]. The composition of oral phages varies among different populations, and several phages show potential as biomarkers for disease states [20].

The OPD enables systematic exploration of phage-bacteria interaction networks within the oral cavity, providing a resource for identifying specific phages that could serve as indicators of particular bacterial populations or physiological states. This has significant implications for oral health monitoring and understanding the role of phages in maintaining oral ecosystem balance or contributing to dysbiosis.

Experimental Methodologies for Phage Research

Key Experimental Protocols from Featured Studies

Prophage Induction Protocol (from Section 2.1): The induction of temperate phages from human gut bacterial isolates followed a standardized protocol [12]. Bacterial isolates were exposed to eight different induction conditions: standard medium control, mitomycin C (0.3 and 3 μg/ml), hydrogen peroxide (0.5 mM), Stevia sugar substitute (3.7 and 37 mg/ml), and two starvation conditions (50% carbon depletion and 100% short-chain fatty acid depletion) [12]. After induction, samples were processed for DNA extraction, and viral induction was confirmed through sequencing of 433 samples that passed inclusion criteria. Induced prophages were identified by comparing sequencing reads to computationally predicted prophage regions in bacterial genomes.

UViG Retrieval Protocol (from Section 3.1): The retrieval of uncultivated viral genomes from metagenomic data involved a multi-step bioinformatic pipeline [18]. Approximately 7 million UViGs were downloaded from multiple databases including IMG/VR, Global Ocean Viromes, and various regional virome studies [18]. Open reading frames were predicted using Prodigal, and three Autographiviridae core genes (RNA polymerase, phage capsid, and terminase large subunit) were used as baits to identify Autographiviridae UViGs through HMMER searches with strict cutoff values (e-value ≤10⁻³ and score ≥50) [18]. Genome completeness was assessed using CheckV, and only genomes with 100% completeness were used for subsequent phylogenomic and comparative analyses.

Oral Phage Database Construction (from Section 4.1): The OPD was constructed through comprehensive processing of 5427 oral metagenomes and 2178 cultivated bacterial genomes [20]. Over 670 million raw contigs were scanned by VirFinder and VirSorter2 to identify viral-like sequences [20]. A quality control pipeline filtered out contaminating mobile genetic elements, human sequences, and sequences shorter than 10 kbp (for metagenomes) or 1 kbp (for bacterial isolate genomes). Viral-like contigs with >95% nucleotide similarity were dereplicated, resulting in 189,859 non-redundant sequences that constituted the final database [20]. Taxonomic classification was performed using geNomad with the ICTV MSL39 database, and protein clustering was conducted with vConTACT2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Phage Ecogenomics

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mitomycin C | Chemical inducing agent for prophage induction | Triggering lytic cycle in temperate gut phages [12] |

| Sodium Alginate-Hyaluronic Acid-Eudragit S100 Hydrogel | pH-responsive phage delivery vehicle | Oral delivery of therapeutic phages to gut [17] |

| Electrohydrodynamic Spraying Platform | Fabrication of uniform hydrogel microspheres | Creating size-controlled phage encapsulation particles [17] |

| Prodigal Software | Protein-coding gene prediction in viral genomes | Identifying open reading frames in UViGs [18] |

| CheckV | Viral genome quality assessment | Estimating completeness and contamination of viral genomes [18] |

| VirSorter2 | Viral sequence identification from metagenomic data | Detecting viral sequences in oral metagenomes [20] |

| vConTACT2 | Viral taxonomy and clustering based on gene sharing | Classifying oral phages into viral clusters [20] |

| MetaPhlAn 4 + Marker-MAGu | Trans-kingdom microbiome profiling | Simultaneous detection of bacteria and phages in TEDDY study [15] |

Research Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Viral Ecogenomics Workflow: General pipeline for phage identification and analysis from environmental samples, with specific applications from marine and oral studies.

Diagram 2: Gut Prophage Induction Workflow: Experimental design for inducing and identifying temperate phages from human gut bacteria under different conditions.

The case studies presented herein demonstrate the power of phage ecogenomics for revealing ecosystem dynamics across diverse environments. Gut phages exhibit personalized temporal dynamics with potential for therapeutic manipulation; marine phages show distinct biogeographic patterns reflecting host ecology; and oral phages display unique compositional signatures with geographic variation. These ecogenomic signatures provide a foundation for advanced microbial source tracking methodologies that leverage phage communities as precise indicators of microbial origins and activities.

