Comparative Genomic Analysis of Bacterial Pathogens: Unveiling Evolution, Resistance, and Precision Targets

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of comparative genomic methodologies and their pivotal role in deciphering the evolution, adaptation, and antimicrobial resistance of bacterial pathogens.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of Bacterial Pathogens: Unveiling Evolution, Resistance, and Precision Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of comparative genomic methodologies and their pivotal role in deciphering the evolution, adaptation, and antimicrobial resistance of bacterial pathogens. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational principles, advanced bioinformatic workflows, and solutions for data challenges. By integrating current case studies—from bovine health to zoonotic diseases—and highlighting validation frameworks, the content establishes how genomic insights are driving the development of targeted therapies, novel antimicrobials, and precision medicine strategies to combat the global threat of antibiotic resistance.

Decoding Pathogen Evolution: Core Principles and Genomic Diversity

Defining Comparative Genomics and Its Impact on Human Health

Comparative genomics is the comparison of genetic information within and across organisms to understand the evolution, structure, and function of genes, proteins, and non-coding regions [1]. This field leverages a variety of tools to compare complete genome sequences of different species, pinpointing regions of similarity and difference to uncover fundamental biological insights [2]. By examining sequences from bacteria to humans, researchers can identify conserved DNA sequences preserved over millions of years, highlighting genes essential to life and genomic signals that control gene function across species [2] [3].

The field has evolved significantly since its origins in the 1980s with comparisons of viral genomes [3]. The first comparative genomic study at a larger scale was published in 1986, comparing the genomes of varicella-zoster virus and Epstein-Barr virus [3]. The completion of the first cellular organism genome (Haemophilus influenzae) in 1995 marked the beginning of modern comparative genomics, where every new genome sequence is now analyzed through this comparative lens [3] [4]. With advances in next-generation sequencing, comparative genomics has become increasingly sophisticated, enabling researchers to deal with many genomes simultaneously and apply these approaches to diverse areas of biomedical research [1] [3].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Understanding comparative genomics requires familiarity with several core concepts and terms that form the foundation of analytical approaches.

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Comparative Genomics

| Concept | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Orthologs | Genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene by speciation [3] | Often retain the same function in the course of evolution, crucial for functional annotation |

| Paralogs | Genes related by duplication within a genome [3] | May evolve new functions, contributing to functional diversification |

| Synteny | Preserved order of genes on chromosomes of related species [3] | Indicates descent from a common ancestor; identifies conserved genomic regions |

| Pan-genome | The full complement of genes in a species, including core and accessory genes [5] [6] | Core genes often encode essential functions; accessory genes confer niche-specific adaptations |

| Core genome | Genes shared by all strains of a species [5] [6] | Defines species identity and conserved biological functions |

| Accessory genome | Genes present in some but not all strains of a species [6] | Source of genetic variability, often associated with virulence, antibiotic resistance, and niche adaptation |

The principles of evolutionary selection form the theoretical foundation for interpreting comparative genomic data. Elements responsible for similarities between species are conserved through stabilizing selection, while differences result from divergent (positive) selection [3]. Elements unimportant to evolutionary success remain unconserved through neutral selection [3]. This evolutionary framework enables researchers to distinguish functionally important genomic elements from neutral sequences.

Impact on Human Health: Bacterial Pathogen Research

Comparative genomics provides powerful approaches for understanding bacterial pathogenesis, transmission, and treatment. The systematic comparison of bacterial pathogen genomes has yielded significant insights into mechanisms of virulence, antibiotic resistance, and host adaptation.

Understanding Pathogen Evolution and Virulence

Comparative genomic analyses of bacterial pathogens reveal how genetic variation contributes to differences in virulence and host specificity. By comparing genomes of pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains, researchers can identify genetic factors underlying pathogenicity.

Table 2: Key Findings from Comparative Genomic Analyses of Bacterial Pathogens

| Pathogen | Genomic Insight | Impact on Human Health |

|---|---|---|

| Listeria spp. | Absence of LIPI-1, LIPI-2, and LIPI-3 gene islands in non-pathogenic species despite conservation of other virulence genes [7] | Elucidates genetic basis of listeriosis; enables identification of hypervirulent strains |

| W. chitiniclastica | Pan-genome comprises 3,819 genes with 1,622 core genes (43%), indicating metabolic conservation [5] | Reveals evolutionary history of an emerging human pathogen; identifies potential drug targets |

| Multiple pathogens | Accessory genome is source of genetic variability allowing subpopulations to adapt to specific niches [6] | Explains how pathogens evolve to colonize new environments and hosts |

The analysis of Listeria species provides a compelling case study. Comparative genomics of pathogenic (L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii) and non-pathogenic (L. innocua, L. welshimeri) strains revealed that while all species share many virulence-associated genes, the absence of key pathogenicity islands (LIPI-1, LIPI-2, and LIPI-3) in non-pathogenic species likely explains their reduced virulence despite maintaining adhesion and invasion capabilities in vitro [7]. This demonstrates how comparative genomics can distinguish genuine virulence determinants from ancillary factors.

Antimicrobial Resistance and Therapeutic Development

Comparative genomics plays a crucial role in addressing the global threat of antimicrobial resistance by mapping the resistome - the full complement of antibiotic resistance genes in an organism. The World Health Organization has declared antimicrobial resistance one of the top ten global public health threats, necessitating novel approaches to combat this issue [1].

The analysis of W. chitiniclastica illustrates how comparative genomics reveals resistance mechanisms. While macrolide resistance genes macA and macB are located within the core genome of this species, additional antimicrobial resistance genes for tetracycline, aminoglycosides, sulfonamide, streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and beta-lactamase are distributed among the accessory genome [5]. Notably, the type strain DSM 18708ᵀ does not encode clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes, whereas drug resistance is increasing within the W. chitiniclastica clade, demonstrating the evolution of resistance in this emerging pathogen [5].

Comparative genomics also facilitates the discovery of novel antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which are gaining attention as potential therapeutic alternatives to conventional antibiotics. Frogs represent the most studied model organisms for AMPs, with 30% of peptides in the Antimicrobial Peptide Database first identified in frogs [1]. Each frog species possesses a unique repertoire of peptides (usually 10-20) that differs even from closely related species, providing a diverse library of molecules for therapeutic development [1].

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: Comparative Genomic Analysis of Bacterial Pathogens

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for comparing bacterial pathogen genomes to identify virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes, and evolutionary relationships.

Materials Required

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Genomic Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality DNA preparation for sequencing | CTAB method, commercial kits |

| Sequence Databases | Repository of genomic data for comparison | NCBI GenBank, RefSeq [5] |

| Assembly Software | Reconstruction of genome sequences from sequence reads | SPAdes, A5-miseq, Flye, Unicycler [7] |

| Annotation Pipelines | Identification and functional assignment of genomic features | NCBI PGAP, GeneMarkS, tRNAscan-SE [5] [7] |

| Comparative Analysis Tools | Detection of genomic variants, synteny, and evolutionary relationships | MUMMER, OrthoMCL, Roary [3] [6] |

| Specialized Databases | Curated collections of specific gene families | APD, CARD, VFDB [1] |

Methodology

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

- Extract genomic DNA using standardized methods (e.g., CTAB method with modifications) [7]

- Perform whole-genome sequencing using both Illumina (short-read) and Pacific Biosciences (long-read) platforms for complementary coverage

- Assemble sequences using hybrid approaches (e.g., SPAdes for Illumina data, Flye for PacBio data) followed by integration and polishing with tools like Pilon [7]

- Assess assembly quality using metrics (N50, contig number, completeness)

Genome Annotation and Functional Prediction

- Predict protein-coding genes using GeneMarkS or similar tools [7]

- Identify non-coding RNAs using tRNAscan-SE (tRNAs), Barrnap (rRNAs), and Rfam database (other non-coding RNAs) [7]

- Annotate gene functions using multiple databases: GO, KEGG, COG, NR, TCDB, EggNOG, CAZy, Swiss-Prot [7]

- Identify genomic islands using IslandViewer and prophages using PhiSpy [7]

Specialized Annotation for Pathogens

- Annotate virulence factors using specialized databases (VFDB, PATRIC)

- Identify antibiotic resistance genes using resources like CARD

- Characterize mobile genetic elements, CRISPR systems, and restriction-modification systems

Comparative Genomic Analysis

- Perform pan-genome analysis to identify core and accessory genomes using tools like Roary

- Construct phylogenetic trees based on core genome alignments

- Identify structural variants, rearrangements, and synteny breaks using MUMMER and similar tools

- Perform positive selection analysis on specific gene families

Troubleshooting Notes

- For fragmented assemblies, consider increasing sequencing depth or incorporating additional long-read data

- When annotation yields high numbers of "hypothetical proteins," consider using more sensitive homology detection methods (HHblits, PSI-BLAST)

- For phylogenetic inconsistencies, verify orthology relationships and consider horizontal gene transfer events

Protocol: Virulence Gene Identification in Listeria Species

This specific protocol details the identification of virulence determinants in Listeria species through comparative genomics, building on the research by [7].

