COG Database 2024: A Comprehensive Guide to Functional Categorization of Bacterial Genomes for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the COG (Clusters of Orthologous Genes) database, a pivotal resource for phylogenetic classification and functional annotation of prokaryotic proteins.

COG Database 2024: A Comprehensive Guide to Functional Categorization of Bacterial Genomes for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the COG (Clusters of Orthologous Genes) database, a pivotal resource for phylogenetic classification and functional annotation of prokaryotic proteins. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the 2024 database update covering 2,296 bacterial and archaeal genomes and 4,981 COGs. The scope spans from foundational concepts and evolutionary history to practical methodologies for genome annotation, troubleshooting common analysis challenges, and validation through comparative genomics and experimental case studies. This guide synthesizes current capabilities with emerging applications in microbial genomics, pathogenesis research, and therapeutic discovery.

Understanding COGs: Evolutionary Foundations and Database Architecture

Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs) represent a systematic approach to classifying proteins from complete genomes based on orthologous relationships, serving as a fundamental resource for functional annotation and evolutionary studies in microbiology and genomics. Originally developed in 1997 and maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the COG database provides a phylogenetic classification of proteins from sequenced genomes, enabling researchers to transfer functional information from characterized proteins to uncharacterized orthologs across species [1] [2] [3]. The core premise underlying the COG system is that orthologous proteins—direct evolutionary counterparts related by vertical descent from a common ancestor—typically retain the same fundamental function across different species, whereas paralogous proteins (related by gene duplication within a genome) often diverge functionally [2] [4] [3]. This conceptual framework makes COGs an invaluable tool for predicting protein functions in newly sequenced genomes and for conducting large-scale comparative genomic analyses.

The COG methodology has evolved significantly since its inception, with the most recent 2024 update expanding coverage to include 2,296 organisms (2,103 bacterial and 193 archaeal species) and 5,061 distinct COGs [1] [5]. A distinctive feature of the COG approach is its reliance on complete genome sequences, which enables more reliable identification of potential orthologs and paralogs compared to methods using incomplete genomic data [2]. The system utilizes flexible similarity cutoffs that accommodate proteins with dramatically different evolutionary rates, from barely detectable to extremely high sequence similarity, allowing COGs to reflect the natural evolutionary breadth of protein families without artificial constraints [2]. This flexibility is particularly valuable for classifying short proteins and distantly related orthologs that might be missed with strict BLAST cutoffs.

COG Construction and Classification Methodology

Core Construction Algorithm

The COG construction process employs a rigorous protocol that combines automated algorithms with manual curation to delineate orthologous groups. The methodology is built upon the fundamental concept that orthologs typically show reciprocal sequence similarity across genomes. The specific steps in COG construction include:

- Comprehensive sequence comparison: An all-against-all protein sequence comparison is performed using gapped BLAST, with low-complexity and predicted coiled-coil regions masked to improve accuracy [3].

- Paralog identification and grouping: Proteins from the same genome that are more similar to each other than to any proteins from other species are detected and collapsed into paralogous groups [3].

- Triangle of best hits detection: The system identifies triangles of mutually consistent genome-specific best hits (BeTs) across three phylogenetically distant genomes, applying the principle of transitivity in orthology relationships [2] [3].

- COG formation through triangle merging: Triangles with a common side are merged to form preliminary COGs, representing clusters of co-orthologous genes that accommodate one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many orthologous relationships [3].

- Manual curation and domain analysis: Each preliminary COG undergoes case-by-case analysis to eliminate false positives and identify multidomain proteins. Detected multidomain proteins are split into single-domain segments, which are then reassigned to appropriate COGs according to their distinct evolutionary affinities [3].

- Refinement of large COGs: Large COGs containing multiple members from all or several genomes are examined using phylogenetic trees, cluster analysis, and visual inspection of alignments, with some groups being split into smaller, more evolutionarily coherent COGs [3].

This construction method requires that a minimal COG includes proteins from at least three distinct phylogenetic lineages, ensuring robust evolutionary classification [3]. For adding new proteins to existing COGs, the COGNITOR program utilizes the same principle of consistency between genome-specific best hits, requiring that a new protein produces at least two best hits into the same COG to be considered a candidate member [4] [3].

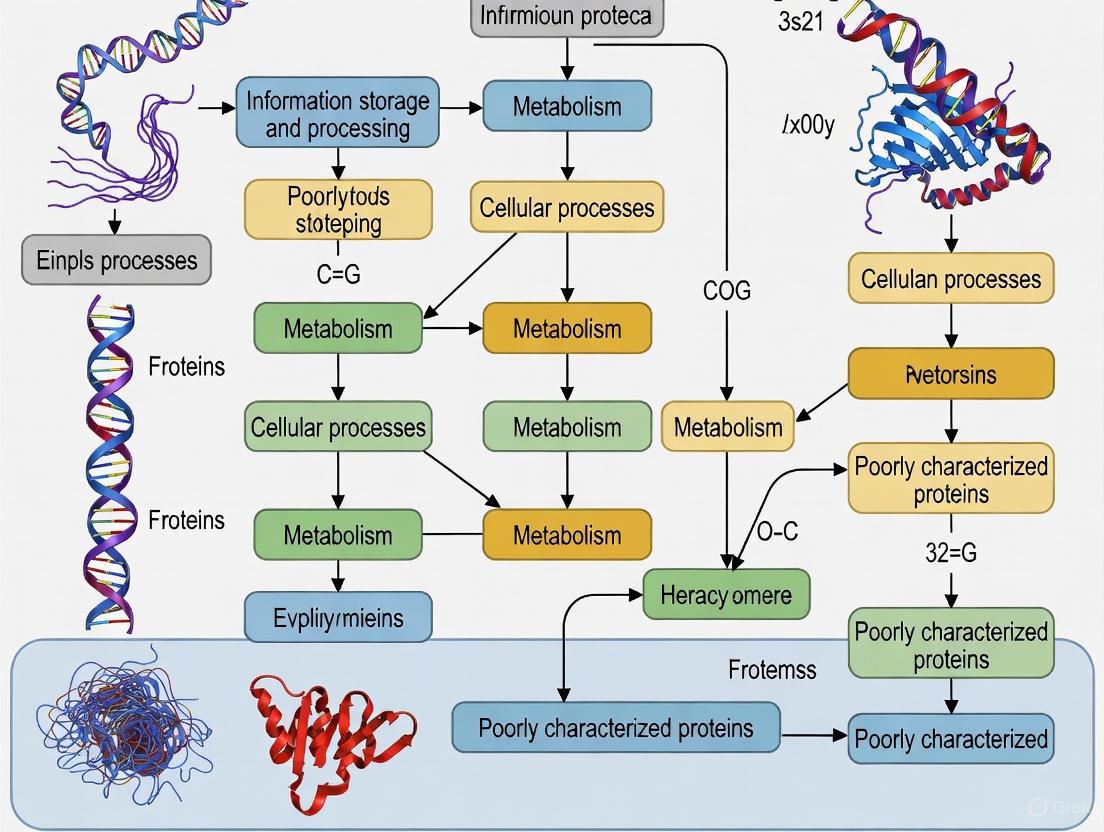

Visual Representation of COG Construction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic process of COG construction:

Table 1: COG Database Statistics (2024 Update)

| Parameter | Count | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Total COGs | 5,061 | Distinct clusters of orthologous genes |

| Organisms Covered | 2,296 | 2,103 bacterial and 193 archaeal species |

| Genomic Loci | 6,266,336 | Specific genomic positions represented |

| Protein IDs | 5,872,258 | Individual protein sequences classified |

| Taxonomic Categories | 42 | Distinct phylogenetic lineages represented |

| COG Symbols | 4,106 | Unique identifiers for protein families |

Source: NCBI COG Database Statistics [5]

Functional Annotation Using COGs

Annotation Workflow and Principles

COG functional annotation represents a powerful bioinformatics approach that leverages orthology and functional conservation to predict protein functions. The underlying principle is that genes sharing a common ancestor typically retain similar biological functions throughout evolution, with functional domains and key features being conserved [6]. The standard workflow for COG-based functional annotation involves four key stages:

- Data Preparation: Researchers collect query gene or protein sequences from the genome of interest and perform quality control to ensure sequence accuracy and integrity [6].

