Comparative Analysis of Niche-Associated Signature Genes: From Genomic Insights to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review explores the identification, validation, and application of niche-associated signature genes across biological systems.

Comparative Analysis of Niche-Associated Signature Genes: From Genomic Insights to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the identification, validation, and application of niche-associated signature genes across biological systems. We examine how pathogens and cells develop unique genomic signatures through adaptation to specific ecological niches or physiological conditions, highlighting key methodological approaches from comparative genomics and machine learning. The article addresses critical challenges in signature reproducibility and specificity while presenting comparative analyses of signature performance across different technologies and biological contexts. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides a framework for understanding how niche-specific gene signatures can inform therapeutic targeting, diagnostic development, and precision medicine strategies in biomedical research.

Defining Niche-Associated Signature Genes: Biological Significance and Discovery Approaches

Gene expression signatures (GES) represent unique patterns of gene activity that serve as molecular fingerprints of cellular state, physiological processes, and pathological conditions. These signatures provide critical insights into biological adaptation across diverse contexts, from microbial niche specialization to cancer evolution and host-pathogen interactions. This review synthesizes current understanding of GES conceptual frameworks, their computational derivation, and experimental validation, with emphasis on their role in adaptive processes. We systematically compare signature performance across biological contexts and methodologies, highlighting how integrative multi-omics approaches are transforming our ability to decode adaptation mechanisms. The article further presents standardized workflows for signature identification and validation, essential analytical tools, and visualization frameworks that facilitate the study of adaptation through gene expression rearrangements.

A gene expression signature is defined as a single or combined group of genes in a cell with a uniquely characteristic pattern of gene expression that occurs as a result of an altered or unaltered biological process or pathogenic medical condition [1]. Conceptually, GES capture the transcriptional output of a biological system in response to specific stimuli, developmental stages, disease states, or evolutionary pressures, providing a powerful intermediate phenotype that connects genetic variation to complex organismal traits [2].

The clinical and biological applications of gene signatures break down into three principal categories: (1) prognostic signatures that predict likely disease outcomes regardless of therapeutic intervention; (2) diagnostic signatures that distinguish between phenotypically similar medical conditions; and (3) predictive signatures that forecast treatment response and can serve as therapeutic targets [1]. Beyond clinical applications, GES have become fundamental tools for understanding evolutionary adaptation, where changes in gene regulation often underlie phenotypic diversity and niche specialization [2] [3].

The hypothesis that differences in gene regulation play a crucial role in speciation and adaptation dates back more than four decades, with King and Wilson famously arguing in 1975 that the vast phenotypic differences between humans and chimpanzees likely stem from regulatory changes rather than solely from alterations to structural proteins [2]. Contemporary research has validated this hypothesis, showing that GES provide critical insights into adaptive processes across biological scales—from microbial host-switching to primate brain evolution.

Methodological Approaches for Signature Identification

Technologies for Gene Expression Profiling

The identification of gene expression signatures relies on technologies capable of quantifying transcriptional levels across the genome. Table 1 summarizes the principal methodologies used in signature discovery and validation.

Table 1: Technologies for Gene Expression Signature Identification

| Technology | Principle | Applications in Signature Discovery | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microarrays | Hybridization of cDNA to gene probes on solid surfaces [1] | Early cancer classification [1], evolutionary studies [2] | Limited to pre-designed probes, lower dynamic range |

| RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) | High-throughput sequencing of cDNA [2] | Genome-wide signature discovery without prior sequence knowledge [2], identification of alternative splicing [2] | Broader dynamic range, identifies novel transcripts |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Positional mRNA quantification in tissue sections [4] [5] | Tumor microenvironment niche identification [4], cellular neighborhood mapping | Preserves spatial context, typically targeted gene panels |

| In Situ Hybridization (e.g., RNAscope) | Targeted RNA detection with spatial resolution [6] | Validation of signature genes in tissue context [6] | High spatial precision, limited multiplexing |

Computational and Statistical Frameworks

The derivation of robust signatures from gene expression data requires specialized computational approaches. A standard scheme for gene signature construction includes multiple stages: (1) selection of an extended list of candidate genes; (2) ranking genes according to their individual informative power using a learning set of samples with known clinical or biological annotation; and (3) selection of a classification algorithm that converts expression values into biologically or clinically relevant answers [7].

A significant challenge in signature development stems from the interconnected nature of transcriptional networks. While early approaches prioritized individually informative genes, contemporary methods recognize that "a team consisting of top players which are poorly compatible with each other is less successful than a well-knit team of individually weaker players" [7]. Thus, advanced algorithms now identify gene sets with high cumulative informative power, often discovering that small sets of genes (pairs or triples) can outperform larger signatures when selected for cooperative predictive power [7].

Machine learning approaches have enhanced signature robustness, with methods like random forests used to evaluate predictive performance [8]. Recent innovations include structural gene expression signatures (sGES) that incorporate protein structure features encoded by mRNAs in traditional GES. By representing signatures as enrichments of structural features (e.g., protein domains and folds), sGES improve reproducibility across experimental platforms and provide evolutionary insights not captured by expression patterns alone [8].

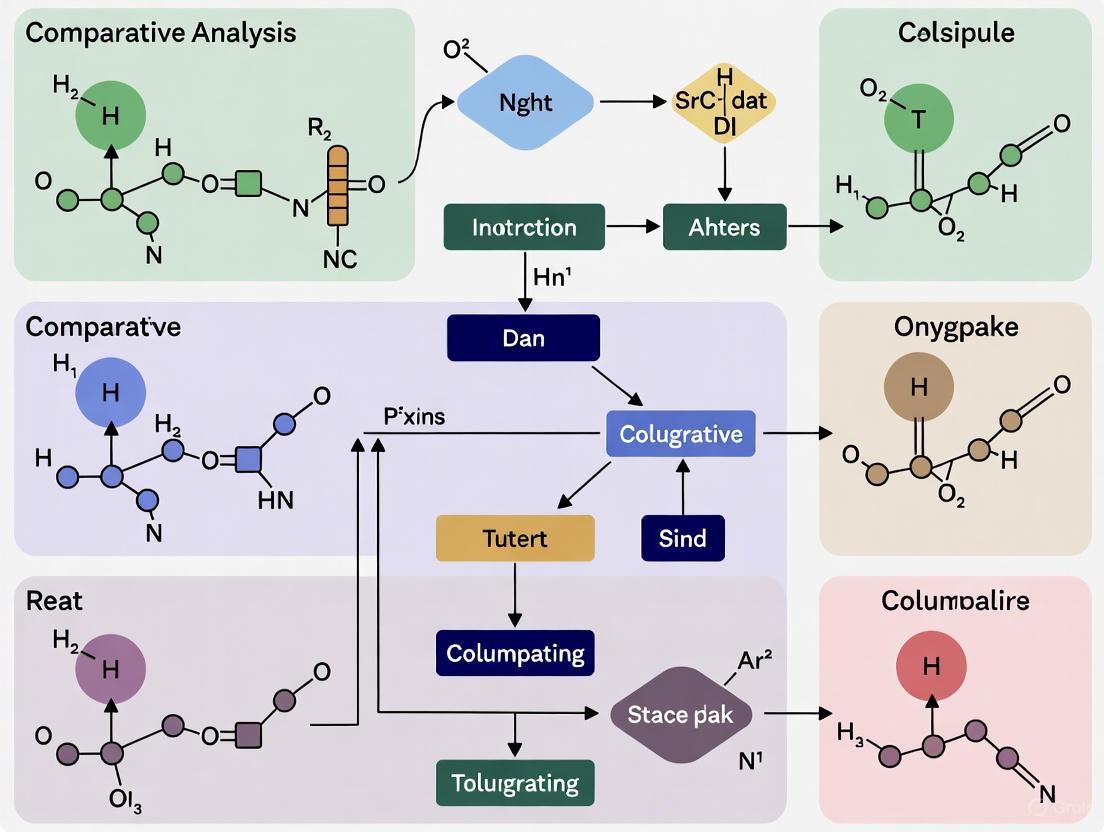

Figure 1: Workflow for Gene Expression Signature Identification and Validation

Gene Expression Signatures in Biological Adaptation

Microbial Niche Adaptation

Comparative genomic analyses of bacterial pathogens reveal distinctive gene expression signatures associated with host and environmental adaptation. In a comprehensive study of 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes, significant variability in adaptive strategies emerged across ecological niches [3]. Human-associated bacteria, particularly from the phylum Pseudomonadota, exhibited higher detection rates of carbohydrate-active enzyme genes and virulence factors related to immune modulation and adhesion, indicating co-evolution with the human host. In contrast, environmental bacteria showed greater enrichment in genes related to metabolism and transcriptional regulation, highlighting their adaptability to diverse physical and chemical conditions [3].