Experimental Workflow

Detailed Procedures

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

- Obtain pathogenic (L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii) and non-pathogenic (L. innocua, L. welshimeri) strains

- Culture strains in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium at 37°C overnight with aeration

- Adjust bacterial cultures to OD₆₀₀ = 0.12 for standardized inocula

In vitro Virulence Assays

- Cell Culture: Maintain Caco-2 (human colon carcinoma) and RAW264.7 (macrophage) cells in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO₂

- Adhesion Assay:

- Seed cells in 12-well plates at 1×10⁵ cells/well and incubate until confluent

- Wash cells with PBS, add bacterial suspension at MOI of 100:1

- Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C with 5% CO₂

- Wash thoroughly with cold PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria

- Lyse cells with 0.2% Triton X-100, plate serial dilutions on BHI agar

- Calculate adhesion rate: (CFU adhered / Original inoculum CFU) × 100

- Invasion Assay:

- Infect cells as for adhesion assay and incubate for 1 hour

- Wash with PBS, add fresh medium containing 100 µg/mL gentamicin

- Incubate for additional hour to kill extracellular bacteria

- Wash with PBS, lyse cells with 0.2% Triton X-100

- Plate serial dilutions and count CFUs after incubation

- Calculate invasion rate: (CFU invaded / Original inoculum CFU) × 100

Genomic Analysis of Virulence Factors

- Annotate key virulence genes: prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, plcB, inlA, inlB

- Identify presence/absence of pathogenicity islands: LIPI-1, LIPI-2, LIPI-3

- Compare gene organization and synteny in virulence-associated regions

- Perform phylogenetic analysis of virulence genes

Expected Results and Interpretation Pathogenic strains typically show higher adhesion and invasion rates in cellular assays [7]. Genomic analyses should reveal the presence of complete LIPI-1 in pathogenic strains, while non-pathogenic strains lack these key pathogenicity islands despite potentially sharing other virulence-associated genes [7]. Discrepancies between genomic predictions and phenotypic assays may indicate novel virulence mechanisms or regulation differences.

Future Directions in Bacterial Pathogen Genomics

Comparative genomics is evolving rapidly with technological advancements. The NIH Comparative Genomics Resource (CGR) aims to address emerging challenges in data quantity, quality assurance, annotation, and interoperability [1] [8]. As sequencing technologies continue to improve, comparative genomics will expand to include more diverse bacterial pathogens, uncover rare genetic variants, and integrate multi-omics data for a comprehensive understanding of pathogen biology.

The integration of machine learning approaches with comparative genomic data holds particular promise for predicting emerging pathogens, anticipating antibiotic resistance evolution, and identifying novel therapeutic targets. These advances will enhance our ability to respond to infectious disease threats and develop targeted interventions for improved human health.

Bacterial pathogens exhibit a remarkable capacity to colonize diverse hosts and environments through rapid genomic evolution. The primary mechanisms driving this adaptation are gene acquisition via horizontal gene transfer (HGT), gene loss through reductive evolution, and point mutations that fine-tune existing functions [9]. Understanding these processes is crucial for tracking pathogen emergence, predicting virulence, and developing targeted antimicrobial strategies. Comparative genomic studies of bacterial pathogens have revealed that these mechanisms operate differently across ecological niches, with human-associated pathogens often displaying distinct genomic signatures compared to their environmental or animal-associated counterparts [9].

This application note provides a structured framework for investigating these adaptive mechanisms, featuring standardized protocols for experimental evolution, comparative genomics, and functional validation. The integrated approaches outlined below enable researchers to decipher the genetic basis of host specialization, antibiotic resistance emergence, and pathogenicity island acquisition in diverse bacterial systems.

Key Mechanisms of Bacterial Adaptation

Gene Acquisition Through Horizontal Gene Transfer

Horizontal gene transfer enables bacteria to rapidly acquire novel traits through three primary mechanisms: transformation, transduction, and conjugation. This process facilitates the spread of virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes, and metabolic pathway components across phylogenetic boundaries [10]. Pathogens frequently acquire genomic islands, plasmids, and phage elements that confer immediate selective advantages in new environments.

Research demonstrates that human-associated bacteria, particularly those from the phylum Pseudomonadota, extensively utilize gene acquisition strategies [9]. These organisms show significantly higher frequencies of carbohydrate-active enzyme genes and virulence factors related to immune modulation and adhesion, indicating targeted adaptation to human host environments. The genomic plasticity afforded by HGT enables rapid niche specialization and contributes to the emergence of novel pathogenic variants.

Gene Loss as an Adaptive Strategy

Contrary to traditional views that gene loss is necessarily deleterious, bacteria frequently undergo reductive evolution as an adaptive strategy [9]. This process involves the selective loss of non-essential genes that are redundant or costly in stable environments, allowing resource reallocation to more critical functions.

Mycoplasma genitalium exemplifies this strategy, having undergone extensive genome reduction including the loss of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism [9]. This streamlining enables the bacterium to maintain a parasitic relationship with its host while minimizing metabolic overhead. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that Actinomycetota and certain Bacillota lineages commonly employ genome reduction as an adaptive mechanism during host specialization [9].

Genomic and Metabolic Rearrangements

Beyond discrete gene gains and losses, bacteria undergo substantial genomic rearrangements and metabolic network rewiring during adaptation. These changes include promoter mutations that alter expression patterns, gene duplications that enable functional diversification, and integration of mobile genetic elements that bring new regulatory contexts to existing genes.

Experimental evolution studies with Escherichia coli have demonstrated that long-term adaptation to stable environments produces predictable patterns of genomic evolution, including parallel mutations in global regulators that coordinate metabolic priorities [11]. These regulatory changes often precede structural changes to enzyme-coding sequences, indicating hierarchical adaptation strategies.

Quantitative Analysis of Adaptive Signatures

Table 1: Niche-Specific Genomic Features in Bacterial Pathogens

| Ecological Niche | Enriched Genetic Elements | Primary Adaptive Mechanism | Example Phyla |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-Associated | Carbohydrate-active enzymes, immune modulation factors, adhesion virulence factors | Gene acquisition through HGT | Pseudomonadota |

| Clinical Settings | Antibiotic resistance genes (particularly fluoroquinolone resistance), efflux pumps | Plasmid-mediated HGT | Multiple phyla |

| Animal Hosts | Reservoirs of resistance genes, host-specific virulence factors | Both HGT and gene loss | Bacillota, Actinomycetota |

| Environmental | Transcriptional regulators, metabolic pathway genes, stress response elements | Gene loss/reductive evolution | Bacillota, Actinomycetota |

Table 2: Detection Methods for Horizontal Gene Transfer Events

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Primary Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Composition-Based | GC content deviation, codon usage bias, k-mer analysis | Initial screening of genomes for putative HGT | Limited detection of ancient transfers |

| Phylogenomic Approaches | Reconciliation of gene and species trees, anomalous phylogenetic patterns | Detecting HGT across deep evolutionary timescales | Computationally intensive |

| Mobile Genetic Element Focused | PlasmidFinder, MobileElementFinder, phage identification tools | Identifying vehicles of recent HGT | May miss chromosomal integrations |

| Experimental Validation | Laboratory evolution with sequencing, functional assays | Confirming adaptive benefit of HGT | May not reflect natural conditions |

Protocols for Studying Adaptation Mechanisms

Protocol: Experimental Evolution to Study Phage Adaptation to New Hosts

This protocol, adapted from Luzon-Hidalgo et al., provides a framework for investigating viral adaptation to novel hosts, with principles applicable to bacterial systems [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Experimental Evolution

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | DHB3 (araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 ΔlacX74 galE galK rpsL phoR Δ(phoA)PvuII ΔmalF3 thi) | Propagation strain for phage amplification |

| Engineered Host | FA41 cells (thioredoxin minus) cured of F' factor, lysogenized with T7 RNA polymerase | Novel host presenting evolutionary challenge |

| Growth Media | LB broth and LB agar | Standard microbial cultivation |

| Antibiotics | Appropriate selection markers (varies by plasmid system) | Maintenance of engineered genetic elements |

| Plasmids | pET30a(+) derivative with thioredoxin genes under T7 promoter | Expression of alternative proviral factors |

| Phage Stock | Bacteriophage T7 (NCBI reference: NC_001604.1) | Evolving viral entity |

Procedure

I. Phage Amplification and Titer Determination

Bacterial culture preparation: Inoculate 375 μL of an overnight E. coli culture into 15 mL fresh LB broth in a 50 mL tube (1:40 dilution). Incubate with shaking at 37°C until OD₆₀₀ reaches 0.5 (approximately 3-4 hours) [12].