- Sequence Alignment and Homology Identification: Query sequences are compared against the COG database using alignment tools such as BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool). When a query sequence shows significant similarity to sequences within a specific COG group, it is considered homologous to that group [6] [2].

- Functional Assignment: Based on established homology, the query gene is assigned to a specific COG functional category. The COG system provides diverse functional categories covering various metabolic processes, cellular structures, and signaling pathways, enabling comprehensive functional classification [6].

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Annotation results undergo statistical analysis to assess the distribution of functional categories across the genome, with findings interpreted in the context of experimental data and biological knowledge [6].

A key advantage of the COG approach for functional annotation is its reliance on evolutionary classification rather than simple best-hit annotation, which reduces errors associated with transitive annotation and domain architecture differences that often plague conventional database searches [2]. The system's manual curation component further enhances annotation accuracy by verifying relationships and ensuring conservation of functionally important features across orthologs [3].

Visualization of Functional Annotation Process

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for COG-based functional annotation:

Applications in Microbial Genomics and Drug Development

Genome Annotation and Comparative Genomics

COG analysis serves as a cornerstone in functional genome annotation, particularly for newly sequenced microbial genomes. By mapping unknown genes to established COG categories, researchers can generate initial functional hypotheses for a significant proportion of coding sequences in a genome [6] [2]. In comparative genomics, COGs enable systematic comparison of functional capabilities across multiple species, revealing conservation and divergence of metabolic pathways and cellular processes [2]. The phyletic patterns of COGs—representing their presence or absence across different taxa—provide insights into evolutionary relationships, lineage-specific gene loss, and horizontal gene transfer events [2] [3]. This application is particularly valuable for understanding the genomic basis of phenotypic differences between related microorganisms and for identifying core genes essential across specific phylogenetic groups.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis and Drug Target Identification

The COG database facilitates metabolic pathway elucidation by identifying key enzymes and functional modules within complex metabolic networks [6]. For drug development professionals, this capability enables systematic mapping of metabolic vulnerabilities in pathogenic microorganisms. Category Q (Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism) exemplifies this application, containing COGs related to specialized metabolic pathways that often produce bioactive compounds with antimicrobial properties [7]. The identification of pathogen-specific COGs—those present in pathogenic strains but absent in non-pathogenic relatives or host organisms—provides promising targets for novel antimicrobial development. Additionally, COG-based essential gene prediction through phylogenetic profiling helps prioritize targets for drug discovery by identifying genes conserved across pathogens but absent in humans, potentially reducing host toxicity concerns.

Protocol: COG-Based Functional Annotation of Bacterial Genomes

Purpose: To annotate protein-coding genes from a newly sequenced bacterial genome using the COG database.

Materials and Bioinformatics Tools:

- High-quality assembled bacterial genome sequence

- Protein-coding gene predictions in FASTA format

- NCBI COG database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/) [5]

- BLAST+ software suite (version 2.0 or higher)

- Computing infrastructure with adequate memory and storage

Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Extract predicted protein sequences from the target genome.

- Format sequences in FASTA format and perform quality control to remove fragments and sequences with ambiguous residues.

Database Setup:

- Download the latest COG database from NCBI, including COG sequence files and associated metadata.

- Format the database for BLAST search using

makeblastdbcommand.

Sequence Comparison:

- Perform BLASTP search of query proteins against the COG database with an E-value threshold of 1e-5:

blastp -query your_sequences.fasta -db cog_db -out blast_results.xml -outfmt 5 -evalue 1e-5 -num_threads 8

- Perform BLASTP search of query proteins against the COG database with an E-value threshold of 1e-5:

COG Assignment:

- Parse BLAST results to identify significant hits (E-value < 1e-5, identity > 30%, coverage > 70%).

- Apply the COGNITOR principle: assign query proteins to COGs when they show at least two best hits to the same COG group.

- For proteins with hits to multiple COGs, examine domain architecture and perform manual curation to resolve ambiguities.

Functional Transfer:

- Transfer functional annotations from the best-matched orthologs in the COG database.

- Assign corresponding functional category codes (e.g., Q for Secondary metabolites) based on COG classification.

Validation and Quality Control:

- Verify conserved domain architectures using CDD or InterProScan.

- Cross-check annotations with other databases (UniProt, KEGG) for consistency.

- Manually review annotations for multidomain proteins and complex cases.

Troubleshooting:

- For low annotation rates, consider relaxing BLAST thresholds or using profile-based methods (RPS-BLAST) against COG position-specific scoring matrices [2].

- For ambiguous assignments, examine phylogenetic context and genomic neighborhood for additional evidence.

Research Reagent Solutions for COG-Based Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for COG Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Database | Function in COG Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Core Databases | NCBI COG Database [1] [5] | Primary resource for COG classifications, functional categories, and precomputed orthologous groups |

| RefSeq Complete Genomes [5] | Curated genome sequences essential for accurate orthology assignment and new COG construction | |

| Analysis Software | BLAST+ Suite [2] | Standard tool for sequence comparison and identification of homologous relationships |

| COGNITOR Program [4] [3] | Specialized tool for fitting new protein sequences into existing COG classifications | |

| Complementary Resources | EggNOG Database [2] | Extended orthology database with automated assignments for larger genome sets |

| CDD/InterPro [2] | Domain databases for verifying domain architecture conservation in orthologs | |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-performance Computing Cluster | Essential for all-against-all genome comparisons and large-scale phylogenetic analyses |

Advancements and Future Perspectives

The COG database has undergone significant evolution since its initial development, with the 2024 update incorporating numerous enhancements including expanded coverage of microbial diversity, improved annotations with references, and integration with PDB structures [1]. Recent developments have focused on increasing the coverage of proteins involved in specialized processes such as protein secretion pathways and expanding the repertoire of COGs for proteins with previously unknown functions [1] [5]. Future directions for COG research include addressing current limitations related to species coverage, particularly for understudied microbial lineages, and improving the annotation of fast-evolving or lineage-specific genes that remain challenging to classify [6] [2]. The integration of COG analysis with other 'omics' data types, including transcriptomics and proteomics, presents promising opportunities for systems-level understanding of microbial cellular processes. For drug development applications, ongoing efforts to enhance the resolution of COG classifications for target families such as transporters, receptors, and enzymes will further strengthen their utility in identifying and validating novel antimicrobial targets. As microbial genomics continues to expand with thousands of new genome sequences, the COG framework provides an essential foundation for organizing this wealth of information and extracting biologically meaningful insights for basic research and applied biotechnology.

The Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) database represents a cornerstone in the field of computational genomics, providing an essential framework for the functional and evolutionary classification of genes across microbial genomes. Originally created in 1997, the COG database has continuously evolved to accommodate the explosion of genomic data while refining its methodologies and expanding its scope [8] [3]. This framework has become indispensable for functional annotation of newly sequenced genomes, phylogenetic analysis, and identification of novel drug targets in pathogenic bacteria [3] [9]. The historical progression of COG reflects broader trends in microbial genomics, from the initial analysis of a handful of genomes to the current era of big data, where thousands of bacterial and archaeal genomes require systematic categorization [8] [10]. This article traces the COG database's development from its inception to its most recent 2024 update, focusing on its growing applications in functional categorization of bacterial genomes and its critical role in modern genomic research and drug discovery.

