Advanced Strategies for Contig Binning of Closely Related Microbial Strains

Resolving closely related strains in metagenomic samples is a significant challenge in microbial genomics, with implications for understanding pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance, and ecosystem function.

Advanced Strategies for Contig Binning of Closely Related Microbial Strains

Abstract

Resolving closely related strains in metagenomic samples is a significant challenge in microbial genomics, with implications for understanding pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance, and ecosystem function. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians, covering the foundational challenges of strain-level binning, modern computational methods leveraging deep learning and advanced clustering, strategies for optimizing performance on complex real-world data, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing insights from the latest benchmarking studies and tool developments, we offer a practical roadmap for recovering high-quality, strain-resolved metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) to drive discoveries in clinical and biopharmaceutical research.

The Fundamental Challenge: Why Closely Related Strains Elude Standard Binning

Metagenomic binning is a fundamental computational process in microbiome research where sequenced DNA fragments (contigs) are clustered into groups, or "bins," that ideally represent the genomes of individual microbial populations within a sample [1] [2]. This technique is crucial for moving beyond simple community profiling to the reconstruction of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs), allowing scientists to study uncultured microorganisms directly from environmental, clinical, or industrial samples [3].

The resolution of binning can vary significantly, ranging from broad taxonomic groups to highly refined strain-level populations. The challenge of distinguishing between closely related strains—often differing by only a few nucleotides—represents one of the most significant frontiers in metagenomic analysis today [4]. Success in this endeavor directly impacts our ability to understand microbial ecology, identify pathogenic variants, and discover novel biological functions.

Fundamental Binning Approaches and Mechanisms

Metagenomic binning methods leverage specific genomic features to cluster sequences. The table below summarizes the primary approaches and their operating principles.

Table 1: Fundamental Metagenomic Binning Approaches

| Binning Approach | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Common Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition-Based | Utilizes inherent genomic signatures like k-mer frequencies (e.g., tetranucleotide patterns) and GC content [2]. | Effective for distinguishing evolutionarily distant genomes. | TETRA, CompostBin [2] |

| Abundance-Based (Coverage) | Groups sequences based on similar abundance (coverage) profiles across multiple samples [1] [2]. | Can separate genomes with similar composition but different abundance patterns. | - |

| Hybrid | Combines composition and abundance features to improve accuracy [1] [5]. | More robust and accurate than single-feature methods. | MetaBAT 2, MaxBin 2 [1] [5] |

| Supervised Machine Learning | Uses models trained on annotated reference genomes to classify sequences [1]. | High accuracy when reference data is available. | BusyBee Web [2] |

| Deep Learning & Contrastive Learning | Employs advanced neural networks to learn high-quality representations of heterogeneous data [5]. | Superior at integrating complex features and handling dataset variability. | COMEBin, VAMB, SemiBin [5] |

The Strain-Level Resolution Challenge

For researchers focusing on closely related strains, the standard binning process faces inherent limitations. Standard metagenome assemblers and binners struggle with populations that share >99% average nucleotide identity (ANI), often resulting in MAGs that are composite mosaics of multiple strains rather than pure haplotypes [4]. This occurs because:

- Complex Assembly Graphs: When highly similar strains are present, the assembly graph becomes excessively complex with many branching paths, which assemblers resolve by fragmenting the sequence into shorter contigs [4].

- Limited Binning Resolution: Most binning tools use features like tetranucleotide frequency, which are consistent across a species and lack the resolution to distinguish individual strains [4].

- Misassemblies: Conserved regions, such as antibiotic resistance genes or ribosomal RNA operons, exist in multiple genomic contexts. Assemblers tend to break contigs around these regions, further fragmenting the data and complicating strain separation [6] [7].

Advanced Tools for Enhanced Binning and Strain Resolution

To address these challenges, new computational frameworks have been developed. The following table benchmarks modern tools, including those designed for high-resolution tasks.

Table 2: Benchmarking of Advanced Binning and Strain-Resolution Tools

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Technology/Innovation | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| BASALT [3] | Binning & Refinement | Uses multiple binners with multiple thresholds, followed by neural network-based refinement and gap filling. | Recovers ~30% more MAGs than metaWRAP; produces MAGs with significantly higher completeness and lower contamination. |

| COMEBin [5] | Binning | Contrastive multi-view representation learning to integrate k-mer and coverage features. | Outperforms other binners, with an average 22.4% more near-complete genomes (>90% complete, <5% contaminated) on real datasets. |

| STRONG [4] | De Novo Strain Resolution | Resolves strains directly on assembly graphs using a Bayesian algorithm (BayesPaths), leveraging multi-sample co-assembly. | Validated on synthetic communities and real time-series data; matches haplotypes observed from long-read sequencing. |

| metaMIC [7] | Misassembly Identification & Correction | Machine learning (Random Forest) to identify and localize misassembly breakpoints using read alignment features. | Correcting misassemblies before binning improves subsequent scaffolding and binning results. |

Experimental Protocol: Strain-Resolved Metagenomics with STRONG

For researchers aiming to resolve strain-level variation, the STRONG pipeline provides a robust methodology [4].

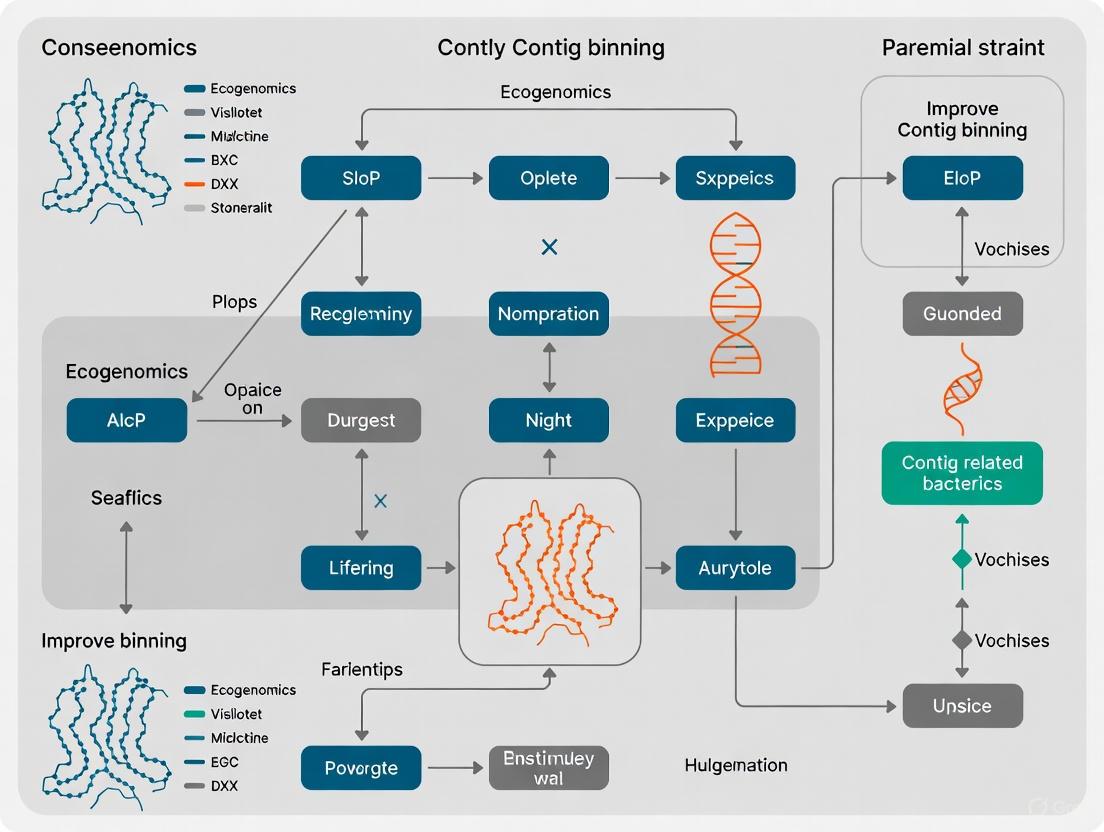

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the STRONG pipeline for strain resolution.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol:

Sample Preparation & Sequencing:

- Collect multiple metagenomic samples from a time series or cross-sectional study. The power of STRONG relies on the presence of the same strains across multiple related samples.

- Perform shotgun sequencing using Illumina technology to generate short reads.

Co-assembly:

- Input: Short-read files (FASTQ) from all samples.