Phage infection: Add 100 μL of phage suspension to 10 mL of the grown bacterial culture. Allow infection to proceed with shaking at 37°C for 4-5 hours until complete lysis is observed.

Phage stock purification: Aliquot bacterial lysate into 1.5 mL tubes and centrifuge at 15,871 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Transfer supernatants to new tubes and repeat centrifugation. Pool all supernatents to create a homogeneous amplified phage stock. Store in small aliquots at -20°C to avoid freeze-thaw cycles [12].

Titer determination via plaque assay: Prepare serial dilutions of phage stock in LB broth. Mix 100 μL of each dilution with 100 μL of fresh bacterial culture and 3 mL of molten soft agar (0.5% agar). Pour over pre-warmed LB agar plates and allow to solidify. Incubate overnight at 37°C and count plaque-forming units (pfu) the next day [12].

II. Experimental Evolution Cycles

Initial propagation: Infect the engineered host (containing alternative thioredoxin) with the amplified wild-type phage stock at appropriate multiplicity of infection.

Recovery of evolved variants: Harvest phage progeny after complete lysis or sufficient incubation period (typically 4-24 hours). Purify through centrifugation as described above.

Serial passage: Use progeny from each successful infection to initiate subsequent infection rounds in the novel host. Monitor infection efficiency through plaque assays at regular intervals [12].

Phenotypic characterization: Compare lysis profiles of evolved phages against ancestral strain through one-step growth curves and efficiency of plating assays.

III Genomic Analysis of Adaptations

DNA extraction: Extract genomic DNA from evolved phage suspensions using commercial kits with modifications for viral DNA.

Next-generation sequencing: Prepare libraries and sequence using Illumina platforms (2 × 150 bp paired-end recommended).

Variant identification: Map sequences to reference genome, identify mutations, and validate through Sanger sequencing.

Functional validation: Introduce identified mutations into ancestral background through site-directed mutagenesis to confirm adaptive role.

Protocol: Comparative Genomic Analysis of Bacterial Adaptation

This protocol outlines a bioinformatics workflow for identifying adaptive signatures across bacterial genomes from different ecological niches [9].

Genome Dataset Collection and Curation

Data acquisition: Obtain bacterial genome sequences from public repositories (e.g., NCBI, gcPathogen). Curate metadata to include isolation source, host information, and collection date.

Quality control: Implement stringent filtering criteria including: assembly level (prefer chromosome/scaffold over contig), N50 ≥ 50,000 bp, CheckM completeness ≥ 95%, contamination < 5% [9].

Niche categorization: Annotate genomes with ecological niche labels (human, animal, environment) based on isolation source and host information.

Redundancy reduction: Calculate genomic distances using Mash and perform clustering (e.g., Markov clustering) to remove genomes with distances ≤ 0.01, ensuring non-redundant dataset [9].

Phylogenetic and Population Structure Analysis

Marker gene extraction: Identify 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome using AMPHORA2 [9].

Sequence alignment: Perform multiple sequence alignment for each marker gene using Muscle v5.1.

Phylogenetic reconstruction: Concatenate alignments and construct maximum likelihood tree using FastTree v2.1.11. Visualize through iTOL.

Population clustering: Convert phylogenetic tree to distance matrix and perform k-medoids clustering using silhouette coefficient to determine optimal cluster number [9].

Functional Annotation and Comparative Analysis

Gene prediction: Predict open reading frames using Prokka v1.14.6.

Functional categorization: Map ORFs to Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST (e-value threshold 0.01, minimum coverage 70%).

Specialized annotation:

- Carbohydrate-active enzymes: Annotate using dbCAN2 and HMMER (hmm_eval 1e-5) against CAZy database [9].

- Virulence factors: Query VFDB using Abricate v1.0.1.

- Antibiotic resistance genes: Annotate using CARD database with Abricate or AMRFinderPlus.

Pan-genome analysis: Calculate core and accessory genome using Roary v3.11.2 (≥95% amino acid identity, core gene defined as present in ≥99% isolates).

Association testing: Identify genes significantly associated with specific niches using Scoary with phylogenetic correction.

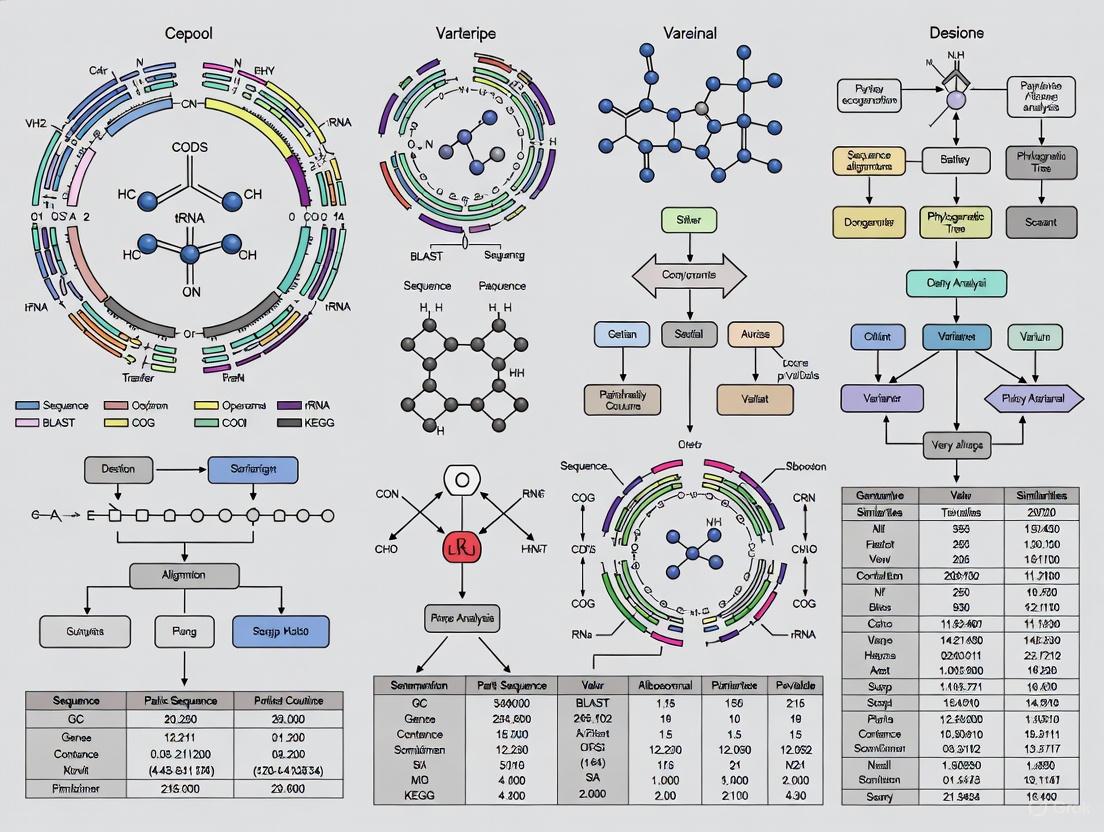

Workflow Visualization

Experimental and Computational Workflow for Studying Bacterial Adaptation

The integrated experimental and computational approaches detailed in this application note provide a comprehensive framework for investigating bacterial adaptation mechanisms. By combining controlled evolution experiments with large-scale comparative genomics, researchers can decipher the genetic basis of host specialization, antibiotic resistance emergence, and niche adaptation in bacterial pathogens.