Microbes employ two primary genomic strategies for niche adaptation: gene acquisition through horizontal gene transfer and gene loss through reductive evolution. For example, Staphylococcus aureus acquires host-specific genes encoding immune evasion factors, methicillin resistance determinants, and metabolic enzymes through horizontal transfer [3]. Conversely, Mycoplasma genitalium has undergone extensive genome reduction, losing genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism to reallocate limited resources toward maintaining a mutualistic relationship with its host [3].

Evolutionary Adaptation in Primates

Comparative studies in primates provide compelling evidence that gene expression evolution plays a crucial role in phenotypic diversification. Research comparing humans, chimpanzees, and rhesus macaques demonstrates that the regulation of a large subset of genes evolves under selective constraint [2]. Genes with low variation in expression levels across species are likely under stabilizing selection, while lineage-specific expression patterns may indicate directional selection [2].

Notably, studies of primate brain development have identified human-specific shifts in the timing of gene expression (heterochrony) for genes with potential roles in neural development [2]. This suggests that changes in the developmental regulation of gene expression may contribute to human-specific cognitive traits, supporting the hypothesis that regulatory changes underlie morphological and functional evolution.

Cancer as an Adaptive Process

The transition from normal to cancerous tissue represents a dramatic example of biological adaptation, reflected in extensive gene expression rearrangements. Analysis of gene expression distribution functions reveals two distinct patterns of transcriptional changes during biological state transitions [9].

In continuous transitions (e.g., bacterial evolution in the Long-Term Evolution Experiment), initial and final states are relatively close in gene expression space, with only a small fraction of genes (approximately 1/200) showing significant differential expression [9]. The distribution functions show rapidly decaying tails, with most genes maintaining expression near reference values.

In contrast, discontinuous transitions (e.g., cancer development) involve radical expression rearrangements with heavy-tailed distribution functions, involving thousands of differentially expressed genes [9]. This pattern suggests initial and final states are separated by a fitness barrier, analogous to a physical phase transition.

Figure 2: Gene Expression Signatures in Adaptive Transitions

Comparative Performance of Gene Expression Signatures

Signature Robustness Across Biological Contexts

The performance of gene expression signatures varies considerably depending on signature size, biological context, and population characteristics. A systematic comparison of 28 host gene expression signatures for discriminating bacterial and viral infections revealed substantial variation in performance, with median areas under the curve (AUC) ranging from 0.55 to 0.96 for bacterial classification and 0.69-0.97 for viral classification [10].

Signature size significantly influenced performance, with smaller signatures generally performing more poorly (P < 0.04) [10]. Viral infection was easier to diagnose than bacterial infection (84% vs. 79% overall accuracy, respectively; P < .001), and classifiers performed more poorly in pediatric populations compared to adults for both bacterial (73-70% vs. 82%) and viral infection (80-79% vs. 88%) [10].

Spatial Context and Signature Specificity

Emerging spatial transcriptomics technologies reveal that gene expression signatures are tightly linked to cellular microenvironments or niches. Computational approaches like stClinic integrate spatial multi-omics data with phenotype information to identify clinically relevant niches [4]. In cancer studies, such approaches have identified aggressive niches enriched with tumor-associated macrophages and favorable prognostic niches abundant in B and plasma cells [4].

Foundation models like Nicheformer, trained on both dissociated single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data, demonstrate that models trained only on dissociated data fail to recover the complexity of spatial microenvironments [5]. This highlights the importance of incorporating spatial context when studying adaptive gene expression changes in tissue contexts.

Table 2: Factors Influencing Gene Expression Signature Performance

| Factor | Impact on Signature Performance | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Signature Size | Larger signatures generally perform better than smaller ones | P < 0.04 for size vs. performance [10] |

| Population Age | Reduced accuracy in pediatric populations vs. adults | Bacterial: 73-70% vs. 82%; Viral: 80-79% vs. 88% [10] |

| Infection Type | Viral infection easier to diagnose than bacterial | 84% vs. 79% overall accuracy (P < .001) [10] |

| Spatial Context | Dissociated data alone cannot capture spatial variation | Models without spatial training perform poorly on spatial tasks [5] |

| Technical Platform | Cross-platform reproducibility challenges require normalization | Structural GES improve cross-platform consistency [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Signature Validation

Comparative Genomic Analysis Protocol

The identification of niche-associated signature genes in bacterial pathogens follows a structured workflow [3]:

Genome Collection and Quality Control: Obtain bacterial genomes from public databases (e.g., gcPathogen). Apply stringent quality control: exclude contig-level assemblies, retain sequences with N50 ≥50,000 bp, CheckM completeness ≥95%, and contamination <5%.

Ecological Niche Annotation: Categorize genomes based on isolation source and host information into "human," "animal," or "environment" niches using standardized metadata annotations.

Phylogenetic Analysis: Identify 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome using AMPHORA2. Perform multiple sequence alignment with Muscle v5.1 and construct maximum likelihood phylogeny with FastTree v2.1.11.

Functional Annotation: Predict open reading frames with Prokka v1.14.6. Map ORFs to functional databases (COG, CAZy, VFDB, CARD) using RPS-BLAST and HMMER tools.

Signature Gene Identification: Use Scoary for pan-genome-wide association testing to identify genes significantly associated with specific niches. Apply machine learning classifiers to validate predictive power of candidate signature genes.

Spatial Niche Identification Protocol

The stClinic pipeline for identifying clinically relevant cellular niches from spatial multi-omics data involves [4]:

Data Integration: Combine spatial transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and mass spectrometry imaging data from multiple tissue slices.

Graph-Based Modeling: Model omics profiling data from multi-slices as a joint distribution p(X,A,z,c), where X represents omics data, A is an adjacency matrix, z represents batch-corrected features, and c denotes clusters within a Gaussian Mixture Model.

Dynamic Graph Learning: Employ a variational graph attention encoder (VGAE) to transform X and A into z on a Mixture-of-Gaussian manifold. Construct adjacency matrix by incorporating spatial nearest neighbors within each slice and feature-similar neighbors across slices.

Iterative Refinement: Mitigate influence of false neighbors by iteratively removing links between spots from different GMM components.

Clinical Correlation: Represent each slice with a niche vector using attention-based statistical measures (mean, variance, maximum, and minimum of UMAP embeddings, plus proportional representations). Link clusters to clinical outcomes through linear models.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Gene Expression Signature Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Application in Signature Research |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Databases | NCBI GEO [1] [7], TCGA [7] [9], GTEx [8], ARCHS4 [8] | Source of validated expression profiles for signature discovery and meta-analysis |

| Pathway Analysis | COG [3], CAZy [3], KEGG, Reactome | Functional annotation of signature genes and pathway enrichment analysis |

| Virulence Factors | VFDB [3] | Annotation of virulence-associated genes in pathogenic adaptations |

| Antibiotic Resistance | CARD [3] | Identification of resistance genes in microbial signature profiles |

| Spatial Analysis | stClinic [4], Nicheformer [5], CellCharter [4] | Identification of spatially resolved gene expression niches |

| Structural Annotation | SCOPe [8], InterProScan [8] | Protein structure feature assignment for structural GES |

| Computational Frameworks | Scoary [3], sigQC [8], Set2Gaussian [8] | Signature quality control, association testing, and robustness evaluation |

Gene expression signatures provide a powerful conceptual framework for understanding biological adaptation across diverse contexts. These signatures serve as quantitative markers that reflect strategic evolutionary responses—from microbial niche specialization to host-pathogen co-evolution and cancer progression. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that robust signature identification requires careful consideration of technological platforms, computational methodologies, and biological contexts.