- Software:

metaSPAdes. - Action: Co-assemble all samples together into a single set of contigs. This creates a comprehensive representation of the microbial community.

- Output: Assembled contigs (FASTA) and a high-resolution assembly graph (HRG).

Metagenomic Binning:

- Input: Contigs from Step 2.

- Software: Standard binning tools (e.g.,

MetaBAT 2,MaxBin 2). - Action: Bin contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). These MAGs will typically represent species-level groups.

- Output: Binned MAGs (FASTA files).

Strain Resolution with STRONG:

- Input: The coassembly graph (HRG) from Step 2 and the MAGs from Step 3.

- Software:

STRONGpipeline. - Action:

- For each MAG, STRONG extracts the sub-graphs corresponding to a set of universal single-copy core genes (SCGs).

- The

BayesPathsalgorithm analyzes the per-sample coverage of unitigs (graph nodes) within these SCG sub-graphs. - It probabilistically infers the number of strains, their specific haplotypes (sequences) on the SCGs, and their relative abundance in each sample.

- Output: Strain haplotypes and their abundance profiles across samples.

Troubleshooting Common Binning Problems

FAQ 1: My binning results show high contamination according to CheckM. What are the potential causes and solutions?

- Potential Cause 1: Misassembled Contigs. Chimeric contigs that combine sequences from different genomes are a major source of bin contamination [7].

- Solution: Run a misassembly detection tool like

metaMICon your contigs prior to binning.metaMICcan identify and correct these chimeric contigs by splitting them at the misassembly breakpoint, thereby improving bin purity [7]. - Potential Cause 2: True Biological Mixture. The sample may contain multiple closely related strains with similar sequence composition and abundance, causing binners to group them into a single, "contaminated" bin [4].

- Solution: Employ strain-resolution tools like

STRONGorDESMANon the affected MAGs. These tools can deconvolute the mixture into distinct haplotypes, effectively resolving the contamination [4].

FAQ 2: My assembly is highly fragmented, and many short contigs remain un-binned. How can I improve this?

- Potential Cause: Low and Uneven Sequencing Coverage. Low-abundance genomes and genomic regions with unusual sequence composition (e.g., horizontal gene transfer events) often fail to assemble and bin properly [1] [6].

- Solutions:

- Increase Sequencing Depth: Sequence more deeply to improve coverage uniformity across all genomes.

- Use Advanced Binners: Tools like

BASALTandCOMEBinare specifically designed to recruit more of these un-binned and fragmented sequences into MAGs by using sophisticated refinement modules and feature integration [3] [5]. - Leverage Long Reads: If possible, incorporate long-read sequencing data (e.g., Nanopore, PacBio). Hybrid assemblies or using long reads for polishing can dramatically improve contiguity, which in turn facilitates more accurate binning [3].

FAQ 3: How can I be confident that my "high-quality" MAG isn't a composite of multiple strains?

- Solution:

- Internal Validation: Analyze the MAG for evidence of strain mixture. A key indicator is the presence of an unusually high density of heterozygous single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) on contigs, which suggests the presence of multiple haplotypes [4].

- Use Specialized Tools: Apply a strain-resolver like

STRONG[4] to the MAG. If the tool infers the presence of two or more distinct haplotypes for the single-copy core genes, your MAG is likely a composite. - Independent Validation: If resources allow, validate the inferred haplotypes by comparing them to sequences obtained from long-read sequencing of the same sample, which can natively span strain-variable regions [4].

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Databases for Metagenomic Binning

| Category | Item/Software | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly | metaSPAdes [2] [4], MEGAHIT [2] | Reconstructs short reads into longer contiguous sequences (contigs). |

| Core Binning | MetaBAT 2 [1], COMEBin [5], VAMB [5] | Clusters contigs into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). |

| Strain Resolution | STRONG [4], DESMAN [4] | Deconvolutes MAGs into individual strain haplotypes. |

| Quality Control | CheckM [1], metaMIC [7] | Assesses MAG completeness/contamination and identifies misassemblies. |

| Reference Databases | GTDB [8], NCBI RefSeq [8] | Provides curated reference genomes for taxonomic classification and validation. |

| Benchmarking | CAMI (Critical Assessment of Metagenome Interpretation) [3] [6] | Provides standardized datasets and challenges for tool evaluation. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the main computational challenges in binning contigs from complex microbiomes? The primary obstacles are strain heterogeneity (the presence of closely related strains), imbalanced species abundance (where a few species are dominant and many are rare), and genomic plasticity (structural variations like insertions, deletions, and horizontal gene transfer). These factors distort feature distributions used for binning, such as k-mer frequencies and coverage profiles, making it difficult to cluster contigs accurately into pure, high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [9].

2. My binner performs well on simulated data but poorly on a real human gut sample. Why? Real environmental samples, like those from the human gut, often have more imbalanced species distributions and higher strain diversity than simulated datasets. This can cause binners that rely on single-copy gene information or assume balanced abundances to fail. Methods specifically designed for these challenges, such as those employing two-stage clustering and reassessment models, are more robust for natural microbiomes [9].

3. How does strain heterogeneity specifically affect contig binning? Strain heterogeneity poses a significant challenge for distinguishing contigs at the species or strain level using k-mer frequencies, which are more effective at the genus level. Furthermore, closely related strains (with an Average Nucleotide Identity of ≥95%) can have very similar coverage profiles across samples, making it difficult to resolve them into separate, high-quality bins [5] [10].

4. Can I use short-read binners for long-read metagenomic assemblies? It is not recommended. Long-read sequencing produces assemblies that are more continuous and have richer information, enabling the assembly of low-abundance genomes. The properties of these assemblies differ from short-read assemblies, making dedicated long-read binners more suitable [9].

5. What is the benefit of using a contrastive learning model in binning? Contrastive learning models, such as those used in COMEBin and SemiBin2, learn an informative representation of contigs by pulling similar instances (e.g., fragments from the same contig) closer together in the embedding space and pushing dissimilar ones apart. This approach leads to higher-quality embeddings of heterogeneous features (coverage and k-mers), which in turn improves clustering performance, especially on real datasets [5] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Recovery of Genomes from Rare Species

Potential Cause: The microbial community has a highly imbalanced species distribution, where standard clustering algorithms struggle to identify clusters for low-abundance species.

Solutions:

- Use Binners Designed for Imbalanced Data: Employ tools like LorBin, which uses a two-stage multiscale adaptive clustering approach (DBSCAN and BIRCH) with a reclustering decision model. This is specifically designed to handle the "long-tail" distribution of species abundance in natural microbiomes [9].

- Leverage Multi-Sample Binning: If multiple related samples are available, use a multi-sample binning approach. Contigs from a low-abundance genome in one sample might have higher coverage in another, providing a stronger signal for binning [10].

Problem: Inability to Separate Closely Related Strains

Potential Cause: The binning tool's feature set (e.g., standard k-mer frequencies and coverage) is not sensitive enough to discriminate between genomes with high sequence similarity.

Solutions:

- Utilize Advanced Feature Learning: Implement binners that use deep learning to create better contig embeddings. COMEBin, for instance, uses contrastive multi-view representation learning, which has been shown to improve performance on complex datasets [5].

- Apply Post-binning Strain Analysis: For known species, use a dedicated strain-tracking tool like SynTracker after binning. SynTracker uses genome synteny (the order of genes or sequence blocks) to compare strains and is highly sensitive to the structural variations that often characterize closely related strains [11].

Problem: Bins Have High Contamination or Are Too Fragmented

Potential Cause: Genomic plasticity, such as horizontal gene transfer or the presence of mobile genetic elements, can lead to regions in a genome having divergent sequence compositions or coverage, confusing the binning algorithm.

Solutions:

- Employ Robust Clustering Algorithms: Choose binners that use sophisticated clustering methods. The Leiden algorithm (used in COMEBin) and two-stage clustering (used in LorBin) have been shown to produce more robust bins [5] [9].

- Integrate Assembly Graph Information: Some modern binning pipelines can incorporate information from the assembly graph, which represents links between contigs. This can help in assigning horizontally transferred elements more accurately [10].

