Decoding Bacterial Evolution: A Genomic Guide to Identifying Niche-Specific Adaptive Genes

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategies and tools for identifying niche-specific bacterial adaptive genes.

Decoding Bacterial Evolution: A Genomic Guide to Identifying Niche-Specific Adaptive Genes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategies and tools for identifying niche-specific bacterial adaptive genes. It explores the foundational principles of bacterial genome evolution, including horizontal gene transfer and gene loss. The content details state-of-the-art bioinformatics methodologies, from comparative genomics to machine learning workflows like bacLIFE. It further addresses common analytical challenges and optimization techniques, and concludes with frameworks for the experimental and computational validation of candidate genes. The synthesis of these areas aims to accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and inform strategies to combat antibiotic resistance.

The Genetic Playbook: Core Principles of Bacterial Niche Adaptation

Niche adaptation is the process by which organisms evolve genetic and functional characteristics that enable them to thrive in specific environmental contexts. For bacterial pathogens, understanding these adaptive mechanisms is crucial for elucidating host-pathogen interactions, tracking the emergence of infectious diseases, and developing targeted antimicrobial strategies [1]. This field has gained particular importance within the "One Health" framework, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health [1].

The genomic diversity of pathogens plays a crucial role in their adaptability across different niches. Bacteria employ two primary genetic mechanisms for adaptation: gene acquisition through horizontal gene transfer and gene loss through reductive evolution [1]. For instance, Staphylococcus aureus has acquired host-specific immune evasion factors, methicillin resistance determinants, and lactose metabolism genes through horizontal gene transfer, while Mycoplasma genitalium has undergone extensive genome reduction to maintain a mutualistic relationship with its host [1].

Quantitative Landscape of Bacterial Niche Adaptation

Comparative genomic analyses of 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes across different niches have revealed significant variability in bacterial adaptive strategies [1]. The table below summarizes key genomic differences identified across ecological niches.

Table 1: Niche-Specific Genomic Features in Bacterial Pathogens

| Ecological Niche | Enriched Functional Categories | Key Adaptive Genes/Pathways | Notable Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Host | Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), immune modulation factors, adhesion factors | hypB (metabolism/immune adaptation), higher virulence factor load | Pseudomonadota |

| Animal Host | Virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes (reservoirs) | Fluoroquinolone resistance genes | Staphylococcus aureus |

| Clinical Settings | Antibiotic resistance mechanisms | Fluoroquinolone resistance determinants | Multiple drug-resistant pathogens |

| Environmental Sources | Metabolic pathways, transcriptional regulation | Genes for environmental sensing and nutrient utilization | Bacillota, Actinomycetota |

Table 2: Adaptive Strategies Across Bacterial Phyla

| Bacterial Phylum | Primary Adaptive Strategy | Niche Preference | Genomic Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonadota | Gene acquisition | Human hosts | Higher virulence factors, carbohydrate-active enzymes |

| Actinomycetota | Genome reduction | Environmental sources | Metabolic versatility, transcriptional regulation |

| Bacillota | Genome reduction | Environmental sources | Environmental adaptability, metabolic diversity |

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Niche-Adaptive Genes

Genome Collection and Quality Control

Purpose: To construct a high-quality, non-redundant genome collection for robust comparative analysis [1].

Procedure:

- Source genomes from databases (e.g., gcPathogen)

- Apply stringent quality filters:

- Exclude sequences assembled only at contig level

- Retain genomes with N50 ≥50,000 bp

- Keep genomes with CheckM completeness ≥95% and contamination <5%

- Remove genomes with unclear source information

- Annotate ecological niches based on isolation source and host information (human, animal, environment)

- Reduce redundancy by calculating genomic distances using Mash and performing Markov clustering, removing genomes with distances ≤0.01

- Verify taxonomic information and exclude mismatched sequences

Expected Output: 4,366 high-quality, non-redundant pathogen genome sequences with verified ecological niche labels [1].

Phylogenetic Analysis and Population Structure

Purpose: To control for phylogenetic relationships when identifying niche-specific adaptations [1].

Procedure:

- Identify marker genes: Retrieve 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome using AMPHORA2

- Perform multiple sequence alignment for each marker gene using Muscle v5.1

- Concatenate alignments into a comprehensive multiple sequence alignment

- Construct maximum likelihood tree using FastTree v2.1.11

- Determine optimal clustering: Convert phylogenetic tree to evolutionary distance matrix using R package ape

- Perform k-medoids clustering using pam function from R cluster package

- Calculate average silhouette coefficient for k values 1-10 to determine optimal cluster number (k=8 based on maximum average silhouette coefficient of 0.63)

Functional Annotation and Enrichment Analysis

Purpose: To identify functional categories and virulence mechanisms associated with specific niches [1].

Procedure:

- Predict open reading frames (ORFs) using Prokka v1.14.6

- Functional categorization:

- Map ORFs to Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST (e-value threshold 0.01, minimum coverage 70%)

- Annotate carbohydrate-active enzymes:

- Use dbCAN2 to map ORFs to CAZy database

- Filter annotations using hmm_eval 1e-5, retaining only HMMER tool annotations

- Identify virulence factors:

- Map genomes to Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) using ABRicate v1.0.1 with default parameters

- Detect antibiotic resistance genes:

- Map genomes to Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) using ABRicate

Identification of Signature Adaptive Genes

Purpose: To statistically identify genes significantly associated with specific ecological niches [1].

Procedure:

- Apply genome-wide association approaches using Scoary to identify niche-associated genes

- Validate associations using machine learning algorithms to enhance predictive accuracy

- Perform functional validation of candidate genes (e.g., hypB for human adaptation) through experimental follow-up

Visualization of Niche Adaptation Pathways

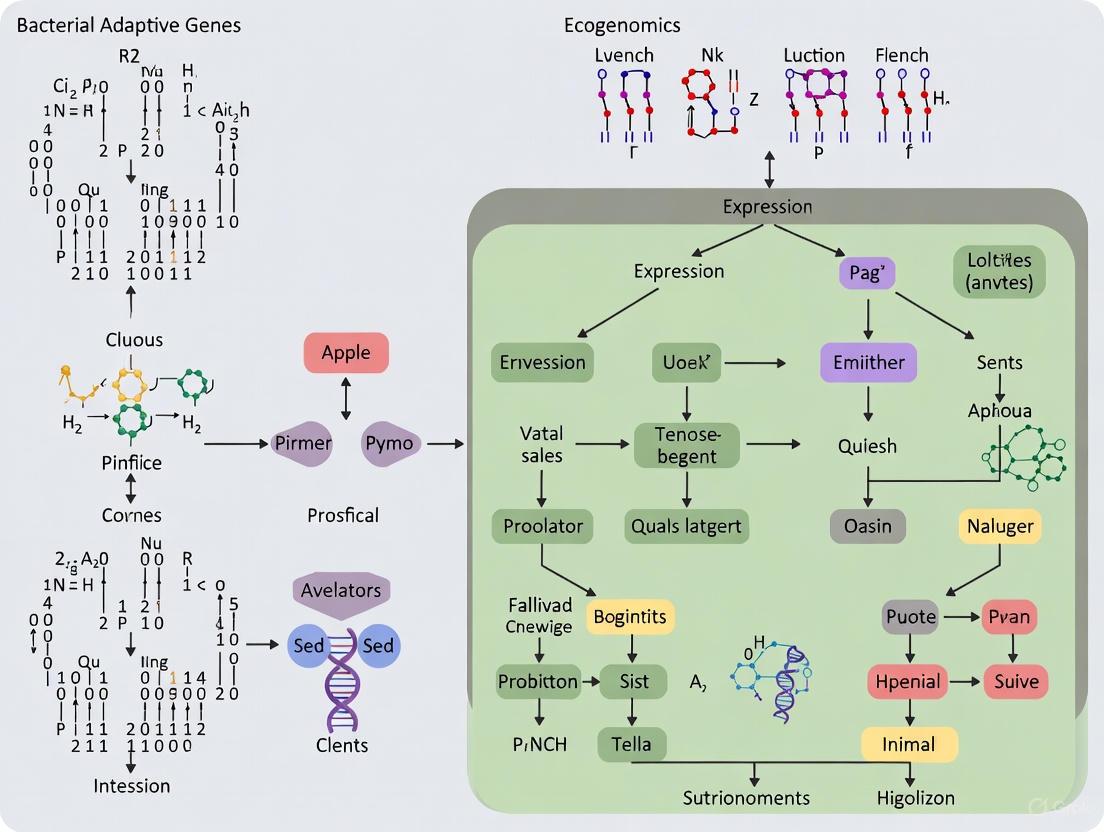

The following diagram illustrates the genomic adaptation pathways bacteria employ when transitioning between different ecological niches:

Genomic Adaptation Pathways in Bacterial Niches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Niche Adaptation Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| gcPathogen Database | Source of bacterial genome sequences and metadata | Genome collection and niche annotation [1] |

| CheckM | Assess genome quality and completeness | Quality control filtering [1] |

| Mash | Calculate genomic distances between sequences | Redundancy reduction [1] |

| AMPHORA2 | Identify universal single-copy marker genes | Phylogenetic tree construction [1] |

| Muscle v5.1 | Perform multiple sequence alignment | Phylogenetic analysis [1] |

| FastTree v2.1.11 | Construct maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees | Evolutionary relationship analysis [1] |

| Prokka v1.14.6 | Annotate bacterial genomes and predict ORFs | Functional annotation [1] |

| COG Database | Classify genes into functional categories | Functional categorization [1] |

| dbCAN2 & CAZy Database | Annotate carbohydrate-active enzymes | Metabolic adaptation analysis [1] |

| VFDB | Identify virulence factors | Pathogenic mechanism analysis [1] |

| CARD | Detect antibiotic resistance genes | Resistance profiling [1] |

| Scoary | Identify pan-genome associations with traits | Signature adaptive gene detection [1] |

In the relentless pursuit of survival, bacteria deploy distinct genomic strategies to adapt to new ecological niches. Two of the most significant are Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT), the acquisition of external genetic material, and Genome Reduction, the evolutionary loss of non-essential genes. HGT acts as a rapid gene acquisition system, allowing bacteria to gain novel traits from donors across the tree of life. In contrast, Genome Reduction streamlines the genome, purging superfluous DNA to optimize energy use in stable environments. For researchers focused on identifying niche-specific bacterial adaptive genes, understanding the contexts, mechanisms, and experimental approaches for studying these two strategies is paramount. This Application Note provides a structured comparison of these strategies and details protocols for their investigation, framed within the scope of microbial adaptation research.

Strategic Comparison and Applications

The choice between HGT and Genome Reduction as a primary adaptive strategy is heavily influenced by environmental pressure and niche characteristics. The following table summarizes their core attributes and ecological contexts.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Horizontal Gene Transfer and Genome Reduction

| Feature | Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) | Genome Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Acquisition of foreign genetic material from donors | Loss of genomic DNA and non-essential genes |

| Primary Evolutionary Effect | Genome expansion and innovation; increased functional diversity | Genome streamlining; optimization of resources |

| Typical Niches | Dynamic, stressful, or novel environments [2] [3] | Stable, nutrient-poor, or host-restricted environments |

| Pace of Adaptation | Rapid; single-event acquisition of complex traits [2] [4] | Gradual; occurs over many generations |

| Key Functional Impacts | Spread of antibiotic resistance, virulence factors, and catabolic pathways [3] | Loss of regulatory functions, redundancy, and biosynthetic pathways; increased auxotrophy |

| Representative Organisms | E. coli (industrialized gut microbiome), Psychrophiles, Halophiles [2] [3] | Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Obligate intracellular symbionts |

HGT is a dominant force in rapidly changing environments. Evidence shows that industrialized human gut microbiomes exhibit elevated HGT rates, with transferred gene functions reflecting host lifestyle, such as adaptations to dietary shifts or xenobiotics [3]. Similarly, HGT is a key mechanism for adapting to extreme environments like high salinity, temperature, or acidity, allowing organisms to acquire pre-evolved, beneficial genes from other extremophiles [2].

Genome Reduction, while less flashy, is a powerful adaptation to constant, resource-limited conditions. The genome-reduced bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae serves as an excellent model for studying this phenomenon. Its small genome (816 kb) has been shaped by reductive evolution, making it ideal for high-resolution essentiality studies [5].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting Horizontal Gene Transfer

Detecting HGT relies on phylogenetic incongruence and genomic signature analyses.

Methodology:

- Genome Assembly & Annotation: Sequence and assemble the genome of the target bacterium. Annotate genes using standard tools (e.g., Prokka, RAST).

- Dataset Construction: For a gene of interest, compile a comprehensive set of homologues from diverse taxonomic groups, including potential donors and recipients.

- Species Tree Reconstruction: Construct a robust species tree using concatenated, rarely transferred informational genes (e.g., ribosomal proteins). This tree serves as a reference [6].

- Gene Tree Reconstruction: Build a phylogenetic tree for the gene of interest using the same set of species.

- Incongruence Detection: Compare the gene tree to the species tree. Significant topological conflicts, especially those that group distantly related species to the exclusion of close relatives, indicate potential HGT [6].

- Validation with Similarity/Distance Plots (SimPlot/DistPlot): Use a sliding window approach across the aligned gene sequence. A region that shows significantly higher similarity (or lower distance) to a distant donor species than to its own species clade provides strong evidence for recombination and HGT [6].

- Functional Impact Assessment: Experimentally validate the function of the horizontally acquired gene through gene knockout/complementation and phenotype assays (e.g., growth under specific stress conditions).

Protocol 2: Mapping Gene Essentiality in Genome-Reduced Bacteria

High-resolution transposon mutagenesis can define the core essential genome and identify non-essential regions within essential genes.

Methodology (Adapted from [5]):

- Transposon Library Design:

- Engineer two Tn4001-based transposon vectors.

- Promoter Library (pMTnCatBDPr): Contains outward-facing promoters to minimize polar effects on downstream genes.

- Terminator Library (pMTnCatBDter): Contains outward-facing terminators to disrupt transcription.

- Library Generation and Selection:

- Transform the genome-reduced bacterium (e.g., Mycoplasma pneumoniae) with the transposon libraries.

- Grow the pooled mutant libraries over multiple serial passages (e.g., 10 passages) to select against mutants with fitness defects.

- Tn-Seq and Data Analysis:

- Harvest cells at multiple time points. Extract genomic DNA and perform next-generation sequencing of transposon insertion sites using a tool like FASTQINS [5].

- Essentiality Mapping: Genomic regions with no or very few transposon insertions after selection are classified as essential. Regions tolerant to insertions are non-essential.

- High-Resolution Analysis:

- Combine data from both libraries to achieve near-single-nucleotide resolution.

- Identify essential protein domains and structural regions within essential genes that tolerate disruptions, leading to functionally split proteins [5].

Visualization of Workflows

HGT Detection via Phylogenetic Incongruence

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for detecting Horizontal Gene Transfer through phylogenetic analysis.

High-Resolution Essentiality Mapping

The diagram below outlines the experimental workflow for mapping gene essentiality at high resolution in genome-reduced bacteria.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential materials and reagents for conducting the experiments described in this note.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Strategy Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| pMTnCat_BDPr Vector | Engineered transposon with outward-facing promoters; minimizes polar effects in Tn-Seq. | Used for high-resolution essentiality mapping in M. pneumoniae [5]. |

| pMTnCat_BDter Vector | Engineered transposon with outward-facing terminators; disrupts transcriptional readthrough. | Complementary library to assess impact of reduced transcription [5]. |

| FASTQINS | Bioinformatics software for precise identification of transposon insertion sites from NGS data. | Critical for processing Tn-Seq data and generating insertion maps [5]. |

| Ribosomal Protein Genes | Concatenated sequences used to reconstruct a robust species tree for HGT detection. | Informational genes that are rarely transferred, providing a reliable phylogenetic reference [6]. |

| SimPlot/DistPlot Software | Sliding window analysis to detect regions of similarity/distance between sequences. | Validates HGT events and identifies recombination breakpoints [6]. |

Understanding the genetic mechanisms that enable bacterial pathogens to adapt to specific ecological niches is a cornerstone of modern microbial genomics and a critical focus for therapeutic development. Genomic diversification, driven by host-microbe interactions, allows pathogens to survive across diverse environments, from human hosts to animals and external reservoirs [7]. This application note delineates a detailed protocol for identifying these niche-specific "signature adaptations," focusing on three key genomic elements: Virulence Factors (VFs), Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes), and Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs). The content is framed within a broader thesis on identifying bacterial adaptive genes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a robust framework for comparative genomic analysis. We summarize key quantitative findings from a large-scale study of 4,366 bacterial genomes and provide step-by-step methodologies for replicating and extending this research [7] [1].