While challenges remain in signature reproducibility and cross-platform validation, emerging approaches—including structural GES, spatial multi-omics integration, and foundation models—are enhancing our ability to extract biologically meaningful signals from transcriptional data. As these methodologies mature, gene expression signatures will play an increasingly important role in decoding adaptive mechanisms, with applications spanning basic evolutionary biology, infectious disease management, and precision oncology.

The evolutionary arms race between hosts and pathogens is a fundamental driver of genomic diversification. This dynamic process, shaped by the distinct ecological niches organisms inhabit, leaves characteristic signatures on their genomes. The study of these niche-associated signature genes provides a powerful lens through which to understand the mechanisms of adaptation, co-evolution, and disease emergence. For researchers and drug development professionals, deciphering these signatures is crucial for predicting pathogen transmission, understanding the genetic basis of host susceptibility, and identifying novel therapeutic targets. This guide objectively compares the primary research strategies and analytical frameworks used to identify and validate these genomic signatures, synthesizing experimental data and methodologies from contemporary studies to illuminate the complex interplay between ecological niches and genome evolution.

Comparative Analysis of Genomic Diversification Drivers

The genomic diversification of hosts and pathogens is influenced by a confluence of factors, with niche-specific selective pressures playing a predominant role. The table below summarizes the primary drivers and their documented effects across different study systems.

Table 1: Key Drivers of Genomic Diversification in Host-Pathogen Systems

| Driver | Documented Genomic Effect | Study System | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antagonistic Coevolution | Expansion of conditions for general resistance (G) evolution; maintenance of polymorphism at specific (S) resistance loci [11]. | Silene vulgaris plant model [11]. | Two-locus model showing coevolution increases genetic diversity and alters resistance correlations. |

| Niche-Specific Mutagen Exposure | Distinct single base substitution (SBS) mutational signatures correlated with replication niche [12]. | 84 clades from 31 bacterial species (e.g., Campylobacter jejuni, E. coli) [12]. | Decomposition of mutational spectra; identification of niche-associated SBS signatures (e.g., Bacteria_SBS series). |

| Spatial Population Structure | Higher resistance diversity in well-connected host populations; increased vulnerability in isolated populations [13]. | Plantago lanceolata and pathogen Podosphaera plantaginis [13]. | Inoculation assays and spatial Bayesian modelling of ~4000 host populations. |

| Niche Adaptation Strategy | Gene acquisition (e.g., Pseudomonadota) vs. genome reduction (e.g., Actinomycetota); variability in CAZymes, VFs, and ARGs [14]. | Comparative genomics of 4,366 bacterial pathogens from human, animal, and environmental niches [14]. | Functional annotation (COG, VFDB, CARD) and machine learning identifying niche-specific enrichment. |

| Host-Driven Evolutionary Pressure | Genomic variability in CAZymes, bacteriocin clusters, CRISPR-Cas systems, and antibiotic resistance genes [15]. | Limosilactobacillus reuteri from animal, human, and food sources [15]. | Pan-genome analysis of 176 genomes; phylogenetic clustering by source. |

Experimental Protocols for Identifying Niche-Associated Signatures

Comparative Genomic Analysis of Bacterial Pathogens

This protocol outlines the large-scale comparative genomics approach used to identify niche-specific adaptive mechanisms across thousands of bacterial genomes [14].

- Genome Dataset Curation: Collect a high-quality, non-redundant set of bacterial genomes with detailed metadata on isolation source and host.

- Quality Control & Niche Labeling: Implement stringent quality control (e.g., CheckM completeness ≥95%, contamination <5%). Annotate genomes with ecological niche labels ("human", "animal", "environment") based on isolation source metadata [14].

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Identify 31 universal single-copy genes in each genome. Generate multiple sequence alignments for each, concatenate alignments, and construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree [14].

- Functional Annotation:

- Gene Prediction: Use tools like Prokka to predict Open Reading Frames (ORFs).

- Functional Categorization: Map ORFs to the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST.

- Specialized Annotation: Annotate carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) with dbCAN2, virulence factors (VFs) with VFDB, and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) with the CARD database [14].

- Enrichment & Statistical Analysis: Perform enrichment analyses to identify functions, VFs, and ARGs over-represented in specific niches. Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., Scoary) to identify robust niche-associated signature genes [14].

Mutational Spectra Analysis and Niche Inference

This methodology leverages natural mutational patterns to infer the replication niche of bacterial pathogens, based on the concept that mutational signatures are associated with specific DNA repair defects or mutagen exposures [12].

- Mutational Spectrum Reconstruction: Use a bioinformatic tool (e.g., MutTui) to analyze whole-genome sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees. Reconstruct the single base substitution (SBS) mutational spectrum for each bacterial clade, rescaling by genomic nucleotide composition for comparability [12].

- Signature Extraction via NMF: Apply Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) to the collection of SBS spectra to deconvolute them into a set of fundamental, context-specific mutational signatures (e.g., Bacteria_SBS1-24) [12].

- Signature Attribution: Correlate extracted signatures with known biological processes by analyzing hypermutator lineages with known defects in DNA repair genes (e.g., mutY, mutT, ung). This links specific mutational patterns to defective DNA repair pathways [12].

- Niche Association: Statistically compare the activity of different mutational signatures between clades known to replicate in different environments (e.g., gut vs. soil). Signatures consistently active in a particular environment are classified as niche-associated [12].

- Niche Prediction: For a pathogen of unknown transmission route, reconstruct its mutational spectrum and decompose it using the reference set of signatures. The presence and contribution of known niche-associated signatures can be used to infer its predominant replication site [12].

Modeling Host-Pathogen Coevolution

This protocol describes the use of a two-locus model to investigate how coevolution shapes the evolution of general and specific resistance in hosts [11].

- Model Formulation: Develop a compartmental model with haploid hosts possessing two loci: one for general resistance (G/g) and one for specific resistance (S/s). The endemic pathogen has two genotypes: avirulent (Avr, sensitive to both resistances) and virulent (vir, evades specific resistance) [11].

- Parameter Definition:

- Resistance Benefits: Assign transmission reduction values for general resistance ((rG)), specific resistance ((rS)), and foreign pathogen reduction ((rf)).

- Resistance Costs: Assign fecundity costs for general ((cG)) and specific ((cS)) resistance alleles, which interact multiplicatively [11].

- Pathogen Evolution: Include a mutation rate for the pathogen to evolve from avirulent (Avr) to virulent (vir), which carries a potential cost ((rv)) [11].

- Simulation & Analysis: Run the model under varying conditions of resistance costs, strength of resistance, and recombination rates between the two host loci. Track the frequency of host genotypes and pathogen genotypes over time [11].

- Output Measurement: Quantify the correlation between resistance to the endemic pathogen and resistance to a foreign pathogen ("transitivity") across host genotypes. Assess the conditions that maintain polymorphisms at both resistance loci and promote the evolution of general resistance [11].

Visualizing Pathways and Workflows

Host Resistance Locus Dynamics in Coevolution

The following diagram illustrates the core logic of the two-locus host-pathogen coevolution model and the fitness outcomes for different host genotypes [11].

Niche-Specific Mutational Signature Analysis Workflow

This flowchart outlines the bioinformatic process for reconstructing mutational spectra and identifying niche-associated signatures from bacterial genomic data [12].