Benchmarking Data of Advanced Binners

The following table summarizes the performance of state-of-the-art binning tools as reported in recent benchmarking studies, highlighting their effectiveness in overcoming key obstacles.

| Tool | Core Methodology | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| COMEBin [5] | Contrastive multi-view representation learning | Outperformed others on 14/16 co-assembly datasets; average improvement of 22.4% in near-complete bins on real datasets. Effective with heterogeneous data. |

| LorBin [9] | Two-stage adaptive DBSCAN & BIRCH clustering; VAE features | Unsupervised; generated 15–189% more high-quality MAGs in natural microbiomes; excels with imbalanced abundance and novel taxa. |

| SemiBin2 [10] | Self-supervised contrastive learning | One of the top performers in overall binning accuracy; effective in both single- and multi-sample binning modes. |

| GenomeFace [10] | Pretrained networks on coverage and k-mers | Achieved the highest contig embedding accuracy in independent benchmarks on CAMI2 datasets. |

| MetaBAT2 [9] [10] | Geometric mean of composition/abundance distances | Widely used and known for its computational speed, though may be less effective on complex, imbalanced samples. |

Experimental Protocol for Binning Evaluation

Below is a detailed methodology for a standard benchmarking experiment to evaluate the performance of a contig binner, for instance, on a dataset like CAMI II.

1. Dataset Preparation:

- Input: Obtain a benchmark dataset with a known ground truth, such as the CAMI II simulated datasets (e.g., Marine, Strain-madness) [5] [10].

- Assembly: If starting from reads, assemble them using a tool like MEGAHIT to generate contigs. Note that assembly quality (GSA vs. MA) significantly impacts final binning quality [5].

2. Feature Extraction and Binning Execution:

- Run Binners: Execute the binning tools (e.g., COMEBin, LorBin, SemiBin2) on the assembled contigs according to their documentation.

- Key Parameters:

- For COMEBin, the method uses data augmentation to create multiple views of each contig and employs contrastive learning. The Leiden algorithm is used for clustering, adapted with single-copy gene information [5].

- For LorBin, the tool uses a variational autoencoder for feature extraction. It then applies a two-stage clustering process: first with multiscale adaptive DBSCAN, and then with BIRCH on the unclustered contigs, guided by an assessment-decision model [9].

3. Quality Assessment and Analysis:

- Evaluate Bins: Use tools like CheckM or similar to assess the completeness and contamination of the resulting MAGs against the known ground truth.

- Metrics: Calculate the number of high-quality bins (>90% completeness, <5% contamination), the F1-score based on base pairs, and the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) to measure clustering accuracy [5] [10].

Workflow for Binning Benchmarking

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software "reagents" essential for conducting advanced contig binning research.

| Tool / Resource | Function |

|---|---|

| CAMI II Datasets | Provides standardized simulated and real metagenomic benchmarks with known ground truth for fair tool evaluation [5] [10]. |

| CheckM | Assesses the quality of genome bins by quantifying completeness and contamination using single-copy marker genes [5]. |

| Anvi'o | An integrated platform for metagenomics, used for visualization, binning refinement, and analysis of contigs, even without mapping data [12]. |

| SynTracker | A strain-tracking tool that uses synteny analysis, complementing SNP-based methods to detect strain-level variation driven by structural changes [11]. |

| d2SBin | A post-binning refinement tool that uses a relative k-tuple dissimilarity measure (d2S) to improve bins from other methods on single samples [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main limitations of k-mer frequency and coverage in metagenomic binning?

While k-mer frequencies (typically tetramers) are effective for distinguishing contigs at the genus level, they often lack the resolution to differentiate between closely related species or strains, as these organisms share highly similar genomic sequences [10] [2]. Coverage profiles, which represent the abundance of contigs across samples, provide complementary information but can fail when different strains have similar abundance patterns or when dealing with low-abundance organisms where coverage data is noisy [5] [14].

Why is binning closely related strains so challenging?

Closely related strains, such as those found in the CAMI "strain-madness" dataset, have high genomic similarity (Average Nucleotide Identity often ≥95%) and very similar k-mer compositions [10] [5]. Traditional binning tools struggle because the subtle genomic variations between strains are not sufficiently captured by standard k-mer and coverage features, leading to strains from the same species being incorrectly grouped into a single bin [10].

What are the signs that my binning results are suffering from these limitations?

Key indicators include: bins with abnormally high estimated completeness (>100%) and contamination, which suggest multiple closely related genomes have been grouped together; the inability to separate strains known to be present from prior knowledge; and bins that contain a disproportionate number of single-copy marker genes, indicating the pooling of multiple genomes [12] [5].

Which advanced methods can overcome these limitations?

Newer deep learning-based binners use sophisticated techniques like contrastive learning (e.g., COMEBin, SemiBin2) to learn higher-quality contig embeddings. These methods employ data augmentation and self-supervised learning to better capture subtle genomic patterns that distinguish closely related strains [10] [5]. Other approaches integrate additional data types, such as assembly graphs or taxonomic annotations, to improve separation [10].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Poor Separation of Closely Related Strains

Description The binning tool fails to resolve individual strains from a group of closely related organisms, resulting in MAGs (Metagenome-Assembled Genomes) that are chimeric mixtures of multiple strains.

Diagnosis Steps

- Check Bin Quality: Run CheckM or similar quality assessment tools. Bins with high completeness but also high contamination (e.g., >5-10%) may contain multiple strains [1].

- Analyze Single-Copy Marker Genes: Inspect the number of single-copy marker genes in your bins. A count significantly greater than one for many markers strongly indicates merged strains [12] [5].

- Visualize Bins: Use a tool like Anvi'o to visualize the binning results. Contigs from different strains may form distinct sub-clusters within a single bin based on tetra-nucleotide frequency, which can be visually identified [12].

Solutions

- Switch to Advanced Binners: Use a state-of-the-art deep learning binner that uses contrastive learning.

- COMEBin: Employs contrastive multi-view representation learning, generating multiple fragments of each contig to create robust embeddings. It has demonstrated superior performance in recovering near-complete genomes from complex datasets, including those with closely related strains [5].

- SemiBin2: Also uses contrastive learning and can leverage environment-specific pre-trained models (e.g., for human gut, soil) to improve binning accuracy [10].

- Optimize Binning Strategy:

- For low-coverage datasets, consider co-assembly multi-sample binning (pooling reads from multiple samples before assembly) to increase assembly coverage.

- For high-coverage samples, multi-sample binning (individual assembly per sample, then collective binning using multi-sample coverage) is often more effective [10].

- In multi-sample binning, splitting the embedding space by sample before clustering has been shown to enhance performance compared to the standard method of splitting final clusters by sample [10].

- Apply Post-binning Reassembly: For bins identified as containing mixed strains, extract the associated reads and perform a reassembly focused solely on that population. This can sometimes yield better-resolved contigs for the individual strains [10].

Problem: Low-Quality Bins from a Complex Community

Description The binning process results in a low number of high-quality bins, with many fragmented or incomplete MAGs, especially from a microbial community with high diversity and strain heterogeneity.

Diagnosis Steps

- Verify Input Data Quality: Ensure your contigs are of sufficient length and that coverage calculations are accurate. Short or highly fragmented contigs are difficult to bin correctly [1].

- Benchmark on Gold-Standard Data: Test your binning pipeline on a benchmark dataset like CAMI2, where the ground truth is known, to isolate whether the problem is with the data or the method [10] [15].

Solutions

- Leverage Multiple Samples: If available, use multi-sample coverage information instead of single-sample binning. Abundance profiles across multiple samples provide a powerful signal for separating genomes that is not available in a single sample [10] [5].

- Utilize Post-Binning Refinement: After an initial binning step, use refinement tools that can reassign contigs between bins based on consistency checks (e.g., using single-copy gene information or coverage profiles) to improve bin purity and completeness [2].

Performance Comparison of Binning Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of various binning methods on datasets containing closely related strains, based on benchmark studies. A higher number of recovered high-quality genomes indicates better performance.

| Binning Method | Core Algorithm | Number of Near-Complete Bins Recovered (Strain-Madness Dataset Example) | Key Strengths / Limitations for Strain Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| COMEBin [5] | Contrastive Multi-view Learning | Best Overall Performance | Effectively uses data augmentation to learn robust embeddings; handles complex datasets well. |

| SemiBin2 [10] | Contrastive Learning | High | Uses contrastive learning; offers pre-trained models for specific environments. |

| GenomeFace [10] | Pretrained Networks (k-mer & coverage) | High Embedding Accuracy | Achieves high embedding accuracy; uses a transformer model for coverage data. |

| VAMB [10] | Variational Autoencoder | Moderate | A foundational deep learning binner; outperformed by newer contrastive methods. |

| MetaBAT2 [10] [1] | Statistical Framing (TF + Coverage) | Moderate | Widely used, computationally efficient; struggles with high strain diversity. |

| MaxBin2 [5] | Expectation-Maximization | Lower | Performance heavily influenced by assembly quality. |

Experimental Protocol: Contrastive Learning for Strain Resolution

The following workflow is adapted from the methodology used by COMEBin [5] and other contrastive learning binners to address the challenge of binning closely related strains.