A large-scale comparative genomic analysis reveals distinct enrichment patterns of key adaptive genes across different bacterial niches. The tables below summarize these core findings for easy comparison.

Table 1: Niche-Specific Enrichment of Key Genomic Elements in Bacterial Pathogens

| Ecological Niche | Enriched Genomic Elements | Associated Bacterial Phyla | Proposed Adaptive Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-Associated | CAZymes; VFs for immune modulation and adhesion [7] | Pseudomonadota [7] | Gene acquisition [7] |

| Clinical Settings | Antibiotic Resistance Genes (e.g., fluoroquinolone resistance) [7] | - | Survival under therapeutic pressure |

| Animal-Associated | Reservoirs of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes [7] | - | - |

| Environmental | Genes for metabolism and transcriptional regulation [7] | Bacillota, Actinomycetota [7] | Genome reduction [7] |

Table 2: Key Databases for Annotating Bacterial Adaptive Genes

| Database Name | Primary Function | Key Annotated Elements | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VFDB | Identification of Virulence Factors | VFs for adhesion, toxin production, immune evasion, etc. [8] [9] | http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/ [8] |

| CAZy | Identification of Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes | Glycoside Hydrolases (GHs), GlycosylTransferases (GTs), etc. [10] [11] | http://www.cazy.org/ [10] |

| CARD | Identification of Antibiotic Resistance Genes | ARGs for drug inactivation, efflux pumps, target protection [7] | - |

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Signature Adaptations

Protocol 1: Genome Dataset Curation and Quality Control

Objective: To assemble a high-quality, non-redundant set of bacterial genomes with defined ecological niche labels for robust comparative analysis.

Materials:

- Computing Resources: High-performance computing cluster with sufficient storage.

- Software: CheckM, Mash, custom scripts for metadata parsing.

- Data Source: Public genome databases (e.g., gcPathogen) [7] [1].

Procedure:

- Initial Metadata Retrieval: Obtain metadata for a broad set of bacterial genomes (e.g., 1,166,418 pathogens from gcPathogen) [7].

- Source Annotation: Classify each genome into an ecological niche (Human, Animal, Environment) based on isolation source and host information from the metadata [7] [1].

- Stringent Quality Control:

- Retain only genomes with N50 ≥ 50,000 bp.

- Use CheckM to retain genomes with completeness ≥ 95% and contamination < 5%.

- Exclude genomes with unclear source information or those assembled only at the contig level [7].

- Redundancy Reduction:

- Calculate pairwise genomic distances using Mash.

- Perform Markov clustering to remove genomes with a distance ≤ 0.01, ensuring non-redundancy [7].

- Taxonomic Verification: Identify and exclude genomes where the assigned taxonomy conflicts with phylogenetic placement.

Expected Outcome: A refined, high-quality dataset of genomes (e.g., 4,366 genomes) labeled by ecological niche, ready for downstream analysis.

Protocol 2: Phylogenetic Analysis and Population Structure Delineation

Objective: To reconstruct the evolutionary relationships among genomes and define population clusters for controlled comparative genomics.

Materials:

- Software: AMPHORA2, Muscle v5.1, FastTree v2.1.11, R package

ape, R packagecluster. - Input: The 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome in the curated dataset.

Procedure:

- Marker Gene Extraction: Identify 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome using AMPHORA2 [7].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Align each marker gene independently using Muscle v5.1 [7].

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction:

- Concatenate the 31 individual alignments into a single super-alignment.

- Construct a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree using FastTree v2.1.11 [7].

- Population Clustering:

- Convert the phylogenetic tree into an evolutionary distance matrix using the R package

ape. - Perform k-medoids clustering using the

pamfunction in the Rclusterpackage. - Determine the optimal number of clusters (k) by calculating the average silhouette coefficient for k=1 to 10. Select the k value with the maximum coefficient (e.g., k=8) [7].

- Convert the phylogenetic tree into an evolutionary distance matrix using the R package

Expected Outcome: A robust phylogenetic tree and a set of defined population clusters. This allows for the comparison of genomic differences between bacteria from different niches within the same ancestral clade, controlling for phylogeny and strengthening associations.

Protocol 3: Functional Annotation of Adaptive Genes

Objective: To annotate virulence factors, CAZymes, antibiotic resistance genes, and general functional categories in the genomic dataset.

Materials:

- Software: Prokka, RPS-BLAST, dbCAN2, ABRicate.

- Databases: COG, CAZy, VFDB, CARD.

Procedure:

- Gene Prediction: Predict Open Reading Frames (ORFs) for all genomes using Prokka v1.14.6 [7].

- Functional Categorization (COG):

- Map predicted proteins to the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST (e-value threshold: 0.01, minimum coverage: 70%) [7].

- CAZyme Annotation:

- Annotate CAZymes using dbCAN2 by mapping ORFs to the CAZy database.

- Filter results using an HMMER e-value cutoff of 1e-5 [7].

- Virulence Factor Annotation:

- Antibiotic Resistance Gene Annotation:

- Identify ARGs by mapping genomes to the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) using ABRicate.

Expected Outcome: Comprehensive tables detailing the presence/absence and counts of COG categories, CAZyme families, VFs, and ARGs for each genome.

Protocol 4: Identification of Niche-Associated Signature Genes

Objective: To statistically identify genes significantly associated with a specific ecological niche.

Materials:

- Software: Scoary, Machine learning libraries (e.g., scikit-learn in Python).

- Input: Pan-genome file (from Roary or similar) and niche labels for each genome.

Procedure:

- Pan-genome Construction: Generate the pan-genome of the dataset, detailing the presence/absence of every gene across all genomes.

- Association Analysis: Use Scoary to perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Scoary will test for significant associations between each gene in the pan-genome and the predefined ecological niche labels [7].

- Machine Learning Validation:

- Use the pan-genome presence/absence matrix as features and niche labels as targets.

- Train a classifier (e.g., Random Forest) to predict niche membership.

- Extract feature importance metrics from the model to identify genes that are key predictors, thereby validating and complementing the Scoary results [7].

- Candidate Gene Investigation: Focus on genes with strong statistical support (e.g., from Scoary) and high feature importance (e.g., from machine learning), such as the hypB gene identified as a potential human host-specific signature [7].

Expected Outcome: A curated list of genes statistically associated with adaptation to human, animal, or environmental niches.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Genomic Analysis Workflow

Diagram 1: Genomic analysis workflow for signature adaptations.

Niche Adaptation Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Niche-specific adaptation mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Genomic Analysis of Bacterial Adaptations

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| CheckM | Software | Assesses genome quality (completeness/contamination) for QC [7]. |

| Mash | Software | Rapidly estimates genomic distance for dereplication [7]. |

| Prokka | Software | Rapidly annotates prokaryotic genomes and predicts ORFs [7]. |

| VFDB | Database | Central repository for curating and identifying bacterial virulence factors [8] [9]. |

| CAZy Database | Database | Classifies carbohydrate-active enzymes into families based on structure/mechanism [10] [11]. |

| CARD | Database | Provides curated reference of ARGs and their resistance mechanisms. |

| AMPHORA2 | Software/Pipeline | Identifies phylogenetic marker genes from genomes for robust tree building [7]. |

| FastTree | Software | Infers approximately-maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees from alignments [7]. |

| Scoary | Software | Performs pan-genome-wide association studies to link genes to traits/niches [7]. |

| dbCAN2 | Software/Pipeline | Automated CAZyme annotation tool using the CAZy database schema [7]. |

| ABRicate | Software | Mass-screens genomic data against resistance/virulence databases [7] [1]. |

The evolutionary arms race between bacterial pathogens and their hosts drives a process of continuous adaptation, leaving identifiable genetic signatures. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, two premier opportunistic pathogens, exemplify how bacteria undergo niche-specific genome degradation and convergent evolution to thrive in hostile host environments. Within the context of identifying niche-specific bacterial adaptive genes, this application note details standardized protocols for detecting, quantifying, and validating the genetic and phenotypic adaptations that underpin chronic and recurrent infections. The insights gained are critical for identifying novel therapeutic targets to combat multi-drug resistant infections.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of Adaptive Evolution