Historical Timeline and Quantitative Evolution

The COG database has undergone significant quantitative and qualitative changes since its establishment, marked by major updates that expanded both genomic coverage and functional annotations. The following table summarizes the key milestones in its evolution:

Table 1: Historical Evolution of the COG Database

| Year | Number of Genomes | Number of COGs | Key Developments and Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 7 genomes (5 bacteria, 1 archaea, 1 eukaryote) | 720 COGs | Initial development based on bidirectional best hits; focus on orthology detection [3] |

| 2000 | 21 complete genomes | 2,091 COGs | Introduction of COGNITOR program; expanded to include 56-83% of prokaryotic gene products [3] |

| 2003 | 66 unicellular organisms | 4,873 COGs | Major expansion including eukaryotes (KOGs); introduction of phyletic pattern search tool [10] [4] |

| 2014 | 753 genomes (630 bacteria, 123 archaea) | 4,872 COGs | Genus-level coverage; refined annotations; improved coverage of poorly characterized families [9] |

| 2021 | 1,309 species (1,187 bacteria, 122 archaea) | 4,877 COGs | Addition of CRISPR-Cas, sporulation, and photosynthesis COGs; pathway-based groupings [9] |

| 2024 | 2,296 species (2,103 bacteria, 193 archaea) | 4,981 COGs | Inclusion of bacterial secretion systems; updated taxonomy; enhanced RNA modification annotations [8] |

The most recent 2024 update represents the most significant expansion in recent years, with a 75% increase in genome coverage compared to the 2021 version [8]. This expansion strategically focuses on comprehensive genus-level representation, selecting a single representative genome per genus with exceptions for model organisms and important pathogens. The update also incorporated 64 genomes listed at the 'chromosome' level to improve coverage of poorly sampled lineages [8]. The distribution of COGs across genomes follows a characteristic pattern, with a small fraction of nearly universal COGs present in almost all genomes and the majority found in only a few genomes, reflecting the diverse evolutionary paths of prokaryotic lineages [8].

Methodological Evolution: From Basic Clustering to Advanced Annotation

Core COG Construction Methodology

The fundamental methodology for COG construction has remained consistent since its inception, based on the principle of identifying orthologous relationships through sequence similarity and evolutionary relationships. The original procedure involved several key steps that have been refined over time:

Comprehensive Sequence Comparison: Performing all-against-all protein sequence comparisons using gapped BLAST after masking low-complexity and predicted coiled-coil regions [3]

Paralog Detection and Grouping: Identifying and collapsing obvious paralogs within the same genome that are more similar to each other than to any proteins from other species [3]

Orthology Triangle Detection: Detecting triangles of mutually consistent, genome-specific best hits (BeTs) considering the paralogous groups identified in the previous step [3]

COG Formation: Merging triangles with a common side to form preliminary COGs [3]

Manual Curation and Validation: Case-by-case analysis of each COG to eliminate false positives and identify multidomain proteins, which are split into single-domain segments [3]

Refinement of Large COGs: Examination of large COGs containing multiple members using phylogenetic trees, cluster analysis, and visual inspection of alignments, with subsequent splitting into smaller, more accurate groups [3]

The COGNITOR program, introduced early in the database's development, remains crucial for adding new members to existing COGs based on the principle of consistency between genome-specific best hits [3] [10]. The current threshold for assigning proteins to COGs requires three best hits to minimize false assignments, with users having the option to increase stringency by requiring more hits [3].

Evolution of Taxonomic and Functional Annotation

The 2024 update introduced significant improvements in taxonomic classification and functional annotation. Taxonomically, the database adopted the new bacterial and archaeal phylum names mandated by the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes, which added the suffix '-ota' to previously used names (e.g., Firmicutes became Bacillota) [8]. This update also improved coverage of previously underrepresented archaeal phyla such as Asgardarchaeota and bacterial phyla including Campylobacterota and Myxococcota [8].

Functionally, the 2024 release added approximately 100 new COGs, primarily focused on bacterial protein secretion systems, including types II through X, as well as Flp/Tad and type IV pili [8]. These additions enable straightforward identification of prokaryotic lineages that possess or lack particular secretion systems, with significant implications for understanding pathogenesis and developing antimicrobial strategies. The annotation improvements extended to rRNA and tRNA modification enzymes, multi-domain signal transduction proteins, and previously uncharacterized protein families [8]. The database now includes updated annotations for over 150 COGs, with 43 previously uncharacterized COGs (S-COGs) assigned to specific functional groups and 13 more assigned to the poorly characterized group (R-COGs) [8].

Table 2: Selected COGs with Updated Annotations in the 2024 Release

| COG Number | Previous Annotation | Updated Annotation | Functional Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| COG1649 | Uncharacterized lipoprotein YddW, UPF0748 family | Divisome-localized peptidoglycan glycosyl hydrolase DigH/YddW | Cell wall biogenesis |

| COG2324 | Uncharacterized membrane protein | Carotenoid 2′,3′-hydratase CruF | Metabolic processes |

| COG4683 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | Toxin component of RelE/ParE type II toxin-antitoxin system | Defense mechanisms |

| COG4924 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | Nuclease subunit JetD of Wadjet anti-plasmid defense system | Defense mechanisms |

| COG5352 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | Transcription factor GcrA interacting with sigma70 | Transcription |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Functional Annotation of Novel Bacterial Genomes Using COGs

Purpose: To assign putative functions to genes from newly sequenced bacterial genomes through orthology-based analysis using the COG database.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality annotated protein sequences from the target genome

- Access to the COG database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/COG/)

- Computational tools: BLAST+ suite, COGNITOR program

- Workstation with minimum 8GB RAM and multi-core processor for genomes >5,000 genes

Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Obtain complete protein sequence file in FASTA format

- Ensure sequences are properly annotated with unique identifiers

- For large genomes (>5,000 genes), pre-filter sequences to remove obvious transposases and phage-related proteins

Sequence Comparison:

- Run BLASTP search against the COG database using an E-value cutoff of 0.001

- Use the following command-line parameters for optimal sensitivity:

-evalue 0.001 -max_target_seqs 50 -outfmt 6 - For divergent genomes (e.g., obligate parasites), consider using PSI-BLAST with 3 iterations

COG Assignment:

- Process BLAST results using the COGNITOR program with default parameters

- Apply the three-best-hit criterion for robust COG assignment

- Manually verify assignments for essential genes (e.g., ribosomal proteins, RNA polymerase subunits)

Functional Transfer:

- Assign putative functions based on experimentally characterized members of the COG

- Note any inconsistencies in domain architecture that might indicate erroneous assignment

- Flag multidomain proteins for additional analysis using CDD or InterProScan

Phyletic Pattern Analysis:

- Identify lineage-specific gene losses by comparing COG distribution across related taxa

- Use absence of universal single-copy COGs to assess genome completeness

- Identify potential horizontal gene transfer events through anomalous phyletic patterns

Troubleshooting:

- For low assignment rates (<60% of genes), try iterative searches with profile-based methods

- For ambiguous assignments in large paralogous families, construct phylogenetic trees for resolution

- Always verify essential metabolic pathways through pathway reconstruction tools like KEGG

Protocol for Identification of Novel Drug Targets in Bacterial Pathogens

Purpose: To utilize COG functional categorization and phyletic patterns to identify potential species-specific drug targets in pathogenic bacteria.

Materials and Reagents:

- COG database with phyletic pattern search capability

- Genomic data for target pathogen and related non-pathogenic species

- Essential gene data from model organisms (e.g., E. coli, B. subtilis)

- Host genome data (human or other relevant host)

Procedure:

Target Selection Criteria Definition:

- Define parameters for ideal drug target: essential for pathogen viability, absent in host, conserved across pathogen strains

- Establish similarity thresholds to exclude proteins with significant similarity to host proteins (E-value < 10^-10)

Comparative Genomic Analysis:

- Identify COGs present in the target pathogen but absent in the host using phyletic pattern search

- Further refine to COGs present in all clinical isolates of the pathogen but absent in commensal relatives

- Cross-reference with essential gene data from model bacteria

Functional Prioritization:

- Prioritize COGs involved in essential processes: cell wall biosynthesis, DNA replication, protein synthesis

- Favor enzymes over structural proteins for small molecule targeting

- Avoid proteins with extensive paralogs due to potential functional redundancy

Experimental Validation Design:

- Design essentiality tests using gene knockout or knockdown methods

- Plan structural studies for promising targets without existing structures

- Develop activity assays based on known functions of COG members

Validation:

- Confirm essentiality through genetic experiments

- Verify expression during infection conditions

- Assess conservation across diverse clinical isolates

- Determine structural feasibility for drug binding

Visualization of COG Workflows and Functional Relationships

COG Construction and Analysis Workflow

Diagram 1: COG Construction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the key steps in constructing Clusters of Orthologous Genes, from initial sequence analysis through manual curation and final annotation.