Future research directions should focus on integrating multi-environment phage databases, developing standardized protocols for phage source tracking, and establishing quantitative models linking phage signatures to specific microbial sources. The methodologies and findings summarized here provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with both the theoretical framework and practical tools needed to advance this emerging field, ultimately enabling more precise tracking of microbial contributions to human health and ecosystem functioning.

The detection of fecal contamination in water systems is a critical public health priority. Traditional methods, which rely on culturing fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) such as Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp., are hampered by significant limitations, including a lack of specificity to human feces, poor persistence in environmental waters, and long turnaround times [21]. Consequently, the development of advanced microbial source tracking (MST) tools is essential for safeguarding water quality.

The emerging field of phage ecogenomics offers a transformative approach. This whitepaper delineates the core advantages of using bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria—as indicators for microbial source tracking, focusing on their superior specificity, enhanced persistence, and exceptional abundance compared to traditional FIB. We will explore how the analysis of phage-encoded "ecogenomic signatures"—habitat-specific genetic patterns—provides a powerful, high-resolution framework for diagnosing the origin of fecal pollution [21].

The Case for Phages: Core Advantages in Microbial Source Tracking

The following table summarizes the principal advantages of bacteriophages over traditional fecal indicator bacteria.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Bacteriophages over Traditional Fecal Indicator Bacteria for Microbial Source Tracking

| Criterion | Traditional Fecal Indicator Bacteria (FIB) | Bacteriophages |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Low; lack of specificity to human faeces [21] | High; narrow host range and human gut-specific phage exist (e.g., ϕB124-14 infecting Bacteroides fragilis) [21] [22] |

| Persistence | Poor; susceptible to environmental decay and regrowth in certain environments, leading to false positives [21] | Enhanced; longer environmental persistence, providing a more reliable signal of past contamination [21] [22] |

| Abundance | Outnumbered by phage in most environments [22] | Exceptional; most abundant biological entities, often 10x more abundant than host bacteria [21] [22] |

| Utility for Culture-Independent Methods | Limited for direct, rapid detection | High; amenable to metagenomic analysis and PCR-based assays due to discernible habitat-associated ecogenomic signatures [21] [23] |

Specificity: Host Range and Ecogenomic Signatures

The specificity of bacteriophages operates on two levels: the molecular host-phage interaction and the ecological habitat association.

- Narrow Host Range: The high host-specificity of lytic bacteriophages is attributed to tail fiber proteins that selectively bind to receptors on a specific bacterial host's surface [22]. This enables the targeted detection of bacterial hosts indicative of a particular fecal source. For instance, phage ϕB124-14 infects a restricted set of human-associated Bacteroides fragilis strains, making it a highly specific marker for human fecal pollution [21].

- Ecogenomic Signatures: Beyond host range, phage genomes themselves encode habitat-associated signals. Research has demonstrated that individual phage genomes, such as ϕB124-14, carry a discernible "ecogenomic signature" based on the relative representation of their gene homologues in metagenomic datasets [21]. This signature can be used to segregate metagenomes according to their environmental origin (e.g., human gut vs. marine water) and can distinguish contaminated from uncontaminated samples with high discriminatory power [21].

Persistence and Abundance: Enhancing Detection Sensitivity

The utility of an indicator organism is contingent upon its ability to survive in the environment and be present in sufficient numbers for reliable detection.

- Enhanced Persistence: Bacteriophages generally exhibit a longer environmental persistence compared to their bacterial hosts [21] [22]. This characteristic makes them a more robust indicator of fecal pollution, especially where contamination occurred some time prior to sampling. Their durability reduces the likelihood of false negatives and provides a more accurate historical record of contamination events.

- Exceptional Abundance: With an estimated global population of approximately 10^31, bacteriophages are the most abundant biological entities on Earth [22]. They are found in great abundance in the human gut and are often more numerous than their bacterial hosts in environmental waters [21]. This high abundance increases the statistical probability of detection, thereby improving the sensitivity of MST assays.

Experimental Workflow for Ecogenomic Signature Analysis

The investigation of phage ecogenomic signatures for MST involves a multi-step process, from sample preparation to computational analysis. The workflow below outlines the key experimental and bioinformatic stages.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Techniques

Viral Metagenome Preparation from Water Samples

This protocol is adapted from procedures used in foundational ecogenomic studies [21] [24].

- Sample Collection: Collect a large volume of water (e.g., 1-10 liters) from the monitoring site.

- Differential Filtration: Process the sample through a series of filters (e.g., 0.45 μm and 0.2 μm Sterivex filters) to remove bacteria and larger particulates, allowing viruses to pass through into the filtrate.