Key Adaptive Signatures inP. aeruginosaandS. aureus

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Adaptive Genetic Signatures in P. aeruginosa and S. aureus

| Feature | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Staphylococcus aureus |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Niches | Cystic Fibrosis (CF) lungs, nosocomial equipment, wounds [12] [13] | Anterior nares, skin, chronic wounds, diabetic foot ulcers [14] [15] [16] |

| Dominant Adaptive Mechanism | Horizontal gene acquisition & transcriptional regulation [12] | Genome degradation & convergent point mutations [16] |

| Key Adaptive Genes/Loci | dksA1 (stringent response), genes for inorganic ion transport & lipid metabolism [12] |

agr (quorum sensing), sucA, sucB, stp1 [16] |

| Phenotypic Consequence of Adaptation | Enhanced survival in CF macrophages, host-specific preference [12] | Immune evasion, antibiotic persistence, transition from colonization to invasion [15] [16] |

| Enrichment of Degradation Signals | Information Missing | Up to 20-fold enrichment in invasive vs. colonizing populations [16] |

| Convergent Evolution Evidence | Clones demonstrate varying intrinsic propensities for CF or non-CF individuals [12] | Significant, genome-wide convergent mutations in independent infection episodes [16] |

Protocol: Tracking Within-Host Bacterial Evolution via Whole-Genome Sequencing

Objective: To identify niche-specific adaptive mutations and genomic degradation signatures from serial bacterial isolates obtained during colonization and infection.

Materials & Reagents:

- Bacterial Isolates: Serial isolates from defined patient niches (e.g., nasal swab, sputum, blood, wound).

- DNA Extraction Kit: High-yield, high-purity genomic DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, Qiagen).

- Library Prep Kit: Illumina DNA Prep or Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit.

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq for short-read sequencing; Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION for long-read sequencing.

- Bioinformatics Software: Trimmomatic (adapter trimming), BWA (mapping), GATK (variant calling), Panaroo (pangenome analysis), Roary (pangenome pipeline).

Procedure:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Collect multiple bacterial isolates from different anatomical sites and time points. Extract genomic DNA and quantify using a fluorometer.

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries per manufacturer's protocol. Sequence to a minimum coverage of 100x. Include a reference strain for alignment.

- Variant Calling & Analysis:

- Quality Control: Trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases from raw reads.

- Mapping: Align reads to a reference genome.

- Variant Identification: Call single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (InDels) using a variant caller.

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Construct a phylogenetic tree from the core genome alignment to visualize the relatedness of serial isolates and identify evolutionary lineages.

- Convergence Testing: Scan the dataset for genes that accumulate non-synonymous mutations or loss-of-function mutations across independent evolutionary lineages at a rate significantly higher than the background mutation rate.

Host-Specific Adaptation and Intracellular Survival

Protocol: Assessing Bacterial Intracellular Survival in Macrophages

Objective: To quantify the ability of bacterial isolates from different epidemic clones to survive and replicate within wild-type and immunodeficient macrophages, modeling niche-specific immune evasion.

Materials & Reagents:

- Cell Lines: Wild-type THP-1 human monocyte cell line; isogenic CF model (e.g., F508del homozygous). [12]

- Cell Culture Media: RPMI-1640 with L-glutamine, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for THP-1 differentiation.

- Bacterial Strains: Isogenic bacterial strains with gene knockouts (e.g., P. aeruginosa ΔdksA1,2). [12]

- Antibiotics: Gentamicin, for killing extracellular bacteria.

- Lysis Buffer: Sterile Triton X-100 (0.1% in PBS).

- Assay Reagents: PBS, tissue culture-treated plates.

Procedure:

- Macrophage Differentiation: Culture THP-1 monocytes and differentiate into macrophages by treating with 100 nM PMA for 48 hours.

- Infection: Infect macrophages at a Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) of 10:1 (bacteria:macrophage). Centrifuge plates to synchronize infection.

- Extracellular Antibiotic Kill: After 2 hours of infection, replace the medium with fresh medium containing gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria.

- Intracellular Survival Quantification:

- At designated time points (e.g., 2, 6, 24 hours post-infection), wash cells with PBS and lyse with 0.1% Triton X-100.

- Serially dilute the lysates in PBS and plate on agar plates to enumerate viable Colony Forming Units (CFUs).

- Data Analysis: Calculate intracellular survival as the percentage of bacteria that survived relative to the initial inoculum. Compare survival rates between wild-type and mutant bacterial strains in different macrophage cell lines.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for the macrophage survival assay.

Bacterial Interaction and Co-Adaptation in Polymicrobial Infections

Protocol: Modeling Polymicrobial Biofilm Formation in Artificial Sputum

Objective: To establish a robust dual-species biofilm model that recapitulates the co-adaptation of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in the cystic fibrosis lung environment. [17]

Materials & Reagents:

- Artificial Sputum Medium (ASM): A synthetic medium mimicking the nutrient composition and viscosity of CF sputum, containing mucin, DNA, amino acids, and salts. [17]

- Bacterial Strains: Clinical co-isolates of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus from the same patient. [17]

- Culture Vessels: 96-well polystyrene plates or Calgary biofilm pins.

- Staining Reagents: Crystal violet solution (0.1%) for total biomass, SYTO 9/propidium iodide for viability staining.

- Equipment: Microplate reader, confocal microscope.

Procedure:

- Inoculation: Pre-inoculate wells with S. aureus suspended in ASM and incubate for 24 hours to allow initial attachment. [17]

- Co-culture Introduction: Inoculate P. aeruginosa into the pre-established S. aureus culture.

- Biofilm Growth: Incubate the co-culture under static conditions for 48-96 hours to allow for mature biofilm development.

- Biofilm Quantification:

- Total Biomass: Wash, fix, and stain biofilms with crystal violet. Elute the dye and measure absorbance.

- Viable Counts: Dislodge biofilms by sonication/vortexing, then perform serial dilution and plating on selective media to count CFUs for each species.

- Confocal Microscopy: Image live/dead stained biofilms to visualize the 3D structure and spatial organization.

- Analysis: Compare the stability and biomass of biofilms formed by co-isolates versus randomly paired isolates to infer cross-adaptation.

The following diagram visualizes the signaling and interaction network between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Bacterial Adaptation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Sputum Medium (ASM) | Mimics the nutrient and physicochemical environment of the CF lung for in vitro culture. [17] | Polymicrobial biofilm models of CF lung co-infections. [17] |

| THP-1 Human Monocyte Cell Line | A model cell line that can be differentiated into macrophages for studying intracellular bacterial survival. [12] | Assessing the role of P. aeruginosa dksA1 in surviving within CF macrophages. [12] |

| Isogenic Mutant Strains (e.g., ΔdksA1,2) | Genetically engineered strains to determine the specific function of a gene in pathogenesis and adaptation. [12] | Validating the role of stringent response mediators in macrophage survival and immune evasion. [12] |

| Pan-Genome Analysis Software (Panaroo) | Infers a pan-genome graph from sequence data to analyze core and accessory genome content. [12] | Identifying horizontally acquired genes enriched in epidemic clones. [12] |

| Selective Culture Media | Allows for the quantitative discrimination and enumeration of different bacterial species from a polymicrobial culture. [17] | Quantifying the proportion of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in a dual-species biofilm. [17] |

From Data to Discovery: Bioinformatics Workflows for Gene Identification

Genome Quality Control and Phylogenetic Framework Construction

In the field of bacterial genomics, the identification of niche-specific adaptive genes relies on two foundational pillars: the generation of high-quality, comparable whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data and the construction of accurate phylogenetic frameworks. Genomic data quality directly impacts the reliability of downstream comparative analyses, while robust phylogenies provide the evolutionary context necessary to distinguish true adaptive signatures from random genetic variation. The exponential growth of global genomic initiatives has highlighted a critical challenge: variability in data production processes and inconsistent implementation of quality control metrics hinder the comparison, integration, and reuse of WGS datasets across institutions [18]. Overcoming these barriers is essential for research aimed at understanding how bacterial pathogens evolve under niche-specific selection pressures, which can ultimately inform targeted treatment strategies and antibiotic stewardship [1].

This application note provides detailed protocols for performing rigorous quality control of whole-genome sequencing data and constructing phylogenetic trees, specifically framed within research investigating niche-specific bacterial adaptation. The methodologies are designed to enable researchers to detect genetic signatures of adaptation, such as convergent evolution and genome degradation, which occur as bacteria transition between different host and environmental niches [16].