COG-Based Functional Categorization System

Diagram 2: COG Functional Categorization and Applications. This diagram shows the major functional categories within the COG system and their primary research applications, highlighting the relationship between classification and practical use cases.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for COG-Based Analyses

| Resource | Type | Function and Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| COG Database | Database | Core resource containing clusters of orthologous genes with functional annotations | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/COG/ [8] |

| COGNITOR | Software Program | Automated tool for fitting new protein sequences into existing COGs | Available through COG website [3] |

| BLAST+ Suite | Software Toolkit | Sequence similarity search tool essential for identifying orthologous relationships | https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [3] |

| NCBI RefSeq | Database | Comprehensive, non-redundant sequence database used for COG genome selection | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/ [8] |

| Phyletic Pattern Search | Analysis Tool | Identifies COGs with specific presence/absence patterns across taxa | Integrated in COG web interface [10] |

| CDD Database | Database | Conserved Domain Database used for annotation verification and domain analysis | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/ [8] |

| Archaeal COGs (arCOGs) | Specialized Database | Archaea-specific orthologous groups for improved annotation of archaeal genomes | https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/COG/ [9] |

The COG database has evolved from a specialized tool for analyzing a handful of genomes to an indispensable resource for the functional annotation and evolutionary analysis of thousands of microbial genomes. The historical trajectory from 1997 to 2024 demonstrates consistent expansion in scope and refinement in methodology, with the most recent update substantially improving coverage of bacterial diversity and annotation of secretion systems and RNA modification enzymes [8]. For researchers focused on bacterial pathogenesis and drug development, the COG framework provides a powerful approach for identifying potential therapeutic targets through comparative genomics and phyletic pattern analysis. The continued development of specialized COG collections for particular taxonomic groups and the ongoing refinement of functional annotations ensure that this resource will remain relevant as microbial genomics enters an era of increasingly complex and diverse datasets. Future directions likely include further expansion of archaeal COGs, splitting of paralog-rich COGs into finer-grained orthologous groups, and integration with other functional databases to provide increasingly accurate functional predictions for the rapidly growing universe of microbial genomic data.

The Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) database represents a foundational resource for the comparative genomic analysis of prokaryotes, providing a phylogenetic classification of proteins based on the concept of orthology. Originally created in 1997, the COG database has undergone multiple revisions to incorporate the expanding collection of sequenced genomes and refine its functional annotations [11] [3]. For researchers investigating bacterial physiology, evolution, and potential drug targets, the COG system offers a critical framework for transferring functional information from characterized proteins to novel gene products through identified orthologous relationships [3]. The 2024 update marks a significant expansion in genomic coverage and functional pathways, solidifying its utility in modern microbial genomics [11]. This application note details the updated scope, statistical coverage, and practical methodologies for employing the COG database in the functional categorization of bacterial genomes.

The 2024 update of the COG database substantially increases its genomic coverage from 1,309 to 2,296 prokaryotic species, encompassing 2,103 bacterial and 193 archaeal genomes [11] [5]. This collection strategically includes, in most cases, a single representative genome per genus, thereby maximizing phylogenetic diversity. The selected genomes cover all genera of bacteria and archaea listed with 'complete genomes' in NCBI databases as of November 2023 [11]. The protein family inventory has been expanded from 4,877 to 4,981 COGs, with a primary focus on incorporating families involved in bacterial protein secretion systems [11]. Consequently, the database now includes comprehensive pathways and functional groups for secretion systems of types II through X, as well as Flp/Tad and type IV pili [11]. These additions enable researchers to readily identify and examine prokaryotic lineages that possess or lack specific secretion machinery, a feature relevant for understanding pathogenesis and host-microbe interactions in drug development.

Key Statistics and Functional Categories

Table 1: COG Database Scope and Statistics (2024 Update)

| Metric | Detail | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Total Genomes | 2,296 | [11] [5] |

| Bacterial Genomes | 2,103 | [11] |

| Archaeal Genomes | 193 | [11] |

| Total COGs | 4,981 | [11] |

| Genomic Loci | 6,266,336 | [5] |

| Protein IDs | 5,872,258 | [5] |

Table 2: Representative COG Functional Categories and Additions in the 2024 Update

| Functional Category/Group | Description and Relevance | Update Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Secretion Systems | Pathways for types II through X, Flp/Tad, and type IV pili. | Newly added functional groupings; crucial for understanding virulence and host interaction. [11] |

| RNA Modification Proteins | Proteins involved in rRNA and tRNA modification. | Improved annotations for better functional prediction. [11] |

| Signal Transduction | Multi-domain proteins involved in environmental sensing and response. | Enhanced annotation detail. [11] |

| Previously Uncharacterized Families | Protein families with previously unknown function. | New annotations for select families. [11] |

Experimental Protocols for COG-Based Functional Annotation

Leveraging the COG database for functional annotation involves a series of defined steps, from data preparation to functional interpretation. The following protocol describes a standard workflow for annotating a set of protein sequences, such as those derived from a newly sequenced prokaryotic genome.

Protocol: Functional Annotation of Protein Sequences Using the COG Database

1. Dataset Preparation: Begin with a set of protein sequences, typically predicted from a genome assembly. The dataset should be in FASTA format, with each entry containing a unique identifier [12].

2. COG Assignment via Sequence Similarity Search:

- Tool Selection: For large-scale datasets, the software DIAMOND is highly recommended. DIAMOND is a BLAST-compatible tool that can perform alignments up to 20,000 times faster than BLAST while maintaining consistent results, making it ideal for annotating thousands of genes efficiently [12].

- Execution Command:

This command specifies a sensitive alignment mode (

--more-sensitive), an E-value cutoff of 1e-5, and requests up to 20 target sequences per query [12]. - Alternative Approach: Some integrated annotation pipelines, such as anvi'o, provide dedicated workflows via the

anvi-run-ncbi-cogsprogram, which handles the setup and execution of the search against a local COG database [13].

3. Annotation Transfer: The alignment results are parsed to assign COG identifiers to the query proteins. This is typically achieved by identifying the best hits to proteins within the COG database that meet predefined score and E-value thresholds. The COGNITOR program, which is based on the principle of consistency of genome-specific best hits, is the historical method for this step [3]. A protein is assigned to a COG if it yields a sufficient number of best hits (BeTs) into that same COG, a method that helps minimize false assignments [3].

4. Functional and Categorical Interpretation: Once COG assignments are made, the corresponding functional annotations and categorical classifications (e.g., 'Amino acid transport and metabolism') are transferred to the query proteins from the COG database. This data can then be used for downstream statistical analyses, such as determining the distribution of genes across various functional categories.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this annotation process:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for COG Annotation

| Item/Resource | Function and Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| COG Database | A curated resource of Clusters of Orthologous Genes used as a reference for functional annotation. | The 2024 version is available from the NCBI website and FTP site. [11] [5] |

| DIAMOND Software | An ultra-fast, BLAST-compatible sequence aligner for matching protein sequences against the COG database. | Essential for efficient annotation of large metagenomic or genomic datasets. [12] |

| BLAST Suite | The standard suite of programs (e.g., blastp) for sequence similarity searching. | A well-established alternative to DIAMOND for smaller datasets. [3] |

| anvi'o Platform | An integrated analysis and visualization platform for omics data. | Provides the anvi-run-ncbi-cogs program for a streamlined COG annotation workflow. [13] |

| BASys2 | A next-generation bacterial genome annotation system. | One of many comprehensive pipelines that can utilize COG data among other resources for in-depth annotation. [14] |

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The 2024 update of the COG database, with its systematic coverage of 2,296 prokaryotic genomes, provides an indispensable tool for functional genomics. Its expansion to include key systems like specialized secretion pathways directly supports research into microbial mechanisms relevant to drug discovery, such as virulence and resistance [11]. The consistent, orthology-based framework of COGs allows for reliable transfer of functional annotations and enables robust comparative analyses across diverse taxonomic lineages [3].