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Protocol

Input Feature Preparation

- Coverage Profile: Map all sequencing reads from every sample back to the contigs using a read mapper (e.g., Bowtie2, BWA). Calculate the average depth of coverage at each position for every contig-sample pair. Normalize the coverage values across samples [1].

- k-mer Frequency: For each contig, compute its normalized frequency of all possible 4-mers (tetramers). Combine the counts of each k-mer with its reverse complement to reduce dimensionality [2].

Data Augmentation (Creating Multiple Views)

- For each contig, generate multiple "views" or fragments by splitting the contig into shorter segments (e.g., two halves) [5].

- Recompute the coverage and k-mer frequency vectors for each of these fragments. These fragments form positive pairs for the contrastive learning model.

Contrastive Multi-view Representation Learning

- Architecture: Use a neural network with two separate modules to process the heterogeneous features.

- Coverage Module: A dedicated sub-network (e.g., multi-layer perceptron) processes the multi-sample coverage vector to generate a fixed-dimensional coverage embedding.

- Composition Module: A separate sub-network processes the k-mer frequency vector to generate a k-mer embedding.

- Training: The model is trained using a contrastive loss function (e.g., InfoNCE). The objective is to minimize the distance between the embeddings of augmented pairs (views from the same original contig) in the latent space while maximizing the distance from embeddings of other, unrelated contigs [5].

- Architecture: Use a neural network with two separate modules to process the heterogeneous features.

Clustering and Refinement

- Embedding Concatenation: Combine the learned coverage and k-mer embeddings into a single, unified representation for each contig.

- Community Detection: Cluster the contigs in this unified embedding space using a community detection algorithm like the Leiden algorithm. This algorithm is effective at identifying the group structure in networks [5].

- Optimization: The clustering process can be optimized using information from single-copy marker genes and contig length to help determine appropriate cluster resolutions and merge/split clusters for optimal completeness and contamination scores [10] [5].

| Tool / Resource | Function in Binning Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CAMI2 Benchmark Datasets [10] [15] | Provides gold-standard simulated and real metagenomes with known taxonomic origins for rigorous tool evaluation. | Essential for validating new binning methods and fair comparisons. Includes complex "strain-madness" scenarios. |

| CheckM / CheckM2 [1] | Assesses the quality and completeness of MAGs by analyzing the presence and multiplicity of single-copy marker genes. | The standard for evaluating binning outcomes. High contamination scores flag potential strain merging. |

| Anvi'o [12] | An integrated platform for interactive visualization, manual refinement, and analysis of metagenomic bins. | Useful for exploratory analysis and manual curation of bins suspected to contain multiple strains. |

| MetaBAT2 [10] [1] | A robust, traditional binner that is fast and widely used. Serves as a good baseline for performance comparison. | While not the best for strain resolution, its speed makes it useful for initial explorations and benchmarking. |

| Bowtie2 / BWA | Short-read aligners used to map sequencing reads back to assembled contigs, generating the essential coverage profiles. | A critical step for generating input for coverage-based and hybrid binning methods. |

| SemiBin2 Pre-trained Models [10] | Environment-specific models (e.g., human gut, soil) that can be used for binning without training a new model. | Can significantly improve results when working with samples from these pre-defined environments. |

The Impact of Assembly Quality on Downstream Binning Success

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most critical factor in assembly that impacts my ability to bin closely related strains? Assembly contiguity is paramount. Highly fragmented assemblies provide shorter contigs that lack sufficient taxonomic signals (like tetranucleotide frequency) for binning algorithms to reliably distinguish between closely related strains. Tools like metaSPAdes have been shown to produce larger, less fragmented assemblies, which provide more sequence context for accurate binning [16].

FAQ 2: Should I use co-assembly or single-sample assembly for a time-series study of microbial strains? For longitudinal studies, co-assembly (pooling multiple metagenomes) is often superior. It provides greater sequence depth and coverage, which is crucial for assembling low-abundance organisms. Furthermore, it enables the use of differential coverage across samples as a powerful feature for binning algorithms to disentangle strain variants [16]. Single-sample assemblies may preserve strain variation but often suffer from lower coverage, making binning more difficult [16].

FAQ 3: Which combination of assembler and binning tool is recommended for recovering low-abundance or closely related strains? Research indicates that the metaSPAdes assembler paired with the MetaBAT 2 binner is highly effective for recovering low-abundance species from complex communities [16] [17]. Another study found that MEGAHIT-MetaBAT2 excels in recovering strain-resolved genomes [17]. Using multiple binning approaches on a robust metaSPAdes co-assembly can help recover unique MAGs from closely related species that might otherwise collapse into a single bin [16].

FAQ 4: My binning tool is struggling with contamination and incomplete genomes. What can I do? This is a common problem. The solution often lies in improving the input assembly. Focus on assembly strategies that increase contiguity (e.g., using metaSPAdes). After binning, use refinement and evaluation tools like CheckM and DAS Tool to assess genome quality (completeness and contamination) and create a non-redundant set of high-quality bins [16] [1].

FAQ 5: How does sequencing technology (short-read vs. long-read) impact assembly quality for binning? Short-read (SR) technologies (e.g., Illumina) are less error-prone but struggle with complex genomic regions like repeats, leading to fragmented assemblies. Long-read (LR) technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) produce more contiguous assemblies and better recover variable genome regions, which is critical for analyzing elements like defense systems or integrated viruses. In complex environments like soil, LR sequencing can complement SR by improving contiguity and recovering regions missed by SR assemblies [18]. The choice depends on your sample's DNA quality/quantity and the specific genomic features of interest.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Binning Resolution for Closely Related Strains

Description The resulting Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) are overly broad, containing a mixture of contigs from multiple closely related strains, or unique strains collapse into a single MAG.

Diagnosis Steps

- Check Assembly Metrics: Examine the contiguity of your assembly. A low N50 value and a high number of total contigs indicate a fragmented assembly, which is the primary culprit.

- Verify Binning Features: Ensure your binning tool is using both sequence composition (e.g., tetranucleotide frequency) and differential coverage across multiple samples. Coverage information is vital for separating strains [2].

- Inspect Binning Software: Confirm you are using a modern binning tool like MetaBAT 2, which has been shown to outperform earlier alternatives in both accuracy and computational efficiency [1].

Solutions

- Solution 1: Optimize Assembly Strategy. Implement a co-assembly strategy using metaSPAdes to create larger, less fragmented contigs. Studies on drinking water and human gut metagenomes have shown this combination with MetaBAT2 to be highly effective [16] [17].

- Solution 2: Leverage Multiple Binners. Run several binning tools (e.g., MetaBAT2, MaxBin, CONCOCT) on your high-quality assembly and use a bin refinement tool like DAS Tool or MetaWRAP to generate a superior, non-redundant set of bins from the individual results [16].

- Solution 3: Utilize Long-Read Data. If possible, incorporate long-read sequencing data. Long-read assemblers like metaFlye can produce more contiguous assemblies, helping to resolve repetitive regions that confuse short-read assemblers and binning tools [18].

Problem: Low Recovery of Low-Abundance Genomes

Description The binning process fails to reconstruct genomes from microbial species that are present in the community but at low relative abundance (<1%).

Diagnosis Steps

- Assess Sequencing Depth: Check the average coverage of your assembled contigs. Low-abundance genomes will have contigs with consistently low coverage.

- Evaluate Assembly Completeness: Use a tool like CheckM to see if your bins are largely incomplete. Low-coverage regions often fail to assemble, leading to incomplete genomes for rare organisms [1].

- Review Assembly Method: Single-sample assemblies are particularly susceptible to missing low-abundance genomes due to insufficient coverage [16].

Solutions

- Solution 1: Implement Deep Co-assembly. Pool sequencing data from multiple related samples to perform a deep co-assembly. This increases the effective sequencing depth for low-abundance community members, making their contigs easier to assemble and bin [16] [19].