These protocols have direct applications in public health surveillance, antimicrobial stewardship, and drug development. Identifying niche-specific genetic signatures enables proactive monitoring of zoonotic threats, while understanding adaptation mechanisms informs strategies to counter resistance development. The continued refinement of these methodologies will enhance our predictive capabilities in bacterial evolution and pathogen emergence.

Pan-genome analysis represents a transformative approach in microbial genomics that moves beyond the limitations of single reference genomes to encompass the complete repertoire of genes within a bacterial species. Originally introduced by Tettelin et al. in 2005 during genomic studies of Streptococcus agalactiae, the pan-genome concept has revolutionized how researchers conceptualize bacterial diversity and evolution [13] [14]. For bacterial pathogens, this approach is particularly valuable as it enables systematic investigation of genomic elements underlying virulence, host adaptation, antibiotic resistance, and other clinically relevant traits. The pan-genome is partitioned into distinct components: the core genome (genes shared by all isolates), the dispensable or accessory genome (genes present in some but not all isolates), and strain-specific genes (unique to individual isolates) [14] [15]. This classification provides a powerful framework for understanding the genetic basis of pathogenicity and ecological adaptation.

The importance of pan-genome analysis in bacterial pathogen research stems from its ability to capture the extensive genomic plasticity that characterizes many pathogenic species. Horizontal gene transfer, recombination, and genomic rearrangements contribute significantly to the accessory genome, often encoding functions related to host-pathogen interactions, niche adaptation, and antimicrobial resistance [16] [9]. Recent studies have demonstrated that pathogenic bacteria frequently utilize gene acquisition and loss as evolutionary strategies to adapt to specific host environments and selective pressures, such as antibiotic exposure [9]. For instance, comparative genomic analyses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from different ecological niches have revealed distinctive genomic signatures associated with human pathogenesis versus environmental survival [9]. By providing a comprehensive view of species-wide genetic diversity, pan-genome analysis enables researchers to identify virulence determinants, track transmission pathways, understand outbreak dynamics, and develop novel therapeutic targets against problematic pathogens.

Computational Methods and Workflows

Pan-Genome Construction Strategies

The construction of a bacterial pan-genome typically employs one of three primary computational approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The reference-based mapping approach aligns sequencing reads from multiple isolates to a high-quality reference genome, identifying presence-absence variations (PAVs) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). While computationally efficient, this method is inherently biased toward the reference and may miss novel sequences not present in the reference genome [17] [13]. The de novo assembly approach involves independently assembling complete genomes for multiple isolates followed by comparative analysis to identify core and accessory elements. This method provides more comprehensive variant detection, including structural variations (SVs) in repetitive regions, but demands substantial computational resources and expertise [17] [15]. The graph-based pan-genome approach represents genomic sequences as nodes in a graph structure, with edges connecting overlapping or homologous regions. This method excels at capturing complex structural variations and naturally represents sequence diversity, though graph construction and traversal can be computationally intensive, especially for large datasets [17] [13].

For bacterial pathogens, the choice of construction method depends on research objectives, dataset scale, and computational resources. Reference-based approaches may suffice for closely related isolates of clinical interest, while de novo or graph-based methods are preferable for capturing the full genomic diversity of heterogeneous pathogen populations. A systematic evaluation of available tools indicates that different pipelines vary significantly in their performance characteristics. PGAP2, for instance, employs a fine-grained feature analysis within constrained regions to rapidly and accurately identify orthologous and paralogous genes, demonstrating superior precision and robustness compared to other tools when processing large-scale pan-genome data [16].

Ortholog Identification and Gene Classification

Accurate identification of orthologous genes is fundamental to pan-genome analysis, as errors at this stage propagate through downstream analyses. Most pipelines employ sequence similarity searches (e.g., BLAST, DIAMOND) followed by clustering algorithms (e.g., OrthoFinder, Panaroo) to group homologous genes into orthologous clusters [16] [14]. PGAP2 implements a sophisticated approach that organizes data into gene identity and gene synteny networks, then applies a dual-level regional restriction strategy to refine orthologous gene inference while minimizing computational complexity [16]. This method evaluates gene clusters using three criteria: gene diversity, gene connectivity, and the bidirectional best hit (BBH) criterion for duplicate genes within the same strain [16].

Following ortholog identification, genes are classified into categories based on their distribution patterns across the analyzed genomes. The standard classification system includes core genes (present in all isolates, typically encoding essential cellular functions), soft-core genes (present in ≥95% of isolates), shell genes (present in 15-95% of isolates), and cloud genes (present in <15% of isolates, often strain-specific) [14] [15]. Some classification systems also include private genes that are unique to a single isolate [14]. These categories provide insights into evolutionary conservation and functional specialization within bacterial populations.

Table 1: Standard Gene Categories in Bacterial Pan-Genome Analysis

| Category | Presence Threshold | Typical Functional Enrichment | Evolutionary Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Genes | 100% of isolates | Primary metabolism, DNA replication, transcription, translation | Evolutionarily conserved, vertical inheritance |

| Soft-Core Genes | ≥95% of isolates | Metabolic flexibility, regulatory functions | Highly conserved with minor population-specific variation |

| Shell Genes | 15-95% of isolates | Environmental sensing, niche adaptation, antimicrobial resistance | Subject to frequent gain/loss, often linked to mobile elements |

| Cloud Genes | <15% of isolates | Phage-related functions, hypothetical proteins | Recently acquired, strain-specific, potentially transient |

| Private Genes | Single isolate | Horizontal acquisitions, strain-specific adaptations | Recently acquired, may represent annotation artifacts |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized computational workflow for bacterial pan-genome analysis, integrating the key steps from data preparation through downstream applications:

Application Notes for Bacterial Pathogen Research

Protocol 1: Comparative Genomic Analysis of Pathogen Populations

Objective: To identify genomic features associated with host adaptation and virulence in bacterial pathogens across different ecological niches.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality genome assemblies for multiple bacterial isolates (minimum 10-15 recommended)

- High-performance computing infrastructure with sufficient memory and storage

- Bioinformatic software tools (see Table 2)

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation and Quality Control: Collect genome sequences with comprehensive metadata including isolation source, host information, geographical location, and collection date. Implement stringent quality control measures including CheckM evaluation (completeness ≥95%, contamination <5%) and removal of highly similar strains (genomic distance ≤0.01) to reduce redundancy [9].

- Pan-Genome Construction: Utilize PGAP2 or similar pipelines that accept multiple input formats (GFF3, GBFF, FASTA). PGAP2 automatically selects a representative genome based on gene similarity and identifies outliers using average nucleotide identity (ANI) thresholds and unique gene counts [16].

- Functional Annotation: Annotate protein-coding genes using Prokka or similar tools. Map predicted open reading frames to functional databases including COG (cellular functions), dbCAN2 (carbohydrate-active enzymes), VFDB (virulence factors), and CARD (antibiotic resistance genes) using sequence similarity searches with appropriate e-value thresholds (e.g., 0.01) and coverage filters [9].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate pan-genome characteristics including core/accessory proportions and gene presence-absence frequencies. Perform enrichment analysis using Fisher's exact tests or hypergeometric tests to identify functions overrepresented in specific phylogenetic clades or ecological niches. Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forests) to identify genomic features predictive of host specificity or clinical outcomes [9].

Expected Outcomes: This protocol enables identification of niche-specific genomic signatures, including enrichment of virulence factors in clinical isolates, antibiotic resistance genes in hospital-associated strains, and metabolic adaptations in environmental populations. A recent study applying this approach to 4,366 bacterial pathogens revealed that human-associated Pseudomonadota exhibited higher frequencies of carbohydrate-active enzyme genes and immune evasion factors, while environmental isolates showed greater enrichment of metabolic and transcriptional regulatory genes [9].

Protocol 2: Identification of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Determinants

Objective: To characterize the distribution and genetic context of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes and virulence factors across pathogen populations.

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial genomes with associated antimicrobial susceptibility profiles

- Reference databases: CARD, VFDB, NCBI AMRFinderPlus

- Visualization tools: Phandango, BRIG, Proksee

Methodology:

- Gene Detection: Identify AMR genes and virulence factors using a combination of sequence similarity (BLAST, DIAMOND) and hidden Markov model (HMM) approaches against specialized databases. For comprehensive AMR annotation, use tools like RGI (Resistance Gene Identifier) with the CARD database.