When performing COG functional annotation analysis, it is critical to move beyond simply reporting the most abundant categories. A high-quality analysis should identify key biological functions critical to the organism's biology, compare the COG distribution with other species to discuss evolutionary and functional similarities or differences, and acknowledge methodological limitations [15]. These limitations include the database's inherent scope, which, despite the update, does not cover all prokaryotic diversity, and the fact that not all proteins in a genome will find a match in the COG database, leaving a portion of any genome unannotated by this system [15] [3].

In conclusion, the COG database remains a cornerstone for the functional categorization of bacterial and archaeal genomes. Its continued curation and expansion ensure it will remain a vital resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to decipher the functional potential encoded in prokaryotic DNA.

The Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) database represents a foundational framework for the phylogenetic classification of proteins from completely sequenced genomes. Established in 1997 and maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the COG system provides a robust platform for functional annotation and evolutionary studies of bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic genes [5] [9]. The core principle underlying the COG database is the identification of orthologous relationships—genes in different species that evolved from a common ancestral gene through vertical descent, which typically retain the same function over evolutionary time [3]. This orthology-based approach enables reliable transfer of functional information from experimentally characterized proteins in model organisms to uncharacterized proteins in newly sequenced genomes, making it an indispensable tool for genomic annotation and comparative analysis.

The functional classification system within COG organizes proteins into hierarchically structured categories that reflect their cellular roles and participation in biological pathways. This systematic categorization allows researchers to quickly assess the functional capabilities of an organism, identify missing metabolic components, and predict the biological pathways operating within a given genome. The most recent 2024 update of the COG database has substantially expanded its coverage to include 2,296 species (2,103 bacteria and 193 archaea), organized into 4,981 COGs that are further classified into functional pathways and systems [8]. This comprehensive coverage, typically with a single representative genome per genus, provides researchers with an unparalleled resource for exploring functional genomics across microbial diversity.

The 17 Broad Functional Categories

The COG database classifies proteins into 17 broad functional categories that encompass the major cellular functions and systems found across bacterial and archaeal lineages [16] [3]. This classification system enables researchers to quickly assess the functional composition of genomes and perform comparative analyses across taxonomic groups. The categories range from core informational processing functions to metabolic, cellular processing, and poorly characterized activities, providing a holistic view of an organism's functional capabilities.

Table 1: The 17 Broad Functional Categories in the COG Database

| Category Code | Functional Category | Representative Functions | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | Translation | Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, ribosomal proteins, translation factors | Includes core components of the translation machinery |

| K | Transcription | RNA polymerase subunits, transcription factors | DNA-dependent transcription regulation |

| L | Replication, recombination and repair | DNA polymerase, helicases, nucleases | DNA replication, repair, and recombination systems |

| O | Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | Proteases, chaperones, protein modification enzymes | Protein folding, degradation, and modification |

| M | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | Peptidoglycan synthesis, outer membrane proteins | Cell envelope structure and function |

| N | Cell motility and secretion | Flagellar proteins, secretion system components | Bacterial movement and protein secretion |

| T | Signal transduction mechanisms | Two-component systems, serine/threonine kinases | Cellular signaling and response pathways |

| U | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport | Sec secretion system, vesicle transport | Protein transport across membranes |

| V | Defense mechanisms | Restriction-modification systems, toxin-antitoxin systems | Defense against phages and other threats |

| C | Energy production and conversion | ATP synthase, oxidoreductases, photosynthetic complexes | Energy metabolism and conversion |

| G | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | Glycolytic enzymes, sugar transporters | Carbohydrate utilization and metabolism |

| E | Amino acid transport and metabolism | Amino acid biosynthesis enzymes, transporters | Amino acid metabolism and transport |

| F | Nucleotide transport and metabolism | Purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis enzymes | Nucleotide metabolism |

| H | Coenzyme transport and metabolism | Vitamin and cofactor biosynthesis enzymes | Coenzyme and vitamin metabolism |

| I | Lipid transport and metabolism | Fatty acid biosynthesis, phospholipid metabolism | Lipid metabolism |

| P | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | Ion channels, transporters, metalloenzymes | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | Antibiotic biosynthesis, polyketide synthases | Secondary metabolite production |

| R | General function prediction only | Conserved proteins with predicted but unconfirmed function | Predicted biochemical activity without specific functional assignment |

| S | Function unknown | Poorly conserved or uncharacterized proteins | No predictable function assigned |

The distribution of proteins across these categories reveals fundamental insights into microbial biology. Informational categories (J, K, L) dealing with transcription, translation, and replication tend to be highly conserved across phylogenetically diverse organisms and are often used to reconstruct deep evolutionary relationships [3]. In contrast, metabolic categories (C, E, F, G, H, I, P) frequently show patchier phylogenetic patterns reflecting adaptations to specific ecological niches and nutritional requirements [3]. The categories for cellular processes and signaling (M, N, O, T, U, V) often contain lineage-specific expansions that correlate with particular lifestyles or environmental adaptations.

A notable feature of the classification system is the explicit acknowledgment of limited functional knowledge through the R (General function prediction only) and S (Function unknown) categories [3] [8]. The persistence of these categories, even in the most recent database updates, highlights the significant gaps that remain in our understanding of microbial gene functions despite decades of genomic research. The 2024 COG update specifically addressed this knowledge gap by reclassifying 43 former S-COGs into specific functional categories and assigning 13 more to the R group based on recent experimental evidence and improved bioinformatic analyses [8].

COG Pathways and Functional Systems

Beyond the 17 broad categories, the COG database organizes related protein families into specific pathways and functional systems that represent coordinated biological processes [8] [17]. This pathway-level organization enables researchers to rapidly identify all components of a particular cellular system within a genome and assess its functional completeness. The pathway classification has been significantly expanded in recent updates, particularly for bacterial secretion systems and RNA modification enzymes, reflecting advances in our understanding of these complex cellular machines.

Table 2: Selected COG Pathways and Functional Systems

| Pathway/Functional System | Number of COGs | Biological Role | Taxonomic Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas system | 46 | Adaptive immune system against mobile genetic elements | Widespread but patchy in bacteria and archaea |

| Sec pathway | 9 | General secretory pathway for protein translocation | Universal in bacteria and archaea |

| Type II secretion/Type IV pili | 27 | Protein secretion and pilus assembly | Mainly Gram-negative bacteria |

| Type VI secretion system | 25 | Contact-dependent toxin delivery into target cells | Predominantly Gram-negative bacteria |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases | 26 | Attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs | Universal |

| Ribosome 30S subunit | 21 | Small ribosomal subunit proteins | Universal |

| Ribosome 50S subunit | 33 | Large ribosomal subunit proteins | Universal |

| RNA polymerase | 16 | DNA-dependent RNA transcription | Universal |

| FoF1-type ATP synthase | 12 | ATP synthesis coupled to proton gradient | Widespread |

| NADH dehydrogenase | 15 | Electron transport chain complex I | Widespread |

| Glycolysis | 18 | Glucose breakdown to pyruvate | Universal central pathway |

| TCA cycle | 16 | Aerobic respiration and carbon skeleton provision | Widespread in aerobic organisms |

| Purine biosynthesis | 20 | De novo purine nucleotide synthesis | Universal |

| Arginine biosynthesis | 12 | Arginine synthesis from glutamate | Variable, pathway completeness indicates metabolic capabilities |

| tRNA modification | 67 | Chemical modification of tRNA nucleotides | Universal, with variations |

| 16S rRNA modification | 16 | Ribosomal RNA modification | Universal |

| 23S rRNA modification | 12 | Ribosomal RNA modification | Universal |

| Photosystem II | 26 | Light-driven water oxidation in photosynthesis | Cyanobacteria and photosynthetic bacteria |

The pathway classification reveals several important biological insights. First, core informational pathways such as ribosome components, RNA polymerase, and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases show remarkable conservation across the tree of life, with nearly universal distribution among bacterial and archaeal lineages [3]. Second, metabolic pathways display considerable variation that often correlates with an organism's habitat and ecological niche [17]. Third, specific adaptive systems such as secretion systems and CRISPR-Cas arrays show patchy distributions that likely reflect horizontal gene transfer events and specific evolutionary pressures [8].