Spatial Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics of Host Resistance

This diagram summarizes the key findings and logical relationships regarding how spatial structure influences host resistance and pathogen impact [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents, databases, and computational tools essential for conducting research in niche-associated genomic signature discovery.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Genomic Signature Analysis

| Research Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) Database | Database | Functional categorization of predicted genes from genomic sequences [14]. | Comparing functional capabilities of bacteria from different niches (human vs. environmental) [14]. |

| Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) | Database | Repository of known virulence factors (VFs) for annotating pathogen genomes [14]. | Identifying enrichment of immune evasion or adhesion VFs in human-associated bacteria [14]. |

| Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) | Database | Catalog of antibiotic resistance genes, proteins, and mutants for annotation [14]. | Profiling abundance and diversity of ARGs in clinical vs. animal-derived bacterial isolates [14]. |

| dbCAN2 & CAZy Database | Database | Resource for annotating carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in genomes [14]. | Revealing niche-specific adaptations in metabolic capabilities, e.g., gut vs. environmental bacteria [14]. |

| MutTui | Bioinformatics Tool | Reconstructs mutational spectra from WGS alignments and phylogenetic trees [12]. | Decomposing bacterial mutational profiles to identify underlying signatures of DNA repair defects or niche-specific mutagens [12]. |

| Enrichr | Bioinformatics Tool / Database | Gene set enrichment analysis web resource for functional interpretation of gene lists [16]. | Identifying enriched Gene Ontology terms or KEGG pathways among niche-specific gene sets [16]. |

| Scoary | Bioinformatics Tool | Pan-genome-wide association study tool to identify genes associated with a bacterial phenotype [14]. | Efficiently identifying genes significantly associated with adaptation to a specific ecological niche (e.g., human host) [14]. |

| Artificial Spot Generation (NicheSVM) | Computational Method | Creates synthetic spatial transcriptomics data by combining single-cell expression profiles [16]. | Training machine learning models to deconvolute true spatial data and identify niche-specific gene expression [16]. |

The genomic diversity of bacterial pathogens is a cornerstone of their exceptional capacity to colonize and infect a wide range of hosts across diverse ecological niches [3]. Understanding the genetic basis and molecular mechanisms that enable these pathogens to adapt to different environments and hosts is essential for developing targeted treatment and prevention strategies, a priority underscored by the World Health Organization's integrative One Health approach [3]. Comparative genomics, the comparison of genetic information within and across organisms, has emerged as a powerful tool to systematically explore the evolution, structure, and function of genes, proteins, and non-coding regions [17]. This field provides critical insights into how pathogens evolve under niche-specific selection pressures, primarily through two dominant, contrasting strategies: gene acquisition via horizontal gene transfer and genome reduction through gene loss [3] [18] [19]. This guide objectively compares these adaptive strategies, providing a detailed analysis of their mechanisms, functional consequences, and prevalence across different bacterial groups, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to ongoing niche-associated signature gene research.

Core Adaptive Mechanisms: Acquisition and Reduction

Bacteria adapt to their host environment primarily through gene acquisition and gene loss [3]. These processes are influenced by distinct evolutionary pressures and result in characteristic genomic footprints.

Gene Acquisition (Expansive Adaptation): Horizontal gene transfer is common among host-associated microbiota and allows for the rapid acquisition of new functional traits [3] [20]. This strategy is exemplified by Staphylococcus aureus, which has acquired a variety of host-specific genes, including immune evasion factors in equine hosts, methicillin resistance determinants in human-associated strains, heavy metal resistance genes in porcine hosts, and lactose metabolism genes in strains adapted to dairy cattle [3]. This mechanism enables bacteria to rapidly expand their functional capabilities and virulence in new niches.

Genome Reduction (Reductive Adaptation): Also known as genome degradation, genome reduction is the process by which a genome shrinks relative to its ancestor [21]. This is not a random process but is driven by a combination of relaxed selection for genes superfluous in the host environment, a universal mutational bias toward deletions, and genetic drift resulting from small population sizes, low recombination rates, and high mutation rates [18] [19] [21]. The most extreme cases of genome reduction are observed in obligate endosymbionts and intracellular pathogens, such as Buchnera aphidicola and Mycobacterium leprae, which can lose as much as 90% of their genetic material after transitioning from a free-living to an obligate intracellular lifestyle [21]. This streamlining process can enhance metabolic efficiency and optimize resource allocation in stable environments.

Table 1: Characteristics of Genomic Adaptation Strategies

| Feature | Gene Acquisition Strategy | Genome Reduction Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) | Gene loss via deletional bias and genetic drift |

| Evolutionary Driver | Selection for new functions/virulence | Relaxed selection & genomic streamlining |

| Typical Niche | Variable or new environments | Stable, nutrient-rich host environments |

| Genomic Outcome | Larger, more dynamic genomes | Smaller, streamlined genomes |

| Functional Result | Expanded functional repertoire | Loss of redundant catabolic/biosynthetic pathways |

| Example Organisms | Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonadota | Mycoplasma genitalium, SAR11 clade, Buchnera aphidicola |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Genomic Analysis

Identifying the specific genes responsible for niche adaptation requires robust comparative approaches to differentiate core genome content from niche-specific adaptations. The following methodology, derived from a large-scale study analyzing 4,366 high-quality bacterial genomes, outlines a standard workflow for such investigations [3].

Genome Dataset Curation and Quality Control

The initial phase involves constructing a high-quality, non-redundant genome collection. This requires stringent quality control procedures:

- Source Data Retrieval: Obtain metadata and genome sequences from dedicated databases (e.g., gcPathogen).

- Initial Quality Filtering: Retain only high-quality genome sequences based on metrics such as N50 (e.g., ≥50,000 bp) and CheckM evaluations (e.g., completeness ≥95% and contamination <5%).

- Niche Annotation: Annotate genomes with ecological niche labels (e.g., human, animal, environment) based on isolation source and host metadata.

- Redundancy Removal: Calculate genomic distances using tools like Mash and perform clustering (e.g., Markov clustering) to remove redundant genomes (e.g., those with genomic distances ≤0.01).

- Taxonomic Verification: Identify and exclude sequences where taxonomic information conflicts with phylogenetic placement.

Phylogenetic and Population Structure Analysis

To control for phylogenetic relatedness and identify characteristic genes within clades:

- Marker Gene Identification: Retrieve a set of universal single-copy genes (e.g., 31 genes using AMPHORA2) from each genome.

- Sequence Alignment and Tree Construction: Generate multiple sequence alignments for each marker gene (e.g., using Muscle) and concatenate them into a single alignment. Construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using software like FastTree.

- Population Clustering: Convert the phylogenetic tree into an evolutionary distance matrix and perform clustering (e.g., k-medoids clustering using the R package

cluster) to define populations for within-clade comparisons.

Functional and Pathogenic Annotation

This step links genomic data to functional potential.

- Open Reading Frame (ORF) Prediction: Use tools like Prokka for genome annotation and ORF prediction.

- Functional Categorization: Map predicted ORFs to functional databases such as the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST.

- Specialized Enzyme Annotation: Annotate carbohydrate-active enzyme genes using the dbCAN2 tool and the CAZy database.

- Pathogenic Mechanism Annotation: Interrogate virulence factors using the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) and antibiotic resistance genes using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD).

Identification of Niche-Associated Signature Genes

The final phase involves statistical and machine learning approaches to pinpoint adaptive genes.

- Association Analysis: Use tools like Scoary to perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for identifying genes correlated with specific ecological niches.

- Machine Learning Validation: Apply machine learning algorithms to validate the predictive accuracy of identified niche-associated signature genes.

Comparative Analysis of Niche-Specific Genomic Features

Large-scale comparative genomic studies of pathogens from human, animal, and environmental sources reveal distinct, quantifiable differences in their genomic content and functional profiles, directly reflecting their adaptive strategies [3].