- Contextual Analysis: Examine genomic neighborhoods of identified AMR/virulence genes to determine their association with mobile genetic elements (plasmids, transposons, integrons) using tools like MobileElementFinder.

- Association Testing: Correlate gene presence-absence patterns with metadata on antibiotic resistance phenotypes, host specificity, or clinical manifestations using statistical tests (e.g., Fisher's exact test) and phylogenetic methods to account for population structure.

- Visualization: Generate circular genome comparisons to visualize the distribution and genomic context of AMR/virulence genes across multiple isolates.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol facilitates tracking of mobile resistance elements across pathogen populations, identification of emerging resistance threats, and discovery of novel virulence mechanisms. Application to clinical Streptococcus suis isolates has revealed extensive variation in virulence gene content associated with differential disease outcomes [16].

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Bacterial Pan-Genome Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Assembly | Hifiasm, Unicycler, SPAdes | De novo genome assembly from sequencing reads | Critical for generating high-quality inputs; long-read technologies improve contiguity |

| Annotation | Prokka, Bakta, RAST | Structural and functional gene annotation | Standardized annotation essential for comparative analyses |

| Ortholog Identification | OrthoFinder, Roary, Panaroo, PGAP2 | Homology detection and orthologous group clustering | PGAP2 shows superior accuracy for large datasets [16] |

| Variant Analysis | Snippy, Breseq, SVcaller | SNP and structural variant detection | Important for understanding microevolution within species |

| Functional Analysis | eggNOG-mapper, COG, dbCAN2 | Functional annotation and enrichment | Links genomic variation to biological processes |

| Specialized Databases | VFDB, CARD, dbCAN | Pathogen-specific functional annotation | Essential for virulence and resistance profiling |

| Visualization | Phandango, ITOL, PanX | Interactive visualization of pan-genomes | Facilitates exploration and interpretation of results |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful pan-genome analysis requires both computational tools and carefully curated biological materials. The following table outlines essential research reagents and resources for comprehensive pan-genome studies of bacterial pathogens:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Bacterial Pan-Genome Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Function in Pan-Genome Analysis | Quality Control Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Isolates | Diverse ecological/geographical origins; comprehensive metadata | Represents species genetic diversity; enables correlation of genomic features with phenotype | Purity verification; contamination screening; accurate source documentation |

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-molecular-weight DNA suitable for long-read sequencing | Input material for high-quality genome assemblies | Quantification (fluorometric); integrity assessment (pulse-field gel electrophoresis) |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina (coverage), PacBio HiFi/Nanopore (contiguity) | Generates raw data for assembly and variant detection | Appropriate coverage depth (typically 50-100x for Illumina, 20-30x for long reads) |

| Reference Genomes | High-quality, complete assemblies with annotation | Basis for reference-based approaches; functional inference | Assessment of completeness (BUSCO), continuity (N50), annotation quality |

| Functional Databases | COG, KEGG, VFDB, CARD, dbCAN | Functional annotation of gene clusters | Regular updates; careful curation to minimize false annotations |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-performance computing cluster with ample storage | Data processing, analysis, and storage | Sufficient RAM for large assemblies; backup systems for data preservation |

Data Interpretation and Analytical Considerations

Statistical Framework and Quantitative Parameters

Pan-genome analysis generates complex datasets that require appropriate statistical frameworks for robust interpretation. A key initial consideration is determining whether the pan-genome is "open" or "closed" using Heaps' law, which models the relationship between newly sequenced genomes and novel gene discovery [15]. The mathematical formulation follows the power-law function: $n = kN^α$, where $n$ represents the total number of unique genes identified after sequencing $N$ genomes, $k$ is a constant reflecting vocabulary growth rate, and $α$ indicates pan-genome openness [15]. An $α$ value >1 typically suggests an open pan-genome where new genes continue to be discovered with additional sequencing, while $α$ <1 indicates a closed pan-genome where sequencing additional isolates yields diminishing returns in novel gene discovery.

PGAP2 introduces four quantitative parameters derived from inter- and intra-cluster distances that enable detailed characterization of homology clusters [16]. These metrics facilitate more nuanced interpretations of pan-genome dynamics beyond simple presence-absence counts. For phylogenetic analysis, maximum likelihood trees constructed from concatenated alignments of universal single-copy genes provide robust evolutionary frameworks for interpreting the distribution of accessory genes [9]. Population genetic statistics such as nucleotide diversity (π) and fixation indices (FST) can further illuminate population structure and selection pressures acting on different genomic compartments [9].

Technical Challenges and Limitations

Despite methodological advances, bacterial pan-genome analysis still faces several technical challenges. The quality of input genomes significantly impacts results, with fragmented assemblies or incomplete annotations leading to inaccurate gene presence-absence calls [15]. Highly repetitive regions, mobile genetic elements, and recent gene duplications present particular difficulties for orthology detection algorithms [16]. For accessory genes with patchy distributions, distinguishing genuine biological absence from assembly or annotation artifacts remains challenging; integration with transcriptomic data can help validate functionally expressed genes [15].

Computational resource requirements can be substantial, particularly for graph-based approaches analyzing hundreds or thousands of genomes [17]. The choice of clustering thresholds significantly impacts gene categorization, yet optimal settings vary across bacterial taxa due to differences in evolutionary rates and genome dynamics [14]. Pan-genome analyses are also sensitive to sampling bias, where overrepresentation of certain lineages (e.g., clinical isolates versus environmental strains) can skew estimates of core and accessory genome sizes [9]. Careful study design incorporating phylogenetically diverse isolates with comprehensive metadata collection helps mitigate these limitations and enables more biologically meaningful interpretations.

Pan-genome analysis has emerged as an indispensable framework for comparative genomics of bacterial pathogens, providing unprecedented insights into their evolutionary dynamics, adaptive mechanisms, and pathogenic potential. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this article equip researchers with standardized approaches for constructing and analyzing pan-genomes to address diverse microbiological questions. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, pan-genome approaches will play an increasingly central role in tracking the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance, identifying novel therapeutic targets, informing vaccine design, and ultimately improving our ability to combat infectious diseases. The integration of pan-genomics with functional studies, population genomics, and epidemiological data represents a promising frontier for understanding the genetic basis of pathogenicity and developing novel interventions against problematic pathogens.

Bovine mastitis, an inflammatory condition of the mammary gland, presents a substantial economic burden to the global dairy industry, with annual losses estimated between USD 19.7 and 32 billion [18]. Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli represent two of the most significant bacterial pathogens responsible for clinical and subclinical mastitis cases worldwide. This application note explores the genomic diversity of these pathogens through the lens of comparative genomic analysis, providing researchers with standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to investigate mastitis pathogenesis, transmission dynamics, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. The insights derived from such analyses are crucial for developing targeted interventions and improving bovine health management practices in dairy production systems.

Genomic Profiles of Major Mastitis Pathogens

1Staphylococcus aureusGenomic Epidemiology

Staphylococcus aureus demonstrates significant genomic plasticity with distinct clonal complexes (CCs) dominating bovine mastitis cases across different geographical regions. Comparative genomic studies reveal specific adaptations in bovine-associated lineages.

Table 1: Global Distribution of S. aureus Clonal Complexes in Bovine Mastitis

| Clonal Complex | Geographical Distribution | Associated Mastitis Type | Key Virulence Factors | Antimicrobial Resistance Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC151 [19] | Widespread (29.3% European isolates) [19] | Subclinical and Clinical [19] | lukM-lukF', Various superantigens [19] | Limited AMR genes [19] |

| CC97 [20] [19] | Prevalent in India and Europe (19.6%) [20] [19] | Subclinical and Clinical [19] | Moderate lukM-lukF' carriage (30%) [19] | blaZ (30%) [19] |

| CC479 [19] | Regional (11.6% European isolates) [19] | Associated with Clinical Mastitis (OR 3.62) [19] | lukM-lukF', SaPI vWFbp, Superantigens [19] | Limited AMR genes [19] |

| CC398 [19] | Poland and Spain [19] | Subclinical and Clinical [19] | Lacks key virulence factors [19] | High blaZ, tetM, mecA carriage [19] |

| CC8 [20] | India and Europe [20] [19] | Subclinical and Clinical [19] | Variable [19] | Variable [19] |

2Escherichia coliGenomic Epidemiology

Mammary pathogenic E. coli (MPEC) strains display a distinct phylogenetic distribution compared to human pathogenic variants, with specific genetic loci associated with adaptation to the bovine mammary environment.