- Solution 2: Apply a Targeted Binning Approach. Use a binner known to be sensitive to low-abundance species, such as MetaBAT 2 in combination with a metaSPAdes co-assembly [17].

- Solution 3: Employ Advanced Binning Features. Some modern binning tools can incorporate other biological information, such as graph structures of sequences or the presence of special genes, to improve binning accuracy for difficult sequences [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Protocol: Co-assembly and Binning for Strain-Resolved MAGs

This protocol is designed for recovering high-quality, strain-resolved MAGs from multiple metagenomic samples, such as a time series.

1. Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA from your environmental samples (e.g., filtered water, soil, gut content).

- Perform whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing using an Illumina platform to generate paired-end short reads (e.g., 2x150 bp). For enhanced results, consider supplementing with long-read data (PacBio or ONT) [18].

- Quality Control: Process raw reads with tools like

Prinseq-liteto quality-trim and remove adapters [18].

2. Metagenomic Co-assembly

- Combine quality-filtered reads from all samples in your time series or experimental set.

- Perform a co-assembly using the metaSPAdes assembler (v3.15.3 or later) with default parameters [16] [18].

- Output: A single set of assembled contigs in FASTA format.

3. Generate Coverage Profiles

- Map the reads from each individual sample back to the co-assembled contigs using a read mapper like Bowtie2 [1] [18].

- Process the resulting SAM/BAM files using

samtoolsto calculate coverage depth for each contig in every sample [18]. - Output: A BAM file for each sample and a summary of coverage information.

4. Metagenomic Binning

- Run the MetaBAT 2 binning algorithm using the co-assembled contigs (FASTA) and the coverage profiles from all samples (BAM files) as input [16] [1] [17].

- Output: Multiple draft genome bins in FASTA format.

5. Bin Refinement and Quality Assessment

- (Optional) Run additional binners like MaxBin and CONCOCT and use DAS Tool to integrate the results into a superior bin set [16].

- Assess the quality of all MAGs using CheckM. Retain only medium and high-quality bins based on the MIMAG standards (completeness > 50%, contamination < 10%) [16] [19].

Table 1: Performance of Assembler-Binner Combinations in Genome Recovery

| Assembler | Binner | Strength in Low-Abundance Recovery | Strength in Strain-Resolved Recovery | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| metaSPAdes | MetaBAT 2 | High [17] | Good | Effective in drinking water & gut metagenomes; produces larger, less fragmented assemblies [16] [17]. |

| MEGAHIT | MetaBAT 2 | Good | High [17] | Excels in recovering strain-resolved genomes; computationally efficient [17]. |

| metaSPAdes | Multiple Binners | Very High | Very High | Leveraging multiple binning approaches recovers unique MAGs that a single workflow would miss [16]. |

Table 2: Impact of Assembly Strategy on Key Metrics

| Assembly Strategy | Contiguity (N50) | Mapping Rate | Sensitivity to Low-Abundance Species | Utility for Strain Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-assembly | Higher [16] | High (e.g., ≥70%) [16] | High [16] [19] | High (via differential coverage) [16] |

| Single-Sample Assembly | Lower [16] | Lower | Lower [16] | Limited (lacks multi-sample coverage data) [16] |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| metaSPAdes | Software (Assembler) | De novo metagenomic assembler. Creates longer, less fragmented contigs from short reads, providing superior input for binning [16] [18]. |

| MetaBAT 2 | Software (Binner) | Metagenomic binning algorithm. Clusters contigs into MAGs using tetranucleotide frequency and differential coverage data; known for accuracy and efficiency [16] [1] [17]. |

| CheckM | Software (Quality Assessment) | Assesses the quality and contamination of MAGs by using lineage-specific marker genes to estimate completeness and contamination [1]. |

| Bowtie2 | Software (Read Mapper) | Aligns short sequencing reads back to a reference (e.g., assembled contigs) to calculate coverage depth for each contig in each sample [1]. |

| DAS Tool | Software (Bin Refinement) | Integrates results from multiple binning tools to generate an optimized, non-redundant set of high-quality MAGs [16]. |

| Illumina Sequencing | Sequencing Technology | Generates high-accuracy short-read data. The standard for achieving high sequencing depth necessary for detecting low-abundance species [18]. |

| PacBio HiFi / ONT | Sequencing Technology | Generates long-read data. Helps resolve complex genomic regions and improves assembly contiguity, which directly benefits binning [18]. |

The Critical Role of Single-Copy Core Genes (SCGs) in Genome Quality Assessment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are Single-Copy Core Genes (SCGs) and why are they fundamental to genome quality assessment? Single-Copy Core Genes (SCGs) are a set of highly conserved, essential genes found in all known life, typically present in only one copy per genome [20]. They are primarily involved in fundamental cellular functions, such as encoding ribosomal proteins and other housekeeping genes [20]. In genome quality assessment, they serve as a benchmark because a complete, uncontaminated genome is expected to contain one, and only one, copy of each universal SCG. The completeness of a genome is estimated by the percentage of a predefined set of SCGs found within it, while contamination is estimated by the number of SCGs that are present in multiple copies [21] [20].

FAQ 2: My genome bin has high completeness but also high contamination. What does this mean and how should I proceed? A bin with high completeness and high contamination, as reported by tools like CheckM, strongly indicates that your Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MAG) likely contains contigs from two or more different organisms [22]. This is a common challenge when binning closely related strains. The high completeness score arises from the combined gene sets of the multiple organisms, while the high redundancy of SCGs reveals the contamination [20]. You should proceed with manual refinement of your MAG using tools like anvi'o, which allows you to visualize differential coverage and sequence composition patterns to separate the interleaved genomes [22].

FAQ 3: Why does my genome bin show low contamination, but I still suspect it might be chimeric? SCG-based analysis is highly effective at detecting redundant contamination (contamination from closely related organisms) but can have lower sensitivity to non-redundant contamination (contamination from unrelated organisms), especially in incomplete genomes [21] [20]. A bin with just 40% completeness has a high probability that contaminating genes will be unique rather than duplicate, leading to an underestimation of contamination [20]. It is recommended to use complementary tools like GUNC, which quantifies lineage homogeneity across the entire gene complement to accurately detect chimerism [21].

FAQ 4: What are the minimum quality thresholds for reporting a MAG, and how do SCGs define them? Community standards, such as the Minimum Information about a Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MIMAG), recommend specific quality tiers based on SCG metrics [21]. The following table summarizes widely accepted quality thresholds for bacterial MAGs:

Table: Standard Quality Tiers for Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs)

| Quality Tier | Completeness | Contamination | Additional Criteria | Suitability for Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality | >90% | <5% | Presence of 5S, 16S, 23S rRNA genes and tRNA genes [21] | Yes; allows for high-confidence analysis. |

| Medium-quality | ≥50% | <10% | - | Often acceptable for publication and downstream analysis. |

| Low-quality | <50% | <10% | - | Use with caution; may be suitable for specific exploratory analyses. |

FAQ 5: Which specific SCGs are considered the most reliable for phylogenomic analysis?

While many large SCG sets exist, recent research has focused on identifying genes with high phylogenetic fidelity—meaning their evolutionary history matches the species' true phylogeny. A set of 20 Validated Bacterial Core Genes (VBCG) has been selected for their high presence, single-copy ratio (>95%), and superior phylogenetic fidelity compared to the 16S rRNA gene tree [23]. This set includes genes like Ribosomal_S2, Ribosomal_S9, PheS, and RpoC [23]. Using a smaller, high-fidelity set can result in more accurate phylogenies with higher resolution at the species and strain level.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inaccurate Strain Resolution in Complex Metagenomes

- Problem Description: Conventional metagenome assembly and binning tools often collapse genetically similar strains into a single, composite MAG, obscuring critical strain-level variations [24] [25].

- Solution: Utilize specialized strain-resolution pipelines.

- For Long-Read Data: Implement Strainberry, an automated pipeline that uses long-read data (PacBio or Nanopore) for de novo strain separation in low-complexity metagenomes. It performs haplotype phasing and read separation to reconstruct strain-specific sequences [24].

- For Multi-Sample Short-Read Data: Use STRONG, a method that performs strain resolution directly on assembly graphs from multiple metagenome samples. It uses a Bayesian algorithm to determine the number of strains and their haplotypes on single-copy core genes [25].

- Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for strain-resolved metagenomic assembly, integrating both short and long-read approaches.