Whole-Genome Sequencing Quality Control Standards and Protocols

Core QC Standards and Metrics

The Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) has established a unified framework for assessing the quality of short-read germline WGS data through its WGS Quality Control (QC) Standards [18]. These standards provide a structured set of formally defined QC metrics, reference implementations, and usage guidelines to ensure consistent, reliable, and comparable genomic data quality across institutions. Implementation of these standards improves interoperability, reduces redundant effort, and increases confidence in the integrity and comparability of WGS data, which is fundamental for cross-study analysis of niche adaptation [18].

Table 1: Core Components of the GA4GH WGS QC Standards

| Component | Description | Primary Function in Niche Adaptation Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized QC Metric Definitions | Unified definitions for metadata, schema, and file formats. | Enables shareability and reduces ambiguity in cross-institutional datasets. |

| Reference Implementation | Flexible and scalable example QC workflow. | Demonstrates practical application of the standards for diverse bacterial genomes. |

| Benchmarking Resources | Standardized unit tests and benchmarking datasets. | Validates implementations and assesses computational resources for large-scale analyses. |

Detailed QC Experimental Protocol

The following protocol outlines key quality control steps, from nucleic acid extraction to sequencing data assessment, adapted for bacterial genomics studies.

Pre-Sequencing QC: Sample and Library Preparation

Procedure:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction and Assessment:

- Extract genomic DNA from bacterial cultures or directly from environmental/clinical samples using standardized kits.

- Quantification and Purity: Measure DNA concentration using a fluorescence dye-based method (e.g., Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit). Assess purity spectrophotometrically (e.g., NanoDrop). A260/A280 ratios of ~1.8 are generally indicative of pure DNA [19].

- Integrity: Analyze DNA integrity using electrophoresis systems (e.g., Agilent TapeStation or Fragment Analyzer) to ensure high molecular weight DNA is present [20] [19].

- Library Preparation and QC:

- Fragment genomic DNA to an average target size (e.g., 550 bp) using a focused-ultrasonicator (e.g., Covaris LE220) [20].

- Prepare sequencing libraries using PCR-free kits (e.g., TruSeq DNA PCR-free HT or MGIEasy PCR-Free DNA Library Prep Set) to avoid amplification bias [20].

- Library QC: Measure final library concentration (e.g., with Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit) and analyze size distribution (e.g., with Fragment Analyzer or TapeStation) [20].

Post-Sequencing QC: Raw Data Assessment and Processing

Procedure:

- Initial Data Quality Assessment:

- Sequencing instruments typically produce raw data in FASTQ format. Use quality control tools like FastQC to generate an initial report on key metrics [19].

- Critically examine the "per base sequence quality" graph. Quality scores (Q scores) above 20 are generally acceptable, with scores >30 indicating high quality. A decrease in quality towards the 3' end of reads is common and should be noted for trimming [19].

- For Illumina platforms, monitor run-specific metrics such as % Clusters Passing Filter (% PF, target >80%) and low phasing/prephasing values [20] [19].

Read Trimming and Filtering:

- Use tools like CutAdapt or Trimmomatic to perform adapter removal and quality trimming [19].

- Set a quality threshold (e.g., Q20) to trim low-quality bases from the 3' end. Subsequently, filter out reads that fall below a minimum length (e.g., 20 bases) after trimming [19].

- For long-read data from platforms like Oxford Nanopore Technologies, use specialized tools like NanoPlot for quality assessment and Chopper or Porechop for filtering and adapter removal [19].

Alignment and Variant Calling QC (for Reference-Based Analyses):

- Align trimmed reads to a reference genome using aligners such as BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) [20].

- Process aligned BAM files according to best practices (e.g., GATK-based pipelines for eukaryotes). For bacterial studies, use specialized variant callers and perform filtration based on quality scores [20] [21].

- Sample Identity Verification: If applicable, confirm sample integrity by assessing genotype-level concordance with other data types (e.g., SNP arrays) to detect sample mix-ups [20].

Table 2: Key QC Metrics and Target Values for Bacterial WGS

| QC Step | Metric | Target / Acceptable Value | Tool/Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Quality | A260/A280 Ratio | ~1.8 | NanoDrop |

| DNA Integrity | High Molecular Weight | TapeStation/Fragment Analyzer | |

| Library Quality | Size Distribution | Tight peak around expected size (e.g., 550 bp) | TapeStation/Fragment Analyzer |

| Sequencing Run | Q Score | >30 (Excellent), >20 (Acceptable) | FastQC |

| % Clusters Passing Filter | >80% | Illumina SAV | |

| Raw Data | Adapter Content | 0% after trimming | FastQC, CutAdapt |

| GC Content | Consistent with organism | FastQC | |

| Alignment | Mean Coverage | >50x for variant calling | Picard, SAMtools |

| Duplication Rate | As low as possible | Picard, SAMtools |

Phylogenetic Framework Construction for Bacterial Genomics

A phylogenetic tree is a graphical representation of the evolutionary relationships between biological taxa, comprising nodes (representing taxonomic units) and branches (depicting evolutionary relationships and time) [22]. Constructing a robust phylogenetic tree is essential for placing bacterial isolates within an evolutionary context, which allows researchers to identify lineage-specific mutations and distinguish them from convergent, niche-specific adaptive signatures [16] [23].

Table 3: Common Methods for Phylogenetic Tree Construction

| Algorithm | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Scope of Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbor-Joining (NJ) | Distance-based minimal evolution. | Fast computation; suitable for large datasets. | Loss of sequence information; produces a single tree. | Short sequences with small evolutionary distance [22]. |

| Maximum Parsimony (MP) | Minimizes the number of evolutionary steps. | Straightforward; no explicit model required. | Can be inaccurate with distant sequences; many equally parsimonious trees. | Sequences with high similarity [22]. |

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) | Maximizes the probability of the data given a tree and evolutionary model. | Highly accurate; uses all sequence data. | Computationally intensive. | Distantly related sequences [22]. |

| Bayesian Inference (BI) | Uses Bayes' theorem to estimate the posterior probability of trees. | Provides branch support probabilities. | Extremely computationally intensive. | Small number of sequences [22]. |

Detailed Protocol: Constructing a Phylogenetic Tree from Bacterial Genomes

This protocol describes a standard workflow for building a phylogenetic tree from a set of bacterial genome sequences, which can be applied to study the relatedness of isolates from different ecological niches.

Procedure:

- Sequence Collection and Dataset Curation:

- Collect whole-genome sequences (assembled genomes or raw reads) from public databases (e.g., GenBank) or in-house sequencing projects.

- Implement stringent quality control as described in Section 2. Ensure genomes are non-redundant and have high completeness (≥95%) and low contamination (<5%) [1].

- Annotate genomes with ecological niche labels (e.g., human, animal, environment) based on isolation source metadata for downstream comparative analysis [1].

Identification of Marker Genes or Core Genomes:

- For a multi-locus approach: Identify a set of universal single-copy marker genes. Tools like AMPHORA2 can be used to automatically retrieve a defined set of these genes (e.g., 31 genes) from each genome [1].

- For a genome-wide approach: Calculate the pan-genome (the full repertoire of genes) and identify the core genome (genes shared by all isolates under study) using tools like Roary or Panaroo. The core genome can be used for high-resolution phylogeny [23].

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA):

- For each marker gene or core gene, perform a multiple sequence alignment using tools such as Muscle or MAFFT [1] [22].

- Concatenate the individual gene alignments into a single, supermatrix alignment for phylogenetic inference [1].

- Precisely trim the aligned sequences to remove unreliable regions that may introduce noise into the phylogenetic analysis [22].

Model Selection and Tree Inference:

- Select the best-fit model of nucleotide or amino acid substitution using tools like ModelTest or ProtTest. This step is crucial for model-based methods like ML and BI [22].

- Construct the phylogenetic tree using your chosen method. For large datasets, the Neighbor-Joining method in FastTree offers a good balance of speed and accuracy. For higher accuracy, use Maximum Likelihood with RAxML or IQ-TREE [1] [22].

- Assess branch support using bootstrapping (e.g., 1000 replicates) to evaluate the confidence of the inferred topological splits [22].

Tree Visualization and Interpretation:

- Visualize and annotate the final tree using tools like iTOL (Interactive Tree Of Life), which allows coloration of tips or clades based on ecological niche metadata (e.g., human-associated vs. environmental) to visually identify potential niche-specific clustering [1].