- Virus Concentration:

- Precipitate viral particles from the filtrate using polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 and sodium chloride (overnight incubation at 4°C).

- Pellet the precipitate via centrifugation and resuspend in a small volume of SM buffer.

- Purification: Further purify the viral concentrate using density gradient centrifugation (e.g., CsCl gradient) to separate viruses from dissolved organic matter.

- DNA Extraction: Extract viral DNA using a commercial kit designed for viral nucleic acids (e.g., Qiagen MinElute Virus Spin Kit). The resulting DNA is suitable for downstream molecular analysis, including PCR and metagenomic sequencing.

Identification of Signature Genes Using PhiSiGns

PhiSiGns is a specialized bioinformatics tool designed to identify signature genes from phage genomes and design PCR primers for environmental surveys [25] [24].

- Input Genomes: Select completely sequenced phage genomes of interest (e.g., a group of T7-like podophages or Bacteroides phages) from a database like PhAnToMe.

- Pairwise Comparison: The tool performs an all-against-all BLASTP comparison of all predicted open reading frames (ORFs) from the selected genomes.

- Signature Gene Identification: Genes that are conserved (homologous) across the user-defined group of phages are identified as potential signature genes.

- Primer Design:

- The tool generates a multiple sequence alignment of the signature gene.

- A consensus sequence is built, and conserved regions are identified.

- Degenerate PCR primers are designed from these regions, with user-controlled parameters for melting temperature, GC content, product size, and degeneracy.

Quantifying Ecogenomic Signatures in Metagenomes

This methodology tests the hypothesis that a phage encodes a habitat-specific signal [21].

- Reference Set Creation: Use the protein sequences of all ORFs from a candidate phage (e.g., ϕB124-14) as a reference set.

- Metagenomic Query: Search a collection of metagenomes from various habitats (e.g., human gut, bovine gut, marine water) against this reference set using BLAST or similar tools.

- Abundance Calculation: For each metagenome, calculate the cumulative relative abundance of sequences that generate significant hits to the reference ORFs. This metric represents the strength of the phage's ecogenomic signature in that environment.

- Statistical Discrimination: Apply statistical tests to determine if the signature is significantly enriched in target habitats (e.g., human gut) compared to non-target environments. This demonstrates the signature's discriminatory power for MST.

The following table catalogs key reagents, tools, and bioinformatics resources essential for research into phage ecogenomic signatures.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Phage Ecogenomics

| Item Name | Type/Category | Key Function in Research | Example(s) / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides Phage ϕB124-14 | Model Organism | A well-characterized phage infecting human-associated Bacteroides fragilis; model for studying human gut-specific ecogenomic signatures [21]. | Used to demonstrate that individual phage can encode clear habitat-related signals diagnostic of the underlying human gut microbiome [21]. |

| Signature Genes | Molecular Target | Conserved, homologous genes used as markers to study diversity and phylogeny of specific phage groups in environmental samples [23] [24]. | Examples include structural protein genes (g20, g23, mcp), auxiliary metabolic genes (psbA, phoH), and polymerase genes (g43, polA) [23]. |

| PhiSiGns | Bioinformatics Tool | Web-based application that identifies signature genes from user-selected phage genomes and designs PCR primers for amplifying them from environmental samples [25] [24]. | Facilitates the development of novel molecular markers for phage diversity studies; available at http://www.phantome.org/phisigns/. |

| Viral Metagenomes (Viromes) | Data Type | Sequence data derived from the viral fraction of an environment; used to profile the structure and genetic content of natural viral communities [21]. | Publicly available viromes from habitats like the human gut, porcine gut, and marine waters are used for ecological profiling and signature validation [21]. |

| CsCl Gradient Centrifugation | Laboratory Technique | A purification method used to isolate and concentrate viral particles from complex environmental samples based on their buoyant density [24]. | Critical for obtaining pure viral DNA for metagenomic sequencing, free from contaminating bacterial DNA. |

Bacteriophages present a paradigm shift in microbial source tracking, offering tangible and significant advantages over traditional indicator bacteria. Their high specificity, both in terms of host interaction and encoded ecogenomic signatures, allows for precise identification of pollution sources. Coupled with their enhanced environmental persistence and global abundance, phages provide a robust, sensitive, and reliable signal for water quality monitoring. The integration of modern molecular techniques, such as metagenomics and tailored bioinformatics tools like PhiSiGns, enables researchers to decode the complex ecological information carried by phage populations. As this field advances, the development of standardized, phage-based assays promises to greatly enhance our ability to protect public health by ensuring the safety of water resources.