The 2024 COG update placed special emphasis on bacterial secretion systems, adding over 100 new COGs primarily dedicated to these complex molecular machines [8]. The database now includes comprehensive coverage of secretion systems types II through X, as well as Flp/Tad and type IV pili. This expansion enables researchers to systematically examine the distribution of these systems across prokaryotic lineages and investigate their evolutionary relationships. Similarly, significant improvements were made to the annotation of tRNA and rRNA modification enzymes, with updated functional descriptions that reflect recent discoveries about their diverse roles in fine-tuning translation and regulating gene expression [8].

Experimental Protocols for COG Analysis

Protocol 1: Genome Annotation Using COGNITOR

The COGNITOR program is the primary tool for assigning proteins from newly sequenced genomes to existing COGs, enabling rapid functional annotation based on orthology [3]. The program operates on the principle of consistency of genome-specific best hits, requiring that a protein from a new genome shows significant similarity to multiple members of a particular COG.

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein sequences from the target genome in FASTA format

- COG database (current version available from NCBI FTP site)

- BLAST+ software suite for sequence comparison

- Computational resources capable of handling whole-genome analysis

Procedure:

- Retrieve the current COG database from the NCBI FTP site (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/COG/) [8]. The database includes protein sequences for all COG members, COG definitions, and functional annotations.

Perform all-against-all sequence comparison between the target proteome and the COG database using the gapped BLAST program. Mask low-complexity and predicted coiled-coil regions to avoid spurious matches [3].

Identify best hits from the target proteome to each genome in the COG database. The COGNITOR algorithm requires that a protein from the target genome shows significant similarity (E-value below a specified threshold, typically 0.001) to multiple proteins within the same COG.

Apply the consistency criterion: A protein is assigned to a COG if it produces at least three consistent best hits to members of that COG from different species [3]. This multi-genome requirement reduces false positive assignments.

Validate domain architecture: For proteins assigned to COGs, verify that the domain architecture is consistent with other COG members. Multidomain proteins may need to be split into individual domains, with each domain assigned to separate COGs [3].

Manual curation: Examine borderline cases manually by reviewing alignment quality, conservation of functional residues, and domain structure. This step is particularly important for COGs containing paralogs with distinct functions.

Troubleshooting:

- If a protein produces best hits to multiple COGs, it may represent a multidomain protein that needs to be split into individual domains.

- Proteins with weak similarity to a COG (E-value > 0.001) but meeting the best-hit criteria should be flagged for manual inspection.

- Proteins that cannot be assigned to any existing COG may represent novel protein families not yet captured in the database.

Protocol 2: Phylogenetic Pattern Analysis for Comparative Genomics

Phylogenetic patterns—the pattern of species presence or absence in each COG—provide powerful insights into gene gain and loss events, horizontal gene transfer, and lineage-specific adaptations [3]. Analyzing these patterns across multiple genomes can reveal core genes essential across taxa and accessory genes associated with specific phenotypes.

Materials and Reagents:

- COG database with phylogenetic pattern data

- Genome metadata (taxonomy, habitat, phenotype information)

- Statistical analysis software (R, Python with pandas)

- Visualization tools for displaying pattern distributions

Procedure:

- Extract phylogenetic patterns for COGs of interest from the database. Each pattern is represented as a binary string indicating presence (1) or absence (0) in each reference genome.

Identify core and accessory COGs: Calculate the fraction of genomes represented in each COG. COGs found in ≥90% of genomes are typically considered "core" genes, while those with patchier distributions represent "accessory" genes [8].

Correlate patterns with phenotypes: For COGs with patchy distributions, examine whether presence/absence correlates with specific biological characteristics (e.g., pathogenicity, metabolic capabilities, environmental adaptations). Statistical tests such as Fisher's exact test can identify significant associations.

Reconstruct gene gain and loss events: Using phylogenetic trees of the organisms, map COG presence/absence onto branches to infer evolutionary events. Tools like COUNT or GLOOME can automate this process.

Identify horizontally transferred genes: Look for COGs with distributions that conflict with the species phylogeny, particularly those restricted to a specific habitat rather than a taxonomic group.

Functional enrichment analysis: For sets of COGs with similar phylogenetic patterns, perform functional enrichment analysis to identify biological processes over-represented in the set.

Implementation Example: A study investigating acidophilic bacteria might identify COGs present in acidophiles but absent in neutralophiles. These COGs might include proton export systems, specialized membrane transporters, or DNA repair mechanisms adapted to acidic conditions. The phylogenetic pattern would reveal whether these adaptations were acquired vertically from a common acidophilic ancestor or horizontally transferred between diverse acidophiles.

Protocol 3: Pathway Completion Analysis

Pathway completion analysis assesses whether all components of a biological pathway are present in a genome, providing insights into an organism's metabolic capabilities and potential auxotrophies [17]. This approach is particularly valuable for predicting growth requirements and metabolic dependencies.

Materials and Reagents:

- Annotated genome with COG assignments

- COG pathway collections (available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/pathways/)

- Reference pathway databases (KEGG, MetaCyc) for comparison

- Specialized software for pathway visualization and analysis

Procedure:

- Select pathways for analysis based on biological questions. For example, amino acid biosynthesis pathways for investigating auxotrophies, or secretion systems for studying host-pathogen interactions.

Retrieve COG members for each component of the pathway from the COG pathway database. For example, the arginine biosynthesis pathway includes 12 COGs representing different enzymatic steps [17].

Map COG assignments from the target genome onto the pathway components. Identify which pathway components are present and which are missing.

Assess pathway completeness: Determine whether the pathway appears complete, partially complete, or absent. Consider alternative enzymes or non-orthologous replacements that might fulfill the same function.

Evaluate functional implications: For incomplete pathways, predict metabolic capabilities or auxotrophies. For example, missing components in an amino acid biosynthesis pathway suggest that the organism requires that amino acid in its growth medium.

Compare across taxa: Analyze pathway conservation across related organisms to distinguish lineage-specific losses from general absences in larger taxonomic groups.

Case Study: Amino Acid Biosynthesis Analysis of the aromatic amino acid biosynthesis pathway (23 COGs) across bacterial genomes reveals distinct patterns of pathway completeness. While free-living organisms typically maintain complete pathways, intracellular pathogens and symbionts often show extensive pathway erosion, reflecting their reliance on host-derived nutrients [17]. This pattern is particularly evident in organisms with extremely reduced genomes such as Mycoplasma genitalium, which lacks multiple amino acid biosynthesis pathways [3].

Visualization of COG Classification and Analysis Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate key classification relationships and analytical workflows within the COG database system, providing visual guides to the organization and application of this functional classification framework.

Diagram 1: COG Database Construction and Classification Hierarchy. This workflow illustrates the process from genome collection through orthology detection to functional classification.