Advanced and Emerging Methods

Leveraging Pan-Genome Analysis: The analysis of pan-genomes at different taxonomic levels (species, genus) helps delineate the relative importance of lineage-specific versus niche-specific genes, revealing adaptive functions in the flexible genome [23].

PhyloTune for Efficient Updates: For integrating new bacterial sequences into an existing large tree, the PhyloTune method uses a pre-trained DNA language model to identify the taxonomic unit of a new sequence and extracts high-attention regions for subtree construction, significantly accelerating phylogenetic updates without manual marker selection [24].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic QC and Phylogenetics

| Item / Resource | Function | Example Products / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction & QC | Isolates high-quality genomic DNA from bacterial samples. | Qiagen Autopure LS, GENE PREP STAR NA-480, Oragene (saliva), NanoDrop, Agilent TapeStation [20]. |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepares DNA fragments for sequencing by adding platform-specific adapters. | TruSeq DNA PCR-free HT (Illumina), MGIEasy PCR-Free DNA Library Prep Set (MGI) [20]. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Generates raw sequence reads (FASTQ files). | Illumina (NovaSeq X Plus), MGI (DNBSEQ-T7), Oxford Nanopore [20] [19]. |

| QC Analysis Software | Assesses quality of raw sequencing data and identifies contaminants/adapters. | FastQC, CutAdapt, Trimmomatic, NanoPlot (for long reads) [20] [19]. |

| Alignment & Assembly Tools | Maps reads to a reference genome or performs de novo assembly. | BWA, BWA-mem2, SPAdes, Flye [20]. |

| Variant Caller | Identifies single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (Indels). | GATK HaplotypeCaller (best practices), Snippy [20] [21]. |

| Phylogenetic Software | Constructs and visualizes evolutionary trees from sequence alignments. | FastTree (NJ/ML), RAxML-NG (ML), IQ-TREE (ML), AMPHORA2 (marker gene ID), MAFFT (alignment), iTOL (visualization) [1] [22] [24]. |

| Pan-Genome Analysis Tools | Computes the core and flexible genome of a set of bacterial isolates. | Roary, Panaroo [23]. |

Application in Niche Adaptation Research: From Data to Discovery

The integration of rigorous QC and robust phylogenetic frameworks directly enables the identification of niche-specific adaptive genes. For instance, in a large-scale study of Staphylococcus aureus, researchers performed within-host evolution analysis on 2,590 genomes from 396 independent infection episodes. By constructing a phylogenetic framework and comparing invasive versus colonizing populations, they identified significantly convergent mutations in genes linked to antibiotic response and pathogenesis, which were enriched during severe infection [16]. Similarly, a comparative genomic analysis of 4,366 bacterial genomes from different hosts and environments utilized phylogenetic clustering (k=8 medoids based on an evolutionary distance matrix) to compare genomic differences within the same ancestral clade. This approach revealed that human-associated bacteria exhibited higher counts of virulence factors, while environmental isolates showed greater enrichment of metabolic genes, directly linking genetic content to ecological niche [1].

These case studies demonstrate that the consistent application of the QC and phylogenetic protocols outlined in this document is not merely a preparatory step but the foundation for reliable discovery. They allow researchers to move beyond simple correlation to confidently identify the genetic underpinnings of bacterial adaptation, providing valuable targets for future therapeutic interventions.

The identification of niche-specific bacterial adaptive genes is fundamental to understanding microbial evolution, pathogenesis, and ecological specialization. This research requires sophisticated bioinformatic resources that can accurately annotate gene functions and associate them with specific bacterial lifestyles and survival strategies. Four specialized databases have become indispensable for this purpose: the Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG), the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB), the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), and the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database (CAZy). Each database provides unique insights into different aspects of bacterial adaptation, from general cellular functions to specialized mechanisms for infection, antibiotic resistance, and carbohydrate metabolism.

The effective application of these databases enables researchers to move beyond simple genomic annotation to identify the genetic determinants that allow bacteria to colonize specific environments, evade host defenses, and develop resistance to antimicrobial agents. When integrated into a comprehensive analytical workflow, these resources facilitate the identification of niche-specific adaptive genes across clinical, environmental, and industrial contexts. This application note provides detailed protocols and comparative analyses to guide researchers in leveraging these databases for identifying bacterial adaptive genes, with particular emphasis on their application in drug development and microbial ecology research.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Specialized Bacterial Genomics Databases

| Database | Primary Focus | Latest Version | Key Features | Update Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG | Orthologous gene groups & core cellular functions | 2024 | 4,981 COGs covering 2,296 prokaryotic genomes; Functional classification system | Regular updates |

| VFDB | Bacterial virulence factors | 2025 | 902 anti-virulence compounds; 62,332 non-redundant VF orthologues/alleles | Annual |

| CARD | Antibiotic resistance genes & mechanisms | Ongoing | Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO); 8,582 ontology terms; 6,480 AMR detection models | Continuous curation |

| CAZy | Carbohydrate-active enzymes | October 2025 | 2 novel families (CBM107, GT139); CAZac reaction descriptors; 7,198 characterized GHs | Monthly updates |

Database-Specific Analytical Protocols

Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) Protocol

The CARD database employs a sophisticated ontology-driven framework for identifying antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and their mechanisms. The database's core organizing principle is the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO), which systematically classifies resistance determinants, mechanisms, and antibiotic molecules [25] [26]. This structured approach enables precise annotation of resistance genes and prediction of resistance phenotypes from genomic data.

Experimental Protocol: Resistance Gene Identification Using CARD

- Data Preparation: Prepare assembled bacterial genomes or metagenomic contigs in FASTA format. For raw read analysis, ensure quality control and adapter trimming have been performed.

- Tool Selection: Utilize the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) software, available as both a web interface and command-line tool [25].

- Analysis Execution:

- For web interface: Upload sequences to the RGI online platform and select appropriate parameters.

- For local analysis: Run

rgi main -i input_file -o output_file -t contigfor assembled sequences.

- Result Interpretation: Analyze output files for ARO terms, which provide detailed information on resistance mechanisms, drug classes, and associated evidence.

- Validation: Cross-reference significant findings with the "Strict" criterion model, which requires experimental evidence for resistance confirmation [26].

The CARD database includes multiple specialized modules beyond its core resistance gene catalog. The "Resistomes & Variants" database contains in silico-validated ARGs derived from sequences stored in CARD, extending the range of ARGs available for computational analyses [26]. Recent expansions include FungAMR for fungal antimicrobial resistance and TB Mutations for Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance-conferring mutations [25]. For comprehensive resistome analysis, researchers can leverage CARD's bait capture platform for targeted enrichment of resistance determinants in complex samples [25].

Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) Protocol

VFDB has evolved from a simple virulence factor catalog to an integrated resource that now includes information on anti-virulence compounds, providing valuable references for drug design and repurposing [27]. The database's expansion to include 62,332 non-redundant orthologues and alleles of virulence factor genes (VFGs) enables more comprehensive profiling of bacterial pathogenicity [28].

Experimental Protocol: Virulence Factor Annotation Using VFDB 2.0 and MetaVF Toolkit

- Database Selection: Download the expanded VFDB 2.0 alignment dataset, which includes VFG sequences from 135 bacterial species corresponding to 3,527 types of VFGs [28].

- Sequence Alignment:

- For short-read metagenomic data: Map clean reads against the expanded alignment dataset to obtain VFG-mapped reads.

- For long HiFi reads or MAGs: Perform nucleotide BLAST against the pathogenic alignment dataset.

- Quality Filtering: Apply the tested sequence identity (TSI) threshold of 90% to minimize false positives while maintaining a true discovery rate >97% [28].

- Normalization and Annotation: Normalize filtered VFG-mapped reads by gene length and sequencing depth, represented by transcripts per million (TPM). Annotate VFG clusters, mobility, bacterial host taxonomy, and virulence factor categories according to the annotation dataset.

- Comparative Analysis: Identify shared and unique VFG patterns across samples or conditions, noting particularly the presence of mobile genetic elements associated with virulence genes.

The MetaVF toolkit demonstrates superior sensitivity and precision compared to previous tools like PathoFact and ShortBRED, particularly for datasets with higher mutation rates [28]. This enhanced performance makes it particularly valuable for identifying emerging virulence factors that may deviate from canonical sequences.

Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database (CAZy) Protocol

CAZy provides a classification system for enzymes that build and break down complex carbohydrates, which are crucial for bacterial adaptation to specific ecological niches, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract and plant-associated environments [29] [10]. The database organizes enzymes into families based on amino acid sequence similarities and mechanistic features.