From Sequence to Source: Methodologies for Signature Extraction and Application

The study of viral communities, particularly bacteriophages, is fundamental to understanding microbial ecosystems. Metagenomic sequencing has emerged as a powerful, culture-independent approach for characterizing these viral populations, leading to two predominant methodological strategies: virus-like particle (VLP) enrichment and whole-community (bulk) metagenomics. These approaches differ significantly in their implementation and outcomes, influencing the interpretation of viral community ecology [26]. Within this framework, the discovery of phage-encoded ecogenomic signatures—genetic patterns within bacteriophage genomes that are diagnostic of their habitat of origin—has created new opportunities for applied research. Specifically, these signatures enable Microbial Source Tracking (MST), a method to identify faecal contamination in water and determine its human or animal origin [21]. The choice between VLP and whole-community approaches directly impacts the detection and resolution of these critical ecological signals, making methodological understanding essential for researchers in environmental microbiology and public health.

Core Methodological Approaches: A Technical Comparison

The two primary metagenomic strategies capture different fractions of the viral community, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

VLP-Enrichment Strategies

VLP-based methods physically separate virus-like particles from cellular material prior to nucleic acid extraction. This typically involves a series of filtration and centrifugation steps designed to remove bacterial cells and debris, thereby enriching for free viral particles [26] [27]. Common protocols include modified versions of the Novel Enrichment Technique of Viromes (NetoVIR) [27]. A key feature of this approach is that it predominantly captures virion-derived DNA, representing viruses in the extracellular, lytic phase of their life cycle at the time of sampling [26].

Whole-Community (Bulk) Metagenomics

In contrast, the whole-community approach extracts total nucleic acids directly from a sample without prior separation of viral particles. This method simultaneously captures DNA from all domains of life—viruses, bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes—present in the sample [27]. Consequently, it detects viral sequences in both integrated (lysogenic) and intracellular states, providing context for virus-host relationships that VLP-based methods miss [26]. However, viral sequences can be dwarfed by the overwhelming amount of host and bacterial DNA, making their detection computationally challenging and potentially less sensitive for rare viruses [26] [27].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of VLP-Enrichment vs. Whole-Community Metagenomics

| Parameter | VLP-Enriched Metagenomes | Whole-Community Metagenomes |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Viral Sequence Yield | Higher proportion of viral sequences [26] | Lower proportion; dominated by bacterial/host DNA [26] [27] |

| Viral Richness (Species Diversity) | Generally higher species richness observed [26] | Lower apparent richness for viruses [26] |

| Detection of Integrated/Prophage Viruses | Limited | Comprehensive [26] |

| Required Sequencing Depth | Lower (due to enrichment) [27] | Higher (to sufficiently capture viral minority) [27] |

| Computational Demand for Viral Identification | Lower | Higher [27] |

| Representation of Active (Lytic) Community | Better reflects extracellular, lytic phase [26] | Better reflects intracellular and integrated states [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Viral Metagenomics

Detailed methodologies are critical for reproducibility. The following protocols, adapted from comparative studies, highlight the key differences in processing samples for viral metagenomics.

Protocol for Whole-Community (Bulk) Metagenomics

This protocol is designed to extract total DNA from a stool sample, capturing all genetic material present [27]:

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the stool solution at maximum speed (e.g., 20,000 × g). Discard the supernatant.

- Lysis and Inhibition Removal: Resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of InhibitEX Buffer (or similar) and add 20 μL of lysozyme. Incubate for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Mechanical Disruption: Add 200 μL of acid-washed glass beads and heat the sample for 5 minutes at 95°C.

- Clarification: Centrifuge at maximum speed for 1 minute. Transfer 600 μL of the supernatant to a new tube.

- Digestion and Binding: Add 20 μL of Proteinase K, followed by 600 μL of Buffer AL. Incubate at 70°C for 10 minutes.

- DNA Purification: Add 600 μL of absolute ethanol. Transfer the mixture to a spin column. Perform two wash steps using Buffer AW1 and AW2.

- Elution: Elute the DNA with 50 μL of elution buffer (ATE). Quantify the DNA yield using a fluorometric method like the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit.

Protocol for VLP-Enrichment (Modified NetoVIR)

This protocol enriches for viral particles before DNA extraction, reducing non-viral DNA [27]:

- Clarification and Filtration:

- Homogenize the fecal suspension and centrifuge at 17,000 × g for 3 minutes.