Quantitative Genomic Profiles Across Niches

Table 2: Niche-Associated Genomic and Functional Profiles

| Ecological Niche | Representative Phyla | Enriched Gene Categories | Key Adaptive Traits | Dominant Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human-Associated | Pseudomonadota | Higher rates of carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZy) genes; Virulence factors (immune modulation, adhesion) | Co-evolution with host; Immune evasion; Adhesion | Gene Acquisition |

| Clinical Settings | Various (e.g., Pseudomonadota, Bacillota) | High enrichment of antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., fluoroquinolone resistance) | Multidrug resistance; Treatment failure | Gene Acquisition |

| Animal-Associated | Various | Significant reservoirs of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes | Zoonotic transmission potential; Reservoir for resistance | Mixed (Acquisition & Reduction) |

| Environmental | Bacillota, Actinomycetota | Metabolism and transcriptional regulation; Nutrient scavenging | High metabolic flexibility; Environmental sensing | Genome Reduction (e.g., in free-living SAR11) |

| Obligate Intracellular/Symbiotic | Bacillota (e.g., Buchnera) | Drastic loss of biosynthetic and stress response genes; Retention of essential nutrient provisioning | Genome streamlining; Host dependence; Mutualism | Extreme Genome Reduction |

Functional Consequences of Genome Reduction

Genome reduction profoundly alters the functional constraints on the genes that remain. One key consequence is the evolution of protein multitasking or moonlighting, where surviving proteins adopt new roles to counteract gene loss [18]. Comparisons of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks in bacteria with varied genome sizes reveal that proteins in small genomes interact with partners from a wider range of functions than their orthologs in larger genomes, indicating an increase in functional complexity per protein [18]. For instance, Mycobacterium tuberculosis lacks a functional α-ketogluanine dehydrogenase but maintains a functional TCA cycle because another protein, the multifunctional α-ketoglutarate decarboxylase (KGD), has assumed this compensatory role [18].

Successful comparative genomics research relies on a suite of publicly available databases, software tools, and computational resources. The following table details essential solutions for conducting studies on niche-specific adaptation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Genomics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Niche Adaptation Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| COG Database | Functional Database | Classification of proteins into Orthologous Groups | Core functional categorization; Identifying conserved vs. variable functions [3] |

| dbCAN2 / CAZy | Functional Database | Annotation of Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes | Identifying adaptations to host carbohydrate diets [3] |

| VFDB | Specialized Database | Catalog of Virulence Factors | Annotating virulence mechanisms enriched in host-associated pathogens [3] |

| CARD | Specialized Database | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Gene Catalog | Identifying resistance genes enriched in clinical settings [3] |

| MutTui | Bioinformatics Tool | Reconstruction of mutational spectra from alignments | Identifying niche-specific mutational signatures and DNA repair defects [22] |

| Scoary | Bioinformatics Tool | Pan-genome-wide association study (Pan-GWAS) | Identifying genes associated with specific ecological niches [3] |

| Prokka | Bioinformatics Tool | Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation | Standardized ORF prediction as a prerequisite for functional analysis [3] |

| CheckM | Bioinformatics Tool | Assess genome quality & completeness | Essential for quality control during dataset curation [3] |

| AMPHORA2 | Bioinformatics Tool | Identification of phylogenetic marker genes | Sourcing single-copy genes for robust phylogenetic tree construction [3] |

| NIH CGR | Resource Platform | NIH Comparative Genomics Resource | Access to curated eukaryotic genomic data and analysis tools [17] |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows in Genomic Adaptation

The interplay between environmental pressure, mutagenesis, and DNA repair shapes the mutational spectra of bacterial pathogens, creating distinctive signatures associated with their replication niches. Furthermore, the contrasting adaptive strategies of acquisition and reduction can be visualized as divergent evolutionary pathways.

Mutational Signature Extraction and Niche Inference

Recent research demonstrates that mutational spectra, which are composites of mutagenesis and DNA repair, can be decomposed into specific mutational signatures driven by distinct defects in DNA repair or by exposure to niche-specific mutagens [22]. This process allows researchers to infer the predominant replication niches of bacterial clades.

Evolutionary Pathways of Genomic Adaptation

Bacteria follow distinct evolutionary trajectories based on their environmental stability and exposure to foreign genetic material. This divergence leads to the two primary adaptive strategies compared in this guide.

The comparative analysis of niche-specific signature genes unequivocally demonstrates that bacterial pathogens employ two dominant, contrasting genomic strategies for adaptation: gene acquisition and genome reduction. The choice of strategy is fundamentally dictated by the ecological niche. Gene acquisition, prevalent in variable environments like human and animal hosts, facilitates rapid expansion of functional capabilities, including virulence and antibiotic resistance. In contrast, genome reduction, a hallmark of stable environments such as those of obligate intracellular symbionts or nutrient-poor free-living habitats, optimizes efficiency through streamlining and protein multitasking. The experimental protocols, datasets, and bioinformatics tools detailed in this guide provide a robust framework for researchers to continue deciphering the genetic basis of host-pathogen interactions. These insights are critical for informing public health initiatives, from predicting pathogen emergence and transmission routes to developing novel antimicrobial therapies that target niche-specific adaptive pathways.

Understanding the genetic determinants that enable bacterial pathogens to adapt to specific niches is a fundamental pursuit in microbial genomics and infectious disease research. The evolutionary divergence between bacteria that thrive in the human host and those that persist in environmental reservoirs is orchestrated by distinct selective pressures that shape their genomic architecture [3]. This comparative analysis delves into the realm of niche-associated signature genes, exploring the specialized genetic repertoires that underpin survival strategies in human-associated versus environmental bacterial pathogens.

The study of these signature genes extends beyond academic interest, providing crucial insights for public health interventions, antibiotic stewardship, and the prediction of emerging pathogenic threats [23]. By examining the genetic signatures of adaptation, researchers can unravel the molecular dialogue between pathogens and their habitats, revealing how environmental microbes acquire the capacity to colonize human hosts and how human-adapted pathogens optimize their fitness within the host ecosystem [3]. This review synthesizes findings from contemporary genomic studies to objectively compare the genetic signatures that define bacterial lifestyles across the human-environment spectrum, framing this analysis within the broader thesis of niche adaptation research.

Methodological Framework for Comparative Genomic Analysis

Genome Dataset Curation and Quality Control

The foundation of robust comparative genomics lies in the construction of high-quality, non-redundant genome datasets. The exemplary protocol from a large-scale study analyzed 1,166,418 human pathogens from the gcPathogen database, implementing stringent quality filters to ensure data integrity [3]. The curation process involves multiple critical steps, summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Genome Dataset Curation Protocol

| Processing Step | Quality Control Parameters | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Metadata Filtering | Exclusion of contig-level assemblies; Retention based on N50 ≥50,000 bp | Initial quality screening |

| CheckM Evaluation | Genome completeness ≥95%; Contamination <5% | Assessment of assembly quality |

| Ecological Niche Annotation | Labeling based on isolation source (Human, Animal, Environment) | Functional classification for comparison |

| Redundancy Reduction | Mash distance calculation ≤0.01 with Markov clustering | Non-redundant genome collection |

| Taxonomic Verification | Phylogenetic consistency check | Final validation of 4,366 genomes |

This meticulous process ensures that subsequent analyses are built upon a reliable genomic foundation, minimizing artifacts that could compromise the identification of true signature genes [3].

Phylogenetic and Functional Annotation Pipelines

Following genome curation, phylogenetic reconstruction establishes an evolutionary framework for comparative analyses. Using tools like AMPHORA2, researchers identify 31 universal single-copy genes from each genome to construct a robust maximum likelihood tree [3]. This phylogenetic framework enables the differentiation of conserved core genomes from lineage-specific or niche-specific genetic elements.

Functional annotation involves multiple complementary approaches:

- Open reading frame (ORF) prediction using Prokka [3]

- Functional categorization via Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database using RPS-BLAST [3]

- Carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation with dbCAN2 against the CAZy database [3]

- Virulence factor identification through the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB)

- Antibiotic resistance gene profiling via the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)

This multi-layered annotation strategy enables researchers to move beyond mere gene identification to understanding potential functional implications in niche adaptation.

Statistical and Machine Learning Approaches for Signature Identification

Advanced computational methods are essential for distinguishing statistically significant signature genes from background genetic variation. The Scoary algorithm is frequently employed to identify genes associated with specific ecological niches through pan-genome-wide association studies [3]. This method correlates gene presence/absence patterns with phenotypic traits—in this case, isolation source.

Machine learning approaches, particularly Random Forests classifiers, have demonstrated utility in building predictive models that can classify bacterial genomes according to their ecological origin based on genetic signatures [24]. These methods inherently perform feature selection, helping to identify the most discriminative genetic markers for human-associated versus environmental lifestyles.