Table 2: Characteristics of Mastitis-Associated Escherichia coli (MPEC)

| Characteristic | Profile | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogroup Distribution [21] [22] | Primarily Phylogroup A and B1 [21] [22] | Contrasts with human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) which often belong to groups B2 and D [21] |

| Virulence Gene Carriage [21] | Few recognized virulence genes from other pathogenic pathovars [21] | Suggests niche-specific adaptation factors rather than conventional virulence genes |

| MPEC-Specific Loci [22] | ycdU-ymdE genes, phenylacetic acid degradation pathway, ferric citrate uptake system [22] | Identified through pan-genomic analysis as core to MPEC but dispensable in other E. coli [22] |

| Phylogenetic Diversity [22] | Significantly reduced compared to general phylogroup A population (p = 0.00015) [22] | Indicates selective enrichment of specific lineages capable of causing mastitis [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Genomic Analysis

Whole Genome Sequencing and Assembly Protocol

Objective: Obtain high-quality genome sequences for comparative genomic analysis of mastitis pathogens.

Materials:

- Bacterial isolates from clinical or subclinical mastitis milk samples

- DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent [23] [20]

- Illumina sequencing platform (HiSeq, NextSeq) [23] [20]

- Computational resources with at least 16GB RAM

Procedure:

DNA Extraction

- Grow bacterial isolates overnight in appropriate medium (e.g., BHI broth for S. aureus)

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial kits following manufacturer's protocol

- Assess DNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) and fluorometry (e.g., Qubit)

- Ensure DNA integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Fragment DNA to ~500bp using acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation

- Prepare sequencing libraries using Illumina-compatible library preparation kits

- Perform quality control on libraries using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation

- Sequence on Illumina platform to achieve minimum 50x coverage (2×150bp paired-end recommended)

Genome Assembly and Annotation

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low coverage: Check DNA quality and optimize fragmentation

- Poor assembly: Increase sequencing depth or employ hybrid assembly approaches

- Contamination: Screen for non-target DNA using 16S rRNA analysis

Comparative Genomic Analysis Protocol

Objective: Identify variations in gene content, phylogenetic relationships, and virulence determinants among mastitis isolates.

Materials:

- Assembled and annotated genome sequences

- Reference genomes (e.g., S. aureus strain K5 for SNP calling) [20]

- Computational resources with Linux environment and appropriate software

Procedure:

Pan-Genome Analysis

Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

Virulence and Resistance Gene Profiling

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Analysis

Expected Outcomes:

- Pan-genome statistics (core, accessory, and unique gene counts)

- Phylogenetic relationships and population structure

- Virulence and resistance gene profiles associated with specific lineages

- Identification of genetic markers for mastitis-associated clones

Visualization of Genomic Analysis Workflow

Genetic Basis of Mastitis Pathogenesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mastitis Pathogen Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit [23] [20] | High-quality genomic DNA isolation | DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent |

| Library Prep Kit [23] | Sequencing library preparation | Illumina DNA Prep kits or equivalent |

| Sequencing Platform [23] [20] | Whole genome sequencing | Illumina HiSeq/NextSeq for short-read; PacBio/Oxford Nanopore for long-read |

| Assembly Software [23] [20] | Genome assembly from sequencing reads | SPAdes v3.11.1+ for Illumina data |

| Annotation Tools [23] [20] | Gene prediction and functional annotation | PROKKA, RAST |

| Typing Databases [20] | Strain classification and epidemiology | PubMedST for MLST analysis |

| Specialized Databases [23] [20] | Virulence and resistance gene identification | CARD (AMR), VFDB (Virulence Factors) |

| Phylogenetic Tools [23] [20] | Evolutionary relationship inference | kSNP v.3 (SNP-based), Roary (gene presence/absence) |

Discussion and Research Implications

The comparative genomic analysis of bovine mastitis pathogens reveals distinct evolutionary strategies employed by S. aureus and E. coli to colonize the bovine mammary gland. S. aureus exhibits a clonal population structure with specific CCs enriched in virulence factors that promote immune evasion and persistence, such as the ruminant-specific leukocidin LukMF' [19] [18]. In contrast, MPEC strains are characterized not by conventional virulence factors but by niche-specific adaptations including specialized iron acquisition systems and metabolic pathways [21] [22].

From a diagnostic perspective, the identification of CC-specific markers in S. aureus and MPEC-specific loci in E. coli enables development of rapid molecular tests to identify high-risk strains. For instance, the detection of CC479 S. aureus, which is strongly associated with clinical mastitis (OR 3.62) [19], could inform targeted intervention strategies. Similarly, the ferric citrate uptake system in MPEC represents a potential therapeutic target for novel interventions.

The regional variation in dominant clones, with CC97 prevalent in Indian isolates [20] and CC151 widespread in Europe [19], highlights the importance of geographic factors in strain distribution and the necessity for region-specific control strategies. Furthermore, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in certain lineages, particularly the high prevalence of tetracycline resistance (tetM) and methicillin resistance (mecA) in CC398 [19], underscores the need for continuous genomic surveillance to monitor the spread of resistant clones.

These genomic insights facilitate a more precise approach to mastitis management through improved diagnostics, targeted therapies, and evidence-based control measures, ultimately reducing the economic impact of this disease while promoting antimicrobial stewardship in dairy production systems.

Regional Variations and Host-Specific Adaptations in Pathogen Populations

Understanding the genetic mechanisms behind regional variations and host-specific adaptations is a fundamental objective in bacterial pathogen research. Pathogens exhibit a remarkable capacity to evolve distinct genomic features in response to selective pressures imposed by different ecological niches and host organisms [9]. Comparative genomic analyses have revealed that bacterial pathogens employ diverse adaptive strategies, including gene acquisition through horizontal gene transfer and reductive evolution through gene loss, to specialize for survival in specific environments [9] [25]. The significance of this research is framed within the One Health approach, which recognizes the complex interdependencies connecting human, animal, and environmental health [9].

Large-scale genomic studies demonstrate that human-associated bacteria, particularly from the phylum Pseudomonadota, frequently acquire genes encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes and virulence factors related to immune modulation and adhesion, indicating a pattern of co-evolution with the human host [9] [25]. In contrast, environmental isolates often show enrichment in genes for metabolic versatility and transcriptional regulation, while clinical settings select for elevated numbers of antibiotic resistance genes [9]. This Application Note provides a structured genomic framework, detailed protocols, and analytical tools to investigate these critical adaptive mechanisms, enabling researchers to decipher the molecular basis of pathogen evolution and transmission dynamics.

Key Genomic Findings on Niche Adaptation

Comparative analysis of 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes has quantified significant genomic differences across ecological niches. The table below summarizes the key adaptive signatures identified in major bacterial phyla from different sources [9].

Table 1: Niche-Specific Genomic Adaptations Across Bacterial Phyla

| Ecological Niche | Primary Adaptive Strategy | Enriched Gene Categories | Representative Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Host | Gene acquisition | Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), virulence factors (immune modulation, adhesion) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli [9] [25] |

| Animal Host | Gene acquisition & reservoir function | Virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes | Staphylococcus aureus (livestock-associated) [9] |

| Clinical Environment | Gene acquisition (antibiotic resistance) | Fluoroquinolone resistance genes, other AMR determinants | Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa [9] [26] |

| Natural Environment | Genome reduction & metabolic diversification | Metabolic pathways, transcriptional regulation | Vibrio parahaemolyticus environmental ecotypes [9] |

Further analysis at the species level reveals specific genetic changes driving host preference. Studies on Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic clones have identified a transcriptional signature of 624 genes positively associated and 514 genes inversely associated with an affinity for causing cystic fibrosis (CF) infections [26]. A key finding is the role of the stringent response modulator DksA1, whose expression is linked to enhanced intracellular survival within macrophages, a trait critical for persistence in CF patients [26]. This highlights how specific regulatory genes can underpin host-specific adaptation and virulence.