- Recover at least 200 μL of the supernatant and filter it through a 0.8 μm filter via centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 1 minute. This step removes most bacteria and debris.

- Nuclease Treatment: To the filtered supernatant, add a premade mix of resolving enzymes (e.g., DNase and RNase) to degrade free-floating nucleic acids not protected within a viral capsid.

- Viral Lysis and Nucleic Acid Extraction: Lyse the intact VLPs to release their protected nucleic acids. This is typically followed by a standard nucleic acid extraction and purification protocol, such as the QIAamp Mini kit, but optimized for the low yields expected from viral fractions.

- Whole-Transcriptome Amplification (Optional): Due to the low nucleic acid yield, an amplification step like WTA may be required to generate sufficient material for sequencing. It is crucial to include multiple negative controls (e.g., for the extraction and RT-PCR steps) to monitor for contamination introduced during amplification [27].

The following workflow diagram synthesizes these protocols into a single, comparable visual structure, highlighting the divergent paths taken by each method from a single sample.

Ecogenomic Signatures for Microbial Source Tracking

The methodological choice between VLP and whole-community approaches has a direct impact on the detection and application of phage ecogenomic signatures. Research has demonstrated that individual bacteriophages carry a discernible habitat-associated signal based on the relative abundance of their gene homologues in metagenomic datasets [21] [6].

A key example is the gut-associated bacteriophage φB124-14, which infects human-associated Bacteroides fragilis. Analysis of its open reading frames (ORFs) shows a significantly higher cumulative relative abundance in human gut viromes compared to environmental viromes, forming a distinct human gut ecogenomic signature [21]. This signature is powerful enough to segregate metagenomes by environmental origin and can distinguish environmental metagenomes subjected to simulated human faecal pollution from uncontaminated ones [21] [6].

The detection efficacy of this signature is method-dependent:

- In VLP-Enriched Viromes: The φB124-14 ecogenomic signature shows clear enrichment in human gut viromes compared to environmental or other gut viromes, providing high discriminatory power [21].

- In Whole-Community Metagenomes: The signature is less pronounced. While there is still a significant decrease in signature abundance at non-gut human body sites compared to the gut, the difference between human gut metagenomes and environmental datasets is not always significant [21]. This suggests that while whole-community metagenomes capture the integrated prophage community, the "signal-to-noise ratio" for this specific application can be lower.

This principle is illustrated in the following diagram, which traces the journey from sample collection to the final application in water quality monitoring.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of viral metagenomics requires specific laboratory reagents and computational tools. The following table catalogs key solutions used in the featured protocols and analyses.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Metagenomics

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Protocol / Context |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | DNA extraction from complex stool samples. | Whole-community metagenomics protocol [27]. |

| InhibitEX Buffer | Binds PCR inhibitors common in faecal and environmental samples. | Whole-community metagenomics protocol [27]. |

| RNAlater Solution | Preserves and stabilizes RNA integrity in samples during storage and transport. | Sample collection and preservation for RNA virome studies [27]. |

| DNase & RNase Enzymes | Degrades unprotected nucleic acids outside of viral capsids during VLP enrichment. | VLP-enrichment protocol (NetoVIR) [27]. |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Fluorometric quantification of low-yield double-stranded DNA; more accurate for dilute samples than spectrophotometry. | DNA quantification post-extraction [27]. |

| MetaSPAdes / MEGAHIT | De novo assemblers for metagenomic short reads into contigs. | Sequence assembly in bioinformatic workflow [26] [28]. |

| VIBRANT | Tool for identifying viral contigs from metagenomic assemblies and assessing their lytic/lysogenic potential. | Viral sequence identification and analysis [26]. |

| Kraken 2 / MetaPhlAn 4 | Tools for taxonomic profiling of sequencing reads or contigs. | Community composition analysis and classification [28]. |

The decision to employ VLP-enrichment or whole-community metagenomics is not a matter of selecting a universally superior method, but rather of aligning the methodology with the specific research question. For studies focused explicitly on the free viral particle community, such as tracking active lytic infections or developing sensitive MST tools based on virion-associated ecogenomic signatures, VLP-enrichment offers greater sensitivity and richness [26] [21]. Conversely, for investigations into virus-host interactions, lysogeny, and the broader ecological context of viruses within the entire microbial community, whole-community metagenomics is indispensable [26].