Problem 2: Discrepancies Between Different Binning Tools

- Problem Description: Different binning algorithms (e.g., MetaBAT2, MaxBin2, COMEBin) may produce vastly different bins from the same assembly data, leading to uncertainty in results [5].

- Solution: Employ a consensus and refinement strategy.

- Generate Multiple Binnings: Run several binning tools on your co-assembly.

- Use a Consensus Approach: Leverage tools like

DAS_Toolto integrate results from multiple binners and generate a consolidated, non-redundant set of bins. - Manually Refine Key Bins: For high-priority but questionable MAGs, use an interactive platform like anvi'o for manual refinement. This involves visualizing contigs based on sequence composition (k-mer frequencies) and differential coverage across multiple samples to identify and remove contaminating contigs [22].

Problem 3: Genome Quality Estimates are Unreliable in Low-Completeness Bins

- Problem Description: The standard SCG-based method for estimating completeness and contamination becomes systematically biased for low-completeness genomes (<50%), overestimating completeness and underestimating contamination [20].

- Solution: Interpret SCG metrics with caution for low-completeness bins and use complementary validation.

- Understand the Bias: The bias occurs because in an incomplete genome, a contaminating SCG is likely to be a gene that is missing from the primary genome, so it increases the completeness estimate rather than appearing as a duplicate [20].

- Set Quality Filters: Adhere to the MIMAG standard and prioritize bins that meet at least medium-quality thresholds (≥50% complete, <10% contaminated) for reliable analysis [21].

- Leverage Other Data: If available, use time-series coverage data or methods like emergent self-organizing maps (ESOM) to check the coherence of contigs within a bin [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key software tools and databases essential for genome quality assessment and refinement.

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Genome Quality Assessment and Refinement

| Tool Name | Function | Brief Description of Role |

|---|---|---|

| CheckM | Quality Assessment | Estimates completeness and contamination of genome bins using lineage-specific sets of SCGs [21] [20]. |

| GUNC | Chimera Detection | Detects genome chimerism by quantifying lineage homogeneity of contigs, complementing SCG-based methods [21]. |

| dRep | Genome Dereplication | Groups genomes based on Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI), simplifying analysis by selecting the best-quality representative from redundant sets [21]. |

| anvi'o | Interactive Refinement | An integrated platform for visualization, manual binning, and refinement of MAGs using coverage and sequence composition data [22]. |

| metashot/prok-quality | Automated Quality Pipeline | A comprehensive, containerized Nextflow pipeline that produces MIMAG-compliant quality reports, integrating CheckM, GUNC, and rRNA/tRNA detection [21]. |

| VBCG | Phylogenomic Analysis | A pipeline that uses a validated set of 20 bacterial core genes for high-fidelity phylogenomic analysis [23]. |

The Modern Binning Toolkit: From Deep Learning to Graph-Based Haplotyping

COMEBin (Contrastive Multi-view representation learning for metagenomic Binning) is an advanced binning method that addresses a critical challenge in metagenomic analysis: efficiently grouping DNA fragments (contigs) from the same or closely related genomes without relying on reference databases [5]. This is particularly valuable for discovering novel microorganisms and studying complex microbial communities.

Traditional binning methods face significant difficulties when dealing with closely related strains or efficiently integrating heterogeneous types of information like sequence composition and coverage [5]. COMEBin overcomes these limitations through a contrastive multi-view representation learning framework, which has demonstrated superior performance in recovering high-quality genomes from both simulated and real environmental datasets [5] [26].

Key Concepts: Technical FAQ

Q1: What is contrastive multi-view learning and why is it effective for contig binning?

Contrastive multi-view learning is a self-supervised machine learning technique that learns informative representations by bringing different "views" of the same data instance closer together in an embedding space while pushing apart views of different instances [27]. For COMEBin, this means:

- Multiple Views Generation: COMEBin creates multiple fragments (views) of each contig through data augmentation, generating six different perspectives of each original contig [28].

- Heterogeneous Feature Integration: The method simultaneously leverages two distinct types of features:

- Sequence composition (k-mer distribution)

- Coverage abundance (read coverage across samples) [5]

- Representation Learning: Through contrastive learning, COMEBin obtains high-quality embeddings that effectively integrate these heterogeneous features, making it particularly adept at distinguishing between closely related microbial strains [5].

Q2: What specific advantages does COMEBin offer for researching closely related strains?

COMEBin provides several distinct advantages for studying closely related strains:

- Enhanced Discrimination: The contrastive learning approach learns embeddings that magnify subtle differences between closely related strains, which traditional methods often miss [5].

- Data Augmentation Robustness: By generating multiple views of contigs, COMEBin becomes less sensitive to variations in sequencing depth and contig length [5] [28].

- Heterogeneous Feature Synthesis: The method effectively combines complementary information from k-mer frequencies and coverage profiles, providing a more comprehensive representation for distinguishing similar genomes [5].

Table 1: COMEBin Performance on Challenging Strain-Madness Datasets

| Metric | COMEBin Performance | Second-Best Method | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Near-complete bins recovered | Best overall | Varies by dataset | Up to 22.4% average improvement on real datasets [5] |

| Accuracy (bp) | Highest values | Lower than COMEBin | Consistent superior performance [5] |

| Handling of closely related strains | Most robust | Struggles with high-ANI genomes | Significant advantage in strain discrimination [5] |

Q3: What are the most common installation and dependency issues when implementing COMEBin?

Based on the official implementation, users should be aware of these requirements:

- Operating System: COMEBin v1.0.0 is supported and tested in Linux systems [28].

- Hardware Requirements: Standard computer with sufficient RAM to support in-memory operations [28].

- Dependencies: The implementation requires specific Python environments and dependencies managed through Conda [28].

- CUDA Support: The tool supports GPU acceleration, as evidenced by the

CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES=0flag in execution examples [28].

Troubleshooting Tip: If encountering installation issues, ensure all dependencies are correctly installed using the provided environment configuration files from the official GitHub repository [28].

Q4: How should researchers handle preprocessing and input file generation for COMEBin?

Proper preprocessing is critical for successful COMEBin implementation:

Diagram 1: COMEBin Preprocessing and Input Generation Workflow

Critical Preprocessing Steps:

- Contig Filtering: Keep only contigs longer than 1000bp for binning using the provided

Filter_tooshort.pyscript [28]. - BAM File Generation: Generate alignment files using the modified MetaWRAP script

gen_cov_file.sh[28]. - Coverage Calculation: Properly calculate coverage profiles across all sequencing samples [28].

Common Issue Resolution: If COMEBin fails to recognize input files, verify that BAM files are properly indexed and that contig IDs in the assembly file match those in the alignment files.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Q5: What is the complete experimental workflow for benchmarking COMEBin against other binners?

The comprehensive benchmarking protocol used in the COMEBin study includes:

Diagram 2: COMEBin Benchmarking Experimental Workflow

Key Methodological Details:

- Dataset Diversity: Evaluation includes four CAMI II toy datasets and six benchmark datasets from the second round of CAMI challenges [5].

- Quality Metrics: Use CheckM for assessing genome quality (>90% completeness and <5% contamination defines "near-complete" genomes) [5] [28].

- Comparison Framework: Include both traditional methods (MetaBAT2, MaxBin2, CONCOCT) and deep learning approaches (VAMB, CLMB, SemiBin1, SemiBin2) [5].

Q6: What are the optimal parameters for COMEBin when working with complex microbial communities?

Based on the implementation details, these parameters are critical for performance:

Table 2: Key COMEBin Parameters and Recommended Settings

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Setting | Troubleshooting Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of views (-n) | Views for contrastive learning | Default: 6 [28] | Increase for more complex communities |

| Threads (-t) | Processing threads | Default: 40 [28] | Adjust based on available resources |

| Temperature (-l) | Loss function temperature | 0.07 (N50>10000) or 0.15 (others) [28] | Adjust based on assembly quality |

| Batch size | Training batch size | Default: 1024 [28] | Decrease if memory limited |

| Embedding size | Representation dimension | Default: 2048 [28] | Keep default for optimal performance |

Performance Analysis and Validation

Q7: How significant is COMEBin's performance improvement compared to state-of-the-art methods?