Application Notes: Experimental Framework for Analyzing Host Adaptation

Core Computational and Genomic Workflow

A robust experimental framework for analyzing host adaptation involves a sequential process from genome collection to functional validation. The following workflow outlines the key stages for identifying and characterizing niche-specific signature genes.

Figure 1: A unified workflow for the comparative genomic analysis of host adaptation.

Protocol: Comparative Genomic Analysis for Identifying Host-Specific Adaptations

Objective: To identify niche-associated signature genes and genomic adaptations in bacterial pathogens from different hosts and environments.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality bacterial genome sequences

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or server

- Bioinformatic software suites (detailed in Section 5.0)

Procedure:

Genome Dataset Curation and Quality Control

- Source genome metadata from public databases (e.g., gcPathogen) [9].

- Apply stringent quality filters: retain genomes with assembly N50 ≥ 50,000 bp, CheckM completeness ≥ 95%, and contamination < 5% [9] [25].

- Annotate each genome with an ecological niche label ("human," "animal," "environment") based on isolation source metadata [9].

- Remove redundant genomes by calculating genomic distances with Mash and performing clustering (e.g., remove genomes with distance ≤ 0.01) to obtain a non-redundant dataset [9].

Phylogenetic Reconstruction and Population Clustering

- Identify 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome using AMPHORA2 [9].

- Perform multiple sequence alignment for each marker gene using Muscle v5.1 [9].

- Concatenate alignments and construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using FastTree v2.1.11 [9].

- Convert the phylogenetic tree into an evolutionary distance matrix and perform k-medoids clustering (e.g., using the

pamfunction in R) to define population clusters for downstream comparative analysis [9].

Functional Annotation and Enrichment Analysis

- Predict Open Reading Frames (ORFs) using Prokka v1.14.6 [9] [25].

- Annotate gene functions by mapping ORFs to the following databases:

- COG Database: Use RPS-BLAST (e-value threshold 0.01, minimum coverage 70%) for functional categorization [9].

- CAZy Database: Use dbCAN2 (HMMER tool, hmm_eval 1e-5) to annotate carbohydrate-active enzyme genes [9].

- Virulence Factors: Use ABRicate v1.0.1 with the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) to identify virulence genes [9] [25].

- Antibiotic Resistance: Use ABRicate with the CARD database to identify antimicrobial resistance genes [9].

- Perform enrichment analysis (e.g., Fisher's exact test) to identify COG categories, virulence factors, and resistance genes significantly overrepresented in specific ecological niches [9].

Identification of Host-Specific Signature Genes

Application Notes: Investigating Intrinsic Host Preference and Transmission

Core Workflow for Analyzing Epidemic Clone Behavior

Understanding why certain epidemic clones exhibit a strong preference for a specific host requires moving beyond genomics to transcriptomics and phenotypic assays. The process below details the key steps for this functional investigation.

Figure 2: A functional analysis workflow for intrinsic host preference mechanisms.

Protocol: Functional Characterization of Host Preference Mechanisms

Objective: To determine the molecular basis for the intrinsic preference of epidemic bacterial clones for specific host types (e.g., Cystic Fibrosis vs. non-CF patients).

Materials and Reagents:

- Representative bacterial isolates from defined epidemic clones (e.g., high-CF-affinity ST27 vs. low-affinity ST235)

- Wild-type and CF (e.g., F508del homozygous) isogenic macrophage cell lines

- Cell culture materials and invasion media

- Zebrafish model for in vivo infection studies

- Materials for genetic manipulation (e.g., knockout plasmids)

Procedure:

Transcriptomic Profiling of Epidemic Clones

- Culture representative isolates from epidemic clones with known host preferences under standardized conditions.

- Extract total RNA and perform RNA-Seq analysis.

- Identify differentially expressed genes between clones with high and low affinity for a specific host (e.g., CF) using a negative binomial generalized linear model (Wald test, FDR = 0.05) [26].

Phenotypic Screening Using Macrophage Survival Assay

- Differentiate human THP-1 cells into macrophages.

- Infect macrophages with bacterial isolates at a defined Multiplicity of Infection (MOI).

- After a set period of incubation, lyse the macrophages and plate the lysates on agar to enumerate intracellular bacteria.

- Compare the intracellular survival and replication rates of isolates from high- and low-affinity clones [26].

Genetic Validation of Key Regulatory Genes

- Select a candidate gene identified from transcriptomic analysis (e.g., dksA1).

- Construct a knockout mutant (e.g., ΔdksA1,2 double knockout) in a wild-type background (e.g., PAO1) [26].

- Complement the mutant by reintroducing the wild-type gene on a plasmid.

- Repeat the macrophage survival assay with the wild-type, knockout, and complemented strains to confirm the gene's role in intracellular survival, particularly in CF macrophage models [26].

In Vivo Validation in Animal Models

- Use a zebrafish model with morpholino knockdown of the cftr gene to simulate a CF-like environment.

- Inject wild-type and mutant bacterial strains intravenously and monitor host survival and bacterial burden over time to validate findings from in vitro models [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Comparative Genomics

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example/Version |

|---|---|---|

| Prokka | Rapid annotation of bacterial genomes [9]. | v1.14.6 |

| dbCAN2 | Annotation of carbohydrate-active enzymes in genomes [9]. | HMMER tool (hmm_eval 1e-5) |

| VFDB | Database for identifying virulence factors [9]. | Used with ABRicate v1.0.1 |

| CARD | Database for predicting antibiotic resistance genes [9]. | Used with ABRicate v1.0.1 |

| Scoary | Pan-genome genome-wide association study (GWAS) tool [9]. | Used to identify niche-associated genes |

| Panaroo | Graph-based pangenome clustering and analysis [26]. | Used to define core/accessory genome |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Machine learning model for pathogenicity classification [9] [27]. | L1-norm regularization for feature selection |

| THP-1 Cell Line | Human monocyte cell line, differentiated into macrophages for infection assays [26]. | Wild-type and CF (F508del) isogenic lines |

| Zebrafish Model | In vivo model for studying host-pathogen interactions and virulence [26]. | cftr morpholino knockdown |

From Sequence to Insight: Advanced Workflows and Biomedical Applications

High-quality genome curation represents a critical foundation for comparative genomic analyses of bacterial pathogens, enabling researchers to decipher the genetic underpinnings of virulence, antimicrobial resistance, and host adaptation. The process transforms raw sequence data into biologically meaningful information through systematic annotation, validation, and functional classification. Within bacterial pathogen research, meticulous curation is particularly vital as it directly impacts the identification of therapeutic targets, understanding of transmission dynamics, and development of diagnostic tools. Current genomic resources have evolved significantly to support these investigations, with international databases maintaining standardized information on millions of microbial sequences [28]. The establishment of consistent curation standards ensures that data remains interoperable across platforms, reproducible across studies, and biologically accurate for downstream analyses, ultimately strengthening the reliability of scientific findings in infectious disease research.

The burgeoning volume of genomic data from advanced sequencing technologies presents both unprecedented opportunities and substantial challenges for pathogen genomics. As noted in a comprehensive analysis of 4,366 bacterial pathogen genomes, rigorous quality control and standardized annotation pipelines are essential for meaningful comparative studies [9]. The integration of curated metadata regarding isolation source, host information, and collection date further enhances the utility of these genomic resources for tracking disease outbreaks and understanding pathogen evolution. This application note details the contemporary standards, databases, and methodological frameworks that underpin high-quality genome curation, with specific emphasis on applications in bacterial pathogen research.

A diverse ecosystem of databases supports the storage, retrieval, and analysis of curated bacterial genomic data. These resources vary in scope, specialization, and data access mechanisms, each contributing unique elements to the pathogen genomics research landscape. Understanding their respective strengths and appropriate use cases is fundamental for effective genomic investigation.

Major Primary Data Repositories include the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) members, which provide comprehensive archival services for raw sequence data and genome assemblies. GenBank at NCBI, the European Nucleotide Archive (EMBL-EBI), and the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) exchange data daily to ensure global coverage [28]. These repositories accept submissions with minimal curation barriers but apply standardized annotation pipelines to enhance consistency. Specialized resources like the NIH Genetic Testing Registry (GTR) and ClinVar focus specifically on clinically relevant variants, providing structured evidence frameworks for interpreting pathogenicity [29]. ClinVar has recently been updated to support classifications of both germline and somatic variants, enhancing its utility for bacterial pathogen research that differentiates between inherited characteristics and acquired mutations [28].