Future research will benefit from standardized protocols to improve cross-study comparisons. Furthermore, the emerging paradigm of methodological pairing—using both VLP and whole-community approaches on the same sample—is highly recommended to maximize coverage and obtain a more holistic understanding of viral community structure, function, and ecology [26]. As sequencing technologies and bioinformatic tools continue to advance, the integration of these complementary approaches will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of phage ecogenomic signatures in both fundamental research and applied public health.

Microbial Source Tracking (MST) is a critical discipline for safeguarding public health, aiming to identify the origin of fecal contamination in water bodies. Traditional methods rely on fecal indicator bacteria but fail to distinguish between human and animal sources. Bacteriophages (phages), viruses that infect bacteria, have emerged as powerful alternative indicators due to their high host specificity, environmental stability, and abundance in human and animal guts [29] [30]. The core premise of using phage ecogenomic signatures lies in the fact that different animal hosts harbor distinct bacterial communities, which in support unique phage populations. Therefore, analyzing phage genomic signatures in environmental samples can trace contamination back to its source.

This whitepaper details the core bioinformatic workflows for analyzing phage genomic data, focusing on tetranucleotide frequency analysis and machine learning tools. These methods enable the extraction of robust ecogenomic signatures from phage genomes and metagenomes, providing researchers with a powerful toolkit for high-resolution MST.

Tetranucleotide Frequency Analysis: Principles and Workflows

Theoretical Foundations

Tetranucleotide Frequency (TNF) refers to the normalized count of all possible 4-base sequences (256 possible combinations) in a genomic sequence. It serves as a powerful genomic signature because it is remarkably stable across entire genomes from the same organism but varies significantly between different organisms. This signature reflects a combination of species-specific factors, including codon usage bias, DNA structural preferences, and methylation patterns [31]. For phages, which often lack universal marker genes, TNF provides a alignment-free method for comparative genomics, allowing for taxonomic classification, host prediction, and the binning of metagenomic contigs into population-level units.

Computational Tools and Implementation

The calculation of TNF is integrated into many bioinformatics pipelines. The process typically involves: 1) Sequence Preprocessing (quality control, assembly), 2) k-mer Counting (e.g., using jellyfish), and 3) Normalization (e.g., Z-score normalization) to make frequencies comparable across sequences of different lengths. TNF is a key feature in tools like PhageScanner [32] and is fundamental to the analysis of Uncultivated Viral Genomes (UViGs) [33].

Table 1: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Phage Genome Analysis, Including TNF Applications

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Relevance to TNF & Machine Learning | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhageScanner | A reconfigurable ML framework for phage feature annotation. | Employs k-mer-based features (including tetranucleotides) for training models to predict Virion Proteins (PVPs) and toxins. [32] | Frontiers in Microbiology |

| PhANNs | Phage Artificial Neural Networks for protein classification. | Uses genomic features for multiclass classification of phage proteins; a precursor to PhageScanner. [32] | Cantu et al., 2020 |

| DeePVP | Deep learning for PVP prediction. | A convolutional neural network that uses protein sequences; demonstrates advanced ML application in phage genomics. [32] | Fang et al., 2022 |

| VirION2 | Pipeline for identifying viral sequences in metagenomes. | Relies on features like TNF for binning and classifying viral contigs from complex metagenomic data. [33] | PMC Article |

| MetaSPAdes/ViralAssembly | Metagenomic assemblers. | Critical first step for generating phage genomes from metagenomic reads, which can then be used for TNF analysis. [33] | Sutton et al. |

Figure 1: A standardized bioinformatic workflow for tetranucleotide frequency analysis, from raw sequencing data to application in microbial source tracking.

Experimental Protocol for TNF-Based Phage Analysis

Objective: To identify and bin phage contigs from a metagenomic sample (e.g., river water) based on their tetranucleotide signatures for source tracking.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection & DNA Sequencing: Collect water samples. Filter to enrich for viral particles. Extract DNA and prepare libraries for shotgun metagenomic sequencing on an Illumina platform [34].

- Quality Control & Assembly: Process raw reads with

Fastp(v0.23.2) to trim adapters and remove low-quality reads [35]. Perform de novo assembly usingMetaSPAdes(v3.15.0) orMEGAHIT(v1.2.9) to reconstruct longer contigs [33]. - Phage Contig Identification: Identify phage-derived contigs from the assembly using a tool like

VirION2[33] orCheckV(v1.0.1) [35], which assesses completeness and removes contamination. - Tetranucleotide Frequency Calculation: Use a custom Python script or a tool like