COMEBin demonstrates substantial improvements across multiple metrics and dataset types:

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Comparison of COMEBin vs. Other Methods

| Dataset Type | Performance Metric | COMEBin | Best Alternative | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated Datasets | Near-complete bins recovered | Highest | Second-best method | Average 9.3% [5] |

| Real Environmental Samples | Near-complete bins recovered | Best on 14/16 datasets | Varies by method | Average 22.4% [5] |

| Single-sample Binning | Genome recovery | Superior | Second-best | Average 33.2% [5] |

| Multi-sample Binning | Genome recovery | Superior | Second-best | Average 28.0% [5] |

| PARB Identification | Potential pathogens identified | Highest | MetaBAT2 | 33.3% more [5] |

| BGC Recovery | Moderate+ quality bins with BGCs | Most | Second-best | 126% more (single-sample) [5] |

Q8: What downstream applications benefit most from COMEBin's improved binning?

COMEBin's high-quality binning directly enhances several critical metagenomic applications:

- Pathogen Discovery: Identifies 33.3% more potentially pathogenic antibiotic-resistant bacteria (PARB) compared to MetaBAT2 [5].

- Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Recovery: Recovers 126% more moderate or higher quality bins containing potential biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in single-sample binning compared to the second-best method [5].

- Novel Genome Discovery: Improved recovery of near-complete genomes from real environmental samples, expanding the catalog of microbial diversity [5].

- Strain-Level Analysis: Enhanced capability to distinguish closely related strains, enabling more precise microbial community analysis [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for COMEBin Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CheckM | Assesses genome quality (completeness/contamination) [28] | Essential for validation; requires specific lineage workflows |

| MetaWRAP | Generates BAM files from sequencing reads [28] | Modified scripts provided in COMEBin package |

| Filter_tooshort.py | Filters contigs by length [28] | Minimum 1000bp recommended for binning |

| gencovfile.sh | Generates coverage files from sequencing reads [28] | Supports different read types (paired, single-end, interleaved) |

| Leiden Algorithm | Advanced community detection for clustering [5] | Adapted for binning with single-copy gene information |

| CAMI Datasets | Benchmark datasets for validation [5] | Essential for method comparison and performance verification |

Advanced Technical Support

Q9: How does COMEBin's architecture specifically handle the integration of heterogeneous features?

COMEBin employs a sophisticated neural network architecture specifically designed for heterogeneous data integration:

Diagram 3: COMEBin Neural Network Architecture for Heterogeneous Feature Integration

Architecture Highlights:

- Dual Network Design: Separate "Coverage network" for coverage features and "Combine network" for integrating k-mer features [28].

- Fixed-Dimensional Embeddings: The coverage network ensures consistent embedding dimensions regardless of sample number [5].

- Contrastive Learning Objective: Maximizes agreement between different views of the same contig while discriminating between different contigs [5].

Q10: What validation strategies are recommended when applying COMEBin to novel datasets?

Implement a comprehensive validation protocol:

- Quality Assessment: Use CheckM to evaluate completeness and contamination of recovered genomes [28].

- Benchmark Comparison: Compare against at least two other binning methods (e.g., MetaBAT2 and SemiBin2) as baselines [5].

- Taxonomic Verification: Validate novel bins through taxonomic classification and phylogenetic analysis.

- Functional Validation: Confirm bin quality through identification of complete metabolic pathways or single-copy core genes [5].

Troubleshooting Tip: If bin quality is lower than expected, verify input data quality, particularly assembly N50 statistics, and adjust the temperature parameter (-l) in COMEBin accordingly [28].

Metagenomic binning is a critical computational step that groups DNA fragments (contigs) from the same or closely related microbial genomes after metagenomic assembly. This process is essential for reconstructing Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) and exploring microbial diversity without cultivation. For researchers investigating closely related strains, accurate binning presents particular challenges due to subtle genomic differences that traditional methods often miss. Deep learning approaches, especially variational autoencoders (VAEs) and adversarial autoencoders (AAEs), have significantly advanced the field by learning low-dimensional, informative representations (embeddings) from complex genomic data that improve clustering of closely related strains.

This technical support center addresses practical implementation issues for three advanced binning tools—VAMB, AAMB, and LorBin—which leverage self-supervised and variational autoencoder architectures. These tools have demonstrated superior performance in recovering high-quality genomes, especially from complex microbial communities where strain-level resolution is crucial for understanding microbial function and evolution.

Core Architecture Comparison

Table 1: Architectural Comparison of VAMB, AAMB, and LorBin

| Feature | VAMB | AAMB | LorBin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Adversarial Autoencoder (AAE) with dual latent space | Self-supervised Variational Autoencoder with two-stage clustering |

| Latent Space | Single continuous Gaussian space | Continuous (z) + Categorical (y) spaces | Continuous latent space optimized for long reads |

| Input Features | TNF + abundance profiles | TNF + abundance profiles | TNF + abundance profiles from long-read assemblies |

| Clustering Method | Iterative medoid clustering | Combined clustering from both latent spaces | Multiscale adaptive DBSCAN & BIRCH with assessment-decision model |

| Key Innovation | Integration of features into denoised latent representation | Complementary information from dual latent spaces | Adaptive clustering optimized for imbalanced species distributions |

Performance Characteristics

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across Benchmarking Studies

| Tool | Near-Complete Genomes Recovered | Advantage Over Previous Tools | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAMB | Baseline | Reference-free binning with VAE | Moderate |

| AAMB | ~7% more than VAMB (CAMI2 datasets) | Reconstructs genomes with higher completeness and taxonomic diversity | 1.9x (GPU) to 3.4x (CPU) higher than VAMB |

| LorBin | 15-189% more high-quality MAGs than state-of-the-art binners | Superior for long-read data and identification of novel taxa | 2.3-25.9x faster than SemiBin2 and COMEBin |

Technical Support: Frequently Asked Questions

Installation and Configuration

Q: What are the key dependencies for running AAMB successfully? A: AAMB requires PyTorch with CUDA support for GPU acceleration, in addition to standard bioinformatics dependencies (Python 3.8+, CheckM2 for quality assessment). The significant computational demand (1.9-3.4x higher than VAMB) necessitates adequate GPU memory allocation. For large datasets, we recommend at least 16GB GPU RAM to prevent memory errors during training.

Q: Why does LorBin outperform other tools on long-read metagenomic data? A: LorBin's architecture is specifically designed for long-read assemblies through three key innovations: (1) a self-supervised VAE optimized for hyper-long contigs, (2) a two-stage multiscale adaptive clustering approach using DBSCAN and BIRCH algorithms, and (3) an assessment-decision model for reclustering that improves contig utilization. This makes it particularly effective for handling the continuity and rich information in long-read assemblies, which differ significantly from short-read properties [9].

Runtime Issues and Error Resolution

Q: I encountered "MissingOutputException" when running AVAMB workflow after changing quality thresholds. How can I resolve this?

A: This error often occurs when changing min_comp and max_cont parameters between runs. The issue stems from the workflow's expectation of specific output files that aren't generated when parameters change significantly. Solution: Perform a complete clean run rather than attempting to restart with modified parameters. Delete all intermediate files from previous runs and execute the workflow from scratch with your desired parameters [29].

Q: My AAMB training fails with memory allocation errors, particularly with large datasets. What optimization strategies do you recommend? A: Two effective approaches are: (1) Implement presampling of contigs longer than 10,000 bp before feature extraction to reduce memory footprint without significant information loss; (2) Adjust the batch size parameter to smaller values (64-128) for large datasets (>100GB assembled contigs). Additionally, ensure you're using the latest version that includes memory optimization for the adversarial training process.

Q: How do I interpret and resolve clustering failures in VAMB where related strains are incorrectly binned together?

A: This commonly occurs when the latent space doesn't adequately separate strains with high sequence similarity. First, verify that your input abundance profiles have sufficient variation across samples, as this is crucial for strain separation. Consider increasing the dimensionality of the latent space (adjusting the --dim parameter) from the default 64 to 128 or 256, which provides more capacity to capture subtle strain-level differences. Additionally, ensure your TNF calculation includes reverse complement merging, which improves feature consistency.

Parameter Optimization and Best Practices

Q: What are the recommended quality thresholds for bin refinement when studying closely related strains? A: For strain-level analysis, we recommend stricter thresholds than general microbial profiling: >90% completeness and <5% contamination for high-quality bins, with additional refinement using single-copy marker gene consistency. The AAMB framework has shown particular effectiveness for this purpose, reconstructing genomes with higher completeness and greater taxonomic diversity compared to VAMB [30].