Table 2: Key Analytical Tools for Signature Gene Discovery

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Application in Niche Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Scoary | Pan-genome-wide association studies | Identifies genes correlated with isolation source |

| Random Forests | Machine learning classification | Discovers discriminative genetic markers for ecological niches |

| Global Test | Gene set analysis | Tests association between gene sets and phenotypic variables |

| UVE-PLS | Multivariate regression with variable selection | Correlates allele frequencies with environmental factors |

Furthermore, Gene Set Analysis (GSA) methods, such as the Global Test, assess whether sets of genes (signatures) show significant association with specific environmental variables or phenotypes, moving beyond single-gene analyses to pathway-level insights [25].

Comparative Analysis of Signature Genes Across Niches

Genomic Features of Human-Associated Bacterial Pathogens

Bacteria isolated from human hosts exhibit distinctive genomic signatures reflective of co-evolution with the human immune system and physiological environment. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that human-associated bacteria, particularly those from the phylum Pseudomonadota, display significantly higher abundances of carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZy) genes and specialized virulence factors related to immune modulation and host adhesion [3].

These pathogens have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for host interaction, including:

- Immune evasion genes that enable persistence in immunocompetent hosts

- Adhesion factors facilitating mucosal colonization

- Metabolic adaptation to human-specific nutrient sources

- Toxin production systems that damage host tissues

A key finding from recent research is the identification of specific signature genes like hypB, which appears to play a crucial role in regulating metabolism and immune adaptation in human-associated bacteria [3]. This gene represents a potential target for understanding the genetic basis of host specialization.

Genomic Features of Environmental Bacterial Pathogens

Environmental bacteria, particularly those from the phyla Bacillota and Actinomycetota, exhibit genomic signatures of generalist survival strategies. These microbes show greater enrichment in genes related to metabolic versatility and transcriptional regulation, highlighting their need to rapidly adapt to fluctuating environmental conditions [3].

Environmental pathogens typically possess:

- Diverse catabolic pathways for breakdown of complex substrates

- Stress response systems for temperature, pH, and osmotic fluctuations

- Sporulation genes in certain taxa for dormancy and survival

- Secondary metabolite clusters for competition in microbial communities

The environmental gene repertoire reflects selective pressures geared toward resource acquisition and persistence under nutrient limitation, rather than host immune evasion. This fundamental difference in selective pressures creates distinguishable genomic signatures between environmental and human-adapted lineages.

Quantitative Comparison of Genetic Signatures

The distinct evolutionary paths of human-associated and environmental bacteria manifest in quantifiable differences in their genomic content. Table 3 summarizes key comparative findings from large-scale genomic studies.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Genomic Features Across Ecological Niches

| Genomic Feature | Human-Associated Bacteria | Environmental Bacteria | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virulence Factors (Immune Modulation) | Significantly higher | Lower | VFDB annotation |

| Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes | Higher abundance | Lower abundance | CAZy database mapping |

| Antibiotic Resistance Genes | Higher in clinical isolates | Variable, often lower | CARD database screening |

| Metabolic Pathway Genes | Specialized for host nutrients | Highly diverse for complex substrates | COG functional categorization |

| Transcription Regulation | Less enriched | Significantly enriched | COG functional categorization |

Human-associated bacteria from the phylum Pseudomonadota predominantly employ a gene acquisition strategy through horizontal gene transfer, allowing rapid adaptation to host environments by incorporating virulence factors and specialized metabolic capabilities [3]. In contrast, Actinomycetota and certain Bacillota utilize genome reduction as an adaptive mechanism, streamlining their genomes to eliminate unnecessary functions for a specialized lifestyle [3].

Experimental Validation of Signature Genes

Functional Assessment of Niche-Associated Genes

The identification of signature genes represents only the first step in understanding niche adaptation. Functional validation is essential to establish causal relationships between genetic signatures and phenotypic traits. Experimental approaches include:

- Gene knockout/complementation studies to assess necessity and sufficiency for host-specific traits

- Heterologous expression in non-adapted strains to test functional transfer

- Transcriptomic profiling under host-mimicking conditions

- Protein-protein interaction assays to map host-pathogen interfaces

For instance, the discovery of hypB as a potential human host-specific signature gene warrants functional characterization through mutagenesis followed by assessment of metabolic capabilities and immune interaction profiles [3]. Such experiments could reveal whether hypB truly serves as a master regulator of human adaptation or functions within a broader genetic network.

Pathway Mapping and Network Analysis

Signature genes do not operate in isolation but function within interconnected cellular networks. Mapping these genes onto biological pathways reveals the systems-level adaptations that distinguish human-associated from environmental pathogens. Computational approaches include:

- KEGG pathway enrichment analysis to identify overrepresented metabolic and signaling pathways

- Protein-protein interaction network mapping using databases like STRING

- Operon structure conservation analysis to infer coregulated gene sets

- Phylogenetic distribution profiling to track evolutionary origins

Studies have successfully employed transcriptomic-causal networks—Bayesian networks augmented with Mendelian randomization principles—to identify functionally related gene sets that form signatures for specific adaptations [26]. This approach moves beyond correlation to infer causal relationships within gene networks.

The diagram below illustrates a conceptual workflow for experimental validation of signature genes:

Cutting-edge research into bacterial signature genes relies on a sophisticated suite of bioinformatics tools, databases, and experimental resources. Table 4 compiles essential components of the methodological toolkit for studying niche-associated genetic adaptations.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Signature Gene Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Databases | gcPathogen, NCBI RefSeq, GEMs, UHGG | Source of curated genomic data for analysis |

| Functional Annotation | COG, dbCAN2, Pfam, eggNOG | Functional categorization of gene products |

| Specialized Databases | VFDB, CARD, CAZy | Identification of virulence, resistance, CAZyme genes |

| Phylogenetic Tools | AMPHORA2, FastTree, MUSCLE | Phylogenetic reconstruction and evolutionary analysis |

| Signature Discovery | Scoary, Random Forests, Global Test | Identification of niche-associated gene signatures |

| Pathway Analysis | KEGG, STRING, TRANSFAC | Mapping genes to biological pathways and networks |

| Experimental Validation | Gene knockout systems, Heterologous expression | Functional assessment of candidate signature genes |

This toolkit enables researchers to progress from genome sequencing to mechanistic understanding of niche adaptation. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation represents the gold standard for confirming the role of signature genes in host-environment specialization.

Implications for Public Health and Therapeutic Development

The comparative analysis of signature genes between human-associated and environmental pathogens has profound implications for public health surveillance, infection control, and therapeutic development. Understanding the genetic basis of host adaptation can inform several critical areas:

Pathogen Surveillance and Emerging Disease Prediction

Tracking the distribution of signature genes across bacterial populations enables identification of environmental strains with emergent pathogenic potential. Environmental bacteria carrying human-adaptation signatures represent pre-adapted pathogens that may require enhanced surveillance. The discovery that animal hosts serve as important reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes highlights the importance of One Health approaches that integrate human, animal, and environmental monitoring [3].

Antibiotic Stewardship and Resistance Management

The finding that clinical isolates harbor higher rates of antibiotic resistance genes, particularly those conferring fluoroquinolone resistance, underscores the selective pressure exerted by healthcare environments [3]. This knowledge can guide antibiotic stewardship programs by highlighting environments where resistance selection is most intense. Furthermore, identifying resistance genes that serve dual roles in environmental adaptation may reveal new targets for antimicrobial development.

Therapeutic Target Discovery

Signature genes essential for host adaptation represent promising targets for novel anti-infective strategies. Unlike essential genes required for viability in all environments, niche-specific signature genes may offer opportunities for targeted interventions that disrupt pathogen establishment without broadly affecting commensal microbiota. For instance, the hypB gene, identified as a human host-specific signature, warrants investigation as a potential target for anti-virulence compounds [3].

The systematic comparison of signature genes in human-associated versus environmental bacterial pathogens reveals fundamental principles of microbial evolution and adaptation. Human-associated pathogens exhibit genomic signatures of specialized interaction with the host immune system and metabolic environment, while environmental strains display genetic hallmarks of metabolic versatility and stress response capabilities.