Experimental Protocol: CAZyme Annotation and Functional Prediction

- Sequence Annotation:

- Option A (CAZy Web Service): Submit sequences for automatic annotation or request human curation services via cazy@univ-amu.fr for higher-quality analysis [10].

- Option B (ez-CAZy): For specialized glycoside hydrolase (GH) annotation, use the ez-CAZy database, which links GH sequences to enzymatic activities using Hidden Markov Model profiles [29].

- Domain Architecture Analysis: Identify catalytic domains and associated carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) using Pfam HMM profiles or other domain prediction tools.

- Functional Prediction: Move beyond the "majority rule" approach by:

- Subfamily Classification: For polyspecific families (e.g., GH5), implement subfamily classification systems (e.g., GH5_7) to improve functional prediction accuracy.

The ez-CAZy database addresses a critical gap in CAZyme annotation by providing explicit sequence-activity relationships, moving beyond the potentially misleading "majority rule" approach that assumes newly identified sequences share the dominant activity in their family [29]. This is particularly important for polyspecific CAZy families where multiple activities are represented.

Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) Protocol

The COG database provides a phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes, enabling functional annotation and evolutionary analysis of bacterial genes [30]. The 2024 update expanded the database to include 2,296 prokaryotic genomes (2,103 bacteria and 193 archaea), with nearly one representative genome per genus, significantly improving coverage of microbial diversity [30].

Experimental Protocol: Functional Annotation Using COG

- Data Input: Prepare protein sequences from completely sequenced bacterial genomes in FASTA format.

- COG Assignment:

- Use the web interface at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/COG/ for individual sequences or small datasets.

- For large-scale analyses, download the COG database from the NCBI FTP site and perform local analyses using BLAST or similar tools.

- Functional Categorization: Classify identified COGs into functional categories (e.g., metabolism, cellular processes, information storage and processing).

- Comparative Genomics: Identify conserved COGs across related species (core genome) and species-specific COGs (accessory genome) to pinpoint potential adaptive genes.

- Pathway Analysis: Utilize updated COG pathways, including newly added bacterial secretion systems (types II through X, Flp/Tad, and type IV pili), to identify functional systems associated with specific niches.

Table 2: Database-Specific Tools and Analytical Outputs

| Database | Primary Tool | Key Outputs | Strength in Adaptive Gene Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| CARD | Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) | ARO terms, resistance mechanisms, drug classes | Comprehensive antibiotic resistance profiling |

| VFDB | MetaVF toolkit | VFG abundance, mobility, bacterial host taxonomy | Pathogen and pathobiont virulence potential |

| CAZy | ez-CAZy, HMMER | CAZy family assignment, domain architecture, EC numbers | Carbohydrate utilization capabilities |

| COG | COGnitor, Web BLAST | Functional categories, orthologous groups | Core cellular functions and evolutionary relationships |

Integrated Workflow for Identifying Niche-Specific Adaptive Genes

The true power of these specialized databases emerges when they are integrated into a comprehensive analytical workflow for identifying niche-specific bacterial adaptive genes. This integrated approach allows researchers to move from gene identification to functional interpretation and hypothesis generation about bacterial adaptation mechanisms.

Diagram: Integrated workflow for identifying niche-specific adaptive genes using specialized databases

Implementation of the Integrated Workflow

The integrated workflow begins with quality-controlled genomic or metagenomic sequences, which are simultaneously analyzed using the four specialized databases. Parallel analysis ensures consistent input data and facilitates downstream integration. The specific analytical approaches for each database follow the protocols outlined in Section 2.

Following individual analyses, the results are integrated to identify genes that contribute to niche-specific adaptations. This integration can be achieved through:

- Comparative Genomics: Identify genes present in niche-specific strains but absent in related strains from different environments.

- Correlation Analysis: Associate gene presence/absence or abundance with specific environmental parameters or host conditions.

- Network Analysis: Construct functional networks linking adaptive genes to specific metabolic pathways or phenotypic traits.

- Machine Learning: Implement algorithms like the random forest approach used in bacLIFE to identify genes predictive of specific lifestyles [31].

The bacLIFE computational workflow exemplifies this integrated approach, successfully identifying hundreds of genes associated with phytopathogenic lifestyles in Burkholderia and Pseudomonas genera through comparative genomics and machine learning [31]. This tool demonstrates how combining database annotations with advanced analytical methods can pinpoint previously unknown adaptive genes.

Validation of Predicted Adaptive Genes

Computational predictions of adaptive genes require experimental validation to confirm their functional roles. The bacLIFE study provides an excellent model for this validation process, where site-directed mutagenesis of 14 predicted lifestyle-associated genes (LAGs) of unknown function followed by plant bioassays confirmed that 6 were indeed involved in phytopathogenic lifestyle [31]. These validated LAGs included a glycosyltransferase, extracellular binding proteins, homoserine dehydrogenases, and hypothetical proteins.

Similar validation approaches can be applied to genes identified through the integrated database workflow:

- Genetic Manipulation: Knock out or knock down candidate adaptive genes in model bacterial strains.

- Phenotypic Assays: Assess the impact of genetic manipulation on niche-relevant phenotypes (e.g., colonization efficiency, antibiotic resistance, substrate utilization).

- Expression Analysis: Measure gene expression under niche-specific conditions using RT-qPCR or transcriptomics.

- Complementation Studies: Restore gene function to confirm phenotype-genotype relationships.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Adaptive Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RGI Software | Predicts antibiotic resistance genes from sequence data | CARD database analysis [25] |

| MetaVF Toolkit | Profiles virulence factor genes from metagenomic data | VFDB analysis with superior sensitivity/precision [28] |

| ez-CAZy Database | Links glycoside hydrolase sequences to enzymatic activities | CAZy annotation with improved functional prediction [29] |

| bacLIFE Workflow | Identifies lifestyle-associated genes through comparative genomics | Integrated analysis of bacterial adaptation [31] |

| AntiSMASH | Identifies biosynthetic gene clusters | Secondary metabolite discovery in niche adaptation |

| Oxford Nanopore Sequencing | Long-read sequencing technology | Complete genome assembly for accurate gene context [32] |

Applications in Drug Development and Microbial Ecology

The identification of niche-specific adaptive genes through specialized databases has profound implications for drug development and microbial ecology research. In pharmaceutical applications, this approach enables targeted development of antimicrobial therapies that specifically disrupt pathogenic adaptations without affecting commensal microbiota.

For antibiotic development, CARD facilitates the identification of resistance mechanisms that can be targeted with novel inhibitors or bypassed through drug design [26]. Similarly, VFDB's integration of anti-virulence compound information provides a resource for developing therapeutics that disarm pathogens without exerting strong selective pressure for resistance [27]. The database currently includes 902 anti-virulence compounds across 17 superclasses reported by 262 studies worldwide, offering valuable starting points for drug discovery programs [27].

In microbial ecology, the integration of CAZy and COG analyses helps elucidate how bacteria adapt to specific ecological niches through carbohydrate utilization and metabolic specialization. This is particularly relevant for understanding plant-microbe interactions, gut microbiome ecology, and biogeochemical cycling. The application of ez-CAZy to link GH sequences to specific enzymatic activities enables more accurate prediction of bacterial roles in carbohydrate degradation in various ecosystems [29].

The bacLIFE workflow demonstrates how these databases can be leveraged to understand the genetic basis of bacterial lifestyles, successfully discriminating between environmental, pathogenic, and plant-beneficial strains in the Burkholderia and Pseudomonas genera [31]. This approach can be extended to other bacterial groups with diverse lifestyles, providing insights into the evolutionary transitions between commensal, mutualistic, and pathogenic states.

Specialized databases including COG, VFDB, CARD, and CAZy provide indispensable resources for identifying niche-specific bacterial adaptive genes. When employed individually following the detailed protocols outlined in this application note, each database offers unique insights into specific aspects of bacterial adaptation. However, their true power emerges when integrated into a comprehensive analytical workflow that combines their complementary strengths.

The rapidly evolving nature of these databases—with recent updates expanding their scope and improving their accuracy—ensures they remain at the forefront of bacterial genomics research. Researchers are encouraged to monitor updates such as COG's expanded genome coverage, VFDB's inclusion of anti-virulence compounds, CARD's new modules for fungal and TB resistance, and CAZy's continuous addition of novel families and functional descriptors.