Diagram 2: COG-Based Analysis Workflow for New Genomes. This chart outlines the primary applications of the COG system for functional annotation and comparative genomics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for COG Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Resource | Function/Purpose | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database | COG Database | Central repository of Clusters of Orthologous Genes | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/COG [5] |

| Software Tool | COGNITOR Program | Assigns new proteins to existing COGs | Included in COG database distribution [3] |

| Sequence Search | BLAST+ Suite | Protein sequence comparison and best-hit identification | https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [3] |

| Data Access | NCBI FTP Site | Download current and archived COG data | https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/COG/ [8] |

| Reference Data | RefSeq Database | Source of annotated protein sequences | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/ [8] |

| Pathway Resources | COG Pathway Collections | Curated sets of COGs involved in specific pathways | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/pathways/ [17] |

| Taxonomy Reference | NCBI Taxonomy Database | Standardized taxonomic classification | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy [8] |

| Functional Reference | UniProt Database | Detailed protein functional information | https://www.uniprot.org/ [8] |

| Structural Reference | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Protein structure information for COG members | https://www.rcsb.org/ [8] |

| Specialized Collections | arCOGs (Archaeal COGs) | Archaea-specific orthologous groups | https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/ [9] |

The COG database and its associated tools continue to evolve to meet the challenges of analyzing increasingly large genomic datasets. The 2024 update implemented several technical improvements, including the replacement of deprecated NCBI gene index (gi) numbers with stable RefSeq or GenBank/ENA/DDBJ coding sequence (CDS) accession numbers, ensuring long-term stability of protein identifiers [8]. Additionally, the database now provides comprehensive annotations with literature references and PDB links where available, enabling researchers to access detailed functional and structural information for COG members.

For researchers working with specific taxonomic groups, specialized COG collections such as arCOGs (Archaeal Clusters of Orthologous Genes) provide enhanced coverage and curation for particular lineages [9]. These specialized resources often include more detailed functional annotations and phylogenetic analyses tailored to the biological characteristics of the target organisms. The parallel development of these specialized collections alongside the comprehensive COG database ensures that researchers have access to appropriate tools regardless of their taxonomic focus.

The Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) database, an essential resource for the functional categorization of bacterial and archaeal genomes, has undergone a substantial expansion in its 2024 update. This release significantly broadens the database's phylogenetic scope and functional coverage, with dedicated efforts to incorporate protein families involved in bacterial secretion systems and to refine annotations for various protein families [11]. For researchers in microbial genomics and drug development, these developments provide enhanced capabilities for identifying potential therapeutic targets, such as virulence-associated secretion systems, and for generating more accurate functional predictions across diverse prokaryotic lineages. This Application Note details the novel features and provides protocols to leverage the updated COG resource effectively.

The 2024 update of the COG database represents a major scale-up in genomic coverage and functional content. The quantitative developments are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Changes in the COG 2024 Database Update

| Parameter | Previous Version | 2024 Update | Change | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Coverage | 1,309 species | 2,296 species (2,103 bacteria, 193 archaea) [11] | +987 species (+75%) | Broader phylogenetic representation; one genome per genus as a representative. |

| Total COGs | 4,877 | 4,981 [11] | +104 COGs | Incorporation of new protein families, primarily secretion systems. |

| New Functional Groups | Not Available | Secretion systems (Types II-X, Flp/Tad, Type IV pili) [11] | New | Enables systematic study of lineages possessing or lacking specific secretion systems. |

| Annotation Improvements | Previous baseline | rRNA/tRNA modification proteins, multi-domain signal transduction proteins, uncharacterized families [11] | Enhanced | More reliable functional predictions for these protein classes. |

The expansion to 2,296 genomes ensures that all bacterial and archaeal genera with 'complete genomes' in the NCBI databases as of November 2023 are represented, providing a comprehensive phylogenetic landscape for comparative analysis [11]. The addition of 104 new COGs is largely attributed to the systematic inclusion of protein families constituting key bacterial secretion systems. This allows researchers to straightforwardly identify and examine prokaryotic lineages that encompass—or lack—a particular secretion system, a critical feature for studying bacterial pathogenesis and intercellular communication [11].

Experimental Protocol: Profiling Secretion Systems in a Novel Genome

This protocol describes a standard methodology for using the updated COG database to identify and characterize secretion system genes in a newly sequenced bacterial genome.

Materials and Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for COG Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequence File | Input data for functional annotation. | A FASTA file (.faa) of the predicted protein sequences from your genome of interest. |

| COG Database | Reference database of Clusters of Orthologous Groups. | Downloaded from the NCBI FTP site: https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/COG/ [11]. |

| Sequence Comparison Tool | Software for aligning query sequences against the COG database. | BLAST+ suite (blastp) or DIAMOND (diamond blastp for accelerated searching) [18]. |

| COGNITOR or Similar Algorithm | Program to assign proteins to COGs based on the consistency of genome-specific best hits. | The method is embedded in the COG database resources and website [3]. |

| Annotation Scripts (Python/R) | Custom scripts for parsing results and generating summary statistics and visualizations. | -- |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation:

- Obtain the complete set of predicted protein sequences from your target genome in FASTA format (

genome_proteins.faa). - Download the latest COG database files, including the multiple sequence alignments and functional annotations, from the official NCBI resource (

https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/COG/[11]).

- Obtain the complete set of predicted protein sequences from your target genome in FASTA format (

Sequence Comparison:

- Use

diamond blastporblastpto compare your query proteins against the COG protein sequence database. - Example DIAMOND command:

- The

--more-sensitiveflag is recommended for improved accuracy, as noted in studies on protein sequence comparison benchmarks [18].

- Use

COG Assignment with COGNITOR Logic:

- The core principle of COG assignment involves identifying consistent, genome-specific best hits (BeTs). A protein is assigned to a COG if it has a minimum of two or three best hits to different proteins within that same COG [3].

- This process can be performed via the online COG resource at

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/COG[11], which automates the COGNITOR logic, or by implementing the algorithm locally.

Analysis of Secretion System COGs:

- From the full set of COG assignments for your genome, filter the results to focus on the newly added secretion system COGs (Types II through X, Flp/Tad, and Type IV pili) [11].

- Construct a presence-absence matrix for these systems across your genomes of interest to identify potential virulence factors or unique adaptations.

Data Interpretation and Visualization:

- Generate a bar plot or a heatmap to visualize the distribution of different secretion system types across compared genomes.

- Functionally categorize the identified COGs and create a pie chart to represent the functional landscape of your genome, highlighting the prevalence of secretion systems.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this protocol:

Accessing and Utilizing the Enhanced Annotations

Beyond the new secretion system COGs, the 2024 update provides improved annotations for several protein families critical for understanding fundamental cellular processes.

- rRNA and tRNA Modification Proteins: Refined annotations allow for more precise mapping of the cellular machinery that modifies RNA, which is crucial for proper protein synthesis and can be a target for antibacterial drugs [11].

- Multi-domain Signal Transduction Proteins: Enhanced classification of these complex proteins, often involving multiple domains like kinases and response regulators, improves the understanding of bacterial signal transduction networks [11].

- Previously Uncharacterized Families: A number of protein families that lacked clear functional predictions have now been characterized, reducing the "unknowns" in genome annotation and opening new avenues for research [11].

To access these annotations, researchers can use the online portal to browse specific COGs or download the complete annotation files. The integration of these improved annotations into automated analysis pipelines will significantly increase the accuracy of functional genomic studies. The following diagram outlines the logical relationship between different levels of functional analysis enabled by the updated COG database.

The 2024 update of the COG database marks a significant advancement, providing researchers with a more powerful and precise tool for the functional categorization of prokaryotic genomes. The strategic expansion to include secretion systems and improve annotations directly empowers studies in bacterial pathogenesis, cellular communication, and metabolic potential. By following the detailed protocols and utilizing the resources outlined in this document, scientists and drug development professionals can systematically uncover the functional blueprint of bacterial genomes, accelerating the discovery of novel biological mechanisms and therapeutic targets. The updated COG database is available at the NCBI website and FTP site [11].