These distinctions are not merely academic—they provide a roadmap for understanding the emergence of pathogenic lineages, predicting future disease threats, and developing targeted therapeutic interventions. The integration of large-scale genomic analyses with functional validation represents the path forward for elucidating the genetic basis of niche specialization.

As sequencing technologies advance and datasets expand, the resolution of signature gene identification will continue to improve, potentially enabling prediction of pathogenic potential from environmental isolates and personalized approaches to infection management based on the genetic profile of infecting strains. The continued investigation of niche-associated signature genes will undoubtedly yield new insights into host-pathogen evolution and novel strategies for combating infectious diseases.

The transcriptome, the complete set of RNA transcripts in a cell, is far from a static entity. It is a dynamic system that responds to developmental cues, environmental signals, and disease states. Understanding this dynamism requires moving beyond bulk tissue analysis to a cell-centric perspective, as cellular heterogeneity can mask critical biological mechanisms in pooled samples [27]. The recent advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized this field, enabling researchers to investigate gene expression with unprecedented resolution and to define cell types and states based on their intrinsic molecular profiles rather than pre-selected markers [27]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the technologies and computational methods used to unravel the dynamic transcriptome, with a specific focus on applications in studying niche-associated signature genes. We objectively compare the performance of different approaches, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting optimal strategies for their investigative goals.

Table 1: Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Technology Platforms

| Technology Platform | Throughput (Cells) | Transcriptome Coverage | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-based (e.g., Smart-seq2) [27] | Hundreds | High (Full-length) | High sensitivity, detects more genes per cell | Low throughput, higher cost per cell | In-depth characterization of homogenous or rare cells |

| Droplet-based Microfluidics (e.g., 10x Genomics) [27] [28] | Thousands | Low to Medium (3'-biased) | High scalability, cost-effective for large cell numbers | Lower genes detected per cell | Profiling complex tissues, identifying all cell types |

| Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) [27] [29] | Tens | Varies | Preserves spatial information, precise location | Very low throughput, requires fixed tissue | Analyzing cells in specific anatomical micro-niches |

| Micromanipulation [27] | Tens | High (Full-length) | Unbiased selection of large cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes) | Manual, time-consuming, operator-dependent | Isolating specific, large cells from culture or tissue |

| Valve-based Microfluidics [27] | Hundreds | Medium | Flexible reaction conditions | Requires dedicated equipment | Medium-throughput studies with controlled workflows |

Section 1: Core Technologies for Capturing Transcriptional Dynamics

The choice of technology for single-cell transcriptomics is a critical first step, dictated by the biological question. The fundamental trade-off often lies between the number of cells that can be profiled and the depth of transcriptome coverage per cell [27].

Droplet-based microfluidics, such as the 10x Genomics platform used in the laryngotracheal stenosis (LTS) study [28], excel in scalability. This method enabled the profiling of over 47,000 cells, revealing novel fibroblast subpopulations. Its high throughput is essential for deconvoluting the cellular composition of complex tissues without prior knowledge of their constituents. However, the lower coverage per cell can miss subtle transcriptional differences between similar cell states.

In contrast, plate-based methods like Smart-seq2 provide superior sensitivity and full-length transcript coverage. This is crucial for applications like alternative splicing analysis or when studying a well-defined, rare cell population where maximizing gene detection is paramount. The main drawback is lower throughput, making it less suitable for comprehensive tissue atlas projects.

For studies where spatial context is inseparable from cellular function, Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) is indispensable. It allows for the precise isolation of cells from specific tissue locations, preserving critical spatial information that is lost during tissue dissociation for other methods [27] [29]. While its throughput is the lowest, it provides a unique window into the transcriptional state of cells within their native micro-niche.

Section 2: Experimental Workflow and Protocol Details

A standard scRNA-seq experiment involves a multi-step process, from cell preparation to computational analysis. The following diagram and protocol details outline a typical workflow for a droplet-based system, as used in dynamic studies.

Diagram 1: A generalized experimental workflow for droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Single-Cell Suspension Preparation:

- Tissue Dissociation: Tissues are washed with PBS and dissected into 1 mm³ pieces. They are then digested in a tissue dissociation solution (e.g., collagenase) for 30 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation [28].

- Quality Control (QC): The resulting cell suspension is filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer and centrifuged. Cell viability is assessed using the Trypan blue exclusion method, with a viability rate of over 80% considered acceptable [28]. This step is critical, as high levels of dead cells can significantly impact data quality.

Single-Cell Capture and Library Preparation (10x Genomics Protocol):

- GEM Generation: The single-cell suspension is loaded onto a 10x Chromium chip to create Gel Beads-in-Emulsion (GEMs). Each GEM contains a single cell, a barcoded gel bead, and reverse transcription reagents [28].

- Reverse Transcription: Within the GEMs, RNA is reverse-transcribed into barcoded cDNA.

- cDNA Amplification and Library Construction: The barcoded cDNA is purified, amplified, and then enzymatically fragmented and sized before adapter ligation and PCR amplification to create the final sequencing library [28].

Sequencing and Data Processing:

- Libraries are sequenced on platforms like the Illumina NovaSeq (e.g., 150 bp paired-end reads) [28].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: The raw sequencing data is processed using tools like the 10x Genomics Cell Ranger to generate a feature-barcode matrix.

- Downstream Analysis in R/Python: The matrix is imported into analysis toolkits like Seurat for quality control (filtering cells with <500 genes or >25% mitochondrial reads), normalization, principal component analysis (PCA), and graph-based clustering. Cells are visualized using UMAP or t-SNE [28].

Section 3: Computational Methods for Decoding Dynamics from scRNA-seq Data

The true power of scRNA-seq is unlocked through computational biology, which transforms complex data into biological insights.

Trajectory Inference algorithms, such as Monocle2, use the expression data to reconstruct a "pseudotemporal" ordering of cells along a differentiation or biological process continuum [28]. This allows researchers to model the dynamic changes in gene expression as cells transition from one state to another, for instance, from a healthy fibroblast to a pro-fibrotic state, without the need for synchronized time-series samples.

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis, exemplified by tools like WGCNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis), identifies modules of genes with highly correlated expression patterns across cells [30]. This approach is powerful for detecting conserved regulatory programs across species. For example, a comparative study of limb development in chicken and mouse identified co-expression modules with varying degrees of evolutionary conservation, revealing both rapidly evolving and stable transcriptional programs in homologous cell types [30].

Genetic Modeling of Expression is an advanced method that integrates genotype data with scRNA-seq to build models that predict cell-type-specific gene expression. This framework, as applied to dopaminergic neuron differentiation, can quantify how genetic variation influences gene expression dynamically across cell types and states, providing deep insights into the context-dependent genetic regulation of disease [31].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Analysis Methods

| Method | Primary Function | Key Application in Dynamic Studies | Data Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monocle2 [28] | Pseudotime Trajectory Analysis | Models transitions (e.g., differentiation, disease progression) | scRNA-seq count matrix |

| WGCNA [30] | Gene Co-expression Network Analysis | Identifies conserved or species-specific regulatory modules | scRNA-seq count matrix (multiple samples/species) |

| Genetic Prediction Models [31] | Cell-type-specific Expression Prediction | Quantifies genetic control of expression; links to disease GWAS | scRNA-seq + matched genotype data |

| CellPhoneDB [28] | Cell-Cell Communication Analysis | Infers ligand-receptor interactions between cell clusters | scRNA-seq count matrix with cell annotations |

Section 4: Case Study - Dynamic Profiling of Airway Fibrosis

A study on Laryngotracheal Stenosis (LTS) exemplifies the power of dynamic scRNA-seq [28]. Researchers established a rat model of LTS and performed scRNA-seq on laryngotracheal tissues at multiple time points post-injury (days 1, 3, 5, and 7).

Key Findings:

- Cellular Composition Shifts: The analysis revealed a dynamic shift from an inflammatory state (high infiltration of immune cells like macrophages) at early time points to a repair/fibrotic state (dominance of fibroblasts) at later stages.