Value-Added and Specialized Databases apply additional layers of curation, often integrating multiple data types or focusing on specific research domains. RefSeq provides non-redundant reference sequences that leverage both computational and expert curation to produce high-quality genomic, transcript, and protein references [28]. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), an NIH-funded initiative, offers structured frameworks for evaluating gene-disease relationships and variant pathogenicity through expert panels [30]. For metagenomic-assembled genomes (MAGs), resources like MAGdb provide curated collections of high-quality MAGs with standardized metadata, specifically focusing on genomes meeting minimum information standards [31]. The database contains 99,672 high-quality MAGs with manually curated metadata from clinical, environmental, and animal sources, providing a valuable resource for discovering novel microbial lineages and understanding their ecological roles [31].

Table 1: Major Genomic Databases for Bacterial Pathogen Research

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Features | Data Volume (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GenBank | Nucleotide sequences | INSDC member, daily data exchange with ENA and DDBJ | 34 trillion base pairs, 4.7 billion sequences, 581,000 species [28] |

| RefSeq | Reference sequences | Expert curation, non-redundant, integrated with NCBI tools | Spanning tree of life [28] |

| ClinVar | Human variants | Clinical significance, supporting evidence, germline/somatic classifications | >3 million variants from >2800 organizations [28] |

| PubChem | Chemical compounds | Bioactivity data, substance-compound-bioassay relationships | 119 million compounds, 322 million substances [28] |

| MAGdb | Metagenome-assembled genomes | Quality-controlled MAGs, standardized metadata | 99,672 high-quality MAGs from 13,702 samples [31] |

Quality Control Standards and Metrics

Implementing rigorous quality control measures is paramount for ensuring the reliability of genomic data in bacterial pathogen research. The field has established standardized metrics and thresholds that differentiate high-quality genomes from those requiring additional refinement or exclusion from certain analyses.

Completeness and Contamination Assessments represent foundational quality metrics, particularly crucial for genomes derived from metagenomic assemblies or draft sequences. The Minimum Information about a Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MIMAG) standard defines high-quality MAGs as those exceeding 90% completeness while maintaining less than 5% contamination [31]. These metrics are typically assessed using conserved single-copy gene sets specific to taxonomic groups. For example, in the MAGdb repository, HMAGs (high-quality MAGs) exhibit a mean completeness of 96.84% (±2.81%) and a mean contamination rate of 1.02% (±1.09%), with genome sizes ranging from 0.52 to 12.26 Mb [31]. The relationship between sequencing depth and quality outcomes demonstrates that increased read counts generally improve both completeness and the number of recovered MAGs, though this relationship varies across sample types, with human gut and animal-derived samples showing different patterns than environmental samples [31].

Assembly Quality Metrics provide additional dimensions for evaluating genome curation outcomes. The N50 statistic, which represents the contig length at which 50% of the total assembly length is contained in contigs of equal or greater size, helps researchers assess assembly continuity. While no universal threshold exists, values exceeding 50,000 bp are often considered favorable for bacterial genomes [9]. Additionally, the presence of expected genomic features—such as complete rRNA operons, tRNAs, and conserved genomic synteny—provides biological validation of assembly quality. In comparative studies of bacterial pathogens, implementing stringent quality control procedures including CheckM evaluation with completeness ≥95% and contamination <5%, followed by genomic distance clustering (Mash distance ≤0.01), ensures a non-redundant, high-quality genome collection [9].

Table 2: Quality Control Standards for Bacterial Genome Curation

| Quality Dimension | Metric | High-Quality Standard | Assessment Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | Single-copy conserved genes | >90% (MIMAG standard) | CheckM, BUSCO |

| Contamination | Marker gene multiplicity | <5% (MIMAG standard) | CheckM |

| Assembly continuity | N50 statistic | ≥50,000 bp | Assembly metrics |

| Sequence quality | Q score | ≥Q30 | FastQC |

| Taxonomic validation | Taxonomic classification | Consistent with expected lineage | Kraken, GTDB-Tk |

| Gene space completeness | Universal single-copy orthologs | >95% | BUSCO |

Experimental Protocols for Genome Curation

Genome Assembly and Quality Control Protocol

DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Begin with high-molecular-weight DNA extraction using the CTAB method or commercial kits suitable for long-read sequencing. Assess DNA quality and integrity using a Qubit Fluorometer and NanoDrop Spectrophotometer, ensuring A260/A280 ratios of 1.8-2.0 [7]. Prepare sequencing libraries using the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit for Illumina platforms or the Template Prep Kit for Pacific Biosciences systems. Perform sequencing on both Illumina NovaSeq (2×150-bp paired-end reads) and Pacific Biosciences platforms to generate hybrid data for optimal assembly [7].

Data Preprocessing and Assembly: Remove adapter contamination and filter low-quality reads using AdapterRemoval and SOAPec (k-mer sizes of 17) [7]. Assemble filtered reads using multiple approaches: SPAdes and A5-miseq for Illumina data, and Flye and Unicycler with default settings for PacBio data [7]. Integrate all assembled results to generate a complete sequence, then rectify the genome assembly using Pilon software to correct base errors and fill gaps [7].

Quality Assessment: Evaluate assembly quality using CheckM with thresholds of ≥95% completeness and <5% contamination for inclusion in downstream analyses [9]. Calculate genomic distances using Mash and perform clustering through Markov clustering, removing bacterial genomes with genomic distances ≤0.01 to ensure non-redundancy [9]. Validate taxonomic classification by comparing assigned taxonomy with phylogenetic placement based on universal single-copy genes.

Genome Curation Workflow

Genome Annotation and Functional Analysis Protocol

Structural Annotation: Predict open reading frames (ORFs) using Prokka v1.14.6 or GeneMarkS v4.32 [9] [7]. Identify tRNA genes with tRNAscan-SE and rRNA genes using Barrnap [7]. Detect non-coding RNAs by comparison with the Rfam database, and identify CRISPR arrays using CRISPR finder [7].

Functional Annotation: Perform hierarchical annotation using multiple databases. Conduct BLAST searches against the Nonredundant Protein Database and Swiss-Prot with an e-value threshold of 1e-5 [7]. Map ORFs to the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST with an e-value threshold of 0.01 and minimum coverage of 70% [9]. Annotate carbohydrate-active enzymes using dbCAN2 to map ORFs to the CAZy database, filtering with hmm_eval 1e-5 and retaining only HMMER annotations [9].

Pathogenicity Assessment: Identify virulence factors using the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) and antimicrobial resistance genes via the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) [9]. Annotate pathogenicity islands using IslandViewer 4 and prophages with PhiSpy [7]. For comparative genomic analyses, employ pan-genome analysis approaches using tools such as Roary, and identify orthologous groups for phylogenetic reconstruction [5].

Integration and Curation: Manually review automated annotations for key pathogenicity factors, confirming functional predictions through domain architecture analysis and literature review. Submit curated genomes to public repositories following domain-specific standards, ensuring complete metadata annotation including isolation source, host information, and antimicrobial resistance profiles.

Computational Tools and Databases: The field of bacterial genome curation relies on a sophisticated ecosystem of computational resources for annotation, analysis, and data retrieval. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) provides an extensive suite of databases including GenBank, RefSeq, and ClinVar, which collectively offer curated genomic information and standardized annotation [28] [29]. Specialized functional databases like the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) and the Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database (CAZy) enable prediction of gene function and metabolic capabilities [9]. For quality assessment, tools such as CheckM and BUSCO provide essential metrics for evaluating assembly completeness and contamination, while GTDB-Tk offers standardized taxonomic classification [31].

Laboratory and Bioinformatics Reagents: Wet laboratory components of genome curation depend on high-quality molecular biology reagents and sequencing platforms. DNA extraction typically employs the CTAB method or commercial kits specifically validated for microbial genomics [7]. Library preparation utilizes standardized kits such as the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit for Illumina platforms or the Template Prep Kit for Pacific Biosciences systems [7]. For functional validation of curated genomic information, cell culture reagents including Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) enable cell adhesion and invasion assays using models like Caco-2 and RAW264.7 cells [7].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Genome Curation

| Category | Resource/Reagent | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq | Short-read sequencing | 2×150-bp paired-end reads [7] |

| Pacific Biosciences | Long-read sequencing | Improved assembly continuity [7] | |