Q: How should I choose between using AAMB's categorical (y) space versus continuous (z) space for specific dataset types? A: Our benchmarking reveals that the optimal latent space is dataset-dependent. AAMB(z) generally outperforms AAMB(y) on most CAMI2 human microbiome datasets (Airways, Gastrointestinal, Oral, Skin, Urogenital), reconstructing 47-102% more near-complete genomes. However, AAMB(y) shows superior performance on the MetaHIT dataset, with 164% more near-complete genomes. For diverse microbial communities, we recommend the default AAMB(z+y) approach, which leverages both spaces and has demonstrated ~7% more near-complete genomes across simulated and real data compared to VAMB [30].

Q: What preprocessing steps are most critical for optimizing LorBin performance with long-read data? A: Three preprocessing steps are essential: (1) Perform rigorous quality trimming and correction of long reads before assembly to minimize embedded errors in contigs; (2) Filter contigs below 2,000 bp before feature extraction to remove fragmented sequences that impair clustering; (3) Normalize coverage across samples using robust scaling methods to ensure abundance profiles accurately reflect biological reality rather than technical artifacts.

Experimental Protocols for Strain-Level Binning

Standardized Workflow for Comparative Benchmarking

Protocol Title: Comparative Evaluation of VAMB, AAMB, and LorBin for Strain-Resolved Binning

Objective: To systematically assess the performance of deep learning-based binners on complex metagenomic datasets containing closely related strains.

Materials:

- Compute Resources: GPU-enabled system (minimum 8GB VRAM) for AAMB and LorBin

- Reference Datasets: CAMI II Challenge datasets (simulated) and MetaHIT (real)

- Quality Assessment Tools: CheckM2 for completeness/contamination evaluation

- Taxonomic Profiling: GTDB-Tk for taxonomic assignment of resulting bins

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Download and preprocess CAMI2 Airways and Gastrointestinal datasets (10 samples each)

- Assembly: Perform co-assembly using MetaSPAdes with standard parameters

- Abundance Profiling: Map reads to contigs using strobealign with

--aembflag - Binning Execution: Run each binner with optimized parameters:

- VAMB: Default parameters with latent dimension 128

- AAMB: Combined z+y latent space approach

- LorBin: Two-stage clustering with adaptive parameters

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate bins using CheckM2 with strict thresholds (>90% completeness, <5% contamination)

- Strain Validation: Assess strain separation using strain-specific marker genes

Expected Results: AAMB should recover approximately 7% more near-complete genomes than VAMB, while LorBin should show particular strength on long-read data with 15-189% more high-quality MAGs compared to state-of-the-art binners [30] [9].

Integration Protocol for Enhanced Recovery

Protocol Title: Ensemble Approach Combining VAMB and AAMB (AVAMB)

Objective: To maximize genome recovery by leveraging complementary strengths of multiple binning approaches.

Procedure:

- Parallel Binning: Execute VAMB and AAMB independently on the same dataset

- Quality Filtering: Remove bins with <70% completeness and >10% contamination using CheckM2

- De-replication: Identify nearly identical bin pairs using Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) >99%

- Contig Assignment: For conflicting contig assignments, assign to the bin whose CheckM2 score improves most

- Validation: Compare the ensemble results against individual binner outputs

Expected Outcome: The integrated pipeline enables improved binning, recovering 20% and 29% more simulated and real near-complete genomes, respectively, compared to VAMB alone, with moderate additional runtime [30].

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Workflow of deep learning-based binning tools showing feature extraction, latent space representation, and clustering approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Computational Research Reagents for Deep Learning-Based Binning

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CheckM2 | Assesses bin quality (completeness/contamination) | Essential for evaluating output from all binning tools |

| GTDB-Tk | Taxonomic classification of MAGs | Critical for determining novelty of binned genomes |

| MetaSPAdes | Metagenomic assembly | Generates contigs for subsequent binning |

| Strobealign | Read mapping with --aemb flag |

Generates abundance profiles for binning |

| CAMI datasets | Benchmarking standards | Validating tool performance on known communities |

| dRep | Genome de-replication | Removes redundant genomes from multiple binning runs |

| ProxiMeta Hi-C | Chromatin conformation capture | Provides long-range information for binning (metaBAT-LR) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of the Leiden algorithm over the Louvain algorithm for contig binning?

The Leiden algorithm addresses a key limitation of the Louvain algorithm by guaranteeing well-connected communities. While the Louvain algorithm can sometimes yield partitions where communities are poorly connected, the Leiden algorithm systematically refines partitions by periodically subdividing communities into smaller, well-connected groups. This improvement is crucial for contig binning, as it leads to more biologically plausible genome bins, especially for complex metagenomes containing closely related strains. Furthermore, the Leiden algorithm often achieves higher modularity in less time compared to Louvain [31] [32].

Q2: My DBSCAN algorithm returns a single large cluster containing all my contigs. How can I fix this?

This typically occurs when the eps parameter is set too high, causing distinct dense regions to merge into one. We recommend the following troubleshooting steps:

- Re-evaluate the eps value: Use the k-distance graph method to determine a more appropriate

epsvalue. Plot the distance to the k-th nearest neighbor for all data points and look for the "elbow" point, which is a good candidate foreps. - Adjust MinPts: Increase the

min_samplesparameter. A general rule of thumb is to setMinPtsto be greater than or equal to the number of dimensions in your dataset plus one [33]. - Data Preprocessing: Ensure your feature data (e.g., k-mer frequencies and coverage profiles) is properly normalized. Variables with larger scales can dominate the distance calculation, so standardization is often necessary [34].

Q3: How does the BIRCH algorithm handle the large memory requirements of very large metagenomic datasets?

BIRCH (Balanced Iterative Reducing and Clustering using Hierarchies) is specifically designed for this scenario. It does not cluster the entire large dataset directly. Instead, it first generates a compact, in-memory summary of the large dataset called a Clustering Feature (CF) Tree. This tree retains the essential information about the data's distribution as a set of CF triplets (N, LS, SS), representing the number of data points, their linear sum, and their squared sum, respectively. The actual clustering is then performed on this much smaller CF Tree summary, drastically reducing memory consumption and processing time [35] [36].

Q4: How can I control the number and size of clusters generated by the Leiden algorithm?

The Leiden algorithm features a resolution parameter that directly controls the granularity of the clustering. A higher resolution parameter leads to a larger number of finer, smaller clusters, while a lower resolution results in fewer, larger clusters [32]. For example, in single-cell RNA-seq analysis, it is common practice to run the algorithm multiple times with different resolution values (e.g., 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0) to explore the clustering structure at different scales. Some implementations also allow you to set a maximum community size max_comm_size to explicitly constrain cluster growth [37].

Q5: Which clustering algorithm is best for recovering near-complete genomes from a dataset with many closely related strains?

This is a challenging task. The COMEBin method, which is based on contrastive multi-view representation learning and uses the Leiden algorithm for the final clustering step, has been demonstrated to outperform other state-of-the-art binning methods in this context. It shows a significant improvement in recovering near-complete genomes (>90% completeness and <5% contamination) from real environmental samples that contain closely related strains [5]. Its data augmentation and specialized coverage module make it particularly robust.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Leiden Algorithm Community Detection

Problem: The algorithm is not converging or produces different results in each run.

- Cause 1: The Leiden algorithm is inherently non-deterministic, meaning it can generate different communities in subsequent runs due to its random elements [31].

- Solution: To ensure reproducible results, set a random seed for the underlying code (if the implementation allows it). Furthermore, you can tweak the

thetaparameter, which controls the randomness when breaking a community into smaller parts. A lowerthetareduces randomness [31]. - Cause 2: The number of iterations may be insufficient.

- Solution: Increase the

max_iterationsparameter. You can set it to a very high number to allow the algorithm to run until convergence is reached [31].

Problem: All nodes merge into a single community or each node forms its own community.

- Cause: An ill-suited value for the

gamma(resolution) parameter [31]. - Solution: Adjust the

gammaparameter. A highergammavalue encourages the formation of more, smaller communities. Systematically test a range of values (e.g., from 0.1 to 3.0) to find the optimal resolution for your specific dataset [31] [32].

Troubleshooting DBSCAN Clustering

Problem: Most data points are labeled as noise (-1).

- Cause 1: The

epsvalue is too small. The neighborhood radius is insufficient to capture the local density of your clusters [33]. - Solution: Increase the

epsvalue. Use the k-distance graph to guide your selection. - Cause 2: The

min_samplesvalue is too high. - Solution: Decrease the