- Discovery of Novel Cell States: The study identified a previously unknown fibroblast subpopulation, termed Chondrocyte Injury-Related Fibroblasts (CIRFs), characterized by markers like Ucma and Col2a1. Trajectory analysis suggested that CIRFs may originate from the perichondrium and represent a tissue-specific lineage contributing to fibrosis.

- Macrophage Heterogeneity: Going beyond the classical M1/M2 dichotomy, the study identified specific macrophage subtypes, with SPP1+ macrophages being the predominant pro-fibrotic subpopulation in LTS.

- Cell-Cell Communication: Using CellPhoneDB, the researchers mapped the ligand-receptor interactions between SPP1+ macrophages and fibroblast subpopulations, proposing a molecular mechanism for the sustained fibrotic response.

This case demonstrates how dynamic scRNA-seq can uncover novel cell types, trace their origins, and elucidate the cellular crosstalk that underlies disease pathogenesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Dissociation Kit | Enzymatically breaks down extracellular matrix to create single-cell suspensions. | Collagenase-based solutions; critical for maintaining high cell viability [28]. |

| Cell Strainer (40 μm) | Removes cell clumps and debris to prevent microfluidic chip clogging. | A standard step in pre-processing suspensions for droplet-based systems [28]. |

| Viability Stain (Trypan Blue) | Distinguishes live from dead cells for quality control. | A viability rate >80% is typically required for robust library prep [28]. |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Chip | Part of a commercial system for partitioning single cells into nanoliter-scale droplets. | Enables high-throughput, barcoded scRNA-seq [28]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase & Master Mix | Synthesizes first-strand cDNA from RNA templates within each droplet. | A key component of the GEM reaction [28]. |

| Seurat R Toolkit | A comprehensive open-source software for QC, analysis, and exploration of scRNA-seq data. | Industry standard for single-cell bioinformatics [28]. |

| CellPhoneDB | A public repository of ligands, receptors and their interactions to infer cell-cell communication. | Used to decode signaling networks between cell clusters [28]. |

The field of dynamic transcriptomics is moving at a rapid pace, driven by technological and computational innovations. The choice between high-throughput and high-sensitivity technologies must be aligned with the specific research objective, whether it is to catalog cellular diversity in a complex organ or to perform an in-depth analysis of a specific cell state. The integration of temporal sampling with advanced computational methods like trajectory inference and gene co-expression network analysis is proving indispensable for moving from static snapshots to a cinematic understanding of biology and disease. As these tools continue to mature, they will undoubtedly uncover the full complexity of niche-associated gene signatures, paving the way for more precise and effective therapeutic interventions.

Methodological Approaches for Signature Identification and Practical Applications

This guide provides a comparative analysis of computational pipelines used to identify and analyze gene expression signatures, with a focus on their application in niche-associated signature genes research. It objectively compares the performance of various methods and supporting experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The transition from bulk differential gene expression analysis to the generation of robust, biologically meaningful signatures is a cornerstone of modern genomics. Computational pipelines are essential for transforming raw transcriptomic data into interpretable gene signatures that can predict clinical outcomes, elucidate disease mechanisms, and identify potential therapeutic targets. The field is characterized by a diverse ecosystem of tools, each employing distinct statistical learning approaches, normalization strategies, and validation frameworks. The performance of these pipelines is critical, as it directly impacts the reliability of downstream biological interpretations and clinical applications.

Current challenges include managing the complexity of large-scale gene expression data, selecting appropriate normalization methods to mitigate technical variability, and ensuring the robustness and reproducibility of identified signatures across different parameter settings and datasets. Furthermore, the emergence of spatial transcriptomics technologies has introduced new dimensions to signature generation, enabling researchers to contextualize gene expression patterns within the tissue architecture and mechanical microenvironment. This guide systematically compares several prominent pipelines, evaluating their methodologies, performance metrics, and applicability to different research scenarios in signature gene discovery.

Comparative Analysis of Signature Generation Pipelines

The table below provides a high-level comparison of several computational pipelines used for gene signature generation, highlighting their core methodologies, key performance metrics, and primary applications.

| Pipeline Name | Core Methodology | Key Performance Metrics / Findings | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGRN/PEREGGRN [32] | Supervised machine learning for forecasting gene expression from regulator inputs. | Often fails to outperform simple baselines on unseen perturbations; performance varies by metric (MAE, MSE, Spearman). | General-purpose prediction of genetic perturbation effects. |

| ICARus [33] | Independent Component Analysis (ICA) with iterative parameter exploration and robustness assessment. | Identifies reproducible signatures via stability index (>0.75) and cross-parameter clustering. | Extraction of robust co-expression signatures from complex transcriptomes. |

| Spatial Mechano-Transcriptomics [34] | Integrated statistical analysis of transcriptional and mechanical signals from spatial data. | Identifies gene modules predictive of cellular mechanical behavior; infers junctional tensions and pressure. | Linking gene expression to mechanical forces in developing tissues and cancer. |

| 8-Gene LUAD Signature [35] | WGCNA co-expression network analysis combined with ROC analysis of hub genes. | 8-gene signature achieved average AUC of 75.5% for survival prediction, comparable to larger established signatures. | Prognostic biomarker discovery for early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. |

| Spatial Immunotherapy Signatures [36] | Spatial multi-omics (proteomics/transcriptomics) with LASSO-Cox models. | Resistance signature HR=3.8-5.3; Response signature HR=0.22-0.56 for predicting immunotherapy outcomes. | Predicting response and resistance to immunotherapy in NSCLC. |

Key Performance Insights from Comparative Data

- Benchmarking Frameworks: The PEREGGRN platform, which evaluates methods like GGRN, underscores the importance of rigorous benchmarking on held-out perturbation conditions. Its finding that complex methods often fail to surpass simple baselines highlights the non-trivial nature of expression forecasting and the risk of over-optimism in method development [32].

- Signature Robustness: The ICARus pipeline addresses a critical issue in signature generation: parameter sensitivity. By iterating over a range of "near-optimal" parameters and employing a stability index, it outputs only those signatures that are reproducible, thereby increasing biological confidence [33].

- Clinical Predictive Power: The 8-gene LUAD signature demonstrates that a compact, biologically informed signature can achieve predictive power (AUC ~75.5%) comparable to larger, more complex signatures. This was achieved by focusing on hub genes from co-expression modules strongly correlated with survival and staging [35].

- Satial Multi-Omics Integration: Pipelines incorporating spatial context, such as the Spatial Immunotherapy and Mechano-Transcriptomics frameworks, show high predictive value (Hazard Ratios ranging from 0.22 to 5.3). They uniquely link gene expression to tissue-scale biology—whether mechanical forces or immune cell interactions—providing insights that bulk sequencing cannot [34] [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for implementation, this section details the experimental protocols and workflows for the featured pipelines.

Workflow for Robust Gene Signature Extraction using ICARus

The ICARus pipeline is designed for the robust and reproducible extraction of gene expression signatures from transcriptomic datasets using Independent Component Analysis (ICA). The following diagram illustrates its key stages.

Protocol Steps [33]:

- Input Data Preparation: Provide a normalized transcriptome matrix (e.g., using CPM or Ratio of median) with genes as rows and samples as columns. Pre-filtering of sparsely expressed genes is recommended.

- Parameter Range Estimation:

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the input dataset.

- Use the Kneedle algorithm on the standard deviation elbow plot or cumulative variance knee plot from PCA to determine the lower bound

nfor the number of components. - Define the near-optimal parameter set as all integers from

nton + k(wherekis user-defined, default is 10).

- Intra-Parameter Robustness Analysis:

- For each parameter

nin the set, run the ICA algorithm 100 times. - Perform sign correction and hierarchical clustering on the resulting signatures.

- For each cluster, calculate the stability index using the Icasso method. Extract the medoid signature from clusters with a stability index > 0.75.

- For each parameter

- Inter-Parameter Reproducibility Assessment:

- Cluster all robust signatures (from all

nvalues) together. - Identify signature clusters that contain signatures derived from multiple different

nvalues within the near-optimal set. These are deemed reproducible.

- Cluster all robust signatures (from all

- Output and Downstream Analysis:

- Output the final list of reproducible signatures as a matrix of gene scores.