Practical Implementation: COG Analysis workflows for Genome Annotation and Functional Prediction

The Database of Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COGs) is an established resource for the functional annotation of proteins from completely sequenced bacterial and archaeal genomes based on evolutionary relationships [8] [3]. Originally created in 1997, the COG database classifies proteins into orthologous groups, which are lineages of genes that diverged after a speciation event and typically retain the same function across different species [3]. This classification provides a robust framework for transferring functional information from characterized proteins to uncharacterized orthologs in newly sequenced genomes, making it an indispensable tool for comparative genomic analysis. The most recent 2024 update includes proteins from 2,296 species (2,103 bacteria and 193 archaea), substantially expanding its coverage to represent all bacterial and archaeal genera with completely sequenced genomes available in RefSeq as of November 2023 [8].

For researchers investigating bacterial genome evolution, pathogenesis, or metabolic pathways, the COG system offers several unique advantages. The database construction relies on the identification of consistent patterns of sequence similarity across multiple genomes, which helps in distinguishing orthologs from paralogs—a critical distinction for accurate functional prediction [3]. The COGs also provide a phylogenetic profile for each group, showing the pattern of species presence or absence, which can reveal important evolutionary events such as horizontal gene transfer or lineage-specific gene loss [19] [3]. These features make the COG database particularly valuable for studies aimed at understanding functional conservation and diversification across microbial taxa, as demonstrated in recent applications ranging from rhizosphere microbiome analysis [20] to studies of genomic islands and horizontal gene transfer [19].

Database Access Methods

NCBI Web Portal

The primary web interface for the COG database is maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/ [5]. This portal provides user-friendly search capabilities and multiple entry points for accessing COG information, making it the recommended starting point for most research applications.

The search functionality supports several query types, which are summarized in the table below:

Table 1: COG Search Options Available via the NCBI Web Portal

| Search Type | Example Query | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| COG Identifier | COG0002 or 105 |

Direct access to specific COG entries |

| Protein Name | polymerase |

Finding COGs related to specific proteins |

| Taxonomic Category | Mollicutes |

Exploring COG distribution in taxonomic groups |

| Organism Name | Aciduliprofundum_boonei_T469 |

Finding COGs in specific organisms |

| Metabolic Pathway | Arginine biosynthesis |

Identifying COGs associated with specific pathways |

| Assembly Accession | GCA_000091165.1 |

Linking COGs to specific genome assemblies |

| Protein Identifier | prot:WP_011012300.1 |

Finding COG membership of specific proteins |

A search for COG0002 on the portal returns detailed information about the N-acetyl-gamma-glutamylphosphate reductase (ArgC) involved in arginine biosynthesis, including statistics showing its presence in 1,863 genes across 1,867 organisms, a representative PDB structure (3DR3), and taxonomic distribution across archaeal and bacterial lineages [21]. The interface also provides direct links to download COG data and access related protein structures and sequences.

FTP Site Structure and Navigation

For bulk downloading or programmatic access, the COG database is available through the NCBI FTP site at https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/COG/ [8]. This repository contains both the current release (COG2024) and archived previous versions, providing comprehensive data for large-scale analyses or comparative studies across different database versions.

The FTP site organization follows a logical structure, with key directories and files including:

- COG2024/: Directory containing the most recent database release

- data/: Subdirectory with core data files

- cog-24.org.tab: File listing all organisms included in the current release

- Archived releases/: Folder containing previous versions for historical comparison

Additionally, the broader NCBI Genomes FTP site (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/) provides complementary annotation files for individual genomes, which can be correlated with COG classifications [22]. These include protein FASTA files (*_protein.faa.gz), gene ontology annotations (*_gene_ontology.gaf.gz), and feature tables (*_feature_table.txt.gz) that offer detailed information about genes and their products.

Selecting the Appropriate Access Method

The choice between web portal and FTP access depends on the specific research requirements:

- Web Portal: Ideal for targeted queries, exploratory analysis, and visualization of individual COG characteristics, taxonomic distribution, and functional annotations.

- FTP Site: Better suited for large-scale data mining, comparative genomics projects, integration with local bioinformatics pipelines, and accessing complete database snapshots.

For most research scenarios involving the functional categorization of bacterial genomes, a combined approach is recommended: using the web interface for initial exploration and validation, followed by FTP downloads for comprehensive analysis.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: COG-Based Functional Annotation of Bacterial Genomes

This protocol describes a standard workflow for annotating protein sequences from bacterial genomes using the COG database, enabling functional categorization and comparative analysis.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| COG Database | Provides reference set of orthologous groups for classification [8] |

| COGNITOR Program | Algorithm for fitting new proteins into existing COGs [3] |

| BLAST Suite | Performs sequence similarity searches against COG members [3] |

| Protein Sequence Dataset | Query sequences from target bacterial genome(s) |

| Perl/Python Scripts | For parsing results and automating analysis steps |

Procedure

Data Acquisition

- Download the complete set of COG protein sequences and group definitions from the NCBI FTP site (COG2024 release) [8].

- Retrieve protein sequences from the target bacterial genome(s) in FASTA format, either from NCBI Genomes FTP or your own sequencing data.

Sequence Comparison

- Perform an all-against-all sequence comparison between query proteins and COG reference sequences using BLASTP with an E-value cutoff of 0.001 [3].

- For large datasets, consider using accelerated alternatives such as DIAMOND or USEARCH while maintaining comparable sensitivity.

Orthology Assignment

- Identify genome-specific best hits (BeTs) for each query protein against the COG database.

- Apply the COGNITOR algorithm, which assigns a protein to a COG if it has consistent best hits to multiple members of that COG [3]. The current standard requires at least three consistent best hits to minimize false assignments.

Functional Transfer

- Assign the functional annotation of the COG to the query protein, noting that this transfer is most reliable for simple COGs without paralogs [3].

- For COGs containing paralogs, exercise caution and consider additional evidence such as domain architecture or phylogenetic analysis before making specific functional predictions.

Validation and Quality Control

- Verify that multidomain proteins are correctly classified; consider splitting sequences into domains and repeating the analysis if necessary [3].

- Check the phylogenetic pattern of the assigned COG to ensure it is consistent with the evolutionary history of the organism.

Protocol 2: Identification of Pathway-Specific COG Enrichment

This protocol enables researchers to identify COGs that are significantly enriched in specific metabolic pathways, which is particularly useful for understanding the genetic basis of specialized metabolic capabilities across bacterial taxa.

Materials and Reagents

- COG Database with functional categories and pathway annotations [8]

- KEGG or MetaCyc Pathway Database for reference pathway definitions

- Statistical Computing Environment (R or Python with pandas, scipy)

- Genome Annotation Files for target organisms

Procedure

Pathway Definition

Genome Selection

- Identify bacterial genomes of interest using the NCBI assembly database [22].

- Download COG annotations for these genomes from the NCBI FTP site or generate them using Protocol 1.

Enrichment Analysis

- Create a binary matrix indicating presence/absence of each COG in each genome.

- For the pathway of interest, calculate the frequency of each associated COG across the genome set.

- Compare these frequencies to the background distribution of all COGs using statistical tests such as Fisher's exact test or chi-square test.

Interpretation

- Identify COGs that are significantly enriched (p < 0.05 with multiple testing correction) in the target pathway.

- Consider the phylogenetic distribution of enriched COGs to identify potential horizontal gene transfer events or lineage-specific adaptations [19].

Table 3: Example Results from COG Enrichment Analysis of Arginine Biosynthesis

| COG ID | COG Name | Frequency in Pathway | Background Frequency | p-value | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG0002 | ArgC | 85% | 2% | <0.001 | N-acetyl-gamma-glutamylphosphate reductase [21] |

| COG0116 | ArgG | 82% | 3% | <0.001 | Argininosuccinate synthase |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Resources for COG-Based Genomic Analysis

| Resource | Description | Access Method |

|---|---|---|