By implementing the integrated approaches and validation strategies described in this application note, researchers can accelerate the discovery of bacterial adaptive genes, advancing both fundamental understanding of microbial ecology and the development of novel therapeutic interventions against pathogenic bacteria.

Comparative Genomics and Pan-Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

Application Notes: Uncovering Niche-Specific Bacterial Adaptations

Core Concepts and Relevance

Comparative genomics serves as a foundational approach for deciphering the genetic basis of bacterial adaptation to specific ecological niches. By analyzing and comparing genomic features across multiple bacterial strains, researchers can identify signature genes and evolutionary mechanisms that enable pathogens to colonize particular hosts and environments [33]. Pan-genome-wide association studies (Pan-GWAS) extend this approach by systematically linking genetic variations within the entire gene repertoire of a bacterial species (the pan-genome) to specific adaptive traits or niche specializations [7]. This integrated framework is particularly powerful for investigating how bacterial pathogens evolve distinct life history strategies across different habitats.

The exponential growth of genomic databases has dramatically accelerated these research avenues. The Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB), for instance, expanded from 402,709 bacterial and archaeal genomes in April 2023 to 732,475 genomes by April 2025 [33]. This wealth of data provides unprecedented resolution for identifying even subtle genomic differences associated with niche adaptation.

Key Findings in Niche Adaptation Research

Recent comparative genomic studies have revealed distinct adaptive strategies employed by bacterial pathogens from different phyla when colonizing human hosts:

- Gene Acquisition in Pseudomonadota: Human-associated bacteria from this phylum exhibit higher counts of carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZy) genes and virulence factors related to immune modulation and adhesion, indicating a strategy of acquiring beneficial genes through horizontal gene transfer [7].

- Genome Reduction in Actinomycetota and Bacillota: In contrast, these taxa often show evidence of reductive evolution, streamlining their genomes to eliminate unnecessary functions and reallocate resources toward maintaining mutualistic relationships with their hosts [7].

- Antibiotic Resistance Reservoirs: Bacteria isolated from clinical settings consistently show higher detection rates of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), particularly those conferring fluoroquinolone resistance. Furthermore, animal hosts have been identified as significant reservoirs of novel virulence and resistance genes, highlighting their role in the One Health paradigm [7].

Table 1: Niche-Specific Genomic Features Identified Through Comparative Genomics

| Ecological Niche | Enriched Genomic Features | Example Adaptive Genes | Proposed Adaptive Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Host | High CAZy genes, immune evasion factors, adhesion virulence factors | hypB | Potential role in regulating metabolism and immune adaptation [7] |

| Animal Host | Reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes, host-specific virulence factors | Lactose metabolism genes in bovine S. aureus | Adaptation to dairy cattle environment [7] |

| Clinical Environment | Fluoroquinolone resistance genes, multidrug efflux pumps | Genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Transition from environmental to human host [7] |

| Soil/Rhizosphere | Metabolic and transcriptional regulation genes, secondary metabolite clusters | Streptomyces enrichment in spinach roots [34] | Plant-microbe interactions and health promotion [34] |

Protocols for Identifying Niche-Specific Adaptive Genes

Protocol 1: Genome Collection and Phylogenetic Framework

Objective: To assemble a high-quality, non-redundant set of bacterial genomes and establish a robust phylogenetic framework for comparative analysis [7].

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

Data Retrieval and Quality Control:

- Source initial genome metadata from specialized databases such as gcPathogen [7].

- Implement stringent quality filters: retain only chromosome- or scaffold-level assemblies with N50 ≥ 50,000 bp.

- Assess genome quality using CheckM, requiring ≥ 95% completeness and < 5% contamination [7].

- Annotate each genome with an ecological niche label (e.g., Human, Animal, Environment) based on isolation source metadata [7].

Phylogenetic Analysis:

- Extract 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome using AMPHORA2 [7].

- Perform multiple sequence alignment for each marker gene with Muscle v5.1 [7].

- Concatenate alignments and construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using FastTree v2.1.11 [7].

- Convert the phylogenetic tree into an evolutionary distance matrix using the R package

ape. Perform k-medoids clustering (using thepamfunction in R) to define phylogenetically related groups for downstream comparative analysis. Determine the optimal cluster number (k) by calculating the average silhouette coefficient [7].

Protocol 2: Pan-GWAS for Identification of Adaptive Genes

Objective: To statistically associate gene presence/absence patterns in the bacterial pan-genome with specific ecological niches, controlling for phylogenetic relatedness.

Experimental Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

Functional Annotation and Pan-Genome Construction:

- Predict Open Reading Frames (ORFs) for each genome using Prokka v1.14.6 [7].

- Construct the pan-genome using a tool like Roary, which identifies core (shared by all) and accessory (variable) genes across the genome set [33].

- Generate a gene presence/absence binary matrix capturing the repertoire of every gene in each strain.

Association Testing:

- Use the Scoary algorithm to perform association testing between each gene in the pan-genome and the ecological niche labels [7].

- Incorporate the phylogenetic tree or cluster information from Protocol 1 to account for population structure and avoid spurious associations.

- Apply strict multiple testing correction (e.g., Bonferroni or Benjamini-Hochberg) to identify statistically significant gene-niche associations.

Validation with Machine Learning:

- Employ machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest) using the gene presence/absence matrix to predict the ecological niche [7].

- Use feature importance scores from the model to cross-validate and prioritize genes identified by the Pan-GWAS, enhancing the robustness of candidate adaptive genes.

Protocol 3: Functional Characterization of Adaptive Genes

Objective: To infer the biological functions and potential mechanistic roles of candidate niche-specific adaptive genes.

Detailed Methodology:

Database-Driven Functional Annotation:

- COG Annotation: Map ORFs to the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST (e-value threshold 0.01, minimum coverage 70%) for broad functional categorization [7].

- Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes: Annotate CAZy genes using dbCAN2 and the HMMER tool (hmm_eval 1e-5) to understand dietary adaptation capabilities [7].

- Virulence and Pathogenicity: Query the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) to identify genes involved in host colonization, immune evasion, and toxicity [7].

- Antibiotic Resistance: Screen for known resistance determinants against the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) to assess the potential for antimicrobial resistance [33] [7].

Comparative Functional Enrichment Analysis:

- For each niche of interest (e.g., human, animal), test for the significant over-representation of specific COG categories, CAZy families, virulence factors, or resistance genes compared to genomes from other niches.

- Perform statistical tests (e.g., Fisher's exact test) followed by multiple testing correction to identify functions strongly associated with a particular niche.

Table 2: Key Databases for Functional Annotation of Bacterial Genomes

| Database Name | Primary Function | Application in Niche Adaptation Research |

|---|---|---|

| COG Database | Functional categorization of genes based on orthology | Identifying enriched biological processes (e.g., metabolism, transcription) in a niche [7] |

| CAZy Database | Catalog of carbohydrate-active enzymes | Inferring adaptation to host dietary polysaccharides [7] |

| Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) | Repository of bacterial virulence factors | Uncovering mechanisms for host colonization and immune system interaction [7] |

| Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | Collection of known antibiotic resistance genes and mechanisms | Assessing resistance potential and its spread in specific environments (clinics, farms) [33] [7] |

| Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) | Standardized microbial taxonomy based on genomics | Ensuring accurate phylogenetic placement of genomes for comparative analysis [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Reagents for Comparative Genomics and Pan-GWAS

| Item/Tool Name | Type | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit | Wet-lab reagent | Standardized DNA extraction from complex samples (e.g., soil, rhizosphere) for high-quality sequencing [34] |

| CheckM | Bioinformatics tool | Assesses genome quality (completeness, contamination) prior to analysis [7] |

| Prokka | Bioinformatics tool | Rapid annotation of prokaryotic genomes, generating standardized GFF files for downstream analysis [7] |

| Roary | Bioinformatics tool | Pan-genome pipeline construction from annotated genomes, generating core gene alignment and presence/absence matrix [33] |

| Scoary | Bioinformatics tool | Pan-GWAS tool that identifies trait-associated genes from pan-genome data while correcting for population structure [7] |

| dbCAN2 | Web server / Tool | Annotation of carbohydrate-active enzymes in genomic or metagenomic data [7] |

| FastTree | Bioinformatics tool | Efficiently approximates maximum-likelihood phylogenies for large alignments of core genes [7] |

| R microeco package | R package | Provides a pipeline for statistical analysis and visualization of microbiome data, integrating with other omics data types [35] |